По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

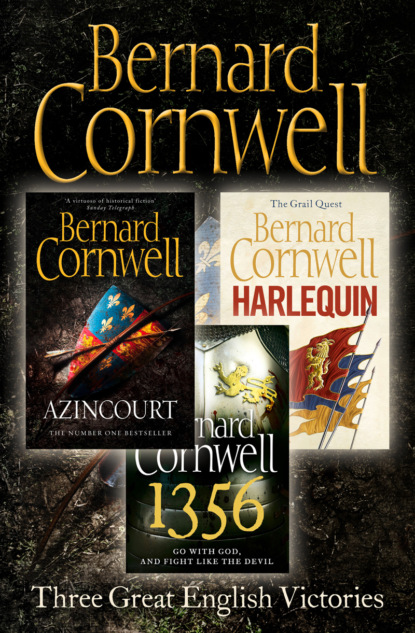

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It’ll clear,’ Skeat said dourly. He rarely called the Earl ‘my lord’, addressing him instead as an equal which, to Sir Simon’s amazement, the Earl seemed to like.

‘And it’s only spitting,’ the Earl said, peering out from the tent and letting in a swirl of damp, cold air. ‘Bowstrings will pluck in this.’

‘So will crossbow cords,’ Richard Totesham interjected. ‘Bastards,’ he added. What made the English failure so galling was that La Roche-Derrien’s defenders were not soldiers but townsfolk: fishermen and boatbuilders, carpenters and masons, and even the Blackbird, a woman! ‘And the rain might stop,’ Totesham went on, ‘but the ground will be slick. It’ll be bad footing under the walls.’

‘Don’t go tonight,’ Will Skeat advised. ‘Let my boys go in by the river tomorrow morning.’

The Earl rubbed the wound on his scalp. For a week now he had assaulted La Roche-Derrien’s southern wall and he still believed his men could take those ramparts, yet he also sensed the pessimism among his hounds of war. One more repulse with another twenty or thirty dead would leave his army dispirited and with the prospect of trailing back to Finisterre with nothing accomplished. ‘Tell me again,’ he said.

Skeat wiped his nose on his leather sleeve. ‘At low tide,’ he said, ‘there’s a way round the north wall. One of my lads was down there last night.’

‘We tried it three days ago,’ one of the knights objected.

‘You tried the downriver side,’ Skeat said. ‘I want to go upriver.’

‘That side has stakes just like the other,’ the Earl said.

‘Loose,’ Skeat responded. One of the Breton captains translated the exchange for his companions. ‘My boy pulled a stake clean out,’ Skeat went on, ‘and he reckons half a dozen others will lift or break. They’re old oak trunks, he says, instead of elm, and they’re rotted through.’

‘How deep is the mud?’ the Earl asked.

‘Up to his knees.’

La Roche-Derrien’s wall encompassed the west, south and east of the town, while the northern side was defended by the River Jaudy, and where the semicircular wall met the river the townsfolk had planted huge stakes in the mud to block access at low tide. Skeat was now suggesting there was a way through those rotted stakes, but when the Earl’s men had tried to do the same thing at the eastern side of the town the attackers had got bogged down in the mud and the townsfolk had picked them off with bolts. It had been a worse slaughter than the repulses in front of the southern gate.

‘But there’s still a wall on the riverbank,’ the Earl pointed out.

‘Aye,’ Skeat allowed, ‘but the silly bastards have broken it down in places. They’ve built quays there, and there’s one right close to the loose stakes.’

‘So your men will have to remove the stakes and climb the quays, all under the gaze of men on the wall?’ the Earl asked sceptically.

‘They can do it,’ Skeat said firmly.

The Earl still reckoned his best chance of success was to close his archers on the south gate and pray that their arrows would keep the defenders cowering while his men-at-arms assaulted the breach, yet that, he conceded, was the plan that had failed earlier in the day and on the day before that. And he had, he knew, only a day or two left. He possessed fewer than three thousand men, and a third of those were sick, and if he could not find them shelter he would have to march back west with his tail between his legs. He needed a town, any town, even La Roche-Derrien.

Will Skeat saw the worries on the Earl’s broad face. ‘My lad was within fifteen paces of the quay last night,’ he asserted. ‘He could have been inside the town and opened the gate.’

‘So why didn’t he?’ Sir Simon could not resist asking. ‘Christ’s bones!’ he went on. ‘But I’d have been inside!’

‘You’re not an archer,’ Skeat said sourly, then made the sign of the cross. At Guingamp one of Skeat’s archers had been captured by the defenders, who had stripped the hated bowman naked then cut him to pieces on the rampart where the besiegers could see his long death. His two bow fingers had been severed first, then his manhood, and the man had screamed like a pig being gelded as he bled to death on the battlements.

The Earl gestured for a servant to replenish the cups of mulled wine. ‘Would you lead this attack, Will?’ he asked.

‘Not me,’ Skeat said. ‘I’m too old to wade through boggy mud. I’ll let the lad who went past the stakes last night lead them in. He’s a good boy, so he is. He’s a clever bastard, but an odd one. He was going to be a priest, he was, only he met me and came to his senses.’

The Earl was plainly tempted by the idea. He toyed with the hilt of his sword, then nodded. ‘I think we should meet your clever bastard. Is he near?’

‘Left him outside,’ Skeat said, then twisted on his stool. ‘Tom, you savage! Come in here!’

Thomas stooped into the Earl’s tent, where the gathered captains saw a tall, long-legged young man dressed entirely in black, all but for his mail coat and the red cross sewn onto his tunic. All the English troops wore that cross of St George so that in a mêlée they would know who was a friend and who an enemy. The young man bowed to the Earl, who realized he had noticed this archer before, which was hardly surprising for Thomas was a striking-looking man. He wore his black hair in a pigtail, tied with bowcord, he had a long bony nose that was crooked, a clean-shaven chin and watchful, clever eyes, though perhaps the most noticeable thing about him was that he was clean. That and, on his shoulder, the great bow that was one of the longest the Earl had seen, and not only long, but painted black, while mounted on the outer belly of the bow was a curious silver plate which seemed to have a coat of arms engraved on it. There was vanity here, the Earl thought, vanity and pride, and he approved of both things.

‘For a man who was up to his knees in river mud last night,’ the Earl said with a smile, ‘you’re remarkably clean.’

‘I washed, my lord.’

‘You’ll catch cold!’ the Earl warned him. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Thomas of Hookton, my lord.’

‘So tell me what you found last night, Thomas of Hookton.’

Thomas told the same tale as Will Skeat. How, after dark, and as the tide fell, he had waded out into the Jaudy’s mud. He had found the fence of stakes ill-maintained, rotting and loose, and he had lifted one out of its socket, wriggled through the gap and gone a few paces towards the nearest quay. ‘I was close enough, my lord, to hear a woman singing,’ he said. The woman had been singing a song that his own mother had crooned to him when he was small and he had been struck by that oddity.

The Earl frowned when Thomas finished, not because he disapproved of anything the archer had said, but because the scalp wound that had left him unconscious for an hour was throbbing. ‘What were you doing at the river last night?’ he asked, mainly to give himself more time to think about the idea.

Thomas said nothing.

‘Another man’s woman,’ Skeat eventually answered for Thomas, ‘that’s what he was doing, my lord, another man’s woman.’

The assembled men laughed, all but Sir Simon Jekyll, who looked sourly at the blushing Thomas. The bastard was a mere archer yet he was wearing a better coat of mail than Sir Simon could afford! And he had a confidence that stank of impudence. Sir Simon shuddered. There was an unfairness to life which he did not understand. Archers from the shires were capturing horses and weapons and armour while he, a champion of tournaments, had not managed anything more valuable than a pair of goddamned boots. He felt an irresistible urge to deflate this tall, composed archer.

‘One alert sentinel, my lord,’ Sir Simon spoke to the Earl in Norman French so that only the handful of well-born men in the tent would understand him, ‘and this boy will be dead and our attack will be floundering in river mud.’

Thomas gave Sir Simon a very level look, insolent in its lack of expression, then answered in fluent French. ‘We should attack in the dark,’ he said, then turned back to the Earl. ‘The tide will be low just before dawn tomorrow, my lord.’

The Earl looked at him with surprise. ‘How did you learn French?’

‘From my father, my lord.’

‘Do we know him?’

‘I doubt it, my lord.’

The Earl did not pursue the subject. He bit his lip and rubbed the pommel of his sword, a habit when he was thinking.

‘All well and good if you get inside,’ Richard Totesham, seated on a milking stool next to Will Skeat, growled at Thomas. Totesham led the largest of the independent bands and had, on that account, a greater authority than the rest of the captains. ‘But what do you do when you’re inside?’

Thomas nodded, as though he had expected the question. ‘I doubt we can reach a gate,’ he said, ‘but if I can put a score of archers onto the wall beside the river then they can protect it while ladders are placed.’

‘And I’ve got two ladders,’ Skeat added. ‘They’ll do.’

The Earl still rubbed the pommel of his sword. ‘When we tried to attack by the river before,’ he said, ‘we got trapped in the mud. It’ll be just as deep where you want to go.’

‘Hurdles, my lord,’ Thomas said. ‘I found some in a farm.’ Hurdles were fence sections made of woven willow that could make a quick pen for sheep or could be laid flat on mud to provide men with footing.

‘I told you he was clever,’ Will Skeat said proudly. ‘Went to Oxford, didn’t you, Tom?’

‘When I was too young to know better,’ Thomas said drily.