По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

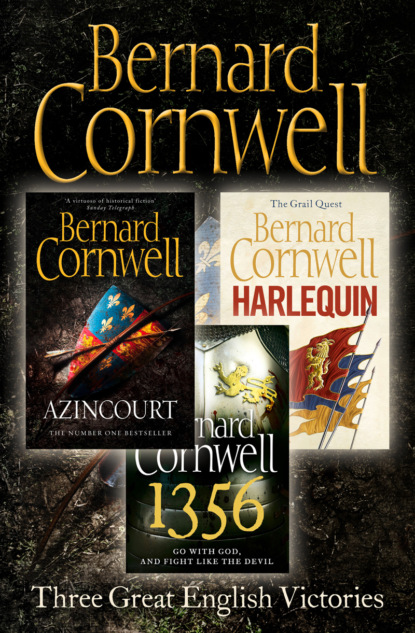

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘So you say,’ the priest said, ‘so you say.’ Charles was still crying and Jeanette jerked his hand hard in the hope of stilling him, but he just whined more. The clerk, head averted from the Duke, went from candle to candle. The scissors snipped, a puff of smoke would writhe for a heartbeat, then the flame would brighten and settle. Charles began crying louder.

‘His grace,’ the priest said, ‘does not like snivelling infants.’

‘He is hungry, father,’ Jeanette explained nervously.

‘You came with two servants?’

‘Yes, father,’ Jeanette said.

‘They can eat with the boy in the kitchens,’ the priest said, and snapped his fingers towards the candle-trimming clerk, who, abandoning his scissors on a rug, took the frightened Charles by the hand. The boy did not want to leave his mother, but he was dragged away and Jeanette flinched as the sound of his crying receded down the stairs.

The Duke, other than steepling his fingers, had not moved. He just watched Jeanette with an unreadable expression.

‘You say,’ the priest took up the questioning again, ‘that the English left you with nothing?’

‘They stole all I had!’

The priest flinched at the passion in her voice. ‘If they left you destitute, madame, then why did you not come for our help earlier?’

‘I did not wish to be a burden, father.’

‘But now you do wish to become a burden?’

Jeanette frowned. ‘I have brought his grace’s nephew, the Lord of Plabennec. Or would you rather that he grew up among the English?’

‘Do not be impertinent, child,’ the priest said placidly. The first clerk re-entered the room carrying the sack, which he emptied on the deerskins in front of the Duke’s table. The Duke gazed at the armour for a few seconds, then settled back in his high carved chair.

‘It is very fine,’ the priest declared.

‘It is most precious,’ Jeanette agreed.

The Duke peered again at the armour. Not a muscle of his face moved.

‘His grace approves,’ the priest said, then gestured with a long white hand and the clerk, who seemed to understand what was wanted without words, gathered up the sword and armour and carried them from the room.

‘I am glad your grace approves,’ Jeanette said, and dropped another curtsy. She had a confused idea that the Duke, despite her earlier words, had assumed the armour and sword were a gift, but she did not want to enquire. It could all be cleared up later. A gust of cold wind came through the arrow slits to bring spots of rain and to flicker the candles in wild shudders.

‘So what,’ the priest asked, ‘do you require of us?’

‘My son needs shelter, father,’ Jeanette said nervously. ‘He needs a house, a place to grow and learn to be a warrior.’

‘His grace is pleased to grant that request,’ the priest said.

Jeanette felt a great wash of relief. The atmosphere in the room was so unfriendly that she had feared she would be thrown out as destitute as she had arrived, but the priest’s words, though coldly stated, told her that she need not have worried. The Duke was taking his responsibility and she curtsied for a third time. ‘I am grateful, your grace.’

The priest was about to respond, but, to Jeanette’s surprise, the Duke held up one long white hand and the priest bowed. ‘It is our pleasure,’ the Duke said in an oddly high-pitched voice, ‘for your son is dear to us and it is our desire that he grows to become a warrior like his father.’ He turned to the priest and inclined his head, and the priest gave another stately bow then left the room.

The Duke stood and walked to the fire where he held his hands to the small flames. ‘It has come to our notice,’ he said distantly, ‘that the rents of Plabennec have not been paid these twelve quarters.’

‘The English are in possession of the domain, your grace.’

‘And you are in debt to me,’ the Duke said, frowning at the flames.

‘If you protect my son, your grace, then I shall be for ever in your debt,’ Jeanette said humbly.

The Duke took off his cap and ran a hand through his fair hair. Jeanette thought he looked younger and kinder without the hat, but his next words chilled her. ‘I did not want Henri to marry you.’ He stopped abruptly.

For a heartbeat Jeanette was struck dumb by his frankness. ‘My husband regretted your grace’s disapproval,’ she finally said in a small voice.

The Duke ignored Jeanette’s words. ‘He should have married Lisette of Picard. She had money, lands, tenants. She would have brought our family great wealth. In times of trouble wealth is a …’ he paused, trying to find the right word, ‘it is a cushion. You, madame, have no cushion.’

‘Only your grace’s kindness,’ Jeanette said.

‘Your son is my charge,’ the Duke said. ‘He will be raised in my household and trained in the arts of war and civilization as befits his rank.’

‘I am grateful.’ Jeanette was tired of grovelling. She wanted some sign of affection from the Duke, but ever since he had walked to the hearth he would not meet her eyes.

Now, suddenly, he turned on her. ‘There is a lawyer called Belas in La Roche-Derrien?’

‘Indeed, your grace.’

‘He tells me your mother was a Jewess.’ He spat the last word.

Jeanette gaped at him. For a few heartbeats she was unable to speak. Her mind was reeling with disbelief that Belas would say such a thing, but at last she managed to shake her head. ‘She was not!’ she protested.

‘He tells us, too,’ the Duke went on, ‘that you petitioned Edward of England for the rents of Plabennec?’

‘What choice did I have?’

‘And that your son was made a ward of Edward’s?’ the Duke asked pointedly.

Jeanette opened and closed her mouth. The accusations were coming so thick and fast she did not know how to defend herself. It was true that her son had been named a ward of King Edward’s, but it had not been Jeanette’s doing; indeed, she had not even been present when the Earl of Northampton made that decision, but before she could protest or explain the Duke spoke again.

‘Belas tells us,’ he said, ‘that many in the town of La Roche-Derrien have expressed satisfaction with the English occupiers?’

‘Some have,’ Jeanette admitted.

‘And that you, madame, have English soldiers in your own house, guarding you.’

‘They forced themselves on my house!’ she said indignantly. ‘Your grace must believe me! I did not want them there!’

The Duke shook his head. ‘It seems to us, madame, that you have given a welcome to our enemies. Your father was a vintner, was he not?’

Jeanette was too astonished to say anything. It was slowly dawning on her that Belas had betrayed her utterly, yet she still clung to the hope that the Duke would be convinced of her innocence. ‘I offered them no welcome,’ she insisted. ‘I fought against them!’

‘Merchants,’ the Duke said, ‘have no loyalties other than to money. They have no honour. Honour is not learned, madame. It is bred. Just as you breed a horse for bravery and speed, or a hound for agility and ferocity, so you breed a nobleman for honour. You cannot turn a plough-horse into a destrier, nor a merchant into a gentleman. It is against nature and the laws of God.’ He made the sign of the cross. ‘Your son is Count of Armorica, and we shall raise him in honour, but you, madame, are the daughter of a merchant and a Jewess.’

‘It is not true!’ Jeanette protested.