По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

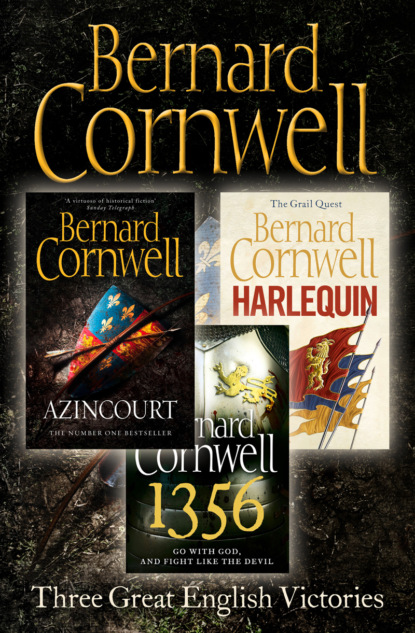

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You are confident of passing the stakes?’ he asked Thomas.

‘I wouldn’t be going otherwise,’ Thomas said, not bothering to sound respectful.

Thomas’s tone made Sir Simon bridle, but he controlled his temper. ‘The Earl,’ he said distantly, ‘has given me the honour of leading the attack on the walls.’ He stopped abruptly and Thomas waited, expecting more, but Sir Simon merely looked at him with an irritated face.

‘So Thomas takes the walls,’ Skeat finally spoke, ‘to make it safe for your ladders?’

‘What I do not want,’ Sir Simon ignored Skeat and spoke to Thomas, ‘is for you to take your men ahead of mine into the town itself. We see armed men, we’re likely to kill them, you understand?’

Thomas almost spat in derision. His men would be armed with bows and no enemy carried a long-stave bow like the English so there was hardly any chance of being mistaken for the town’s defenders, but he held his tongue. He just nodded.

‘You and your archers can join our attack,’ Sir Simon went on, ‘but you will be under my command.’

Thomas nodded again and Sir Simon, irritated by the implied insolence, turned on his heel and walked away.

‘Goddamn bastard,’ Thomas said.

‘He just wants to get his nose into the trough ahead of the rest of us,’ Skeat said.

‘You’re letting the bastard use our ladders?’ Thomas asked.

‘If he wants to be first up, let him. Ladders are green wood, Tom, and if they break I’d rather it was him tumbling than me. Besides, I reckon we’ll be better off following you through the river, but I ain’t telling Sir Simon that.’ Skeat grinned, then swore as a crash sounded from the darkness south of the river. ‘Those bloody white rats,’ Skeat said, and vanished into the shadows.

The white rats were the Bretons loyal to Duke John, men who wore his badge of a white ermine, and some sixty Breton crossbowmen had been attached to Skeat’s soldiers, their job to rattle the walls with their bolts as the ladders were placed against the ramparts. It was those men who had startled the night with their noise and now the noise grew even louder. Some fool had tripped in the dark and thumped a crossbowman with a pavise, the huge shield behind which the crossbows were laboriously reloaded, and the crossbowman struck back, and suddenly the white rats were having a brawl in the dark. The defenders, naturally, heard them and started to hurl burning bales of straw over the ramparts and then a church bell began to toll, then another, and all this long before Thomas had even started across the mud.

Sir Simon Jekyll, alarmed by the bells and the burning straw, shouted that the attack must go in now. ‘Carry the ladders forward!’ he bellowed. Defenders were running onto La Roche-Derrien’s walls and the first crossbow bolts were spitting off the ramparts that were lit bright by the burning bales.

‘Hold those goddamn ladders!’ Will Skeat snarled at his men, then looked at Thomas. ‘What do you reckon?’

‘I think the bastards are distracted,’ Thomas said.

‘So you’ll go?’

‘Got nothing better to do, Will.’

‘Bloody white rats!’

Thomas led his men onto the mud. The hurdles were some help, but not as much as he had hoped, so that they still slipped and struggled their way towards the great stakes and Thomas reckoned the noise they made was enough to wake King Arthur and his knights. But the defenders were making even more noise. Every church bell was clanging, a trumpet was screaming, men were shouting, dogs barking, cockerels were crowing, and the crossbows were creaking and banging as their cords were inched back and released.

The walls loomed to Thomas’s right. He wondered if the Blackbird was up there. He had seen her twice now and been captivated by the fierceness of her face and her wild black hair. A score of other archers had seen her too, and all of them men who could thread an arrow through a bracelet at a hundred paces, yet the woman still lived. Amazing, Thomas thought, what a pretty face could do.

He threw down the last hurdle and so reached the wooden stakes, each one a whole tree trunk sunk into the mud. His men joined him and they heaved against the timber until the rotted wood split like straw. The stakes made a terrible noise as they fell, but it was drowned by the uproar in the town. Jake, the cross-eyed murderer from Exeter gaol, pulled himself alongside Thomas. To their right now was a wooden quay with a rough ladder at one end. Dawn was coming and a feeble, thin, grey light was seeping from the east to outline the bridge across the Jaudy. It was a handsome stone bridge with a barbican at its further end, and Thomas feared the garrison of that tower might see them, but no one called an alarm and no crossbow bolts thumped across the river.

Thomas and Jake were first up the quay ladder, then came Sam, the youngest of Skeat’s archers. The wooden landing stage served a timberyard and a dog began barking frantically among the stacked trunks, but Sam slipped into the blackness with his knife and the barking suddenly stopped. ‘Good doggy,’ Sam said as he came back.

‘String your bows,’ Thomas said. He had looped the hemp cord onto his own black weapon and now untied the laces of his arrow bag.

‘I hate bloody dogs,’ Sam said. ‘One bit my mother when she was pregnant with me.’

‘That’s why you’re daft,’ Jake said.

‘Shut your goddamn faces,’ Thomas ordered. More archers were climbing the quay, which was swaying alarmingly, but he could see that the walls he was supposed to capture were thick with defenders now. English arrows, their white goose feathers bright in the flamelight of the defenders’ fires, flickered over the wall and thumped into the town’s thatched roofs. ‘Maybe we should open the south gate,’ Thomas suggested.

‘Go through the town?’ Jake asked in alarm.

‘It’s a small town,’ Thomas said.

‘You’re mad,’ Jake said, but he was grinning and he meant the words as a compliment.

‘I’m going anyway,’ Thomas said. It would be dark in the streets and their long bows would be hidden. He reckoned it would be safe enough.

A dozen men followed Thomas while the rest started plundering the nearer buildings. More and more men were coming through the broken stakes now as Will Skeat sent them down the riverbank rather than wait for the wall to be captured. The defenders had seen the men in the mud and were shooting down from the end of the town wall, but the first attackers were already loose in the streets.

Thomas blundered through the town. It was pitch-black in the alleys and hard to tell where he was going, though by climbing the hill on which the town was built he reckoned he must eventually go over the summit and so down to the southern gate. Men ran past him, but no one could see that he and his companions were English. The church bells were deafening. Children were crying, dogs howling, gulls screaming, and the noise was making Thomas terrified. This was a daft idea, he thought. Maybe Sir Simon had already climbed the walls? Maybe he was wasting his time? Yet white-feathered arrows still thumped into the town roofs, suggesting the walls were untaken, and so he forced himself to keep going. Twice he found himself in a blind alley and the second time, doubling back into a wider street, he almost ran into a priest who had come from his church to fix a flaming torch in a wall bracket.

‘Go to the ramparts!’ the priest said sternly, then saw the long bows in the men’s hands and opened his mouth to shout the alarm.

He never had time to shout for Thomas’s bowstave slammed point-first into his belly. He bent over, gasping, and Jake casually slit his throat. The priest gurgled as he sank to the cobbles and Jake frowned when the noise stopped.

‘I’ll go to hell for that,’ he said.

‘You’re going to hell anyway,’ Sam said, ‘we all are.’

‘We’re all going to heaven,’ Thomas said, ‘but not if we dawdle.’ He suddenly felt much less frightened, as though the priest’s death had taken his fear. An arrow struck the church tower and dropped into the alley as Thomas led his men past the church and found himself on La Roche-Derrien’s main street, which dropped down to where a watch fire burned by the southern gate. Thomas shrank back into the alley beside the church, for the street was thick with men, but they were all running to the threatened side of the town, and when Thomas next looked the hill was empty. He could only see two sentinels on the ramparts above the gate arch. He told his men about the two sentries.

‘They’re going to be scared as hell,’ he said. ‘We kill the bastards and open the gate.’

‘There might be others,’ Sam said. ‘There’ll be a guard house.’

‘Then kill them too,’ Thomas said. ‘Now, come on!’

They stepped into the street, ran down a few yards and there drew their bows. The arrows flew and the two guards on the arch fell. A man stepped out of the guard house built into the gate turret and gawped at the archers, but before any could draw their bows he stepped back inside and barred the door.

‘It’s ours!’ Thomas shouted, and led his men in a wild rush to the arch.

The guard house stayed locked so there was no one to stop the archers from lifting the bar and pushing open the two great gates. The Earl’s men saw the gates open, saw the English archers outlined against the watch fire and gave a great roar from the darkness that told Thomas a torrent of vengeful troops was coming towards him.

Which meant La Roche-Derrien’s time of weeping could begin. For the English had taken the town.

Jeanette woke to a church bell ringing as though it was the world’s doom when the dead were rising from their graves and the gates of hell were yawning wide for sinners. Her first instinct was to cross to her son’s bed, but little Charles was safe. She could just see his eyes in the dark that was scarcely alleviated by the glowing embers of the fire.

‘Mama?’ he cried, reaching up to her.

‘Quiet,’ she hushed the boy, then ran to throw open the shutters. A faint grey light showed above the eastern roofs, then steps sounded in the street and she leaned from the window to see men running from their houses with swords, crossbows and spears. A trumpet was calling from the town centre, then more church bells began tolling the alarm into a dying night. The bell of the church of the Virgin was cracked and made a harsh, anvil-like noise that was all the more terrifying.

‘Madame!’ a servant cried as she ran into the room.

‘The English must be attacking.’ Jeanette forced herself to speak calmly. She was wearing nothing but a linen shift and was suddenly cold. She snatched up a cloak, tied it about her neck, then took her son into her arms. ‘You will be all right, Charles,’ she tried to console him. ‘The English are attacking again, that is all.’