По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

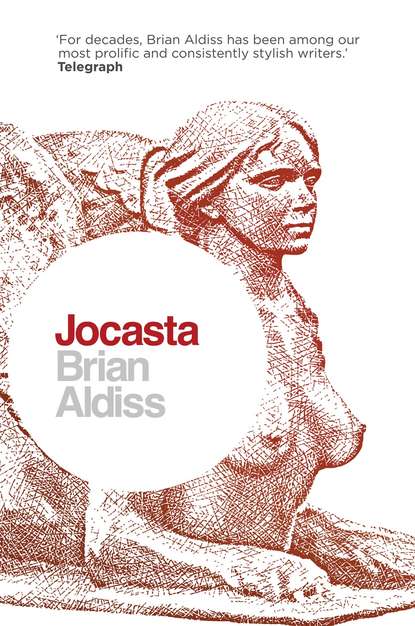

Jocasta: Wife and Mother

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A serpent appeared in the air before him. This was no emblem of Apollo. It was winged, writhing to make its golden scales gleam. A light, at first soft, then blinding, filled the chamber. Still crouching, for he scarcely dared move, Oedipus cast his gaze upwards, under his eyebrows.

In place of the snake a female of radiant beauty materialised. Her jet black hair was ringleted and fell to her snowy shoulders. Her gown, gathered at the waist with a chain of flowers, was so flimsy it scarcely concealed the greater beauties beneath its folds. Her thighs were snowy white. On her wrists she wore serpentine bracelets, and about her ankles similar enhancements in pure gold.

‘Oh, radiant creature, are you not the wood nymph Thalia?’ asked Oedipus, surprised. He attempted to rise. She gestured with her right hand, so that he remained fixed in his crouched position.

When she spoke, her voice was so soft that it came to him borne on unimagined perfumes. ‘I am as you say, O Oedipus, the wood nymph Thalia. I am come from Apollo, whom I serve as messenger, to speak with you.’

‘Will not Apollo speak with me?’ He could scarcely hear his own voice for the nymph’s radiations, which seemed half-scent, half-music.

‘Hera, the goddess of moonlight and fertility, sent the Sphinx to punish King Laius for his sins. Instead Laius was killed by mortal man.’ As she spoke, Thalia regarded Oedipus intensely with her dark eyes. He found himself unable to move under the power of that gaze. Her eyes had appeared beautiful. Now they were frightening and filled with the emptiness of night.

Although her carmine lips moved when she spoke, their sounds seemed to come from elsewhere.

‘What of this matter? How does it concern me?’ Oedipus asked, with such pride as he could command from his inferior position. ‘Laius is nothing to me.’

‘You have won the Sphinx, O Oedipus,’ said the mysterious nymph, ‘but when the Sphinx dies, you will die also. The Sphinx is a remaining daughter of an older age, an age before you men began to become entirely human. Recall how her body parts represent the seasons – the woman’s head standing for Hera, the goddess, while the lion’s body, the eagle’s wings and the serpent’s tail stand for the three ancient agricultural seasons, spring, summer, winter.

‘Soon, I foresee, the Sphinx will die. Soon the gods also must die. They cannot live in the dull, materialistic world to come, when magic has died like the light of an oil lamp.

‘Do you not recall from your childhood the eight-year solar-lunar calendar, O Oedipus? That calendar which the Sphinx embodies?’

‘I lived in Corinth and studied new sciences. I recall nothing of which you speak.’ Yet, pronouncing the words from his confining crouch, he suddenly, in a trick of the mind, did recall the words of Jocasta’s old grandmother Semele. The hag was well familiar with the ancient succession of the seasons.

In her younger age, Semele had worn a dress with eleven pendants. She explained the pendants as signifying the discrepancy of eleven days between solar and lunar years. She had talked to them over and over of the sacred union of sun and moon. It was necessary to believe in it, she said. All magic sprang from that union, that discrepancy.

Oedipus and Jocasta had listened, unwilling to believe a word Semele said: yet, in their confusion, partly believing. The wild lady, sitting there in the candlelight, talking, talking, carried undeniable conviction.

She had talked over and over as they sat at table at night, with the candles guttering and the platters pushed aside; Semele amusing them with tales of her early youth, when she was indoctrinated into magic, the wine liberating her tongue.

On those occasions, he had seen her beauty, so different from Jocasta’s.

‘I do recall,’ he told Thalia, with a sense of misery that those times, for which he had then had no particular affection, were now over and gone for ever.

‘You do well to recall …’ said the nymph in her musical voice. ‘The calendar may change. The seasons do not change. Some things are immutable …’ She bestowed on him a sweet smile that yet he found threatening.

He roused himself, asking why she had said that the Sphinx would die.

She gave him another smile, rather less friendly than the previous one. ‘She will die through your fault, your carelessness, O Oedipus!’

Thalia’s luminance seemed to grow more intense. Was he conscious or did he dream? He had quaffed a beaker of the sweet wine they sold at the temple door. What had it contained beside the fruit of the grape?

‘Yes, the solar-lunar calendar … The sun and moon begin and end the cycle in step. That’s when new moon and winter solstice coincide.’ He spoke as if to talk at all was to sleepwalk. ‘But the lunar year of twelve moons is shorter than a solar year by eleven days. So the sun takes – as they used to say – three steps and halts at the end of the third and sixth year. Then a thirteenth month brings sun and moon almost in step again.

‘So the sun … mmm … oh, yes, so the sun goes sometimes on three feet. Then after two more solar years, a further month of thirty days is needful – that’s to say, at the end of the eighth year, ending the cycle. So it sometimes goes on only two feet.’

‘That’s not quite all,’ said Thalia, encouragingly.

He remembered. The young Semele had drawn a figure on the table with a finger dipped in her wine. ‘You used also to add a single day every four years, or leap years. So that occurred twice in the eight-year cycle. You could say that the sun sometimes went on four feet, but is at its weakest then, in the sense that it is only one day ahead of the moon.

‘That was how it was, I believe.’

A silence prevailed. The flambeau crackled, its light dulled by the radiance of the wood nymph, who seemed to be waiting for Oedipus to speak again. Her skin, of an intense pallor, appeared to be a source of light.

He did speak again. The words seemed forced from him. ‘Helios is the sun god. He speaks with one voice. His queen is the moon goddess … So that was once the answer to the Sphinx’s riddle. Are you telling me that?’

‘You are telling me that.’ He saw that he was adrift with her, passing high over a green mountainside. The moon stood still in the heavens. Her delicate fingertips touched his. It was a moment of extreme unction. The snake was guiding him. He was not afraid. He was free of earthly problems.

‘You are telling me that.’ Thalia was looking about her rather anxiously, as if in fear of vultures. ‘You have now answered the riddle a second time, in two voices.’

They seemed to be encompassed in a glowing cloud, and without weight. Distantly to his ears came his own question.

‘But why did the Sphinx accept my first answer?’

‘Perhaps she was tired of killing other fools …’ Her voice seemed faint and distant. ‘Or it was a question of time …’

Fearing she would disappear completely, Oedipus cried, ‘Stay, sweet nymph! Will not Apollo spare me now?’

She looked at him, full in the face. Her countenance, he now saw, was but a mask; behind it waited a snake, ready to strike.

He was confused and alarmed, not least because the mask seemed to resemble the face of Jocasta. He floundered, seeking to disregard the illusion.

‘Spare me!’

The response came without comfort for his confusion.

‘Life is a labyrinth. You must solve the riddle of your own personality – if you can … if you can …’ Her laughter was faint, was a cackle, was a crackle, was the noise and splutter of the flambeau dying into its socket, the ribs of the sacrificed lamb scorching in its ashes. Oedipus found that he lay sprawled on the cold tiles of the temple. He rose up groaning. The mountainside was gone, the serpent, the nymph. The flame died. He found himself alone in the stifling dark.

His forehead burned.

‘Apollo!’ he cried in anger and supplication.

No answer came.

Jocasta could not sleep. The ever-restless sea brought a breeze into her tent which disturbed her. And perhaps there was something more; she could not tell. She lay wakeful, her right hand tucked between her legs. She resented the power of the gods, and resented the way human beings submitted themselves to their whims.

Anxiety grew. She stepped over the snoring Hezikiee without waking her, to urinate outside the tent.

Confronting the night, she walked barefoot on the beach, drawing into her mind soothing things: the murmur of the waves on the shore, and the moon undergoing its small changes. Could the moon, she questioned, be a goddess? She wondered what the stars were. Could they be the souls of the dead, as her mother had told her?

Jocasta was often troubled by her own introspection. She hid it guiltily from others. Even now, on the mild murmuring shore, old worries returned. Although she was aware of her physical being, of her feet scratched by the sand beneath them, there was a moment when she also saw herself as possessing a detached self, a self which looked on coolly at her actions, possibly with contempt.

She was aware of a change in the level of her consciousness, as if distant music had ceased in mid-chord. She stopped and looked about her. A man materialised from behind a bush of rosemary, rising slowly from a crouched position. She was startled, but would not show it.

The man was old, offering her no threat. He told her not to be alarmed, raising a hand in greeting to show it was empty of weapons. His beard was white, his shoulders bowed. He walked with a staff. Coming to stand before her, he sank the end of the staff into the sand for greater stability. Once she could study his face by the pallid light from above, she had no more fear, for his aspect was one of shrewd benevolence.

‘You should be in bed at your age,’ she said.

‘The old and the guilty find little comfort in bed,’ he replied.