По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

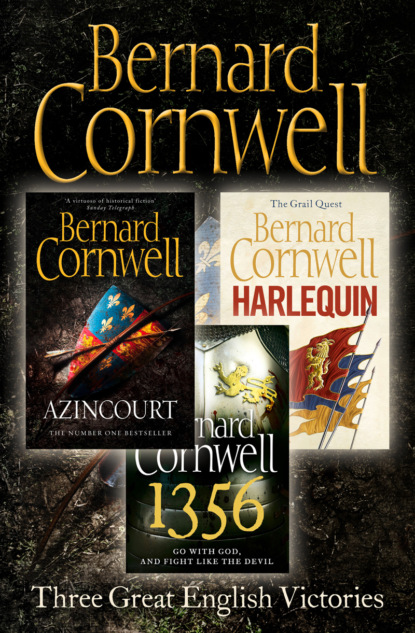

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Then you will find it easy enough to listen,’ he said, and reached up to haul her out of the saddle. She beat at his armoured gauntlets, but no resistance of hers could prevent him from dragging her to the ground. The two servants shrieked protests, but Colley and the squire silenced them by grabbing their hair, then pulling them out of the clearing to leave Jeanette and Sir Simon alone.

Jeanette had scrabbled backwards and was now standing beside the fallen tree. Thomas had raised his crossbow, but Jake pushed it down, for Sir Simon’s escort was still too near.

Sir Simon pushed Jeanette hard so that she sat down on the rotting trunk, then he took a long dagger from his sword belt and drove its narrow blade hard through Jeanette’s skirts so that she was pinned to the fallen willow. He hammered the knife hilt with his steel-shod foot to make sure it was deep in the trunk. Colley and the squire had vanished now and the noise of their horses’ hooves had faded among the leaves.

Sir Simon smiled, then stepped forward and plucked the cloak from Jeanette’s shoulders. ‘When I first saw you, my lady,’ he said, ‘I confess I thought of marriage. But you have been perverse, so I have changed my mind.’ He put his hands at her bodice’s neckline and ripped it apart, tearing the laces from their embroidered holes. Jeanette screamed as she tried to cover herself and Jake again held Thomas’s arm down.

‘Wait till he gets the armour off,’ Jake whispered. They knew the bolts could pierce mail, but none of the three knew how strong the plate armour would prove.

Sir Simon slapped Jeanette’s hands away. ‘There, madame,’ he said, gazing at her breasts, ‘now we can have discourse.’

Sir Simon stepped back and began to strip himself of the armour. He pulled off the plated gauntlets first, unbuckled the sword belt, then lifted the shoulder pieces on their leather harness over his head. He fumbled with the side buckles of the breast and back plates that were attached to a leather coat that also supported the rerebraces and vambraces that protected his arms. The coat had a chain skirt, which, because of the weight of the plate and ring mail, made it a struggle for Sir Simon to drag over his head. He staggered as he pulled at the heavy armour and Thomas again raised the crossbow, but Sir Simon was stepping back and forward as he tried to steady himself and Thomas could not be sure of his aim and so kept his finger off the trigger.

The armour-laden coat thumped onto the ground, leaving Sir Simon tousle-haired and bare-chested, and Thomas again put the crossbow stock into his shoulder, but now Sir Simon sat down to strip off the cuisses, greaves, poleyns and boots, and he sat in such a way that his armoured legs were towards the ambush and kept getting in the way of Thomas’s aim. Jeanette was struggling with the knife, scared out of her wits that Thomas had not stayed close, but tug as she might the dagger would not move.

Sir Simon pulled off the sollerets that covered his feet, then wriggled out of the leather breeches to which the leg plates were attached. ‘Now, madame,’ he said, standing whitely naked, ‘we can talk properly.’

Jeanette heaved a last time at the dagger, hoping to plunge it into Sir Simon’s pale belly, and just then Thomas pulled his trigger.

The bolt scraped across Sir Simon’s chest. Thomas had aimed at the knight’s groin, hoping to send the short arrow deep into his belly, but the bolt had grazed one of the whiplike alder boughs and been deflected. Blood streaked on Sir Simon’s skin and he dropped to the ground so fast that Jake’s bolt whipped over his head. Sir Simon scrambled away, going first to his discarded armour. Then he realized he had no time to save the plate and so he ran for his horse, and it was then that Sam’s bolt caught him in the flesh of his right thigh so that he yelped, half fell and decided there was no time to rescue his horse either and just limped naked and bleeding into the woods. Thomas loosed a second bolt that rattled past Sir Simon to whack into a tree, and then the naked man vanished. Thomas swore. He had meant to kill, but Sir Simon was all too alive.

‘I thought you weren’t here!’ Jeanette said as Thomas appeared. She was clutching her torn clothing to her breasts.

‘We missed the bastard,’ Thomas said angrily. He heaved the dagger free of her skirts while Jake and Sam thrust the armour into two sacks. Thomas threw down the crossbow and took his own black bow from his shoulder. What he should do now, he thought, was track Sir Simon through the trees and kill the bastard. He could pull out the white-feathered arrow and put a crossbow bolt into the wound so that whoever found him would believe that bandits or the enemy had killed the knight.

‘Search the bastard’s saddle pouches,’ he told Jake and Sam. Jeanette had tied the cloak round her neck and her eyes widened as she saw the gold pour from the pouches. ‘You’re going to stay here with Jake and Sam,’ Thomas told her.

‘Where are you going?’ she asked.

‘To finish the job,’ Thomas said grimly. He loosed the laces of his arrow bag and dropped one crossbow bolt in among the longer arrows. ‘Wait here,’ he told Jake and Sam.

‘I’ll help you,’ Sam said.

‘No,’ Thomas insisted, ‘wait here and look after the Countess.’ He was angry with himself. He should have used his own bow from the start and simply removed the telltale arrow and shot a bolt into Sir Simon’s corpse, but he had fumbled the ambush. But at least Sir Simon had fled westwards, away from his two men-at-arms, and he was naked, bleeding and unarmed. Easy prey, Thomas told himself as he followed the blood drops among the trees. The trail went west and then, as the blood thinned, southwards. Sir Simon was obviously working his way back towards his companions and Thomas abandoned caution and just ran, hoping to cut the fugitive off. Then, bursting through some hazels, he saw Sir Simon, limping and bent. Thomas pulled the bow back, and just then Colley and the squire came into view, both with swords drawn and both spurring their horses at Thomas. He switched his aim to the nearest and loosed without thinking. He loosed as a good archer should, and the arrow went true and fast, smack into the mailed chest of the squire, who was thrown back in his saddle. His sword dropped to the ground as his horse swerved hard to its left, going in front of Sir Simon.

Colley wrenched his reins and reached for Sir Simon, who clutched at his outstretched hand and then half ran and was half carried away into the trees. Thomas had dragged a second arrow from the bag, but by the time he loosed it the two men were half hidden by trees and the arrow glanced off a branch and was lost among the leaves.

Thomas swore. Colley had stared straight at Thomas for an instant. Sir Simon had also seen him and Thomas, a third arrow on his string, just stared at the trees as he understood that everything had just fallen apart. In one instant. Everything.

He ran back to the clearing by the stream. ‘You’re to take the Countess to the town,’ he told Jake and Sam, ‘but for Christ’s sake go carefully. They’ll be searching for us soon. You’ll have to sneak back.’

They stared at him, not understanding, and Thomas told them what had happened. How he had killed Sir Simon’s squire, and how that made him both a murderer and a fugitive. He had been seen by Sir Simon and by the yellow-haired Colley, and they would both be witnesses at his trial and celebrants at his execution.

He told Jeanette the same in French. ‘You can trust Jake and Sam,’ he told her, ‘but you mustn’t be caught going home. You have to go carefully!’

Jake and Sam argued, but Thomas knew well enough what the consequences of the killing arrow were. ‘Tell Will what happened,’ he told them. ‘Blame it all on me and say I’ll wait for him at Quatre Vents.’ That was a village the hellequin had laid waste south of La Roche-Derrien. ‘Tell him I’d like his advice.’

Jeanette tried to persuade him that his panic was unnecessary. ‘Perhaps they did not recognize you?’ she suggested.

‘They recognized me, my lady,’ Thomas said grimly. He smiled ruefully. ‘I am sorry, but at least you have your armour and sword. Hide them well.’ He pulled himself into Sir Simon’s saddle. ‘Quatre Vents,’ he told Jake and Sam, then spurred southwards through the trees.

He was a murderer, a wanted man and a fugitive, and that meant he was any man’s prey, alone in the wilderness made by the hellequin. He had no idea what he should do or where he could go, only that if he was to survive then he must ride like the devil’s horseman that he was.

So he did.

Quatre Vents had been a small village, scarce larger than Hookton, with a gaunt barn-like church, a cluster of cottages where cows and people had shared the same thatched roofs, a water mill, and some outlying farms crouched in sheltered valleys. Only the stone walls of the church and mill were left now, the rest was just ashes, dust and weeds. The blossom was blowing from the untended orchards when Thomas arrived on a horse sweated white by its long journey. He released the stallion to graze in a well-hedged and overgrown pasture, then took himself into the woods above the church. He was shaken, nervous and frightened, for what had seemed like a game had twisted his life into darkness. Not a few hours before he had been an archer in England’s army and, though his future might not have appealed to the young men with whom he had rioted in Oxford, Thomas had been certain he would at least rise as high as Will Skeat. He had imagined himself leading a band of soldiers, becoming wealthy, following his black bow to fortune and even rank, but now he was a hunted man. He was in such panic that he began to doubt Will Skeat’s reaction, fearing that Skeat would be so disgusted at the failure of the ambush that he would arrest Thomas and lead him back to a rope-dancing end in La Roche-Derrien’s marketplace. He worried that Jeanette would have been caught going back to the town. Would they charge her with murder too? He shivered as night fell. He was twenty-two years old, he had failed utterly, he was alone and he was lost.

He woke in a cold, drizzling dawn. Hares raced across the pasture where Sir Simon Jekyll’s destrier cropped the grass. Thomas opened the purse he kept under his mail coat and counted his coins. There was the gold from Sir Simon’s saddle pouch and his own few coins, so he was not poor, but like most of the hellequin he left the bulk of his money in Will Skeat’s keeping; even when they were out raiding, there were always some men left in La Roche-Derrien to keep an eye on the hoard. What would he do? He had a bow and some arrows, and perhaps he could walk to Gascony, though he had no idea how far that was, but at least he knew there were English garrisons there who would surely welcome another trained archer. Or perhaps he could find a way to cross the Channel? Go home, find another name, start again – except he had no home. What he must never do was find himself within a hanging rope’s distance of Sir Simon Jekyll.

The hellequin arrived shortly after midday. The archers rode into the village first, followed by the men-at-arms, who were escorting a one-horse wagon that had wooden hoops supporting a flapping cover of brown cloth. Father Hobbe and Will Skeat rode beside the wagon, which puzzled Thomas, for he had never known the hellequin use such a vehicle before. But then Skeat and the priest broke away from the men-at-arms and spurred their horses towards the field where the stallion grazed.

The two men stopped by the hedge, and Skeat cupped his hands and shouted towards the woods, ‘Come on out, you daft bastard!’ Thomas emerged very sheepishly, to be greeted with an ironic cheer from the archers. Skeat regarded him sourly. ‘God’s bones, Tom,’ he said, ‘but the devil did a bad thing when he humped your mother.’

Father Hobbe tutted at Will’s blasphemy, then raised a hand in blessing. ‘You missed a fine sight, Tom,’ he said cheerfully: ‘Sir Simon coming home to La Roche, half naked and bleeding like a stuck pig. I’ll hear your confession before we go.’

‘Don’t grin, you stupid bastard,’ Skeat snapped. ‘Sweet Christ, Tom, but if you do a job, do it proper. Do it proper! Why did you leave the bastard alive?’

‘I missed.’

‘Then you go and kill some poor bastard squire instead. Sweet Christ, but you’re a goddamn bloody fool.’

‘I suppose they want to hang me?’ Thomas asked.

‘Oh no,’ Skeat said in feigned surprise, ‘of course not! They want to feast you, hang garlands round your neck and give you a dozen virgins to warm your bed. What the hell do you think they want to do with you? Of course they want you dead and I swore on my mother’s life I’d bring you back if I found you alive. Does he look alive to you, father?’

Father Hobbe examined Thomas. ‘He looks very dead to me, Master Skeat.’

‘He bloody deserves to be dead, the daft bastard.’

‘Did the Countess get safe home?’ Thomas asked.

‘She got home, if that’s what you mean,’ Skeat said, ‘but what do you think Sir Simon wanted the moment he’d covered up his shrivelled prick? To have her house searched, Tom, for some armour and a sword that were legitimately his. He’s not such a daft fool; he knows you and she were together.’ Thomas cursed and Skeat repeated the blasphemy. ‘So they pressed her two servants and they admitted the Countess planned everything.’

‘They did what?’ Thomas asked.

‘They pressed them,’ Skeat repeated, which meant that the old couple had been put flat on the ground and had stones piled on their chests. ‘The old girl squealed everything at the first stone, so they were hardly hurt,’ Skeat went on, ‘and now Sir Simon wants to charge her ladyship with murder. And naturally he had her house searched for the sword and armour, but they found nowt because I had them and her hidden well away, but she’s still as deep in the shit as you are. You can’t just go about sticking crossbow bolts into knights and slaughtering squires, Tom! It upsets the order of things!’

‘I’m sorry, Will,’ Thomas said.

‘So the long and the brief of it,’ Skeat said, ‘is that the Countess is seeking the protection of her husband’s uncle.’ He jerked a thumb at the cart. ‘She’s in that, together with her bairn, two bruised servants, a suit of armour and a sword.’

‘Sweet Jesus,’ Thomas said, staring at the cart.

‘You put her there,’ Skeat growled, ‘not Him. And I had the devil’s own business keeping her hid from Sir Simon. Dick Totesham suspects I’m up to no good and he don’t approve, though he took my word in the end, but I still had to promise to drag you back by the scruff of your miserable neck. But I haven’t seen you, Tom.’

‘I’m sorry, Will,’ Thomas said again.

‘You bloody well should be sorry,’ Skeat said, though he was exuding a quiet satisfaction that he had managed to clean up Thomas’s mess so efficiently. Jake and Sam had not been seen by Sir Simon or his surviving man-at-arms, so they were safe, Thomas was a fugitive and Jeanette had been safely smuggled out of La Roche-Derrien before Sir Simon could make her life into utter misery. ‘She’s travelling to Guingamp,’ Skeat went on, ‘and I’m sending a dozen men to escort her and God only knows if the enemy will respect their flag of truce. If I had a lick of bloody sense I’d skin you alive and make a bow-cover out of your hide.’