По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

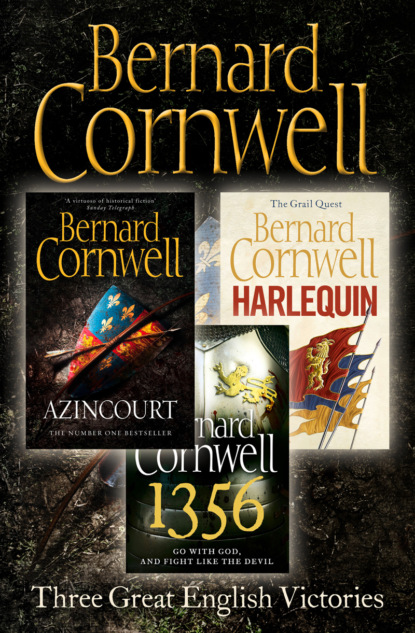

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Take his breeches down, Colley,’ Sir Simon ordered, and turned back to the fire. Thomas saw there was a great three-legged pot standing in the red-hot charcoal. He swore under his breath, realizing that he was the one who was to get a boiled arse. Sir Simon peered into the pot. ‘You are to be taught a lesson in courtesy,’ he told Thomas, who whimpered as the yellow-haired brute cut through his belt, then dragged his breeches down. The other men searched Thomas’s pockets, taking what coins they found and a good knife, then they turned him onto his belly so that his naked arse was ready for the boiling water.

Sir Simon saw the first wisps of steam float from the pot. ‘Take it to him,’ he ordered his men.

Three of Sir Simon’s soldiers were holding Thomas down and he was too hurt and too weak to fight them, so he did the only thing he could. He screamed murder. He filled his lungs and bellowed as loud as he could. He reckoned he was in a small town that was crowded with men and someone must hear and so he shrieked the alarm. ‘Murder! Murder!’ A man kicked his belly, but Thomas went on shouting.

‘For Christ’s sake, silence him,’ Sir Simon snarled, and Colley, the yellow-haired man, kneeled beside Thomas and tried to stuff straw into his mouth, but Thomas managed to spit it out.

‘Murder!’ he screamed. ‘Murder!’

Colley swore, took a handful of filthy mud and slapped it into Thomas’s mouth, muffling his noise. ‘Bastard,’ Colley said, and thumped Thomas’s skull. ‘Bastard!’

Thomas gagged on the mud, but he could not spit it out.

Sir Simon was standing over him now. ‘You are to be taught good manners,’ he said, and watched as the steaming pot was carried across the smithy yard.

Then the gate opened and a newcomer stepped into the yard. ‘What in God’s name is happening here?’ the man asked, and Thomas could have sung a Te Deum in praise of St Sebastian if his mouth had not been crammed with mud, for his rescuer was Father Hobbe, who must have heard the frantic shouting and come running down the alley to investigate. ‘What are you doing?’ the priest demanded of Sir Simon.

‘It is not your business, father,’ Sir Simon said.

‘Thomas, is it you?’ He turned back to the knight. ‘By God, it is my business!’ Father Hobbe had a temper and he lost it now. ‘Who the devil do you think you are?’

‘Be careful, priest,’ Sir Simon snarled.

‘Be careful! Me? I will have your soul in hell if you don’t leave.’ The small priest snatched up the smith’s huge poker and wielded it like a sword. ‘I’ll have all your souls in hell! Leave! All of you! Out of here! Out! In the name of God, get out! Get out!’

Sir Simon backed down. It was one thing to torture an archer, but quite another to get into a fight with a priest whose voice was loud enough to attract still more attention. Sir Simon snarled that Father Hobbe was an interfering bastard, but he retreated all the same.

Father Hobbe knelt beside Thomas and hooked some of the mud from his mouth, along with tendrils of thick blood and a broken tooth. ‘You poor lad,’ Father Hobbe said, then helped Thomas stand. ‘I’ll take you home, Tom, take you home and clean you up.’

Thomas had to vomit first, but then, holding his breeches up, he staggered back to Jeanette’s house, supported all the way by the priest. A dozen archers greeted him, wanting to know what had happened, but Father Hobbe brushed them aside. ‘Where’s the kitchen?’ he demanded.

‘She won’t let us in there,’ Thomas said, his voice indistinct because of his swollen mouth and bleeding gums.

‘Where is it?’ Father Hobbe insisted. One of the archers nodded at the door and the priest just pushed it open and half carried Thomas inside. He sat him on a chair and pulled the rush lights to the table’s edge so he could see Thomas’s face. ‘Dear God,’ he said, ‘what have they done to you?’ He patted Thomas’s hand, then went to find water.

Jeanette came into the kitchen, full of fury. ‘You are not supposed to be here! You will get out!’ Then she saw Thomas’s face and her voice trailed away. If someone had told her that she would see a badly beaten English archer she would have been cheered, but to her surprise she felt a pang of sympathy. ‘What happened?’

‘Sir Simon Jekyll did this,’ Thomas managed to say.

‘Sir Simon?’

‘He’s an evil man.’ Father Hobbe had heard the name and came from the scullery with a big bowl of water. ‘He’s an evil thing, evil.’ He spoke in English. ‘You have some cloths?’ he asked Jeanette.

‘She doesn’t speak English,’ Thomas said. Blood was trickling down his face.

‘Sir Simon attacked you?’ Jeanette asked. ‘Why?’

‘Because I told him to boil his arse,’ Thomas said, and was rewarded with a smile.

‘Good,’ Jeanette said. She did not invite Thomas to stay in the kitchen, but nor did she order him to leave. Instead she stood and watched as the priest washed his face, then took off Thomas’s shirt to bind up the cracked rib.

‘Tell her she could help me,’ Father Hobbe said.

‘She’s too proud to help,’ Thomas said.

‘It’s a sinful sad world,’ Father Hobbe declared, then knelt down. ‘Hold still, Tom,’ he said, ‘for this will hurt like the very devil.’ He took hold of the broken nose and there was the sound of cartilage scraping before Thomas shouted in pain. Father Hobbe put a cold wet cloth over his nose. ‘Hold that there, Tom, and the pain will go. Well, it won’t really, but you’ll get used to it.’ He sat on an empty salt barrel, shaking his head. ‘Sweet Jesus, Tom, what are we going to do with you?’

‘You’ve done it,’ Thomas said, ‘and I’m grateful. A day or two and I’ll be leaping about like a spring lamb.’

‘You’ve been doing that for too long, Tom,’ Father Hobbe said earnestly. Jeanette, not understanding a word, just watched the two men. ‘God gave you a good head,’ the priest went on, ‘but you waste your wits, Tom, you do waste them.’

‘You want me to be a priest?’

Father Hobbe smiled. ‘I doubt you’d be much credit to the Church, Tom. You’d like as not end up as an archbishop because you’re clever and devious enough, but I think you’d be happier as a soldier. But you have debts to God, Tom. Remember that promise you made to your father! You made it in a church, and it would be good for your soul to keep that promise, Tom.’

Thomas laughed, and immediately wished he had not, for the pain whipped through his ribs. He swore, apologized to Jeanette, then looked back to the priest. ‘And how in the name of God, father, am I supposed to keep that promise? I don’t even know what bastard stole the lance.’

‘What bastard?’ Jeanette asked, for she had picked up that one word. ‘Sir Simon?’

‘He is a bastard,’ Thomas said, ‘but he’s not the only one,’ and he told her about the lance, about the day his village had been murdered, about his father dying, and about the man who carried a banner showing three yellow hawks on a blue field. He told the story slowly, through bloody lips, and when he had finished Jeanette shrugged.

‘So you want to kill this man, yes?’

‘One day.’

‘He deserves to be killed,’ Jeanette said.

Thomas stared at her through half-closed eyes, astonished by those words. ‘You know him?’

‘He is called Sir Guillaume d’Evecque,’ Jeanette said.

‘What’s she saying?’ Father Hobbe asked.

‘I know him,’ Jeanette said grimly. ‘In Caen, where he comes from, he is sometimes called the lord of the sea and of the land.’

‘Because he fights on both?’ Thomas guessed.

‘He is a knight,’ Jeanette said, ‘but he is also a sea-raider. A pirate. My father owned sixteen ships and Guillaume d’Evecque stole three of them.’

‘He fought against you?’ Thomas sounded surprised.

Jeanette shrugged. ‘He thinks any ship that is not French is an enemy. We are Bretons.’

Thomas looked at Father Hobbe. ‘There you are, father,’ he said lightly, ‘to keep my promise all I must do is fight the knight of the sea and of the land.’

Father Hobbe had not followed the French, but he shook his head sadly. ‘How you keep the promise, Thomas, is your business. But God knows you made it, and I know you are doing nothing about it.’ He fingered the wooden cross he wore on a leather lace about his neck. ‘And what shall I do about Sir Simon?’

‘Nothing,’ Thomas said.