По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

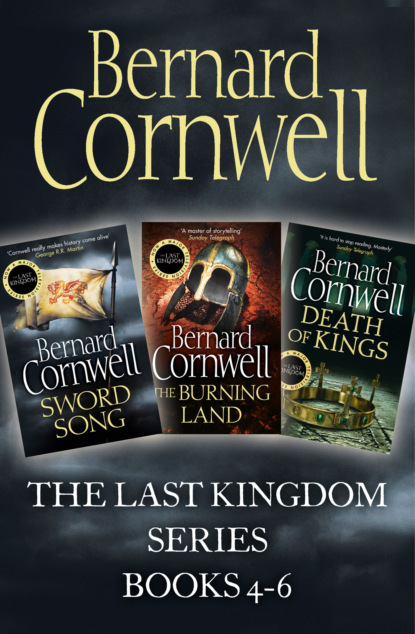

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I dare do more than that, bishop,’ I said. ‘You’ve heard of Brother Jænberht? One of your precious martyrs? I killed him in a church and your god neither saved him nor stopped my blade.’ I smiled, remembering my own astonishment as I had cut Jænberht’s throat. I had hated that monk. ‘Your king,’ I said to Erkenwald, ‘wants his god’s work done, and that work is killing Danes, not amusing yourself by looking at a young girl’s nakedness.’

‘This is God’s work!’ Æthelred shouted at me.

I wanted to kill him then. I felt the twitch as my hand went to Serpent-Breath’s hilt, but just then the hag came back. ‘She’s …’ the woman started, then fell silent as she saw the look of hatred I was giving Æthelred.

‘Speak, woman!’ Erkenwald commanded.

‘She shows no signs, lord,’ the woman said grudgingly. ‘Her skin is unmarked.’

‘Belly and thighs?’ Erkenwald pressed the woman.

‘She is pure,’ Gisela spoke from a recess at the side of the church. She had an arm around Æthelflaed and her voice was bitter.

Erkenwald seemed discomfited by the report, but drew himself up and grudgingly acknowledged that Æthelflaed was indeed pure. ‘She is evidently undefiled, lord,’ he said to Æthelred, pointedly ignoring me. Finan was standing behind the watching priests, his presence a threat to them. The Irishman was smiling and watching Aldhelm who, like Æthelred, wore a sword. Either man could have tried to cut me down, but neither touched their weapon.

‘Your wife,’ I said to Æthelred, ‘is not undefiled. She’s defiled by you.’

His face jerked up as though I had slapped him. ‘You are …’ he began.

I unleashed the anger then. I was much taller and broader than my cousin, and I bullied him back from the altar to the side wall of the church, and there I spoke to him in a hiss of fury. Only he could hear what I said. Aldhelm might have been tempted to rescue Æthelred, but Finan was watching him, and the Irishman’s reputation was enough to ensure that Aldhelm did not move. ‘I have known Æthelflaed since she was a small child,’ I told Æthelred, ‘and I love her as if she was my own child. Do you understand that, earsling? She is like a daughter to me, and she is a good wife to you. And if you touch her again, cousin, if I see one more bruise on Æthelflaed’s face, I shall find you and I shall kill you.’ I paused, and he was silent.

I turned and looked at Erkenwald. ‘And what would you have done, bishop,’ I sneered, ‘if the Lady Æthelflaed’s thighs had rotted? Would you have dared kill Alfred’s daughter?’

Erkenwald muttered something about condemning her to a nunnery, not that I cared. I had stopped close beside Aldhelm and looked at him. ‘And you,’ I said, ‘struck a king’s daughter.’ I hit him so hard that he spun into the altar and staggered for balance. I waited, giving him a chance to fight back, but he had no courage left so I hit him again and then stepped away and raised my voice so that everyone in the church could hear. ‘And the King of Wessex orders the Lord Æthelred to set sail.’

Alfred had sent no such orders, but Æthelred would hardly dare ask his father-in-law whether he had or not. As for Erkenwald, I was sure he would tell Alfred that I had carried a sword and made threats inside a church, and Alfred would be angry at that. He would be more angry with me for defiling a church than he would be with the priests for humiliating his daughter, but I wanted Alfred to be angry. I wanted him to punish me by dismissing me from my oath and thus releasing me from his service. I wanted Alfred to make me a free man again, a man with a sword, a shield and enemies. I wanted to be rid of Alfred, but Alfred was far too clever to allow that. He knew just how to punish me.

He would make me keep my oath.

It was two days later, long after Gunnkel had fled from Hrofeceastre, that Æthelred at last sailed. His fleet of fifteen warships, the most powerful fleet Wessex had ever assembled, slid downriver on the ebb tide, propelled by an angry message that was delivered to Æthelred by Steapa. The big man had ridden from Hrofeceastre, and the message he carried from Alfred demanded to know why the fleet lingered while the defeated Vikings fled. Steapa stayed that night at our house. ‘The king is unhappy,’ he told me over supper, ‘I’ve never seen him so angry!’ Gisela was fascinated by the sight of Steapa eating. He was using one hand to hold pork ribs that he flensed with his teeth, while the other fed bread into a spare corner of his mouth. ‘Very angry,’ he said, pausing to drink ale. ‘The Sture,’ he added mysteriously, picking up a new slab of ribs.

‘The Sture?’

‘Gunnkel made a camp there, and Alfred thinks he’s probably gone back to it.’

The Sture was a river in East Anglia, north of the Temes. I had been there once and remembered a wide mouth protected from easterly gales by a long spit of sandy land. ‘He’s safe there,’ I said.

‘Safe?’ Steapa asked.

‘Guthrum’s territory.’

Steapa paused to pull a scrap of meat from between his teeth. ‘Guthrum sheltered him there. Alfred doesn’t like it. Thinks Guthrum has to be smacked.’

‘Alfred’s going to war with East Anglia?’ Gisela asked, surprised.

‘No, lady. Just smacking him,’ Steapa said, crunching his jaws on some crackling. I reckoned he had eaten half a pig and showed no signs of slowing down. ‘Guthrum doesn’t want war, lady. But he has to be taught not to shelter pagans. So he’s sending the Lord Æthelred to attack Gunnkel’s camp on the Sture, and while he’s at it to steal some of Guthrum’s cattle. Just smack him.’ Steapa gave me a solemn look. ‘Pity you can’t come.’

‘It is,’ I agreed.

And why, I wondered, had Alfred chosen Æthelred to lead an expedition to punish Guthrum? Æthelred was not even a West Saxon, though he had sworn an oath to Alfred of Wessex. My cousin was a Mercian, and the Mercians have never been famous for their ships. So why choose Æthelred? The only explanation I could find was that Alfred’s eldest son, Edward, was still a child with an unbroken voice and Alfred himself was a sick man. He feared his own death, and he feared the chaos that could descend on Wessex if Edward took the throne as a child. So Alfred was offering Æthelred a chance to redeem himself for his failure to trap Gunnkel’s ships in the Medwæg, and an opportunity to make himself a reputation large enough to persuade the thegns and ealdormen of Wessex that Æthelred, Lord of Mercia, could rule them if Alfred died before Edward was old enough to succeed.

Æthelred’s fleet carried a message to the Danes of East Anglia. If you raid Wessex, Alfred was saying, then we shall raid you. We shall harry your coast, burn your houses, sink your ships and leave your beaches stinking of death. Alfred had made Æthelred into a Viking, and I was jealous. I wanted to take my ships, but I had been ordered to stay in Lundene, and I obeyed. Instead I watched the great fleet leave Lundene. It was impressive. The largest of the captured warships had thirty oars a side, and there were six of those, while the smallest had banks of twenty. Æthelred was leading almost a thousand men on his raid, and they were all good men; warriors from Alfred’s household and from his own trained troops. Æthelred sailed in one of the large ships that had once carried a great raven’s head, scorched black, on her stem, but that beaked image was gone and now the ship was named Rodbora, which meant ‘carrier of the cross’, and her stem-post was now decorated with a massive cross and she sailed with warriors aboard, and with priests, and, of course, with Æthelflaed, for Æthelred would go nowhere without her.

It was summer. Folk who have never lived in a town during the summer cannot imagine the stench of it, nor the flies. Red kites flocked in the streets, living off carrion. When the wind was north the smell of the urine and animal dung in the tanners’ pits mixed with the city’s own stench of human sewage. Gisela’s belly grew, and my fear for her grew with it.

I went to sea as often as I could. We took Sea-Eagle and Sword of the Lord down the river on the ebb tide and came back with the flood. We hunted ships from Beamfleot, but Sigefrid’s men had learned their lesson and they never left their creek with fewer than three ships in company. Yet, though those groups of ships hunted prey, trade was at last reaching Lundene, for the merchants had learned to sail in large convoys. A dozen ships would keep each other company, all with armed men aboard and so Sigefrid’s pickings were scanty, but so were mine.

I waited two weeks for news of my cousin’s expedition, and learned its fate on a day when I made my usual excursion down the Temes. There was always a blessed moment as we left the smoke and smells of Lundene and felt the clean sea winds. The river looped about wide marshes where herons stalked. I remember being happy that day because there were blue butterflies everywhere. They settled on the Sea-Eagle and on the Sword of the Lord that followed in our wake. One insect perched on my outstretched finger where it opened and closed its wings.

‘That means good luck, lord,’ Sihtric said.

‘It does?’

‘The longer it stays there, the longer your luck lasts,’ Sihtric said, and held out his own hand, but no blue butterfly settled there.

‘Looks like you’ve no luck,’ I said lightly. I watched the butterfly on my finger and thought of Gisela and of childbirth. Stay there, I silently ordered the insect, and it did.

‘I’m lucky, lord,’ Sihtric said, grinning.

‘You are?’

‘Ealhswith’s in Lundene,’ he said. Ealhswith was the whore whom Sihtric loved.

‘There’s more trade for her in Lundene than in Coccham,’ I said.

‘She stopped doing that,’ Sihtric said fiercely.

I looked at him, surprised. ‘She has?’

‘Yes, lord. She wants to marry me, lord.’

He was a good-looking young man, hawk-faced, black-haired and well built. I had known him since he was almost a child, and I supposed that altered my impression of him, for I still saw the frightened boy whose life I had spared in Cair Ligualid. Ealhswith, perhaps, saw the young man he had become. I looked away, watching a tiny trickle of smoke rising from the southern marshes and I wondered whose fire it was and how they lived in that mosquito-haunted swamp. ‘You’ve been with her a long time,’ I said.

‘Yes, lord.’

‘Send her to me,’ I said. Sihtric was sworn to me and he needed my permission to marry because his wife would become a part of my household and thus my responsibility. ‘I’ll talk to her,’ I added.

‘You’ll like her, lord.’

I smiled at that. ‘I hope so,’ I said.

A flight of swans beat between our boats, their wings loud in the summer air. I was feeling content, all but for my fears about Gisela, and the butterfly was allaying that worry, though after a while it launched itself from my finger and fluttered clumsily in the southwards wake of the swans. I touched Serpent-Breath’s hilt, then my amulet, and sent a prayer to Frigg that Gisela would be safe.

It was midday before we were abreast of Caninga. The tide was low and the mudflats stretched into the calm estuary where we were the only ships. I took Sea-Eagle close to Caninga’s southern shore and stared towards Beamfleot’s creek, but I could see nothing useful through the heat haze that shimmered above the island. ‘Looks like they’ve gone,’ Finan commented. Like me he was staring northwards.

‘No,’ I said, ‘there are ships there.’ I thought I could see the masts of Sigefrid’s ships through the wavering air.

‘Not as many as there should be,’ Finan said.