По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

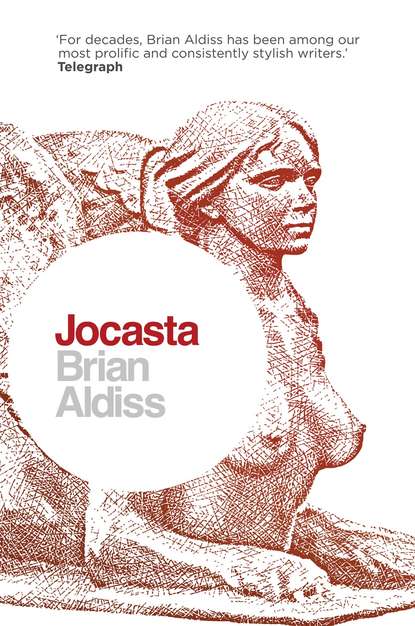

Jocasta: Wife and Mother

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In silence they regarded each other. A dog was barking distantly inland.

His remark quelled her: she felt that this stranger had recognised her inner confusions. Relief and anxiety struggled within her, making her dumb. Perhaps he mistook her silence for foolishness.

‘Lady, how intelligent are you?’ he asked.

She disliked the impropriety of the question. ‘I am a queen, if a wakeful one. Is that not enough?’

‘Probably not, although you may think it so. My intention was not to challenge you, although I perceive you are troubled in mind. I was considering – when you interrupted my musings – by what means I might measure how distant the moon is from us.’

‘Is the moon solid?’

‘I believe it to be as solid as is the world we tread.’

‘Is it made of silver, then?’

‘No more than is the sand beneath our feet.’

‘Why should you wish to know how distant it is?’

He shook his head slowly. ‘If knowledge is there to be had, we should endeavour to obtain it, as we endeavour to eat the food set before us. The chances are that knowledge might make us better people. Or more sensible, at least. Is the moon, for instance, nearer to us than the sun, as I suspect? Why does it not burn us, as does the sun?’

Jocasta breathed a sigh. ‘It is not intelligent to ask such questions. They are remote from our lives.’

‘Ah, lady, but not from our imaginative lives!’

Jocasta thought about that. ‘Then I will put to you a different sort of question, a question for which I seek an answer, which affects all human beings.’

‘What question may that be?’ he asked as if humouring her, without any show of curiosity.

‘We live imprisoned in the present time as we move along the path of our lives. Yet we know that the past existed; it remains with us like a burden. So that past must be still in existence, although we cannot see it. Like a path we traversed on the other side of a hill, perhaps. I ask you if the future exists similarly – also unseen – and if there is one path only we can tread there. Or can we choose from many paths?’

The old man leant on his staff and was silent. Then he spoke.

‘These times of which you speak are not like the moon, which has physical existence. It is mistaken to think of times as physical pathways. These times of which you speak are qualities, not quantities. You understand that? Perhaps you do understand, or you would not have asked the question.’

She said gently, ‘But you have not answered my question. Is the future a single path or many?’

The old man shook his head. ‘What will guide you through the future is your own character. Your character is your compass. It is a quality like time. They must be matched, I believe.’

Jocasta thought of her own perceptions of the world, and found them limited. She longed to converse more intimately with this gentle old man.

She rubbed the tip of her nose. ‘I don’t understand you. Your answers unfortunately are as incomprehensible as your questions.’

‘You think so? Someone must ask the questions. Someone must answer the questions. Of course, those answers may not be clear. Why should the moon be fixed, let’s say, a quarter of a million miles from us? Why should you, a fairly young woman, bother about what is to come, any more than what is past?’

His responses baffled Jocasta. ‘We all bother about what is to come, don’t we?’

The old man spoke again. ‘My name, madame queen, is Aristarchus, Aristarchus of Samos, a mathematician of Alexandria.’ He did not suppress a note of pride as he introduced himself, bowing over his staff. ‘I have in my life answered one great puzzling question. I have worked out – and my solution has been confirmed by certain Athenians – that it is not the sun that goes round the earth, but the earth that goes round the sun.’

She gave a grunt of contemptuous laughter. ‘Divination! Often unreliable.’

‘Mathematics. Always reliable.’

‘Then you are surely mistaken. We can see that the earth is stationary and that the sun goes round it. Any fool can tell that, ancient Aristarchus.’

Unperturbed, he replied, ‘Fools can tell us many wrong things. Fools mock me for my deduction, yet I have arrived scientifically at my conclusion. The earth is round, and travels about the sun in a grand circle. The earth also rotates on its axis, like a wheel, making day and night. At a lunar eclipse, we see from the earth’s shadow on the moon that it is a round body.

‘You must think more rationally. The old life of magic is dead, or all but dead. We are now in a new epoch, which offers much more than the old.

‘The past has no existence, except in our memories, nor the future either, except in our expectations. Your future may lie within you, curled up, sleeping within your nature. You must not become a slave to appearances.’

‘I prefer appearances …’ She turned away. ‘I regret I am not able to talk more. Your speech only confuses me. Goodnight, Aristarchus of Samos.’ She walked away down the beach.

He called in his weak voice, ‘Do not fear confusion. Doubt is a better guide than faith.’ The words were almost lost beneath the sound of the lapping of the waves, yet she heeded them.

She stopped and turned back. ‘I apologise if I have been impolite. I am glad to have spoken to a wise and distinguished man. I regret that my mind is burdened. I make bad company. I’m sorry …’

He raised a hand in benediction and farewell. She found there were tears in her eyes.

The old man’s words were too unsettling. Surely she could not be as mistaken in her perceptions as his statements implied …

He had said that both past and future were qualities. What else had he said? Had he said there was no future path? Had he said, ‘You must not judge by appearances …’?

Perhaps there was sense in that remark, as in much he had said. Jocasta was disturbed to think that her response, about preferring appearances, which she had considered clever at the moment, was rather silly …

Appearances differed so sharply from realities.

In the early hours of the morning, when the moon sank beyond the shoulder of the hill, she dreamed she was blind and alone in the world.

After his vigil, Oedipus slept. His slumbers were drugged, for once again Apollo had turned his face against him.

Ismene wakened her mother, who was sleeping heavily. ‘Mother, the sun has come up, and so must we be.’

Jocasta said heavily, ‘It’s not that the sun has come up. Rather the other way round.’

Ismene laughed. ‘Wake up, Mother!’

Jocasta lay where she was, fatigued by sleeplessness, trying to go over in her mind the conversation with Aristarchus. Had it happened or had it been a vivid dream?

In a while, Antigone came to her mother, kneeling by her and looking earnestly into her face.

‘How are things with you, Mother? Did you sleep badly?’

Jocasta put an arm about Antigone’s neck and kissed her cheek.

‘No, I slept well and had a beautiful dream.’

Later, Antigone and Ismene walked with their brothers among the market stalls, followed by their personal servants. The stalls were pitched along the land that ran on the cliff above the beach and led to Apollo’s temple. There were decorative objects of bronze to be bought, mirrors and suchlike, and pendants of blue glass, wooden toys from eastern lands, perfumes, drugs, bangles, sandals for women’s feet, bright-dyed costumes, rugs from the southern climes, figs and foods of all sorts.