По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

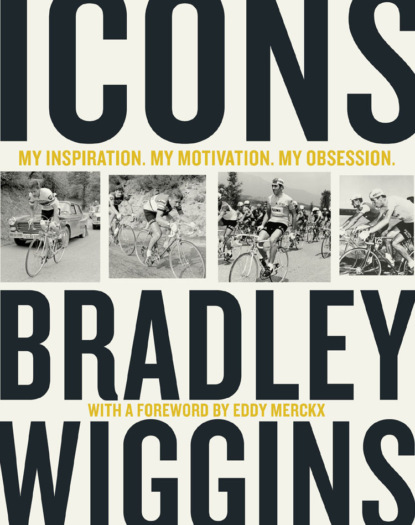

Icons: My Inspiration. My Motivation. My Obsession.

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Then I started to panic, because Johan Museeuw was coming to meet me.

So next thing I was having a massage after a training ride, and Servais Knaven, our DS, came up. He said, ‘Johan’s downstairs in the lobby waiting for you.’ He was early, but I started panicking because I was keeping the great Johan Museeuw waiting. I asked Servais, ‘What am I supposed to say to him?’ Servais thought that was quite funny. He said, ‘How should I know? Just talk to him! He’s only human!’

Eventually I went down, and I was that teenager all over again. I was basically 16, but by now Johan was almost 50. He has this gentle, soft, fairly high-pitched voice anyway, and in some way he seemed almost the opposite of the ferocious rider he’d once been. When I asked him about Roubaix he gave me the usual ‘Stay near the front and don’t forget to eat’ advice. It was exactly the same advice that cyclists have been giving one another for 100 years, because staying near the front is quite important if you want to win a bike race. The difference was that the advice came from Johan Museeuw, so it was – and is – worth its weight in gold.

I had one of my rainbow jerseys with me that day. I’d ridden De Panne a few days earlier, and there’d been a time trial. I got the jersey out, signed it and gave it to Stefano. Then Johan opened up his bag and pulled out a jersey of the same design as the one he’d worn to win the 1993 Tour of Flanders, the Belgian tricolour. He said he wanted to give it to me, which as you can imagine was pretty humbling. He also pulled out one of his famous bandanas and signed it, ‘To Wiggo, Cheers. The Lion of Flanders.’ Then for some reason he gave me a load of cans of beer, as you do. They’re a little bit mad, the Flemish.

It had only taken me 22 years, but I’d got there in the end. I’d finally had the courage to meet Johan, and he’s a mate now. However, the fact that he’s a mortal, and vulnerable like the rest of us, doesn’t in any way diminish the bike rider he once was. It’s true that he wasn’t much for talking back then, but he’d bike races to win and he was under a colossal amount of pressure. He was the torchbearer for Flemish cycling, and that’s one hell of a weight to have to bear.

I keep telling him I’ll go over and ride the cobblestones with him some time. I’ll probably get round to it eventually, but then again maybe not. Time rolls on, but I’m still not sure I’m worthy. I may have won the Tour de France, but he’s still Johan Museeuw.

Still the Lion of Flanders.

Museeuw winning the World Championships, 1996.

(#ulink_cea6be11-5266-59f6-87ba-bc4785e154f7)

Riding through the mud in his last victory at Paris–Roubaix, in 2001.

I was speaking to my mum after having watched Museeuw win Flanders, and she explained that Eurosport would be showing something called ‘Paris–Roubaix’ the following Sunday. She said, ‘You know the mews out the back here, with the cobblestones? Well, they ride over roads like that, and the cobbled sections are called pavé.’ I couldn’t for one minute imagine how they’d be able to race their bikes over stuff like that, but I couldn’t wait.

And so it was that, on 11 April 1993, I was acquainted with the wonder that is Paris–Roubaix. My first impression was just how crazy the whole thing looked. And how spectacular. I’d only ever seen sporting events that took place in hermetically sealed stadiums, but this was something else entirely. Where Boardman had gone round and round the velodrome, here they were just flaying themselves for hour after hour. You had potholes, mud and dust everywhere, and those cobbles. Then you had guys just keeling over and falling off, people running with their bikes or carrying them, noise and bodies everywhere. I can only really describe the scene as organised anarchy, and I loved it. It may sound dramatic, but it’s no exaggeration to state that it was a life-changing moment for me.

It was an epiphany.

Two riders had broken away. One was a Frenchman named Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle, who’d won the previous year after having tried 15 times. The other was an Italian named Franco Ballerini, and he was doing all the work. He was trying to shake Duclos off, and every time he surged the electricity went straight through me. Somehow Duclos kept clinging on, and ultimately they came into the velodrome together. Then they did the sprint and literally crossed the line simultaneously.

To the naked eye it looked too close to call, but Ballerini was convinced he’d won. The race officials were looking at the photo finish, but he started riding his lap of honour anyway …

The closest Paris–Roubaix finish ever. Ballerini (left) being pipped to the line by Duclos-Lassalle in the Roubaix velodrome, 1993.

I UNDERSTAND WHAT PARIS–ROUBAIX means to people now, and I genuinely think he didn’t dare contemplate that he hadn’t won. I think he was actually trying to convince himself that he hadn’t lost. Paris–Roubaix was who Franco Ballerini was, and winning it was all he lived for.

In the end they gave it to Duclos, the French guy. He’d been on Ballerini’s tail for an hour, and then stolen round him and won by a few centimetres. Franco had been stronger (and nobody was in any doubt that he was the moral victor). Duclos, though, was one stealthy, resourceful bike rider, and he’d won by making damned sure he didn’t lose.

Ballerini had lost Paris–Roubaix, but in the process he’d won himself a new fan across the English Channel. I don’t suppose, in that precise instant, he would have cared one iota, though, because he was utterly inconsolable.

Franco Ballerini was a big, handsome guy with a unique way of riding across the cobbles. He had this straight-armed, slightly rocking, metronomic style that was completely different to the others. He also wore those wonderful, fluorescent Briko glasses, and I’d often find my teenage self trying to imitate him. Physically he was the Italian cycling archetype, but as a racer he was made-to-measure for the northern classics. In 1994 he was second at Gent–Wevelgem, third at Paris–Roubaix and fourth at Flanders. He was always among the strongest, but he tended to lose because he wasn’t particularly fast. In order to win he needed to drop everyone else, and of course that’s the hardest thing to do in cycling. His greatness lay in the fact that through all the disappointments he never buckled, and he never lost his conviction that one day he’d win Roubaix.

By 1995 he was riding for Mapei. They had Tony Rominger, Museeuw, Abraham Olano, Fernando Escartín and a young Frank Vandenbroucke, and were developing into the best team in the world, a team that would dominate cycling for almost a decade. Talking of which, it kind of makes me smile when cycling journalists refer to Sky as the ‘ruination of cycling’. In actual fact, there have always been wealthy, immensely powerful teams, and history tells us that they’ve generally been extremely good for the sport. The Bianchi, Peugeot, Molteni, Raleigh and Renault jerseys are iconic not because they’re particularly beautiful (though to my mind some of them are), but because they are synonymous with a moment in time. Sky are just the latest iteration of the superteam.

1996 Mapei jersey

I digress. Ballerini won Het Nieuwsblad (Het Volk, as was) in the freezing rain, and had really good form. However, three days before Roubaix he crashed at Gent–Wevelgem and dislocated his shoulder. He put the shoulder back in himself, but Ballerini’s Law seemed to have struck yet again. He hung around the hotel with his arm in a sling, praying that he’d recover in time, but when he went to bed on Saturday night it was 50–50. He agreed to give it a go the following morning, but he was kidding himself. He hadn’t been able to use a knife and fork for four days, let alone train for a 266-kilometre bike race over the cobblestones of northern France. The odds were stacked against him, to say the least.

But he was fresh, if nothing else, and it turned out that this was his day of grace. First one of his team-mates, a beast of a rider named Gianluca Bortolami, towed him across to the lead group. Then on Templeuve, a cobbled section 30-odd kilometres from Roubaix, Ballerini simply put on another gear and just rode away. From the best classics riders in the world.

It’s often the commentary that characterises the most iconic sporting moments. Just as Sergio Agüero’s title-winning goal for Manchester City has become indivisible from Martin Tyler’s commentary, my abiding memory of that race is David Duffield’s singalong voiceover. As Ballerini rode around the velodrome alone, old Duffers put on his very best Italian accent. It went something like, ‘Fran-co-Ba-lle-rini-born-in-Fi-ren-ze …’ Duffers’s accent was rubbish, but that didn’t matter at all because the moment was magical – and if I’m honest, it still is. Through all the stresses and strains of my own cycling career and post-career, that episode still brings a smile to my face. It’s the unadulterated pleasure of cycling, pure and simple.

Ballerini celebrating after winning his second Paris–Roubaix.

Ballerini won Roubaix again in 1998, and it’s no coincidence that he chose to retire there in 2001. By then he was 36, and he rolled into the velodrome alone in 32nd place. He was caked in Paris–Roubaix mud, and that was entirely appropriate given that the race had defined his cycling career – and vice versa – for the preceding 15 years. You’ll often see bike riders zip up their jersey as they approach the finish line, the better to expose their sponsor’s name to the TV cameras. Ballerini, though, did the opposite. He unzipped his jersey, because he wanted the world to see his undervest. On it, in large blue letters, were printed two words:

MERCI ROUBAIX.

Just perfect.

With unzipped jersey in the Roubaix velodrome at his last major professional race, in which he finished 32nd.

By the time I turned professional I’d seen Ballerini’s exploits ad infinitum, so when I was selected for the 2003 Paris–Roubaix it was a dream. I was 22, I’d got round Flanders the previous week, and I was about to join the Paris–Roubaix pantheon. I was with FDJ, and our protected riders were Jacky Durand, Christophe Mengin and Frédéric Guesdon, a previous winner. Our DS was Marc Madiot, whom I’d watched win it on TV, and before the race he gave us this big, dramatic, stirring team talk. He explained what it signified, the legend behind it, all the stuff I’d been daydreaming about since I watched Duclos and Ballerini slugging it out ten years earlier. To say I was excited would be an understatement.

So I knew all about it, knew every sector of the pavé, knew all the theories about riding it because I’d seen it on TV so many times. Nobody else really knew the first sectors because they were never televised, but I’d spent the preceding days reeling the names off to anyone who would listen. And indeed to anyone who wouldn’t. I was a proper nerd.

Although Ballerini had retired, a lot of my boyhood heroes were still racing. Museeuw was there, Peter Van Petegem was there, Erik Zabel and Fabio Baldato were there … About 10 kilometres from the first sector I was near the front and, I have to say, doing a decent job. I was staying out of the way of the champions while simultaneously keeping Durand out of trouble. I’d have been about 20th, then suddenly there was a massive crash just behind me. It wiped everyone out, so now you’d a select group of 20. Essentially it was comprised of everyone who was anyone – and me, Bradley Wiggins, who wasn’t.

I wasn’t trying to mix it up at the front because I had no place there, but by the time we reached the entrance to the Arenberg I was feeling really pleased with myself. That’s because the Arenberg is … well, the Arenberg, and I was in the lead group with the best of them. Then, wouldn’t you just know it, 100 metres into the forest the guy in front of me, Kevin Van Impe, got his front wheel stuck in the gutter. He hopped it out, but his back wheel stayed in. He slid off in front of me, and I had no chance whatsoever. I just clattered straight into him and flew straight over the top of the bars.

I’d gone into ‘The Trench’ with the champions, and come out of it with a little group of back-markers. I had a buckled back wheel, and my knee and elbow hurt like hell. I couldn’t hold the bars, let alone ride over the cobbles, so I had no choice but to climb into the broomwagon. Paris–Roubaix had broken me in two, but I was immediately transported back to A Sunday in Hell, a documentary film about the 1976 race that I’d watched fanatically as a kid. There was a shot of two riders in the wagon, and they were telling the driver what had happened to them. Now here I was doing exactly the same thing. It sounds perverse – well, it actually is perverse – but I took some pleasure in that because in some way I was standing on the shoulders of giants. Giants in the sagwagon, but giants all the same.

The Arenberg, Paris–Roubaix 2014.

I went back the following year, and again in 2005. I packed in both times, and by then the ‘romance’ of Paris–Roubaix was starting to wear thin. As a spectacle it was great, and I never failed to appreciate the grandeur of it. The problem was that actually riding it was ridiculous, a shit-fight I had not a prayer of winning. However hard I tried, something always went wrong. I couldn’t figure it out. I seemed to be one of the hopeless, anonymous dozens that get sent there to make up the numbers.

And yet, I was desperate to be a factor there, and deep down I still believed I could be. I could ride, I knew how to read a race, and my bike-handling skills were good. I’d been World Madison champion, and logic suggested that if I were ever going to be competitive in a classic, it would be Roubaix. The problem was that Roubaix always did have its own twisted, indecipherable logic, and it kept making a mug of me.

In the summer of 2005 I finally got to meet Franco Ballerini, at the World Championships in Madrid. By then he was manager of the Italian national team, and he walked into the GB tent an hour and a half before the time trial. I thought, ‘Bloody hell! That’s Franco Ballerini!’, and then Max Sciandri introduced us. Max started talking to him in Italian, telling him who I was and what I’d done. I felt ten feet tall.

I signed for Cofidis in 2006, having finally resolved to make a go of my road career. I decided to give Paris–Roubaix another shot, and found myself in a good position headed into the Arenberg. I wasn’t strong enough to stay with the likes of Cancellara, Boonen and Ballan, but I settled into the main chase group of about 50 or so. Looking round I noticed that many of them were classics specialists, real class acts. I was relatively comfortable among them, and I remember being interviewed in the velodrome afterwards. I said, ‘Well, even if I never do it again I’ll always be able to say I finished Paris–Roubaix.’ Three years later I went back, finished 25th and realised I had the ability to be competitive. I was a million miles away from winning the thing, but at least I was relevant.

Franco Ballerini died tragically in 2010, co-piloting in a rally in Tuscany. It had a profound impact on me, but also on the Italian riders who’d ridden under him. I’d idolised him as a bike rider but guys like Pippo Pozzato loved him, almost without exception, as a human being.

All of which largely explains my own efforts at the 2014 and 2015 Paris–Roubaix. In 2014 I was focused on trying to earn selection for the Tour team, so I wasn’t specifically prepared for Roubaix. I was in decent form, but I was mainly concentrating on being good for the Tour of California. Notwithstanding all of which, I was at the front all day, and I had the strength to attack in the finale. They caught me, and Niki Terpstra went clear, but I came in with Boonen, Štybar and Cancellara. I finished top ten in a race I’d never really targeted, because in my best years my career path had taken me elsewhere. Roubaix requires colossal strength and stamina, but as I’d acquired them I’d been focused, necessarily, on the Tour.

Regardless, I’d proved that I could be a player at the Hell of the North, and in 2015 I wanted to have a serious shot at it. I knew I’d need the cards to fall my way (you always need that at Roubaix, unless you’re a Boonen or a Cancellara), but I was one of the elder statesmen of the peloton. The flip-side was that I was in a team containing guys like Flecha, Thomas, Stannard and Hayman, experienced riders who were more than capable of challenging for the win themselves.

The DS was Knaven, and he’d won Roubaix in 2001. When I put my hand up I knew I’d have the support of all of these people, but it was implicit that I’d need to perform. If you’re asking guys like Stannard to sacrifice themselves for you, you’d better have the legs to justify it.

The rest is history. I attacked on the Templeuve, and that was no coincidence. Rather it was my way of paying tribute not only to the race itself, but also to Franco Ballerini. It was my way of honouring his memory, while simultaneously realising, as best I could, my own boyhood dream. In retrospect it probably wasn’t the smartest thing to have done, but cycling’s not all about watts, power meters and tactics. To me this was the very opposite of those things, and I like to think that Ballerini was of the same mind.

I didn’t win Roubaix – I wasn’t half the classics rider he was – but hopefully he’d have approved.

Franco Ballerini’s 1994 Mapei-Clas Colnago Titanio Bittan

(#ulink_6567ab6c-e8ec-5e7e-a526-6fbf4e170e51)

Racing in 1992 for the Banana-Met team.

So I’d ‘met’ Museeuw and Ballerini, and shaken hands with Flanders and Paris–Roubaix. Next up would be a visit to the Milk Race, a pro-am Tour of Britain. I couldn’t wait to see real-life riders in the flesh, but in the meantime I had my 13th birthday. Like anyone starting out in cycling, I’d quickly become obsessed by its equipment and I wanted the same gear as the champions had. I wanted to ride like them and look like them, and that meant one thing and one thing only. A date with destiny for me, and a long haul down to the cycling heartlands of deepest, darkest Croydon for my poor, put-upon mother.