По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

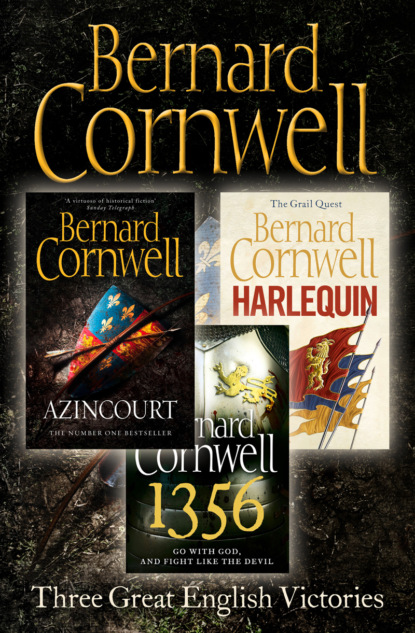

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Yes, Will,’ Thomas said meekly.

‘Don’t bloody ‘‘yes, Will’’ me,’ Skeat said. ‘What are you going to do with the few days you’ve got left to live?’

‘I don’t know.’

Skeat sniffed. ‘You could grow up, for a start, though there’s probably scant chance of that happening. Right, lad.’ He braced himself, taking charge. ‘I took your money from the chest, so here it is.’ He handed Thomas a leather pouch. ‘And I’ve put three sheaves of arrows in the lady’s cart and that’ll keep you for a few days. If you’ve got any sense, which you ain’t, then you’d go south or north. You could go to Gascony, but it’s a hell of a long walk. Flanders is closer and has plenty of English troops who’ll probably take you in if they’re desperate. That’s my advice, lad. Go north and hope Sir Simon never goes to Flanders.’

‘Thank you,’ Thomas said.

‘But how do you get to Flanders?’ Skeat asked.

‘Walk?’ Thomas suggested.

‘God’s bones,’ Will said, ‘but you’re a useless worm-eaten piece of lousy meat. Walk dressed like that and carrying a bow, and you might just as well just cut your own throat. It’ll be quicker than letting the French do it.’

‘You might find this useful,’ Father Hobbe intervened, and offered Thomas a black cloth bundle which, on unrolling, proved to be the robe of a Dominican friar. ‘You speak Latin, Tom,’ the priest said, ‘so you could pass for a wandering preacher. If anyone challenges you, say you’re travelling from Avignon to Aachen.’

Thomas thanked him. ‘Do many Dominicans travel with a bow?’ he asked.

‘Lad,’ Father Hobbe said sadly, ‘I can unbutton your breeches and I can point you down wind, but even with the Good Lord’s help I can’t piss for you.’

‘In other words,’ Skeat said, ‘work it out for yourself. You got yourself in this bloody mess, Tom, so you get yourself out. I enjoyed your company, lad. Thought you’d be useless when I first saw you and you weren’t, but you are now. But be lucky, boy.’ He held out his hand and Thomas shook it. ‘You might as well go to Guingamp with the Countess,’ Skeat finished, ‘and then find your own way, but Father Hobbe wants to save your soul first. God knows why.’

Father Hobbe dismounted and led Thomas into the roofless church where grass and weeds now grew between the flagstones. He insisted on hearing a confession and Thomas was feeling abject enough to sound contrite.

Father Hobbe sighed when it was done. ‘You killed a man, Tom,’ he said heavily, ‘and it is a great sin.’

‘Father –’ Thomas began.

‘No, no, Tom, no excuses. The Church says that to kill in battle is a duty a man owes to his lord, but you killed outside the law. That poor squire, what offence did he give you? And he had a mother, Tom; think of her. No, you’ve sinned grievously and I must give you a grievous penance.’

Thomas, on his knees, looked up to see a buzzard sliding between the thinning clouds above the church’s scorched walls. Then Father Hobbe stepped closer, looming above him. ‘I’ll not have you muttering paternosters, Tom,’ the priest said, ‘but something hard. Something very hard.’ He put his hand on Thomas’s hair. ‘Your penance is to keep the promise you made to your father.’ He paused to hear Thomas’s response, but the young man was silent. ‘You hear me?’ Father Hobbe demanded fiercely.

‘Yes, father.’

‘You will find the lance of St George, Thomas, and return it to England. That is your penance. And now,’ he changed into execrable Latin, ‘in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, I absolve you.’ He made the sign of the cross. ‘Don’t waste your life, Tom.’

‘I think I already have, father.’

‘You’re just young. It seems like that when you’re young. Life’s nothing but joy or misery when you’re young.’ He helped Thomas up from his knees. ‘You’re not hanging from a gibbet, are you? You’re alive, Tom, and there’s a deal of life in you yet.’ He smiled. ‘I have a feeling we shall meet again.’

Thomas made his farewells, then watched as Will Skeat collected Sir Simon Jekyll’s horse and led the hellequin eastwards, leaving the wagon and its small escort in the ruined village.

The leader of the escort was called Hugh Boltby, one of Skeat’s better men-at-arms, and he reckoned they would likely meet the enemy the next day somewhere close to Guingamp. He would hand the Countess over, then ride back to join Skeat. ‘And you’d best not be dressed as an archer, Tom,’ he added.

Thomas walked beside the wagon that was driven by Pierre, the old man who had been pressed by Sir Simon. Jeanette did not invite Thomas inside, indeed she pretended he did not exist, though next morning, after they had camped in an abandoned farm, she laughed at the sight of him dressed in the friar’s robe.

‘I’m sorry about what happened,’ Thomas said to her.

Jeanette shrugged. ‘It may be for the best. I probably should have gone to Duke Charles last winter.’

‘Why didn’t you, my lady?’

‘He hasn’t always been kind to me,’ she said wistfully, ‘but I think that might have changed by now.’ She had persuaded herself that the Duke’s attitude might have altered because of the letters she had sent to him, letters that would help him when he led his troops against the garrison at La Roche-Derrien. She also needed to believe the Duke would welcome her, for she desperately needed a safe home for her son, Charles, who was enjoying the adventure of riding in a swaying, creaking wagon. Together they would both start a new life in Guingamp and Jeanette had woken with optimism about that new life. She had been forced to leave La Roche-Derrien in a frantic hurry, putting into the cart just the retrieved armour, the sword and some clothes, though she had some money that Thomas suspected Will had given to her, but her real hopes were pinned on Duke Charles who, she told Thomas, would surely find her a house and lend her money in advance of the missing rents from Plabennec. ‘He is sure to like Charles, don’t you think?’ she asked Thomas.

‘I’m sure,’ Thomas said, glancing at Jeanette’s son, who was shaking the wagon’s reins and clicking his tongue in a vain effort to make the horse go quicker.

‘But what will you do?’ Jeanette asked.

‘I’ll survive,’ Thomas said, unwilling to admit that he did not know what he would do. Go to Flanders, probably, if he could ever reach there. Join another troop of archers and pray nightly that Sir Simon Jekyll never came his way again. As for his penance, the lance, he had no idea how he was to find it or, having found it, retrieve it.

Jeanette, on that second day of the journey, decided Thomas was a friend after all.

‘When we get to Guingamp,’ she told him, ‘you find somewhere to stay and I shall persuade the Duke to give you a pass. Even a wandering friar will be helped by a pass from the Duke of Brittany.’

But no friar ever carried a bow, let alone a long English war bow, and Thomas did not know what to do with the weapon. He was loath to abandon it, but the sight of some charred timbers in the abandoned farmhouse gave him an idea. He broke off a short length of blackened timber and lashed it crosswise to the unstrung bowstave so that it resembled a pilgrim’s cross-staff. He remembered a Dominican visiting Hookton with just such a staff. The friar, his hair cropped so short he looked bald, had preached a fiery sermon outside the church until Thomas’s father became tired of his ranting and sent him on his way, and Thomas now reckoned he would have to pose as just such a man. Jeanette suggested he tied flowers to the staff to disguise it further, and so he wrapped it with clovers that grew tall and ragged in the abandoned fields.

The wagon, hauled by a bony horse that had been plundered from Lannion, lurched and lumbered southwards. The men-at-arms became ever more cautious as they neared Guingamp, fearing an ambush of crossbow bolts from the woods that pressed close to the deserted road. One of the men had a hunting horn that he sounded constantly to warn the enemy of their approach and to signal that they came in peace, while Boltby had a strip of white cloth hanging from the tip of his lance. There was no ambush, but a few miles short of Guingamp they came in sight of a ford where a band of enemy soldiers waited. Two men-at-arms and a dozen crossbowmen ran forward, their weapons cocked, and Boltby summoned Thomas from the wagon. ‘Talk to them,’ he ordered.

Thomas was nervous. ‘What do I say?’

‘Give them a bloody blessing, for Christ’s sake,’ Boltby said, disgusted, ‘and tell them we’re here in peace.’

So, with a beating heart and a dry mouth, Thomas walked down the road. The black gown flapped awkwardly about his ankles as he waved his hands at the crossbowmen. ‘Lower your weapons,’ he called in French, ‘lower your weapons. The Englishmen come in peace.’

One of the horsemen spurred forward. His shield bore the same white ermine badge that Duke John’s men carried, though these supporters of Duke Charles had surrounded the ermine with a blue wreath on which fleur-de-lis had been painted.

‘Who are you, father?’ the horseman demanded.

Thomas opened his mouth to answer, but no words came. He gaped up at the horseman, who had a reddish moustache and oddly yellow eyes. A hard-looking bastard, Thomas thought, and he raised a hand to touch St Guinefort’s paw. Perhaps the saint inspired him, for he was suddenly possessed of devilment and began to enjoy playing a priest’s role. ‘I am merely one of God’s humbler children, my son,’ he answered unctuously.

‘Are you English?’ the man-at-arms demanded suspiciously. Thomas’s French was near perfect, but it was the French spoken by England’s rulers rather than the language of France itself.

Thomas again felt panic fluttering in his breast, but he bought time by making the sign of the cross, and as his hand moved so inspiration came to him. ‘I am a Scotsman, my son,’ he said, and that allayed the yellow-eyed man’s suspicions; the Scots had ever been France’s ally. Thomas knew nothing of Scotland, but doubted many Frenchmen or Bretons did either, for it was far away and, by all accounts, a most uninviting place. Skeat always said it was a country of bog, rock and heathen bastards who were twice as difficult to kill as any Frenchman. ‘I am a Scotsman,’ Thomas repeated, ‘who brings a kinswoman of the Duke out of the hands of the English.’

The man-at-arms glanced at the wagon. ‘A kinswoman of Duke Charles?’

‘Is there another duke?’ Thomas asked innocently. ‘She is the Countess of Armorica,’ he went on, ‘and her son, who is with her, is the Duke’s grandnephew and a count in his own right. The English have held them prisoner these six months, but by God’s good grace they have relented and set her free. The Duke, I know, will want to welcome her.’

Thomas laid on Jeanette’s rank and relationship to the Duke as thick as newly skimmed cream and the enemy swallowed it whole. They allowed the wagon to continue, and Thomas watched as Hugh Boltby led his men away at a swift trot, eager to put as much distance as possible between themselves and the crossbowmen. The leader of the enemy’s men-at-arms talked with Jeanette and seemed impressed by her hauteur. He would, he said, be honoured to escort the Countess to Guingamp, though he warned her that the Duke was not there, but was still returning from Paris. He was said to be at Rennes now, a city that lay a good day’s journey to the east.

‘You will take me as far as Rennes?’ Jeanette asked Thomas.

‘You want me to, my lady?’

‘A young man is useful,’ she said. ‘Pierre is old,’ she gestured at the servant, ‘and has lost his strength. Besides, if you’re going to Flanders then you will need to cross the river at Rennes.’

So Thomas kept her company for the three days that it took the painfully slow wagon to make the journey. They needed no escort beyond Guingamp for there was small danger of any English raiders this far east in Brittany and the road was well patrolled by the Duke’s forces. The countryside looked strange to Thomas, for he had become accustomed to rank fields, untended orchards and deserted villages, but here the farms were busy and prosperous. The churches were bigger and had stained glass, and fewer and fewer folk spoke Breton. This was still Brittany, but the language was French.