По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

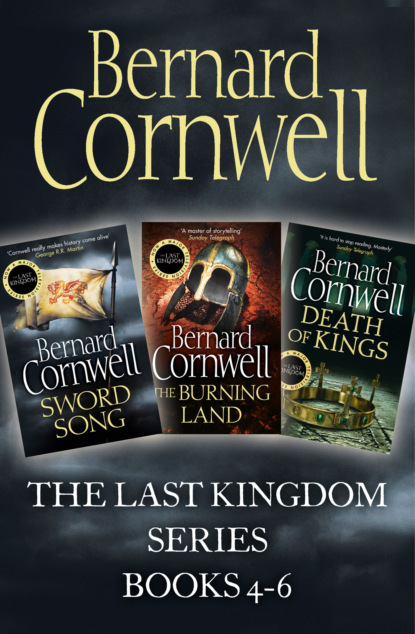

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I want two apologies,’ I said.

He heard the menace in my voice and turned back to me, alarmed now. ‘This house,’ Aldhelm explained, ‘belongs to the Lord Æthelred. If you live here it is by his gracious permission.’ He became even more alarmed as I drew closer. ‘Egbert!’ he said loudly, but Egbert’s only response was a calming motion with his right hand, a signal that his men should keep their swords scabbarded. Egbert knew that if a single blade left its long scabbard there would be a fight between his men and mine, and he had the sense to avoid that slaughter, but Aldhelm had no such sense. ‘You impertinent bastard,’ he said, and snatched a knife from a sheath at his waist and lunged it at my belly.

I broke Aldhelm’s jaw, his nose, both his hands and maybe a couple of his ribs before Egbert hauled me away. When Aldhelm apologised to Gisela he did so while spitting teeth through bubbling blood, and the urn stayed in our courtyard. I gave his knife to the girls who worked in the kitchen, where it proved useful for cutting onions.

And the next day, Alfred came.

The king came silently, his ship arriving at a wharf upstream of the broken bridge. The Haligast waited for a river trader to pull away, then ghosted in on short, efficient oar strokes. Alfred, accompanied by a score of priests and monks, and guarded by six mailed men, came ashore unheralded and unannounced. He threaded the goods stacked on the wharf, stepped over a drunken man sleeping in the shade and ducked through the small gate in the wall leading to a merchant’s courtyard.

I heard he went to the palace. Æthelred was not there, he was hunting again, but the king went to his daughter’s chamber and stayed there a long time. Afterwards he walked back down the hill and, still with his priestly entourage, came to our house. I was with one of the groups making repairs to the walls, but Gisela had been warned of Alfred’s presence in Lundene and, suspecting he might come to our house, had prepared a meal of bread, ale, cheese and boiled lentils. She offered no meat, for Alfred would not touch flesh. His stomach was tender and his bowels in perpetual torment and he had somehow persuaded himself that meat was an abomination.

Gisela had sent a servant to warn me of the king’s arrival, yet even so I arrived at the house long after Alfred to find my elegant courtyard black with priests, among whom was Father Pyrlig and, next to him, Osferth, who was once again dressed in monkish robes. Osferth gave me a sour look, as if blaming me for his return to the church, while Pyrlig embraced me. ‘Æthelred said nothing of you in his report to the king,’ he murmured those words, gusting ale-smelling breath over my face.

‘We weren’t here when the city fell?’ I asked.

‘Not according to your cousin,’ Pyrlig said, then chuckled. ‘But I told Alfred the truth. Go on, he’s waiting for you.’

Alfred was on the river terrace. His guards stood behind him, lined against the house, while the king was seated on a wooden chair. I paused in the doorway, surprised because Alfred’s face, usually so pallid and solemn, had an animated look. He was even smiling. Gisela was seated next to him and the king was leaning forward, talking, and Gisela, whose back was to me, was listening. I stayed where I was, watching that rarest of sights, Alfred happy. He tapped a long white finger on her knee once to stress some point. There was nothing untoward in the gesture, except it was so unlike him.

But then, of course, maybe it was very like him. Alfred had been a famous womaniser before he was caught in the snare of Christianity, and Osferth was a product of that early princely lust. Alfred liked pretty women, and it was obvious he liked Gisela. I heard her laugh suddenly and Alfred, flattered by her amusement, smiled shyly. He seemed not to mind that she was no Christian and that she wore a pagan amulet about her neck, he was simply happy to be in her company and I was tempted to leave them alone. I had never seen him happy in the company of Ælswith, his weasel-tongued, stoat-faced, shrike-voiced wife. Then he happened to glance over Gisela’s shoulder and saw me.

His face changed immediately. He stiffened, sat upright and reluctantly beckoned me forward.

I picked up a stool that our daughter used and heard a hiss as Alfred’s guards drew swords. Alfred waved the blades down, sensible enough to know that if I had wanted to attack him then I would hardly use a three-legged milking stool. He watched as I gave my swords to one of the guards, a mark of respect, then as I carried the stool across the terrace flagstones. ‘Lord Uhtred,’ he greeted me coldly.

‘Welcome to our house, lord King.’ I gave him a bow, then sat with my back to the river.

He was silent for a moment. He was wearing a brown cloak that was drawn tight around his thin body. A silver cross hung at his neck, while on his thinning hair was a circlet of bronze, which surprised me, for he rarely wore symbols of kingship, thinking them vain baubles, but he must have decided that Lundene needed to see a king. He sensed my surprise for he clawed the circlet off his head. ‘I had hoped,’ he said coldly, ‘that the Saxons of the new town would have abandoned their houses. That they would live here instead. They could be protected here by the walls! Why won’t they move?’

‘They fear the ghosts, lord,’ I said.

‘And you do not?’

I thought for a while. ‘Yes,’ I said after thinking about my answer.

‘Yet you live here?’ he waved at the house.

‘We propitiate the spirits, lord,’ Gisela explained softly and, when the king raised an eyebrow, she told how we placed food and drink in the courtyard to greet any ghosts who came to our house.

Alfred rubbed his eyes. ‘It might be better,’ he said, ‘if our priests exorcise the streets. Prayer and holy water! We shall drive the ghosts away.’

‘Or let me take three hundred men to sack the new town,’ I suggested. ‘Burn their houses, lord, and they’ll have to live in the old city.’

A half-smile flickered on his face, gone as quickly as it had showed. ‘It is hard to force obedience,’ he said, ‘without encouraging resentment. I sometimes think the only true authority I have is over my family, and even then I wonder! If I release you with sword and spear onto the new town, Lord Uhtred, then they will learn to hate you. Lundene must be obedient, but it must also be a bastion of Christian Saxons, and if they hate us then they will welcome a return of the Danes, who left them in peace.’ He shook his head abruptly. ‘We shall leave them in peace, but don’t build them a palisade. Let them come into the old city of their own accord. Now, forgive me,’ those last two words were to Gisela, ‘but we must speak of still darker things.’

Alfred gestured to a guard who pushed open the door from the terrace. Father Beocca appeared and with him a second priest; a black-haired, pouchy-faced, scowling creature called Father Erkenwald. He hated me. He had once tried to have me killed by accusing me of piracy and, though his accusations had been entirely true, I had slipped away from his bad-tempered clutches. He gave me a sour look while Beocca offered a solemn nod, then both men stared attentively at Alfred.

‘Tell me,’ Alfred said, looking at me, ‘what Sigefrid, Haesten and Erik do now?’

‘They’re at Beamfleot, lord,’ I said, ‘strengthening their camp. They have thirty-two ships, and men enough to crew them.’

‘You’ve seen this place?’ Father Erkenwald demanded. The two priests, I knew, had been fetched onto the terrace to serve as witnesses to this conversation. Alfred, ever careful, liked to have a record, either written or memorised, of all such discussions.

‘I’ve not seen it,’ I said coldly.

‘Your spies, then?’ Alfred resumed the questions.

‘Yes, lord.’

He thought for a moment. ‘The ships can be burned?’ he asked.

I shook my head. ‘They’re in a creek, lord.’

‘They must be destroyed,’ he said vengefully, and I saw his long thin hands clench on his lap. ‘They raided Contwaraburg!’ he said, sounding distraught.

‘I heard of it, lord.’

‘They burned the church!’ he said indignantly, ‘and stole everything! Gospel books, crosses, even the relics!’ he shuddered. ‘The church possessed a leaf of the fig tree that our Lord Jesus withered! I touched it once, and felt its power.’ He shuddered again. ‘It is all gone to pagan hands.’ He sounded as if he might weep.

I said nothing. Beocca had started writing, his pen scratching on a parchment held awkwardly in his lamed hand. Father Erkenwald was holding a pot of ink and had a look of disdain as if such a chore was belittling him. ‘Thirty-two ships, did you say?’ Beocca asked me.

‘That was the last I heard.’

‘Creeks can be entered,’ Alfred said acidly, his distress suddenly gone.

‘The creek at Beamfleot dries at low tide, lord,’ I explained, ‘and to reach the enemy ships we must pass their camp, which is on a hill above the mooring. And the last report I received, lord, said a ship was permanently moored across the channel. We could destroy that ship and fight our way through, but you’ll need a thousand men to do it and you’ll lose at least two hundred of them.’

‘A thousand?’ he asked sceptically.

‘The last I heard, lord, said Sigefrid had close to two thousand men.’

He closed his eyes briefly. ‘Sigefrid lives?’

‘Barely,’ I said. I had received most of this news from Ulf, my Danish trader, who loved the silver I paid him. I had no doubt Ulf was receiving silver from Haesten or Erik for telling them what I did in Lundene, but that was a price worth paying. ‘Brother Osferth wounded him badly,’ I said.

The king’s shrewd eyes rested on me. ‘Osferth,’ he said tonelessly.

‘Won the battle, lord,’ I said just as tonelessly. Alfred just watched me, still expressionless. ‘You heard from Father Pyrlig?’ I asked, and received a curt nod. ‘What Osferth did, lord, was brave,’ I said, ‘and I am not certain I would have had the courage to do it. He jumped from a great height and attacked a fearsome warrior, and he lived to remember the achievement. If it was not for Osferth, lord, Sigefrid would be in Lundene today and I would be in my grave.’

‘You want him back?’ Alfred asked.

The answer, of course, was no, but Beocca gave an almost imperceptible nod of his grey head and I understood Osferth was not wanted in Wintanceaster. I did not like the youth and, judging from Beocca’s silent message, no one liked him in Wintanceaster either, yet his courage had been exemplary. Osferth was, I thought, a warrior at heart. ‘Yes, lord,’ I said, and saw Gisela’s secret smile.

‘He’s yours,’ Alfred said shortly. Beocca rolled his good eye to heaven in gratitude. ‘And I want the Northmen out of the Temes estuary,’ Alfred went on.

I shrugged. ‘Isn’t that Guthrum’s business?’ I asked. Beamfleot lay in the kingdom of East Anglia with which, officially, we were at peace.

Alfred looked irritated, probably because I had used Guthrum’s Danish name. ‘King Æthelstan has been informed of the problem,’ he said.