По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

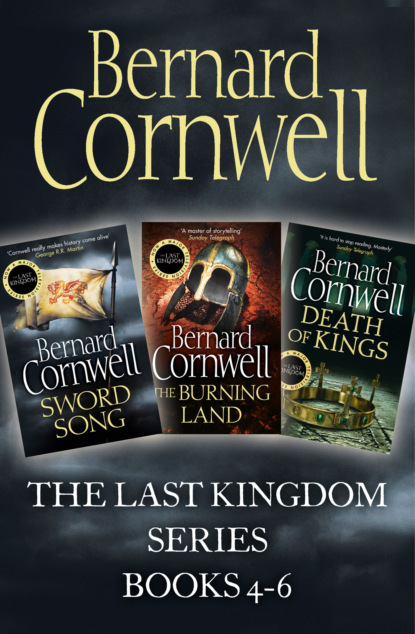

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘We’ll take a look,’ I said, and so we rowed around the island’s eastern tip, and discovered that Finan was right. Over half of Sigefrid’s ships had left the little River Hothlege.

Only three days before there had been thirty-six masts in the creek and now there were just fourteen. I knew the missing ships had not gone upriver towards Lundene, for we would have seen them, and that left only two choices. Either they had gone east and north about the East Anglian coast, or else they had rowed south to make another raid into Cent. The sun, so hot and high and bright, winked reflected dazzling light from the spear-points on the ramparts of the high camp. Men watched us from that high wall, and they saw us turn and hoist our sails and use a small north-east wind that had stirred since dawn to carry us south across the estuary. I was looking for a great smear of smoke that would tell me a raiding party had landed to attack, plunder and burn some town, but the sky over Cent was clear. We dropped the sail and rowed east towards the Medwæg’s mouth, and still saw no smoke, and then Finan, sharp-eyed and posted in our bows, saw the ships.

Six ships.

I was looking for a fleet of at least twenty boats, not some small group of ships, and at first I took no notice, assuming the six were merchant ships keeping company as they rowed towards Lundene, but then Finan came hurrying back between the rowers’ benches. ‘They’re warships,’ he said.

I peered eastwards. I could see the dark flecks of the hulls, but my eyes were not so keen as Finan’s and I could not make out their shapes. The six hulls flickered in the heat haze. ‘Are they moving?’ I asked.

‘No, lord.’

‘Why anchor there?’ I wondered. The ships were on the far side of the Medwæg’s mouth, just off the point called Scerhnesse, which means ‘bright headland’, and it was a strange place to anchor for the currents swirled strong off the low point.

‘I think they’re grounded, lord,’ Finan said. If the ships had been anchored I would have assumed they were waiting for the flood tide to carry them upriver, but grounded boats usually meant men had gone ashore, and the only reason to go ashore was to find plunder.

‘But there’s nothing left to steal on Scaepege,’ I said, puzzled. Scerhnesse lay at the western end of Scaepege, which was an island on the southern side of the Temes’s estuary, and Scaepege had been harried and harrowed and harried again by Viking raids. Few folk lived there, and those that did hid in the creeks. The channel between Scaepege and the mainland was known as the Swealwe, and whole Viking fleets had sheltered there in bad weather. Scaepege and the Swealwe were dangerous places, but not places to find silver or slaves.

‘We’ll go closer,’ I said. Finan went back to the prow as Ralla, in Sword of the Lord, pulled abreast of the Sea-Eagle. I pointed at the distant ships. ‘We’re taking a look at those six boats!’ I called across the gap. Ralla nodded, shouted an order, and his oars bit into the water.

I saw Finan was right as we crossed the Medwæg’s wide mouth; the six were warships, all of them longer and leaner than any cargo-carrying vessel, and all six had been beached. A trickle of smoke drifted south and west, suggesting the crews had lit a fire ashore. I could see no beast-heads on the prows, but that meant nothing. Viking crews might well regard the whole of Scaepege as Danish territory and so take down their dragons, eagles, ravens and serpents to prevent frightening the spirits of the island.

I called Clapa to the steering-oar. ‘Take her straight towards the ships,’ I ordered him, then went forward to join Finan in the prow. Osferth was on one of the oars, sweating and glowering. ‘Nothing like rowing to put on muscle,’ I told him cheerfully, and was rewarded with a scowl.

I clambered up beside the Irishman. ‘They look like Danes,’ he greeted me.

‘We can’t fight six crews,’ I said.

Finan scratched his groin. ‘They making a camp there, you think?’ That was a nasty thought. It was bad enough that Sigefrid’s ships sailed from the northern side of the estuary, without another vipers’ nest being built on the southern bank.

‘No,’ I said, because for once my eyes had proved sharper than the Irishman’s. ‘No,’ I said, ‘they’re not making a camp.’ I touched my amulet.

Finan saw the gesture and heard the anger in my voice. ‘What?’ he asked.

‘The ship on the left,’ I said, pointing, ‘that’s Rodbora.’ I had seen the cross mounted on the stem-post.

Finan’s mouth opened, but he said nothing for a moment. He just stared. Six ships, just six ships, and fifteen had left Lundene. ‘Sweet Jesus Christ,’ Finan finally spoke. He made the sign of the cross. ‘Perhaps the others have gone upriver?’

‘We’d have seen them.’

‘Then they’re coming behind?’

‘You’d better be right,’ I said grimly, ‘or else it’s nine ships gone.’

‘God, no.’

We were close now. The men ashore saw the eagle’s head on my boat and took me for a Viking and some ran into the shallows between two of the stranded ships and made a shield wall there, daring me to attack. ‘That’s Steapa,’ I said, seeing the huge figure at the centre of the shield wall. I ordered the eagle taken down, then stood with my arms outstretched, empty-handed, to show I came in peace. Steapa recognised me, and the shields went down and the weapons were sheathed. A moment later Sea-Eagle’s bows slid soft onto the sandy mud. The tide was rising, so she was safe.

I dropped over the side into water that came to my waist and waded ashore. I reckoned there were at least four hundred men on the beach, far too many for just six ships and, as I neared the shore, I could see that many of those men were wounded. They lay with blood-soaked bandages and pale faces. Priests knelt among them while, at the top of the beach, where pale grass topped the low dunes, I could see that crude driftwood crosses had been driven into newly dug graves.

Steapa waited for me, his face grimmer than ever. ‘What happened?’ I asked him.

‘Ask him,’ Steapa said, sounding bitter. He jerked his head along the beach and I saw Æthelred sitting close to the fire on which a cooking pot bubbled gently. His usual entourage was with him, including Aldhelm, who watched me with a resentful face. None of them spoke as I walked towards them. The fire crackled. Æthelred was toying with a piece of bladderwrack and, though he must have been aware of my approach, he did not look up.

I stopped beside the fire. ‘Where are the other nine ships?’ I asked.

Æthelred’s face jerked up, as though he were surprised to see me. He smiled. ‘Good news,’ he said. He expected me to ask what that news was, but I just watched him and said nothing. ‘We have won,’ he said expansively, ‘a great victory!’

‘A magnificent victory,’ Aldhelm interjected.

I saw that Æthelred’s smile was forced. His next words were halting, as if it took a great effort to string them together. ‘Gunnkel,’ he said, ‘has been taught the power of our swords.’

‘We burned their ships!’ Aldhelm boasted.

‘And made great slaughter,’ Æthelred said, and I saw that his eyes were glistening.

I looked up and down the beach where the wounded lay and where the uninjured sat with bowed heads. ‘You left with fifteen ships,’ I said.

‘We burned their ships,’ Æthelred said, and I thought he was going to cry.

‘Where are the other nine ships?’ I demanded.

‘We stopped here,’ Aldhelm said, and he must have thought I was being critical of their decision to beach the boats, ‘because we could not row against the falling tide.’

‘The other nine ships?’ I asked again, but received no answer. I was still searching the beach and what I sought I could not find. I looked back at Æthelred, whose head had dropped again, and I feared to ask the next question, but it had to be asked. ‘Where is your wife?’ I demanded.

Silence.

‘Where,’ I spoke louder, ‘is Æthelflaed?’

A gull sounded its harsh, forlorn cry. ‘She is taken,’ Æthelred said at last in a voice so small that I could barely hear him.

‘Taken?’

‘A captive,’ Æthelred said, his voice still low.

‘Sweet Jesus Christ,’ I said, using Finan’s favourite expletive. The wind stirred the bitter smoke into my face. For a moment I did not believe what I had heard, but all around me was evidence that Æthelred’s magnificent victory had really been a catastrophic defeat. Nine ships were gone, but ships could be replaced, and half of Æthelred’s troops were missing, yet new men could be found to replace those dead, but what could replace a king’s daughter? ‘Who has her?’ I asked.

‘Sigefrid,’ Aldhelm muttered.

Which explained where the missing ships from Beamfleot had gone.

And Æthelflaed, sweet Æthelflaed, to whom I had made an oath, was a captive.

Our eight ships rode the flooding tide back up the Temes to Lundene. It was a summer’s evening, limpid and calm, in which the sun seemed to linger like a giant red globe suspended in the veil of smoke that clouded the air above the city. Æthelred made the voyage in Rodbora and, when I let Sea-Eagle drop back to row alongside that ship, I saw the black streaks where blood had stained her timbers. I quickened the oar strokes and pulled ahead again.

Steapa travelled with me in the Sea-Eagle and the big man told me what had happened in the River Sture.

It had, indeed, been a magnificent victory. Æthelred’s fleet had surprised the Vikings as they made their encampment on the river’s southern bank. ‘We came at dawn,’ Steapa said.