По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

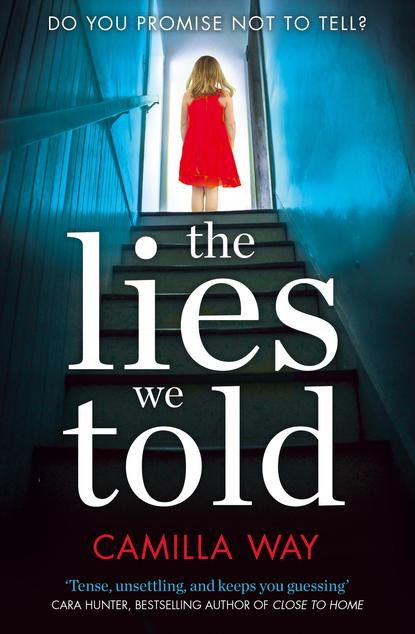

The Lies We Told: The exciting new psychological thriller from the bestselling author of Watching Edie

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But his text half an hour later said, No one’s heard from him. I’ll keep trying though, I’m sure he’ll turn up.

She couldn’t shake the feeling something was very wrong. Despite his colleagues’ laughter, she didn’t really think he’d been with another woman. Even if he had, a one-night stand didn’t take this long, surely? She made herself face the real reason for her anxiety: Luke’s ‘stalker’.

Putting the word in inverted commas, treating it all as a bit of a joke, was something Luke had done ever since it had begun nearly a year ago. He’d even christened whomever it was ‘Barry’ – a comical, harmless name to prove just how unthreatened he was by it all. ‘Barry strikes again!’ he’d say, after yet another vicious Facebook message, or silent phone call, or unwelcome ‘gift’ through the post.

But then things had got weirder. First an envelope stuffed with photographs had been pushed through their door. Each one was of Luke and showed him doing the most mundane of things – queuing at a café, or walking to the Tube, or getting into their car. Whoever had taken them had clearly been following him closely – with a wide-angled lens, Mac had said. It had made Clara’s skin crawl. The photos had been stuffed through their letterbox with arrogant nonchalance, as if to say, This is what I can do: look how easy it is. But though she’d been desperate to call the police, Luke wouldn’t hear of it. It was as if he was determined to pretend it wasn’t happening, that it was merely an annoyance that would soon go away. And no matter how much she begged, he wouldn’t budge.

And then, three months ago, they’d come home late from a party to find the door to their flat forced open. Clara would never forget the creepy chill she’d felt as they silently walked around their home, knowing some stranger had recently been there – going through their things, touching their belongings. But the strange thing was, everything had been left in perfect order: nothing had been stolen; nothing, as far as she could tell, had been moved. Only a handwritten message on a page torn from Clara’s notepad was sitting on the kitchen table: I’ll be seeing you, Luke.

At least Luke had been sufficiently rattled to let Clara report that to the police. Who didn’t even turn up until the next day and discovered precisely nothing – the neighbours hadn’t seen anything, no fingerprints had been found – and as nothing had been taken or damaged, within days the so-called ‘investigation’ had quietly fizzled out.

Stranger still, after that, it was as if whoever it was had lost interest. For weeks now there’d been no new incidents, and Luke had been triumphant. ‘See?’ he’d said. ‘Told you they’d get bored eventually!’ But although Clara had tried hard to put it out of her mind, she hadn’t quite been able to forget the menace of that note – or the idea that the culprit was still out there somewhere, biding their time.

And now Luke had disappeared. What if ‘Barry’ had something to do with it? Even as she allowed the thought to form she could hear Luke’s laugh, see his eyes roll. ‘Jesus, Clara, will you stop being so dramatic?’ But as the morning progressed her sense of foreboding grew and when lunchtime came, instead of going to her usual café, she found herself walking back towards the Tube.

She reached Hoxton Square half an hour later, and when she caught sight of her squat, yellow-bricked building on its furthest corner, she was struck suddenly by the overwhelming certainty that Luke would be there waiting for her, and she ran the final few hundred yards, past the restaurants and bars, the black railings and shadowy lawn of the central garden and, out of breath by the time she reached the front door, she impatiently unlocked it before sprinting up the communal stairs to her flat. But when she got there, it was empty.

She sank into a chair, the flat too silent and still around her. On the coffee table in front of her was a photo she’d had framed when they’d first moved in together and she picked it up now. It was of the two of them on Hampstead Heath three summers before, heads squashed together as they grinned into the camera, a scorching day in June. That first summer, the days seemed to roll out before them hot and limitless, London theirs for the taking. She had fallen in love almost instantly, as effortlessly as breathing, certain she had never met anyone like him before, this handsome, exuberant man so full of energy and sweetness and easy charm and who, (inexplicably it seemed to her) appeared to find her just as irresistible. As she gazed down at the photo now, their happiness trapped and unreachable behind glass, she traced his face with her finger. ‘Where are you,’ she whispered, ‘where the bloody hell are you, Luke?’

At that moment she heard the front door slam two floors below and her heart lurched. She listened, her breath held as the footsteps on the stairs grew louder. When they paused outside her door she sprang to her feet and rushed to open it, but with a jolt of surprise found it was her upstairs neighbour, and not Luke, staring back at her.

She didn’t know the name of the woman who’d lived above them for the past six months. She could, Clara thought, be anything between mid-twenties and mid-thirties, it was impossible to tell. She was very thin with long, lank brown hair, behind which could occasionally be glimpsed a small, finely featured face covered in a thick, mask-like layer of make-up. In all the time Clara and Luke had lived there she’d never once replied to their greetings, merely shuffling past with downcast eyes whenever they met on the stairs. Every time either of them had gone up to ask her to turn her music down, which she played loudly night and day, she refused to answer the door, merely turning the volume up higher until they went away.

‘Can I help y—’ Clara began, but the woman had already begun heading towards the stairs. Clara was watching her go when her worry and stress got the better of her. ‘Excuse me!’ she blurted, and her neighbour froze, one foot poised on the first step, eyes averted. ‘It’s about the music. Could you give it a rest, do you think? It’s all night long, and sometimes most of the day too, can’t you turn it down once in a while?’

At first it seemed the woman wasn’t going to reply, but slowly she turned her face towards Clara. Her eyes, rimmed thickly in black kohl, landed on her own before flitting away again, as she asked softly and with the faintest ghost of a smile, ‘Where’s Luke, Clara?’

Clara could only stare back at her, too surprised to respond. ‘I’m sorry?’

‘Where’s Luke?’

She’d had no idea the woman even knew their names. Perhaps she’d seen them written on their post, but it was the way she said it – so familiar, so knowing, and with such a strange smile on her lips. ‘What do you mean?’ Clara asked but the woman only turned and carried on up the stairs. ‘Excuse me! Why are you asking about Luke?’ but there was still no reply. Clara stood staring after her. It was as if the world was conspiring in some surreal joke against her. The door to the upstairs flat opened and then closed again and at last Clara went back to her own flat. She stood in her narrow hallway, listening, until a few seconds later the familiar thud of bass began to thump against her ceiling once more.

It was past two. She should go back to work; her colleagues would be worried by now. But Clara didn’t move. Should she start phoning around hospitals? Perhaps she should google their numbers – at least that way she would be doing something. She went to the small box room they used as an office and at a touch of the mouse pad Luke’s laptop flickered into life, the browser opening immediately at Google Mail – and Luke’s personal email account.

For a second she stared at the screen, her finger hovering, knowing she shouldn’t pry. But then her gaze fell upon his list of folders. Below the usual ‘Inbox’ ‘Drafts’ and ‘Trash’ was one labelled, simply, ‘Bitch’. She stared at it in shock before clicking on it. And then her jaw dropped – there were at least five hundred messages, sent from several different accounts over the past year, sometimes as often as five times a day. She opened and read them one by one.

Did you see me today, Luke? I saw you. Keep your eyes peeled.

And,

I know you, Luke, I know what you are, what you’ve done. You might have most people fooled, but you don’t fool me. Men like you never fool me.

How are your parents, Luke? How are Oliver and Rose? Do they know the truth about you – your family, your friends, your colleagues? How about that little girlfriend of yours, or is she too stupid to see? She looks really fucking stupid, but she’ll find out soon enough.

And,

Women are nothing to you, are we, Luke? We’re just here for your convenience, to fuck, to step over, to use or to bully. We’re disposable. You think you’re untouchable, you think you’ve got away with it. Think again, Luke.

Then,

What will they say about you at your funeral, Luke? Say your goodbyes, it’s going to be soon.

The very last one had been sent only a few days before.

I’m coming for you, Luke, I’ll be seeing you.

It had been a woman, all this time? And he’d known about it for months, had known but hadn’t told her – had never even mentioned the emails. Did he know who it was? It was clearly someone who knew him very well – knew his parents’ names, where Luke worked; knew his movements intimately. Was it the same person who had broken into their flat, sent the photographs, the letters? Perhaps it was a joke, she thought wildly. An elaborate prank dreamt up by one of his friends. But then, where was he? Where was Luke? I’m coming for you, Luke. I’ll be seeing you.

She was deep in thought when the sound of her intercom sliced through the silence, making her jump violently, her heart shooting to her mouth.

3 (#ue70a4556-8226-543c-897a-85987657e7d8)

Cambridgeshire, 1986

We waited such a long time for a baby. Years and years, actually. They couldn’t tell us why, the specialists. Couldn’t find a single reason why it didn’t happen for Doug and me. ‘Unexplained Infertility,’ was the best they could come up with. You think it’s going to be so simple, starting a family, and then when it’s taken from you, the future you’d imagined snatched away, it feels like a death. All I ever wanted was to be a mum. When school friends went off to university or found themselves jobs down in London, I knew it wasn’t for me. I didn’t want to be a career woman, didn’t need a big house and lots of money. I was content with our cottage in the village I’d grown up in, Doug’s building business; I just wanted children, and Doug felt exactly the same way.

I used to see them when they came back to our village for holidays, those old classmates of mine. And I’d see how they looked at me, with my clothes from the market and my lack of ambition, see the flash of superiority or bewilderment in their eyes when they realized I didn’t want to be just like them. But I didn’t care. I knew that what I wanted would bring me all the happiness I’d need.

Year by year, woman by woman, things began to change. They began to change. As we all neared our thirties, baby after baby began to make their appearance on those weekend visits. Of course, I’d been trying for a good few years by then, had already had many, many months of disappointment to swallow, but nothing hit me quite as hard as seeing that endless parade of children of the girls I used to go to school with.

Because I could see it, in their faces, how it changed them. How overnight the nice clothes and interesting careers and successful husbands which had once defined them became suddenly second place to what they now had. It wasn’t the change in them physically; the milk-stained clothes or the tired faces, it wasn’t the harassed air of responsibility or the being a member of a new club or even the obvious devotion they felt. It was something I saw in their eyes – a new awareness, I suppose – that most hurt me. It seemed to me as though they’d crossed into another dimension where life was fulfilling and meaningful on a level I could never understand. And the jealousy and despair I felt was devastating. Plenty of women, I knew, were happily childfree, leading perfectly satisfying lives without kids in them, but I wasn’t one of them. For as long as I could remember, having a family of my own was all I’d dreamt of.

So, when finally, finally, our miracle happened, it was the most amazing, most joyful thing imaginable. That moment when I held Hannah in my arms for the first time was one of pure elation. We loved her so much, Doug and I, right from the beginning. We had sacrificed so much, and waited such a long time for her, such a horribly long time.

I don’t remember exactly when the first niggling doubts began to stir. I couldn’t admit it to myself at first. I put it down to my tiredness; the shock and stress of new motherhood, or a hundred other different things rather than admit the truth. I didn’t let on to anyone how worried I was. How frightened. I told myself she was healthy and she was beautiful and she was ours, and that’s all that mattered.

And yet, I knew. Somehow I knew even then that there was something not quite right about my daughter. An instinct, of the purest truest kind, in the way animals sense trouble in their midst. Secretly I would compare her to other babies – at the clinic, or at Mother and Baby clubs, or at the supermarket. I would watch their expressions, their reactions, the ever-changing emotions in their little faces and then I’d look into Hannah’s beautiful big brown eyes and I’d see nothing there. Intelligence, yes – I never feared for her intellect – but rarely emotion. I never felt anything from her. Though I lavished love upon her it was as though it couldn’t reach her, slipping and sliding across the surface of her like water over oilskin.

At first, when I voiced my concerns to Doug, he’d cheerfully brush them aside. ‘She’s just chilled out, that’s all,’ he’d say, ‘let her be, love,’ and I’d allow myself to be reassured, telling myself he was right, that Hannah was fine and my fears were all in my head. But when she was almost three years old, something happened that even Doug couldn’t ignore.

I was preparing breakfast in the kitchen while she sat on the floor, playing with a makeshift drum kit of pots and pans and spoons I’d got out to entertain her with. She was hitting one pan repeatedly over and over, the sound ricocheting inside my skull, but just as I was mentally kicking myself for giving them to her the noise suddenly stopped. ‘Hannah want biscuit,’ she announced.

‘No, darling, not yet,’ I said, smiling at her. ‘I’m making porridge. Lovely porridge! Be ready in a tick!’

She got up, said louder, ‘Hannah want biscuit now!’

‘No, sweetheart,’ I said more firmly. ‘Breakfast first, just wait.’

I crouched down to rummage in a low drawer for a bowl, and didn’t hear her come up behind me. When I turned, I felt a sudden searing pain in my eye and reeled backwards in shock. It took a few moments to realize what had happened, to understand that she’d smashed the end of her metal spoon into my eye with a strength I never dreamed she had. And through my reeling horror I saw, just for a second, her reaction; the flash of satisfaction on her face before she turned away.

I had to take her with me to the hospital, Doug not being due back for several hours yet. I have no idea whether the nurse in A&E believed my story, or whether she saw through my flimsy excuses and assumed me perhaps to be a battered wife, one more victim of a drunken domestic row. If she did guess at my shame and fear, she never commented. And all the while Hannah watched her dress my wounds, listened to the lies I told about walking into a door with a silent lack of interest.

Later that evening when she was in bed, Doug and I stared at each other across the kitchen table. ‘She’s not even three yet,’ he said, his face ashen. ‘She’s only a little girl, she didn’t know what she was doing …’

‘She knew,’ I told him. ‘She knew exactly what she was doing. And afterwards she barely raised an eyebrow, just went back to hitting those damn pots like nothing had happened.’

And after that, Hannah only got worse. All children hurt other kids, it happens all the time. In every playgroup across the country you’ll find them hitting or biting or thumping each other. But they do it out of temper, or because the other child hurt them, or to get the toy they want. They don’t do it the way Hannah did – for the sheer, premeditated pleasure of it. I used to watch her like a hawk and I’d see her do it, see the expression in her eyes as she looked quickly around before inflicting a pinch or a slap. The reaction of pain was what motivated her. I knew it. I saw it.