По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

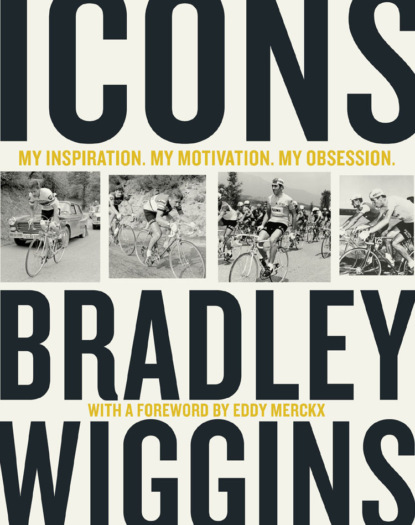

Icons: My Inspiration. My Motivation. My Obsession.

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Merckx rode for the short-lived Faemino-Faema team between 1968 and 1970. The team mostly comprised Belgian riders, with a few Italians.

FOREWORD (#ulink_4ae6c8af-f116-517e-bcf2-e66cb30719be)

FOOTBALL WAS MY FIRST LOVE, and like most kids from Brussels I was an Anderlecht fan. However, one day I discovered the great Stan Ockers, and fell in love with cycling.

Stan was a hero to me, just as he was to many Belgians. In 1955 he won the World Championships, Flèche Wallonne and Liège–Bastogne–Liège, but in general he tended to lose more races than he won. He was popular because he was a great rider, but most of all I think because he was a great sportsman. I liked to pretend I was him as I rode my bike, but then in 1956 he died following a crash on the track at Antwerp, his home town. I was only 11 at the time, but his death broke my heart.

Ultimately, Stan was the reason I started racing. I went on to win 525 professional races, so I guess you could say that he changed the course of cycling history.

The point is that we are all dreamers. We’re all fans first and foremost, because if we weren’t we wouldn’t become sportsmen. I started out pretending to be Stan, and through him I learned about Rik Van Steenbergen, Briek Schotte and Fausto Coppi. Eventually I became a professional cyclist, and I wanted to emulate Coppi and Jacques Anquetil by winning the Tour de France and breaking the Hour Record.

Brad’s story is more or less the same. He started out watching Miguel Induráin, and decided he wanted to understand cycling history for himself. That led him to me, to the Tour de France, to the Hour Record and eventually to our friendship.

We were lucky enough to be blessed with the talent to win bike races, but in reality we were no different to millions of starry-eyed kids down the years. History repeats itself in cycling, and I know for a fact that there are thousands of young British guys who took up cycling because of Brad. That’s the way it rolls in cycling, and the way it always was.

Enjoy the ride …

In among all the jerseys in my collection, Eddy’s gloves mean a hell of a lot.

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_695a7272-8278-5b97-8771-93e653733879)

CYCLING SEEMS TO ATTRACT A LOT OF COLLECTORS, probably because it’s always been so important historically and culturally. You could say it’s just a sport, but the bike itself still plays a big role in the way human civilisations think and act. You only have to look at places like Holland and China to see this, and to understand that, long after fossil-fuel cars have disappeared, the humble bike will still be around. I genuinely don’t think there’s any one single invention that has been healthier for the human mind and body, so while it is ‘just’ a sport, for many people it’s also a way of life and of living.

Bike racing is unique among mainstream sports because its development was totally organic. It didn’t have to be ‘invented’ like the others, because Europeans have been learning to cycle for well over 100 years. Going fast on a pushbike is the most natural thing in the world, and organised racing is just an extension of that.

As a professional sport it has two special characteristics. The first is that it’s free to watch; the second, that it goes to its public and not vice versa. What I mean by this is that there are no filters – the riders are literally within touching distance, and the public are intrinsic to the spectacle. It’s much easier to watch cycling on TV, and actually being there means you’re only going to see a tiny fraction of the action. The feeling a bike race generates, however, is electric, and I think that’s one of the reasons people stand by the roadside for hours waiting for what often amounts to a few moments. The key is its sheer intimacy, and that’s why the sport is so closely linked to its fans’ identity. Of course, there are millions of hobby cyclists, but there are also people like me, for whom it’s all-consuming.

Thinking I’m Joey McLoughlin at Herne Hill in 1988.

I think all of the above – and certainly some complex anthropological stuff – explains the collecting thing. People go nuts for bidons, but also musettes, caps, race numbers, race direction signs and accreditation paraphernalia. There are guys with massive collections of postcards, cigarette cards, autographs, race books, photographs, miniatures, badges and magazines. There are also people who collect specific brands, especially exotic Italian ones like Campagnolo, Bianchi and Colnago. There are guys who collect stuff from specific races, typically the Giro and the Tour, and of course there are collectors of the bikes themselves. There are loads of personal museums, and I know of a chap in Italy who has over 300 perfectly restored professional racing cycles. He keeps them in a massive house he rents halfway up a mountain, and it has more security than Fort Knox. That guy also has three ex-wives, but such is life …

Eastway 1995, in the exact spot on which the finish line of the velodrome now sits.

For people like me, however, it’s all about the jerseys.

Football and cricket teams get a trophy if they win, or an urn full of ashes. In track and field they get a medal. In golf the winner of the Masters gets a green jacket, and in World Series baseball the champions get a ring. I’m sure they’re fantastic things, but they’re basically inanimate. They’re not used in competition, and there’s nothing used or worn in any of these sports that distinguishes the champions from the mere mortals. Diego Maradona and Michael Jordan had a number on their backs, but essentially they wore the same kit as the others, as did individual sporting greats such as Borg, Bolt and Ali.

Like all great sportsmen, champion cyclists come and go. So do their sponsors, but their jerseys remain. Over the years they accumulate value, because through them we learn the history of our sport and, as cycling people, of ourselves – they’re also a mirror of the times, on our habits and our culture. First, the sponsors were the bike manufacturers and then, after the war, companies that made leisure items and consumer goods. It started with toothpaste, because as we became wealthier dental hygiene became more affordable. Next came things like aperitifs, and status symbols such as domestic appliances. They were followed by fitted kitchens, televisions, colour televisions, ice cream for the kids. Then cars, travel agents, video recorders, telecoms … As you work through the collection, it becomes apparent that the evolution of the brand logos is of as much interest and importance as that of the shirts themselves. Cycling jerseys not only tell us the story of cycling and of cyclists, but also, if we look closely, of the continent.

Then, of course, there are the leaders’ jerseys and champion’s jersey. They are the cycling icons, and there’s a small army of people like me who collect them. Of course, what we’re really collecting is proximity. Through the jerseys we feel closer to the champions who wore them, because they’re the people who wrote the history of the thing we love.

This book constitutes a thank-you note to 21 of them and, overwhelmingly, a love letter to the sport of cycling.

I hope you enjoy it.

Me with 1980 and 1986 world champion Tony Doyle. Great Flintstones’ shorts!

(#ulink_90bb1b19-d02a-574b-ab01-50eff3acac91)

One of my first real cycling memories is the final-day time trial of the 1989 Tour de France. I was nine, we were round at my nan’s house and my grandad was watching the race as usual. I wasn’t much interested in Laurent Fignon and Greg LeMond – in truth I barely knew who they were – but I very well remember being struck by the visual elements. Fignon’s ponytail, his yellow jersey and disc wheels, LeMond’s fluorescent kit, strange handlebars and that futuristic helmet he had … I didn’t understand the magnitude of what I was witnessing, but aesthetically it was spectacular.

Like most inner-city London kids, however, I was a football fan. The sportsmen I identified with had names like Adams, Merson and Thomas, not Chioccioli, Delgado and Van Hooydonck. The Arsenal players used to drink in the local pub after the game, and most of them were Londoners. Tottenham had Gary Lineker and Paul Gascoigne in their side at the time, and Lineker lived quite close by in St John’s Wood. Me and my mates saw him walking back from the shop with a pint of milk one day, and followed him to this house in Abbey Gardens. Once we knew where he lived we just knocked on the door and asked his wife if he was in, in pretty much the same way we used to ask one another’s mums. She sent us on our way with an autographed publicity card each, but I’ve an idea the whole episode is quite illustrative. Famous sportsmen seemed more accessible, and I don’t think there were so many filters between them and ‘normal people’ back then.Ultimately, though, it didn’t matter anyway. By the summer of 1992 Lineker was playing in Japan, and my sporting world paradigm was about to be turned completely on its head.

The king of his generation.

BACK THEN GREAT BRITAIN WASN’T WINNING A GREAT DEAL at the Olympics, and it wasn’t winning at all at Olympic cycling. As such, when Chris Boardman dominated the pursuit on his futuristic Lotus bike at the 1992 games in Barcelona, it was front-page news. Here was a British cyclist using a marvel of engineering made by a quintessentially British company – and conquering the world. The following morning I had to take the Tube across London to play football, and when I got to the station I noticed that the news stands were full of it. For better or for worse (!), British cyclists often occupy the front pages nowadays, but back then it was unheard of.

Chris on ‘that bike’ at the 1992 Olympics.

Chris had captured the public imagination, and that included me as well. I mentioned it to my mum, and she said I ought to think about giving cycling a go. I had a racing bike from Halfords, and she reasoned that I might be quite good at it. My dad had been a professional bike rider, so I had the genes if nothing else. Then if I was talented I’d have a much better chance of making it, because everyone else wanted to be a footballer. Besides, she still knew a few people in cycling and said it was a great sport. I saw no reason not to try, and so off we went to Hillingdon, where we met a guy named Stuart Benstead. He’d brought my dad over from Australia in the 1970s, and the two of them had lived together for a time. He ran the Archer Road Club, and he remembered me as a toddler. He said I ought to join the club, and before I knew it I was racing.

Truth be told it was a pretty chastening experience, at least initially. I was a 12-year-old doing under-16 races, so the others were much bigger and stronger than me. Most Friday nights I’d get an absolute pasting, then shuffle off home with my tail between my legs. Somehow, though, cycling’s perverse logic started to take hold of me. The worse it got, the more I seemed to like it and the more I resolved to get better at it.

By the following spring I was half decent. I was still getting shelled out on the climbs, and the others were much more committed than I was. They used to train, where I’d pretty much just turn up and race. I’d started to look forward to the races, however, and to take an interest in the gear. By then cable TV had come to London, and Eurosport showed quite a lot of cycling.

Cornering in Bury St Edmunds in 1996.

1993 Belgian champion’s jersey

This was the point at which I began to understand that cycling mattered a lot in Europe, that it was very much a mainstream sport. I remember looking forward to Milan–San Remo, as well as the feeling of disappointment when I heard it wasn’t going to be televised. I had to wait until the Thursday, when Cycling Weekly came out, to discover that an Italian named Maurizio Fondriest had won it. That waiting seems incredible now, because you can get the results of the races within seconds, but that’s the way it was back then. It really was a different world.

The first live road race I watched was the Tour of Flanders. Hitherto I had really no idea that so many people would come out to watch a bike race, but there seemed to be seas of them. Nor had I any real appreciation of just how fast it all was and how ferociously the professionals raced. Johan Museeuw won it in this beautiful tricoloured jersey – red, black and yellow – and Mum told me he got to wear it because he was the Belgian national champion, which I thought was a really wicked idea. She explained some of the rituals around De Ronde, as the Tour of Flanders is known in Flemish. She said it was the highlight of the year for Flemish people, almost irrespective of whether or not they were cycling fans. She also told me that Museeuw would be like the king over there. He was a Flemish rider wearing the national champion’s jersey to win Flanders, and nothing came close to that as regards performance or prestige. Thus Museeuw, the ‘Lion of Flanders’, became my first cycling hero, and so began the long and winding road that has been my journey in bike racing.

It’s impossible to exaggerate how good Museeuw was, and how aggressively he rode. Almost any article you read about him at the time included words like ‘warrior’ or ‘fighter’ somewhere along the line. These were – and remain – the oldest clichés in the cycling book, but they fitted him like a glove. Other cyclists were more stylish, but nobody was ever as brave, nor looked as purposeful. The Flemish people identified with him because he was the identikit classics rider, the living embodiment of their cycling tradition. Where Boardman had been about method, science and discipline, Museeuw was an old-school blood-and-snot cyclist like no other.

A few years later, when I was 16, I went to Belgium for a week with my mum, stepdad and half-brother. We went to watch the classics, and I saw Museeuw in the flesh. I’ve italicised that for dramatic effect, but only because dramatic is precisely what it was, at least for me. My mum still has a load of photographs she took that week. Some of them are a bit bizarre, but collectively they tell an unforgettable story. Most of them are of my eight-year-old brother, standing with the champions at the start of the Tour of Flanders. Like most 16-year-olds I was too cool for school, so I’d send him up to them instead. In some ways he was acting as a sort of proxy for me, because I didn’t want to come across as the smitten, star-struck teenager that I was. I feigned indifference and pretended to take it all in my stride, but in reality I was just overcome by the whole thing. Maybe I was afraid they might reject me or some such, but the long and the short of it was that metaphorically I was wetting my pants. I was at the Tour of Flanders, but I wasn’t of the Tour of Flanders. I was trying desperately hard to pretend it was just a normal day at the races, but the reality was I was all over the place. I’d been looking forward to the moment for years, but now that it had arrived it was too much for me to compute.

During the race we went to the feed, and I remember grabbing all the musettes as they threw them away. I think I got about 20 of them from that one race – I had the others scrambling about for them as well – and the Rabobank one had a rice cake in it. I had to decide whether to eat it or keep it as a souvenir, and I can assure you that was quite a decision. I ate it in the end, and then we went to the second feed in Zottegem. We scrounged a load of caps from the soigneurs, watched the riders come through again, and then made for the bar to watch the last 60 kilometres on TV.

At a certain point this guy walked in with long, curly, strawberry-blond hair. I realised it was Eric Vanderaerden, and I knew all about him. By then I’d amassed the world’s largest collection of cycling videotapes, and one of them showed him winning the race in 1985. Now he was getting towards the end of his career and he’d climbed off, got changed and just walked into the bar with his soigneur. He wasn’t one of my favourites, but I was blown away all the same. I was in the same bar as Eric Vanderaerden!

Anyway, Michele Bartoli attacked on the Muur van Geraardsbergen and time-trialled to the win. He was a new star and I didn’t know much about him, but after the race we went and stood around the team buses waiting for Museeuw to emerge. When he came out he didn’t look happy – he’d been going for a third Ronde and had been undone by some sort of mechanical failure – but he had to walk 100 metres across the car park to get to his dad’s car. I didn’t dare speak to him, but I got close enough to be able to delude myself that I’d ‘met’ him. What I’d actually done was walk alongside him for a few steps, and my mum has a grainy old photo to prove it.

1996 world champion’s jersey

The first time I raced against Johan would have been the 2002 Tour of Flanders. Actually, no, strike that. Technically I was taking part in the same race as Johan Museeuw, but I wasn’t racing against him as such. He was in a different stratosphere as a bike rider, and my abiding memory of that race is thinking, ‘Hang on a minute. That’s Johan Museeuw and I’m doing the same race as him!’ Beyond that I just remember the size of a) his calves and b) the gear he was able to turn.

There was a big fight to get to the Molenberg in front, and I think it was there that my education as a professional road cyclist began in earnest. People were just pushing me out of their wheels all the time, and I didn’t have the fight in me to do anything about it. If one of them asked me what I was doing or tried to shunt me into the gutter, I’d find myself apologising to them, in essence just capitulating. I was there, but I never felt like I’d earned the right to be there.

The Wednesday after Flanders it was Gent–Wevelgem. It was quite windy that day, and I decided not to allow myself to be pushed around. One of my jobs was to make sure I took my team-mates up to the front before the Kemmelberg, and I was determined I’d accomplish it. The Acqua & Sapone team were there, and their leader was Mario Cipollini, a big, macho, alpha-male Tuscan. He’d won San Remo and was favourite for the race. So I checked that my team-mates were on the wheel, and started making my way up the side of the road. Eventually I came up alongside the Italians, by now feeling quite good about myself because I felt I was doing the job that I was asked to do. The problem was that Cipollini was looking across at me with something approaching total contempt. Unbeknownst to me my colleagues had just sat up, and like a dick I’d ridden to the front of Gent–Wevelgem on my own. Cipo obviously assumed I was French – I had a Française des Jeux jersey on – and he turned to the rest of his team and said something along the lines of, ‘Look at this French wanker!’

Museeuw in the 1993 Tour of Flanders, his first win in the race.

I’d thought I was being a real pro, but now these Italians were laughing at me, quite literally. I had to creep back to my place at the back of the group, and I felt like a wimpering dog. Then we hit a crosswind, then I went out the back, and then I climbed off at the first feed. It was pretty embarrassing, to say the least. Cipo could make you feel really small. I hated him for that at the time, but cycling was much more hierarchical back then. People like me didn’t dare go near people like him and Museeuw, because you had to serve your apprenticeship first. The idea that I might try to converse with them never even occurred to me, and I reasoned that Museeuw wouldn’t have known who I was anyway. I was a nobody, and he was far too busy trying to win the bike races I was nominally competing in. He retired in 2004, blissfully unaware of the fact that he’d been my boyhood idol. How, realistically, could it have been otherwise, given that I hadn’t managed to utter a word to him?

You live and learn, and eventually I got pretty good at it. I had a long career, and towards the end of it I began a sort of sentimental journey. In the spring of 2015 I was doing an interview with the Belgian press. I was about to take part in my final Tour of Flanders, and they asked me about my cycling upbringing. I started telling them the story of how Museeuw’s 1993 Flanders had been the first race I’d really watched, and it got back to him. He speaks some English, and he sent me a message on Instagram. It was something like, ‘Good luck and thanks for what you said about me.’ I replied, and he told me that his 15-year-old son, Stefano, was a big fan of mine. He then asked if it would be OK for them to come and meet me before Paris–Roubaix, and I said that yes, of course it would.