По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

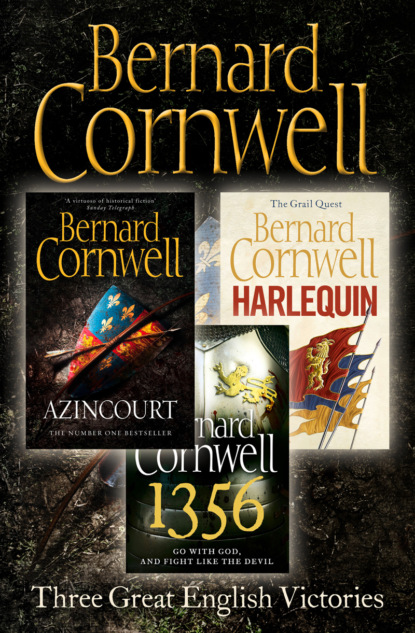

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Do not shout at me, madame,’ the Duke said icily. ‘You are a burden on me. You dare to come here, tricked out in fox fur, expecting me to give you shelter? What else? Money? I will give your son a home, but you, madame, I shall give you a husband.’ He walked towards her, his feet silent on the deerskin rugs. ‘You are not fit to be the Count of Armorica’s mother. You have offered comfort to the enemy, you have no honour.’

‘I –’ Jeanette began to protest again, but the Duke slapped her hard across the cheek.

‘You will be silent, madame,’ he commanded, ‘silent.’ He pulled at the laces of her bodice and, when she dared to resist, he slapped her again. ‘You are a whore, madame,’ the Duke said, then lost patience with the intricate cross-laces, retrieved the discarded scissors from the rug and used them to cut through the laces to expose Jeanette’s breasts. She was so astonished, stunned and horrified that she made no attempt to protect herself. This was not Sir Simon Jekyll, but her liege lord, the King’s nephew and her husband’s uncle. ‘You are a pretty whore, madame,’ the Duke said with a sneer. ‘How did you enchant Henri? Was it Jewish witchcraft?’

‘No,’ Jeanette whimpered, ‘please, no!’

The Duke unhooked his gown and Jeanette saw he was naked beneath.

‘No,’ she said again, ‘please, no.’

The Duke pushed her hard so that she fell on the bed. His face still showed no emotion – not lust, not pleasure, not anger. He hauled her skirts up, then knelt on the bed and raped her with no sign of enjoyment. He seemed, if anything, angry, and when he was done he collapsed on her, then shuddered. Jeanette was weeping. He wiped himself on her velvet skirt. ‘I shall take that experience,’ he said, ‘as payment of the missing rents from Plabennec.’ He crawled off her, stood and hooked the ermine edges of his gown. ‘You will be placed in a chamber here, madame, and tomorrow I shall give you in marriage to one of my men-at-arms. Your son will stay here, but you will go wherever your new husband is posted.’

Jeanette was whimpering on the bed. The Duke grimaced with distaste, then crossed the room and kneeled on the prie-dieu. ‘Arrange your gown, madame,’ he said coldly, ‘and compose yourself.’

Jeanette rescued enough of the cut laces to tie her bodice into place, then looked at the Duke through the candle flames. ‘You have no honour,’ she hissed, ‘you have no honour.’

The Duke ignored her. He rang a small handbell, then clasped his hands and closed his eyes in prayer. He was still praying when the priest and a servant came and, without a word, took Jeanette by her arms and walked her to a small room on the floor beneath the Duke’s chamber. They thrust her inside, shut the door and she heard a bolt slide into place on the far side. There was a straw-filled mattress and a stack of brooms in the makeshift cell, but no other furnishing.

She lay on the mattress and sobbed till her broken heart was raw.

The wind howled at the window and rain beat on its shutters, and Jeanette wished she was dead.

The city’s cockerels woke Thomas to a brisk wind and pouring rain that beat on the cart’s leaking cover. He opened the flap and sat watching the puddles spread across the cobbles of the inn yard. No message had come from Jeanette, nor, he thought, would there be one. Will Skeat had been right. She was as hard as mail and, now she was in her proper place – which, in this cold, wet dawn, was probably a deep bed in a room warmed by a fire tended by the Duke’s servants – she would have forgotten Thomas.

And what message, Thomas asked himself, had he been expecting? A declaration of affection? He knew that was what he wanted, but he persuaded himself he merely waited so Jeanette could send him the pass signed by the Duke, yet he knew he did not need a pass. He must just walk east and north, and trust that the Dominican’s robe protected him. He had little idea how to reach Flanders, but had a notion that Paris lay somewhere close to that region so he reckoned he would start by following the River Seine, which would lead him from Rennes to Paris. His biggest worry was that he would meet some real Dominican on the road, who would quickly discover Thomas had only the haziest notion of the brotherhood’s rules and no knowledge at all of their hierarchy, but he consoled himself that Scottish Dominicans were probably so far from civilization that such ignorance would be expected of them. He would survive, he told himself.

He stared at the rain spattering in the puddles. Expect nothing from Jeanette, he told himself, and to prove that he believed that bleak prophecy he readied his small baggage. It irked him to leave the mail coat behind, but it weighed too much, so he stowed it in the wagon, then put the three sheaves of arrows into a sack. The seventy-two arrows were heavy and their points threatened to tear open the sack, but he was reluctant to travel without the sheaves that were wrapped in hempen bowstring cord and he used one cord to tie his knife to his left leg where, like his money pouch, it was hidden by the black robe.

He was ready to go, but the rain was now hammering the city like an arrow storm. Thunder crackled to the west, the rain pelted on the thatch, poured off the roofs and overflowed the water butts to wash the inn’s nightsoil out of the yard. Midday came, heralded by the city’s rain-muffled bells, and still the city drowned. Wind-driven dark clouds wreathed the cathedral’s towers and Thomas told himself he would leave the moment the rain slackened, but the storm just became fiercer. Lightning flickered above the cathedral and a clap of thunder rocked the city. Thomas shivered, awed by the sky’s fury. He watched the lightning reflected in the cathedral’s great west window and was amazed by the sight. So much glass! Still it rained and he began to fear that he would be trapped in the cart till the next day. And then, just after a peal of thunder seemed to stun the whole city with its violence, he saw Jeanette.

He did not know her at first. He just saw a woman standing in the arched entrance to the inn’s yard with the water flowing about her shoes. Everyone else in Rennes was huddling in shelter, but this woman suddenly appeared, soaked and miserable. Her hair, which had been looped so carefully over her ears, hung lank and black down the sopping red velvet dress, and it was that dress that Thomas recognized, then he saw the grief on her face. He clambered out of the wagon.

‘Jeanette!’

She was weeping, her mouth distorted by grief. She seemed incapable of speaking, but just stood and cried.

‘My lady!’ Thomas said. ‘Jeanette!’

‘We must go,’ she managed to say, ‘we must go.’ She had used soot as a cosmetic about her eyes and it had run to make grey streaks down her face.

‘We can’t go in this!’ Thomas said.

‘We must go!’ she screamed at him angrily. ‘We must go!’

‘I’ll get the horse,’ Thomas said.

‘There’s no time! There’s no time!’ She plucked at his robe. ‘We must go. Now!’ She tried to tug him through the arch into the street.

Thomas pulled away from her and ran to the wagon where he retrieved his disguised bow and the heavy sack. There was a cloak of Jeanette’s there and he took that too and wrapped it about her shoulders, though she did not seem to notice.

‘What’s happening?’ Thomas demanded.

‘They’ll find me here, they’ll find me!’ Jeanette declared in a panic, and she pulled him blindly out of the tavern’s archway. Thomas turned her eastwards onto a crooked street that led to a fine stone bridge across the Seine and then to a city gate. The big gates were barred, but a small door in one of the gates was open and the guards in the tower did not care if some fool of a drenched friar wanted to take a madly sobbing woman out of the city. Jeanette kept looking back, fearing pursuit, but still did not explain her panic or her tears to Thomas. She just hurried eastwards, insensible to the rain, wind and thunder.

The storm eased towards dusk, by which time they were close to a village that had a poor excuse for a tavern. Thomas ducked under the low doorway and asked for shelter. He put coins on a table.

‘I need shelter for my sister,’ he said, reckoning that anyone would be suspicious of a friar travelling with a woman. ‘Shelter, food and a fire,’ he said, adding another coin.

‘Your sister?’ The tavern-keeper, a small man with a face scarred by the pox and bulbous with wens, peered at Jeanette, who was crouched in the tavern’s porch.

Thomas touched his head, suggesting she was mad. ‘I am taking her to the shrine of St Guinefort,’ he explained.

The tavern-keeper looked at the coins, glanced again at Jeanette, then decided the strange pair could have the use of an empty cattle byre. ‘You can put a fire there,’ he said grudgingly, ‘but don’t burn the thatch.’

Thomas lit a fire with embers from the tavern’s kitchen, then fetched food and ale. He forced Jeanette to eat some of the soup and bread, then made her go close to the fire. It took over two hours of coaxing before she would tell him the story, and telling it only made her cry again. Thomas listened, appalled.

‘So how did you escape?’ he asked when she was finished.

A woman had unbolted the room, Jeanette said, to fetch a broom. The woman had been astonished to see Jeanette there, and even more astonished when Jeanette ran past her. Jeanette had fled the citadel, fearing the soldiers would stop her, but no one had taken any notice of her and now she was running away. Like Thomas she was a fugitive, but she had lost far more than he. She had lost her son, her honour and her future.

‘I hate men,’ she said. She shivered, for the miserable fire of damp straw and rotted wood had scarcely dried her clothes. ‘I hate men,’ she said again, then looked at Thomas. ‘What are we going to do?’

‘You must sleep,’ he said, ‘and tomorrow we’ll go north.’

She nodded, but he did not think she had understood his words. She was in despair. The wheel of fortune that had once raised her so high had taken her into the utter depths.

She slept for a time, but when Thomas woke in the grey dawn he saw she was crying softly and he did not know what to do or say, so he just lay in the straw until he heard the tavern door creak open, then went to fetch some food and water. The tavern-keeper’s wife cut some bread and cheese while her husband asked Thomas how far he had to walk.

‘St Guinefort’s shrine is in Flanders,’ Thomas said.

‘Flanders!’ the man said, as though it was on the far side of the moon.

‘The family doesn’t know what else to do with her,’ Thomas explained, ‘and I don’t know how to reach Flanders. I thought to go to Paris first.’

‘Not Paris,’ the tavern-keeper’s wife said scornfully, ‘you must go to Fougères.’ Her father, she said, had often traded with the north countries and she was sure that Thomas’s route lay through Fougères and Rouen. She did not know the roads beyond Rouen, but was certain he must go that far, though to begin, she said, he must take a small road that went north from the village. It went through woods, her husband added, and he must be careful for the trees were hiding places for terrible men escaping justice, but after a few miles he would come to the Fougères highway, which was patrolled by the Duke’s men.

Thomas thanked her, offered a blessing to the house, then took the food to Jeanette, who refused to eat. She seemed drained of tears, almost of life, but she followed Thomas willingly enough as he walked north. The road, deep rutted by wagons and slick with mud from the previous day’s rain, twisted into deep woods that dripped with water. Jeanette stumbled for a few miles, then began to cry. ‘I must go back to Rennes,’ she insisted. ‘I want to go back to my son.’

Thomas argued, but she would not be moved. He finally gave in, but when he turned to walk south she just began to cry even harder. The Duke had said she was not a fit mother! She kept repeating the words, ‘Not fit! Not fit!’ She screamed at the sky. ‘He made me his whore!’ Then she sank onto her knees beside the road and sobbed uncontrollably. She was shivering again and Thomas thought that if she did not die of an ague then the grief would surely kill her.

‘We’re going back to Rennes,’ Thomas said, trying to encourage her.

‘I can’t!’ she wailed. ‘He’ll just whore me! Whore me!’ She shouted the words, then began rocking back and forwards and shrieking in a terrible high voice. Thomas tried to raise her up, tried to make her walk, but she fought him. She wanted to die, she said, she just wanted to die. ‘A whore,’ she screamed, and tore at the fox-fur trimmings of her red dress, ‘a whore! He said I shouldn’t wear fur. He made me a whore.’ She threw the tattered fur into the undergrowth.

It had been a dry morning, but the rain clouds were heaping in the east again, and Thomas was nervously watching as Jeanette’s soul unravelled before his eyes. She refused to walk, so he picked her up and carried her until he saw a well-trodden path going into the trees. He followed it to find a cottage so low, and with its thatch so covered with moss that at first he thought it was just a mound among the trees until he saw blue-grey woodsmoke seeping from a hole at its top. Thomas was worried about the outlaws who were said to haunt these woods, but it was beginning to rain again and the cottage was the only refuge in sight, so Thomas lowered Jeanette to the ground and shouted through the burrow-like entrance. An old man, white-haired, red-eyed and with skin blackened by smoke, peered back at Thomas. The man spoke a French so thick with local words and accent that Thomas could scarcely understand him, but he gathered the man was a forester and lived here with his wife, and the forester looked greedily at the coins Thomas offered, then said that Thomas and his woman could use an empty pig shelter. The place stank of rotted straw and shit, but the thatch was almost rainproof and Jeanette did not seem to care. Thomas raked out the old straw, then cut Jeanette a bed of bracken. The forester, once the money was in his hands, seemed little interested in his guests, but in the middle of the afternoon, when the rain had stopped, Thomas heard the forester’s wife hissing at him and, a few moments later, the old man left and walked towards the road, but without any of the tools of his trade; no axe, billhook or saw.

Jeanette was sleeping, exhausted, so Thomas stripped the dead clover plants from his black bow, unlashed the crosspiece and put back the horn tips. He strung the yew, thrust half a dozen arrows into his belt and followed the old man as far as the road, and there he waited in a thicket.