По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

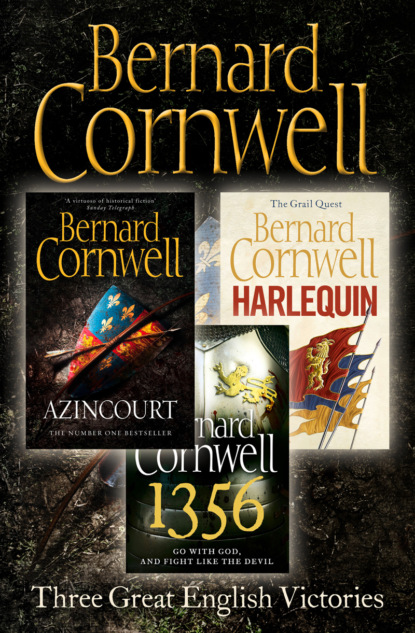

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You’re not a prisoner,’ Thomas said.

Sir Geoffrey seemed perplexed by the words. ‘You release me?’

‘We don’t want you,’ Thomas said. ‘You might think about going to Spain,’ he suggested, ‘or the Holy Land. Not too many hellequin in either place.’

Sir Geoffrey sheathed his sword. ‘I must fight against the enemies of my king so I shall fight here. But I thank you.’ He gathered his reins and just at that moment Sir Simon Jekyll rode out of the trees, pointing his drawn sword at Sir Geoffrey.

‘He’s my prisoner!’ he called to Thomas. ‘My prisoner!’

‘He’s no one’s prisoner,’ Thomas said. ‘We’re letting him go.’

‘You’re letting him go?’ Sir Simon sneered. ‘Do you know who commands here?’

‘What I know,’ Thomas said, ‘is that this man is no prisoner.’ He thumped the trapper-covered rump of Sir Geoffrey’s horse to send it on its way. ‘Spain or the Holy Land!’ he called after Sir Geoffrey.

Sir Simon turned his horse to follow Sir Geoffrey, then saw that Will Skeat was ready to intervene and stop any such pursuit so he turned back to Thomas. ‘You had no right to release him! No right!’

‘He released you,’ Thomas said.

‘Then he was a fool. And because he is a fool, I must be?’ Sir Simon was quivering with anger. Sir Geoffrey might have declared himself a poor man, hardly able to raise a ransom, but his horse alone was worth at least fifty pounds, and Skeat and Thomas had just sent that money trotting southwards. Sir Simon watched him go, then lowered the sword blade so that it threatened Thomas’s throat. ‘From the moment I first saw you,’ he said, ‘you have been insolent. I am the highest-born man on this field and it is I who decide the fate of prisoners. You understand that?’

‘He yielded to me,’ Thomas said, ‘not to you. So it don’t matter what bed you were born in.’

‘You’re a pup!’ Sir Simon spat. ‘Skeat! I want recompense for that prisoner. You hear me?’

Skeat ignored Sir Simon, but Thomas did not have enough sense to do the same.

‘Jesus,’ he said in disgust, ‘that man spared you, and you’d not return the favour? You’re not a bloody knight, you’re just a bully. Go and boil your arse.’

The sword rose and so did Thomas’s bow. Sir Simon looked at the glittering arrow point, its edges feathered white through sharpening and he had just enough wit not to strike with his sword. He sheathed it instead, slamming the blade into the scabbard, then wheeled his destrier and spurred away.

Which left Skeat’s men to sort out the enemy’s dead. There were eighteen of them and another twenty-three grievously wounded. There were also sixteen bleeding horses and twenty-four dead destriers, and that, as Will Skeat remarked, was a wicked waste of good horseflesh.

And Sir Geoffrey had been taught his lesson.

There was a fuss back in La Roche-Derrien. Sir Simon Jekyll complained to Richard Totesham that Will Skeat had failed to support him in battle, then also claimed to have been responsible for the death or wounding of forty-one enemy men-at-arms. He boasted he had won the skirmish, then returned to his theme of Skeat’s perfidy, but Richard Totesham was in no mood to endure Sir Simon’s querulousness. ‘Did you win the fight or not?’

‘Of course we won!’ Sir Simon blinked indignantly. ‘They’re dead, ain’t they?’

‘So why did you need Will’s men-at-arms?’ Totesham asked.

Sir Simon searched for an answer and found none. ‘He was impertinent,’ he complained.

‘That’s for you and him to settle, not me,’ Totesham said in abrupt dismissal, but he was thinking about the conversation and that night he talked with Skeat.

‘Forty-one dead or wounded?’ he wondered aloud. ‘That must be a third of Lannion’s men-at-arms.’

‘Near as maybe, aye.’

Totesham’s quarters were near the river and from his window he could watch the water slide under the bridge arches. Bats flittered about the barbican tower that guarded the bridge’s further side, while the cottages beyond the river were lit by a sharp-edged moon. ‘They’ll be short-handed, Will,’ Totesham said.

‘They’ll not be happy, that’s for sure.’

‘And the place will be stuffed with valuables.’

‘Like as not,’ Skeat agreed. Many folk, fearing the hellequin, had taken their belongings to the nearby fortresses, and Lannion must be filled with their goods. More to the point, Totesham would find food there. His garrison received some food from the farms north of La Roche-Derrien and more was brought across the Channel from England, but the hellequin’s wastage of the countryside had brought hunger perilously close.

‘Leave fifty men here?’ Totesham was still thinking aloud, but he had no need to explain his thoughts to an old soldier like Skeat.

‘We’ll need new ladders,’ Skeat said.

‘What happened to the old ones?’

‘Firewood. It were a cold winter.’

‘A night attack?’ Totesham suggested.

‘Full moon in five or six days.’

‘Five days from now, then,’ Totesham decided. ‘And I’ll want your men, Will.’

‘If they’re sober by then.’

‘They deserve their drink after what they did today,’ Totesham said warmly, then gave Skeat a smile. ‘Sir Simon was complaining about you. Says you were impertinent.’

‘That weren’t me, Dick, it was my lad Tom. Told the bastard to go and boil his arse.’

‘I fear Sir Simon was never one for taking good advice,’ Totesham said gravely.

Nor were Skeat’s men. He had let them loose in the town, but warned them that they would feel rotten in the morning if they drank too much and they ignored that advice to make celebration in La Roche-Derrien’s taverns. Thomas had gone with a score of his friends and their women to an inn where they sang, danced and tried to pick a fight with a group of Duke John’s white rats, who were too sensible to rise to the provocation and slipped quietly into the night. A moment later two men-at-arms walked in, both wearing jackets with the Earl of Northampton’s badge of the lions and the stars. Their arrival was jeered, but they endured it with patience and asked if Thomas was present.

‘He’s the ugly bastard over there,’ Jake said, pointing to Thomas, who was dancing to the music of a flute and drum. The men-at-arms waited till he had finished his dance, then explained that Will Skeat was with the garrison’s commander and wanted to talk with him.

Thomas drained his ale. ‘What it is,’ he told the other archers, ‘is that they can’t make a decision without me. Indispensable, that’s me.’ The archers mocked that, but cheered good-naturedly as Thomas left with the two men-at-arms.

One of them came from Dorset and had actually heard of Hookton. ‘Didn’t the French land there?’ he asked.

‘Bastards wrecked it. I doubt there’s anything left,’ Thomas said. ‘So why does Will want me?’

‘God knows and He ain’t telling,’ one of the men said. He had led Thomas towards Richard Totesham’s quarters, but now he pointed down a dark alley. ‘They’re in a tavern at the end there. Place with the anchor hanging over the door.’

‘Good for them,’ Thomas said. If he had not been half drunk he might have realized that Totesham and Skeat were unlikely to summon him to a tavern, let alone the smallest one in town at the river end of the darkest alley, but Thomas suspected nothing until he was halfway down the narrow passage and two men stepped from a gateway. The first he knew of them was when a blow landed on the back of his head. He pitched forward onto his knees and the second man kicked him in the face, then both men rained kicks and blows on him until he offered no more resistance and they could seize his arms and drag him through the gate into a small smithy. There was blood in Thomas’s mouth, his nose had been broken again, a rib was cracked and his belly was churning with ale.

A fire burned in the smithy. Thomas, through half-closed eyes, could see an anvil. Then more men surrounded him and gave him a second kicking so that he rolled into a ball in a vain attempt to protect himself.

‘Enough,’ a voice said, and Thomas opened his eyes to see Sir Simon Jekyll. The two men who had fetched him from the tavern, and who had seemed so friendly, now came through the smithy gate and stripped off their borrowed tunics showing the Earl of Northampton’s badge. ‘Well done,’ Sir Simon told them, then looked at Thomas. ‘Mere archers,’ Sir Simon said, ‘do not tell knights to boil their arse.’

A tall man, a huge brute with lank yellow hair and blackened teeth, was standing beside Thomas, wanting to kick him if he offered an insolent reply, so Thomas held his tongue. Instead he offered a silent prayer to St Sebastian, the patron saint of archers. This plight, he reckoned, was too serious to be left to a dog.