По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

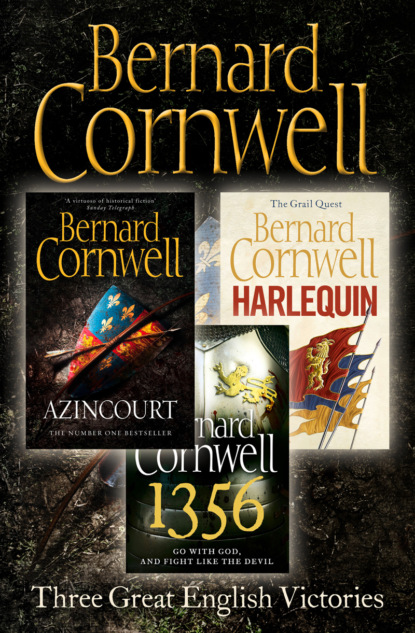

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Cross-eyed Jake saw the enemy first. He was gazing south through the pearly mist that lay over the flat land and he saw the shadows in the vapour. At first he thought it was a herd of cows, then he decided it had to be refugees from the town. But then he saw a banner and a lance and the dull grey of a mail coat, and he shouted to Skeat that there were horsemen in sight.

Skeat peered over the ramparts. ‘Can you see anything, Tom?’

It was just before dawn proper and the countryside was suffused with greyness and streaked with mist. Thomas stared. He could see a thick wood a mile or more to the south and a low ridge showing dark above the mist. Then he saw the banners and the grey mail in the grey light, and a thicket of lances.

‘Men-at-arms,’ he said, ‘a lot of the bastards.’

Skeat swore. Totesham’s men were either still in the town or else strung along the road to La Roche-Derrien, and strung so far that there could be no hope of pulling them back behind Lannion’s walls – though even if that had been possible it was not practical for the whole western side of the town was burning furiously and the flames were spreading fast. To retreat behind the walls was to risk being roasted alive, but Totesham’s men were hardly in a fit condition to fight: many were drunk and all were laden with plunder.

‘Hedgerow,’ Skeat said curtly, pointing to a ragged line of blackthorn and elder that ran parallel to the road where the carts rumbled. ‘Archers to the hedge, Tom. We’ll look after your horses. Christ knows how we’ll stop the bastards,’ he made the sign of the cross, ‘but we ain’t got much choice.’

Thomas bullied a passage at the crowded gate and led forty archers across a soggy pasture to the hedgerow that seemed a flimsy barrier against the enemy massing in the silvery mist. There were at least three hundred horsemen there. They were not advancing yet, but instead grouping themselves for a charge, and Thomas had only forty men to stop them.

‘Spread out!’ he shouted. ‘Spread out!’ He briefly went onto one knee and made the sign of the cross. St Sebastian, he prayed, be with us now. St Guinefort, protect me. He touched the desiccated dog’s paw, then made the sign of the cross again.

A dozen more archers joined his force, but it was still far too small. A score of pageboys, mounted on ponies and armed with toy swords, could have massacred the men on the road, for Thomas’s hedge did not provide a complete screen, but rather straggled into nothingness about half a mile from the town. The horsemen only had to ride round that open end and there would be nothing to stop them. Thomas could take his archers into the open ground, but fifty men could not stop three hundred. Archers were at their best when they were massed together so that their arrows made a hard, steel-tipped rain. Fifty men could make a shower, but they would still be overrun and massacred by the horsemen.

‘Crossbowmen,’ Jake grunted, and Thomas saw the men in green and red jackets emerging from the woods behind the enemy men-at-arms. The new dawn light reflected cold from mail, swords and helmets. ‘Bastards are taking their time,’ Jake said nervously. He had planted a dozen arrows in the base of the hedge, which was just thick enough to stop the horsemen, but not nearly dense enough to slow a crossbow bolt.

Will Skeat had gathered sixty of his men-at-arms beside the road, ready to countercharge the enemy whose numbers increased every minute. Duke Charles’s men and their French allies were riding eastwards now, looking to advance about the open end of the hedge where there was an inviting swathe of green and open land leading all the way to the road. Thomas wondered why the hell they were waiting. He wondered if he would die here. Dear God, he thought, but there were not nearly enough men to stop this enemy. The fires continued to burn in Lannion, pouring smoke into the pale sky.

He ran to the left of the line, where he found Father Hobbe holding a bow. ‘You shouldn’t be here, father,’ he said.

‘God will forgive me,’ the priest said. He had tucked his cassock into his belt and had a small stand of arrows stuck into the hedgebank. Thomas gazed at the open land, wondering how long his men would last in that immensity of grass. Just what the enemy wanted, he thought, a stretch of bare flat land on which their horses could run hard and straight. Only the land was not entirely flat for it was dotted with grassy hummocks through which two grey herons walked stiff-legged as they hunted for frogs or ducklings. Frogs, Thomas thought, and ducklings. Sweet God, it was a marsh! The spring had been unusually dry, yet his boots were soaking from the damp field he had crossed to reach the hedgerow. The realization burst on Thomas like the rising sun. The open land was marsh! No wonder the enemy was waiting. They could see Totesham’s men strung out for slaughter, but they could see no way across the swampy ground.

‘This way!’ Thomas shouted at the archers. ‘This way! Hurry! Hurry! Come on, you bastards!’

He led them round the end of the hedge into the swamp where they leaped and splashed through a maze of marsh, tussocks and streamlets. They went south towards the enemy and once in range Thomas spread his men out and told them to indulge in target practice. His fear had gone, replaced by exaltation. The enemy was balked by the marsh. Their horses could not advance, but Thomas’s light archers could leap across the tussocks like demons. Like hellequin.

‘Kill the bastards!’ he shouted.

The white-fledged arrows hissed across the wetland to strike horses and men. Some of the enemy tried to charge the archers, but their horses floundered in the soft ground and became targets for volleys of arrows. The crossbowmen dismounted and advanced, but the archers switched their aim to them, and now more archers were arriving, dispatched by Skeat and Totesham, so that the marsh was suddenly swarming with English and Welsh bowmen who poured a steel-tipped hell on the befuddled enemy. It became a game. Men wagered on whether or not they could strike a particular target. The sun rose higher, casting shadows from the dead horses. The enemy was edging back to the trees. One brave group tried a last charge, hoping to skirt the marsh, but their horses stumbled in the soft ground and the arrows spitted and sliced at them so that men and beasts screamed as they fell. One horseman struggled on, flailing his beast with the flat of his sword. Thomas put an arrow into the horse’s neck and Jake skewered its haunch, and the animal screeched piteously as it thrashed in pain and collapsed into the swamp. The man somehow extricated his feet from his stirrups and stumbled cursing towards the archers with his sword held low and shield high, but Sam buried an arrow in his groin and then a dozen more bowmen added their arrows before swarming over the fallen enemy. Knives were drawn, throats cut, then the business of plunder could begin. The corpses were stripped of their mail and weapons and the horses of their bridles and saddles, then Father Hobbe prayed over the dead while the archers counted their spoils.

The enemy was gone by mid-morning. They left two score of dead men, and twice that number had been wounded, but not a single Welsh or English archer had died.

Duke Charles’s men slunk back to Guingamp. Lannion had been destroyed, they had been humiliated and Will Skeat’s men celebrated in La Roche-Derrien. They were the hellequin, they were the best and they could not be beaten.

The following morning Thomas, Sam and Jake left La Roche-Derrien before daybreak. They rode west towards Lannion, but once in the woods they swerved off the road and picketed their horses deep among the trees. Then, moving like poachers, they worked their way back to the wood’s edge. Each had his own bow slung on his shoulder, and carried a crossbow too, and they practised with the unfamiliar weapons as they waited in a swathe of bluebells at the wood’s margin from where they could see La Roche-Derrien’s western gate. Thomas had only brought a dozen bolts, short and stub-feathered, so each of them shot just two times. Will Skeat had been right: the weapons did kick up as the archers loosed so that their first bolts went high on the trunk that was their target. Thomas’s second shot was more accurate, but nothing like as true as an arrow shot from a proper bow. The near miss made him apprehensive of the morning’s risks, but Jake and Sam were both cheerful at the prospect of larceny and murder.

‘Can’t really miss,’ Sam said after his second shot had also gone high. ‘Might not catch the bastard in the belly, but we’ll hit him somewhere.’ He levered the cord back, grunting with the effort. No man alive could haul a crossbow’s string by arm-power alone and so a mechanism had to be employed. The most expensive crossbows, those with the longest range, used a jackscrew. The archer would place a cranked handle on the screw’s end and wind the cord back, inch by creaking inch, until the pawl above the trigger engaged the string. Some crossbowmen used their bodies as a lever. They wore thick leather belts to which a hook was attached and by bending down, attaching the hook to the cord and then straightening, they could pull the twisted strings back, but the crossbows Thomas had brought from Lannion used a lever, shaped like a goat’s hind leg, that forced the cord and bent the short bow shaft, which was a layered thing of horn, wood and glue. The lever was probably the fastest way of cocking the weapon, though it did not offer the power of a screw-cocked bow and was still slow compared to a yew shaft. In truth there was nothing to compare with the English bow and Skeat’s men debated endlessly why the enemy did not adopt the weapon. ‘Because they’re daft,’ was Sam’s curt judgement, though the truth, Thomas knew, was that other nations simply did not start their sons early enough. To be an archer meant starting as a boy, then practising and practising until the chest was broad, the arm muscles huge and the arrow seemed to fly without the archer giving its aim any thought.

Jake shot his second bolt into the oak and swore horribly when it missed the mark. He looked at the bow. ‘Piece of shit,’ he said. ‘How close are we going to be?’

‘Close as we can get,’ Thomas said.

Jake sniffed. ‘If I can poke the bloody bow into the bastard’s belly I might not miss.’

‘Thirty, forty feet should be all right,’ Sam reckoned.

‘Aim at his crotch,’ Thomas encouraged them, ‘and we should gut him.’

‘It’ll be all right,’ Jake said, ‘three of us? One of us has got to skewer the bastard.’

‘In the shadows, lads,’ Thomas said, gesturing them deeper into the trees. He had seen Jeanette coming from the gate where the guards had inspected her pass then waved her on. She sat sideways on a small horse that Will Skeat had lent her and was accompanied by two grey-haired servants, a man and a woman, both of whom had grown old in her father’s service and now walked beside their mistress’s horse. If Jeanette had truly planned to ride to Louannec then such a feeble and aged escort would have been an invitation for trouble, but trouble, of course, was what she intended, and no sooner had she reached the trees than the trouble appeared as Sir Simon Jekyll emerged from the archway’s shadow, riding with two other men.

‘What if those two bastards stay close to him?’ Sam asked.

‘They won’t,’ Thomas said. He was certain of that, just as he and Jeanette had been certain that Sir Simon would follow her and that he would wear the expensive suit of plate he had stolen from her.

‘She’s a brave lass,’ Jake grunted.

‘She’s got spirit,’ Thomas said, ‘knows how to hate someone.’

Jake tested the point of a quarrel. ‘You and her?’ he asked Thomas. ‘Doing it, are you?’

‘No.’

‘But you’d like to. I would.’

‘I don’t know,’ Thomas said. He thought Jeanette beautiful, but Skeat was right, there was a hardness in her that repelled him. ‘I suppose so,’ he admitted.

‘Of course you would,’ Jake said, ‘be daft not to.’

Once Jeanette was among the trees Thomas and his companions trailed her, staying hidden and always conscious that Sir Simon and his two henchmen were closing quickly. Those three horsemen trotted once they reached the wood and succeeded in catching up with Jeanette in a place that was almost perfect for Thomas’s ambush. The road ran within yards of a clearing where a meandering stream had undercut the roots of a willow. The fallen trunk was rotted and thick with disc-like fungi. Jeanette, pretending to make way for the three armoured horsemen, turned into the clearing and waited beside the dead tree. Best of all there was a stand of young alders close to the willow’s trunk that offered cover to Thomas.

Sir Simon turned off the road, ducked under the branches and curbed his horse close to Jeanette. One of his companions was Henry Colley, the brutal yellow-haired man who had hurt Thomas so badly, while the other was Sir Simon’s slack-jawed squire, who grinned in expectation of the coming entertainment. Sir Simon pulled off the snouted helmet and hung it on his saddle’s pommel, then smiled triumphantly.

‘It is not safe, madame,’ he said, ‘to travel without an armed escort.’

‘I am perfectly safe,’ Jeanette declared. Her two servants cowered beside her horse as Colley and the squire hemmed Jeanette in place with their horses.

Sir Simon dismounted with a clank of armour. ‘I had hoped, dear lady,’ he said, approaching her, ‘that we could talk on our way to Louannec.’

‘You wish to pray to the holy Yves?’ Jeanette asked. ‘What will you beg of him? That he grants you courtesy?’

‘I would just talk with you, madame,’ Sir Simon said.

‘Talk of what?’

‘Of the complaint you made to the Earl of Northampton. You fouled my honour, lady.’

‘Your honour?’ Jeanette laughed. ‘What honour do you have that could be fouled? Do you even know the meaning of the word?’

Thomas, hidden behind the straggle of alders, was whispering a translation to Jake and Sam. All three crossbows were cocked and had their wicked little bolts lying in the troughs.

‘If you will not talk to me on the road, madame, then we must have our conversation here,’ Sir Simon declared.

‘I have nothing to say to you.’