По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

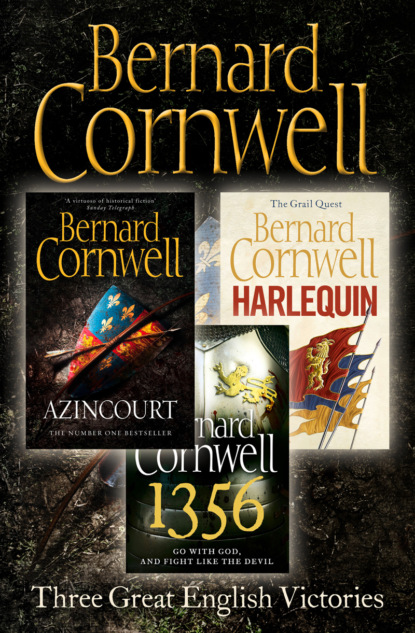

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Very small, my lord,’ the clerk, whose nose was running, spoke from memory. ‘There is a holding in Finisterre which is already in our hands, some houses in Guingamp, I believe, but nothing else.’

‘There,’ the Earl said, turning back to Sir Simon. ‘What advantages will we make from a penniless three-year-old?’

‘Not penniless,’ Sir Simon protested. ‘I took a rich armour there.’

‘Which the boy’s father doubtless took in battle!’

‘And the house is wealthy.’ Sir Simon was getting angry. ‘There are ships, storehouses, stables.’

‘The house,’ the clerk sounded bored, ‘belonged to the Count’s father-in-law. A dealer in wine, I believe.’

The Earl raised a quizzical eyebrow at Sir Simon, who was shaking his head at the clerk’s obstinacy. ‘The boy, my lord,’ Sir Simon responded with an elaborate courtesy which bordered on insolence, ‘is kin to Charles of Blois.’

‘But being penniless,’ the Earl said, ‘I doubt he provokes fondness. More of a burden, wouldn’t you think? Besides, what would you have me do? Make the child give fealty to the real Duke of Brittany? The real Duke, Sir Simon, is a five-year-old child in London. It’ll be a nursery farce! A three-year-old bobbing down to a five-year-old! Do their wet nurses attend them? Shall we feast on milk and penny-cakes after? Or maybe we can enjoy a game of hunt the slipper when the ceremony is over?’

‘The Countess fought us from the walls!’ Sir Simon attempted a last protest.

‘Do not dispute me!’ the Earl shouted, thumping the arm of his chair. ‘You forget that I am the King’s deputy and have his powers.’ The Earl leaned back, taut with anger, and Sir Simon swallowed his own fury, but could not resist muttering that the Countess had used a crossbow against the English.

‘Is she the Blackbird?’ Thomas asked Skeat.

‘The Countess? Aye, that’s what they say.’

‘She’s a beauty.’

‘After what I found you prodding this morning,’ Skeat said, ‘how can you tell?’

The Earl gave an irritated glance at Skeat and Thomas, then looked back to Sir Simon. ‘If the Countess did fight us from the walls,’ he said, ‘then I admire her spirit. As for the other matters …’ He paused and sighed. Belas looked expectant and Sir Simon wary. ‘The two ships,’ the Earl decreed, ‘are prizes and they will be sold in England or else taken into royal service, and you, Sir Simon, will be awarded one-third of their value.’ That ruling was according to the law. The King would take a third, the Earl another and the last portion went to the man who had captured the prize. ‘As to the sword and armour …’ The Earl paused again. He had rescued Jeanette from rape and he had liked her, and he had seen the anguish on her face and listened to her impassioned plea that she owned nothing that had belonged to her husband except the precious armour and the beautiful sword, but such things, by their very nature, were the legitimate plunder of war. ‘The armour and weapons and horses are yours, Sir Simon,’ the Earl said, regretting the judgement but knowing it was fair. ‘As to the child, I decree he is under the protection of the Crown of England and when he is of age he can decide his own fealty.’ He glanced at the clerks to make sure they were noting down his decisions. ‘You tell me you wish to billet yourself in the widow’s house?’ he asked Sir Simon.

‘I took it,’ Sir Simon said curtly.

‘And stripped it bare, I hear,’ the Earl observed icily. ‘The Countess claims you stole money from her.’

‘She lies.’ Sir Simon looked indignant. ‘Lies, my lord, lies!’

The Earl doubted it, but he could hardly accuse a gentleman of perjury without provoking a duel and, though William Bohun feared no man except his king, he did not want to fight over so petty a matter. He let it drop. ‘However,’ he went on, ‘I did promise the lady protection against harassment.’ He stared at Sir Simon as he spoke, then looked at Will Skeat, and changed to English. ‘You’d like to keep your men together, Will?’

‘I would, my lord.’

‘Then you’ll have the widow’s house. And she is to be treated honourably, you hear me? Honourably! Tell your men that, Will!’

Skeat nodded. ‘I’ll cut their ears off if they touch her, my lord.’

‘Not their ears, Will. Slice something more suitable away. Sir Simon will show you the house and you, Sir Simon,’ the Earl spoke French again, ‘will find a bed elsewhere.’

Sir Simon opened his mouth to protest, but one look from the Earl quietened him. Another petitioner came forward, wanting redress for a cellar full of wine that had been stolen, but the Earl diverted him to a clerk who would record the man’s complaints on a parchment which the Earl doubted he would ever find time to read.

Then he beckoned to Thomas. ‘I have to thank you, Thomas of Hookton.’

‘Thank me, my lord?’

The Earl smiled. ‘You found a way into the town when everything else we’d tried had failed.’

Thomas reddened. ‘It was a pleasure, my lord.’

‘You can claim a reward of me,’ the Earl said. ‘It’s customary.’

Thomas shrugged. ‘I’m happy, my lord.’

‘Then you’re a lucky man, Thomas. But I shall remember the debt. And thank you, Will.’

Will Skeat grinned. ‘If this lump of a daft fool don’t want a reward, my lord, I’ll take it.’

The Earl liked that. ‘My reward to you, Will, is to leave you here. I’m giving you a whole new stretch of countryside to lay waste. God’s teeth, you’ll soon be richer than me.’ He stood. ‘Sir Simon will guide you to your quarters.’

Sir Simon might have bridled at the curt order to be a mere guide, but surprisingly he obeyed without showing any resentment, perhaps because he wanted another chance to meet Jeanette. And so, at midday, he led Will Skeat and his men through the streets to the big house beside the river. Sir Simon had put on his new armour and wore it without any surcoat so that the polished plate and gold embossment shone bright in the feeble winter sun. He ducked his helmeted head under the yard’s archway and immediately Jeanette came running from the kitchen door, which lay just to the gate’s left.

‘Get out!’ she shouted in French, ‘get out!’

Thomas, riding close behind Sir Simon, stared at her. She was indeed the Blackbird and she was as beautiful at close range as she had been when he had glimpsed her on the walls.

‘Get out, all of you!’ She stood, hands on her hips, bareheaded, shouting.

Sir Simon pushed up the pig-snout visor of the helmet. ‘This house is commandeered, my lady,’ he said happily. ‘The Earl ordered it.’

‘The Earl promised I would be left alone!’ Jeanette protested hotly.

‘Then his lordship has changed his mind,’ Sir Simon said.

She spat at him. ‘You have already stolen everything else of mine, now you would take the house too?’

‘Yes, madame,’ Sir Simon said, and he spurred the horse forward so that it crowded her. ‘Yes, madame,’ he said again, then wrenched the reins so that the horse twisted and thumped into Jeanette, throwing her onto the ground. ‘I’ll take your house,’ Sir Simon said, ‘and anything else I want, madame.’ The watching archers cheered at the sight of Jeanette’s long bare legs. She snatched her skirts down and tried to stand, but Sir Simon edged his horse forward to force her into an undignified scramble across the yard.

‘Let the lass up!’ Will Skeat shouted angrily.

‘She and I are old friends, Master Skeat,’ Sir Simon answered, still threatening Jeanette with the horse’s heavy hooves.

‘I said let her up and leave her be!’ Will snarled.

Sir Simon, offended at being ordered by a commoner and in front of archers, turned angrily, but there was a competence about Will Skeat that gave the knight pause. Skeat was twice Sir Simon’s age and all those years had been spent in fighting, and Sir Simon retained just enough sense not to make a confrontation. ‘The house is yours, Master Skeat,’ he said condescendingly, ‘but look after its mistress. I have plans for her.’ He backed the horse from Jeanette, who was in tears of shame, then spurred out of the yard.

Jeanette did not understand English, but she recognized that Will Skeat had intervened on her behalf and so she stood and appealed to him. ‘He has stolen everything from me!’ she said, pointing at the retreating horseman. ‘Everything!’

‘You know what the lass is saying, Tom?’ Skeat asked.

‘She doesn’t like Sir Simon,’ Thomas said laconically. He was leaning on his saddle pommel, watching Jeanette.

‘Calm the girl down, for Christ’s sake,’ Skeat pleaded, then turned in his saddle. ‘Jake? Make sure there’s water and hay for horses. Peter, kill two of them heifers so we can sup before the light goes. Rest of you? Stop gawping at the lass and get yourselves settled!’