По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

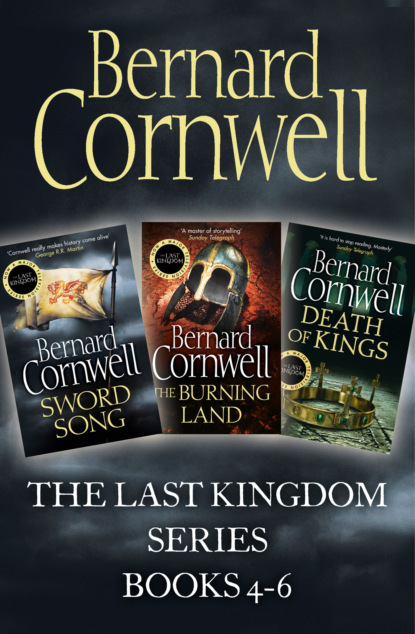

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Of course,’ Æthelred agreed quickly. I noted that many of the thegns looked dubious.

Alfred saw it too and glanced at me. ‘This is your responsibility, Lord Uhtred. Have you no opinion?’

I almost yawned, but managed to resist the impulse. ‘I have better than an opinion, lord King,’ I said, ‘I can give you fact.’

Alfred raised an eyebrow and managed to look disapproving at the same time. ‘Well?’ he asked irritably when I paused too long.

‘Four men for every pole,’ I said. A pole was six paces, or thereabouts, and the allocation of four men to a pole was not mine, but Alfred’s. When he ordered the burhs built he had worked out in his meticulous way how many men would be needed to defend each, and the distance about the walls determined the final figure. Coccham’s walls were one thousand four hundred paces in length and so my household guards and the fyrd had to supply a thousand men for its defence. But Coccham was a small burh, Lundene a city.

‘And the distance about Lundene’s walls?’ Alfred demanded.

I looked at Æthelred, as though expecting him to answer and Alfred, seeing where I looked, also gazed at his son-in-law. Æthelred thought for a heartbeat and, instead of telling the truth which was that he did not know, made a guess. ‘Eight hundred poles, lord King?’

‘The landward wall,’ I broke in harshly, ‘is six hundred and ninety-two poles. The river wall adds a further three hundred and fifty-eight. The defences, lord King, stretch for one thousand and fifty poles.’

‘Four thousand, two hundred men,’ Bishop Erkenwald said immediately, and I confess I was impressed. It had taken me a long time to discover that number, and I had not been certain my computation had been correct until Gisela also worked the problem out.

‘No enemy, lord King,’ I said, ‘can attack everywhere at once, so I reckon the city can be defended by a garrison of three thousand, four hundred men.’

One of the Mercian thegns made a hissing noise, as though such a figure was an impossibility. ‘Only one thousand men more than your garrison in Wintanceaster, lord King,’ I pointed out. The difference, of course, was that Wintanceaster lay in a loyal West Saxon shire that was accustomed to its men serving their turn in the fyrd.

‘And where do you find those men?’ a Mercian demanded.

‘From you,’ I said harshly.

‘But …’ the man began, then faltered. He was going to point out that the Mercian fyrd was a useless thing, grown weak by disuse, and that any attempt to raise the fyrd might draw the malevolent attention of the Danish earls who ruled in northern Mercia, and so these men had learned to lie low and keep silent. They were like deerhounds who shiver in the undergrowth for fear of attracting the wolves.

‘But nothing,’ I said, louder and harsher still. ‘For if a man does not contribute to his country’s defence then that man is a traitor. He should be dispossessed of his land, put to death, and his family reduced to slavery.’

I thought Alfred might object to those words, but he kept silent. Indeed, he nodded agreement. I was the blade inside his scabbard and he was evidently pleased that I had shown the steel for an instant. The Mercians said nothing.

‘We also need men for ships, lord King,’ I went on.

‘Ships?’ Alfred asked.

‘Ships?’ Erkenwald echoed.

‘We need crewmen,’ I explained. We had captured twenty-one ships when we took Lundene, of which seventeen were fighting boats. The others were wider beamed, built for trading, but they could be useful too. ‘I have the ships,’ I went on, ‘but they need crews, and those crews have to be good fighters.’

‘You defend the city with ships?’ Erkenwald asked defiantly.

‘And where will your money come from?’ I asked him. ‘From customs dues. But no trader dare sail here, so I have to clear the estuary of enemy ships. That means killing the pirates, and for that I need crews of fighting men. I can use my household troops, but they have to be replaced in the city’s garrison by other men.’

‘I need ships,’ Æthelred suddenly intervened.

Æthelred needed ships? I was so astonished that I said nothing. My cousin’s job was to defend southern Mercia and push the Danes northwards from the rest of his country, and that would mean fighting on land. Now, suddenly, he needed ships? What did he plan? To row across pastureland?

‘I would suggest, lord King,’ Æthelred was smiling as he spoke, his voice smooth and respectful, ‘that all the ships west of the bridge be given to me, for use in your service,’ and he bowed to Alfred when he said that, ‘and my cousin be given the ships east of the bridge.’

‘That …’ I began, but was cut off by Alfred.

‘That is fair,’ the king said firmly. It was not fair, it was ridiculous. There were only two fighting ships in the stretch of river east of the bridge, and fifteen upstream of the obstruction. The presence of those fifteen ships suggested that Sigefrid had been planning a major raid on Alfred’s territory before we struck him, and I needed those ships to scour the estuary clear of enemies. But Alfred, eager to be seen supporting his son-in-law, swept my objections aside. ‘You will use what ships you have, Lord Uhtred,’ he insisted, ‘and I will put seventy of my household guard under your command to crew one ship.’

So I was to drive the Danes from the estuary with two ships? I gave up, and leaned against the wall as the discussion droned on, mostly about the level of customs to be charged, and how much the neighbouring shires were to be taxed, and I wondered yet again why I was not in the north where a man’s sword was free and there was small law and much laughter.

Bishop Erkenwald cornered me when the meeting was over. I was strapping on my sword belt when he peered up at me with his beady eyes. ‘You should know,’ he greeted me, ‘that I opposed your appointment.’

‘As I would have opposed yours,’ I said bitterly, still angry at Æthelred’s theft of the fifteen warships.

‘God may not look with blessing on a pagan warrior,’ the newly appointed bishop explained himself, ‘but the king, in his wisdom, considers you a soldier of ability.’

‘And Alfred’s wisdom is famous,’ I said blandly.

‘I have spoken with the Lord Æthelred,’ he went on, ignoring my words, ‘and he has agreed that I can issue writs of assembly for Lundene’s adjacent counties. You have no objection?’

Erkenwald meant that he now had the power to raise the fyrd. It was a power that might better have been given me, but I doubted Æthelred would have agreed to that. Nor did I think that Erkenwald, nasty man though he was, would be anything but loyal to Alfred. ‘I have no objection,’ I said.

‘Then I shall inform Lord Æthelred of your agreement,’ he said formally.

‘And when you speak with him,’ I said, ‘tell him to stop hitting his wife.’

Erkenwald jerked as though I had just struck him in the face. ‘It is his Christian duty,’ he said stiffly, ‘to discipline his wife, and it is her duty to submit. Did you not listen to what I preached?’

‘To every word,’ I said.

‘She brought it on herself,’ Erkenwald snarled. ‘She has a fiery spirit, she defies him!’

‘She’s little more than a child,’ I said, ‘and a pregnant child at that.’

‘And foolishness is deep in the heart of a child,’ Erkenwald responded, ‘and those are the words of God! And what does God say should be done about the foolishness of a child? That the rod of correction shall beat it far away!’ He shuddered suddenly. ‘That is what you do, Lord Uhtred! You beat a child into obedience! A child learns by suffering pain, by being beaten, and that pregnant child must learn her duty. God wills it! Praise God!’

I heard only last week that they want to make Erkenwald into a saint. Priests come to my home beside the northern sea where they find an old man, and they tell me I am just a few paces from the fires of hell. I only need repent, they say, and I will go to heaven and live for evermore in the blessed company of the saints.

And I would rather burn till time itself burns out.

Seven (#ulink_876fd630-445c-575b-aa29-5a609761cb58)

Water dripped from oar-blades, the drips spreading ripples in a sea that was shining slabs of light that slowly shifted and parted, joined and slid.

Our ship was poised on that shifting light, silent.

The sky to the east was molten gold pouring around a bank of sun-drenched cloud, while the rest was blue. Pale blue to the east and dark blue to the west where night fled towards the unknown lands beyond the distant ocean.

To the south I could see the low shore of Wessex. It was green and brown, treeless and not that far away, though I would go no closer for the light-sliding sea concealed mudbanks and shoals. Our oars were resting and the wind was dead, but we moved relentlessly eastwards, carried by the tide and by the river’s strong flow. This was the estuary of the Temes; a wide place of water, mud, sand and terror.

Our ship had no name and she carried no beast-heads on her prow or stern. She was a trading ship, one of the two I had captured in Lundene, and she was wide-beamed, sluggish, big-bellied and clumsy. She carried a sail, but the sail was furled on the yard, and the yard was in its crutches. We drifted on the tide towards the golden dawn.

I stood with the steering-oar in my right hand. I wore mail, but no helmet. My two swords were strapped to my waist, but they, like my mail coat, were hidden beneath a dirty brown woollen cloak. There were twelve rowers on the benches, Sihtric was beside me, one man was on the bow platform and all those men, like me, showed neither armour nor weapons.