По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

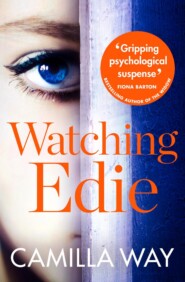

The Lies We Told: The exciting new psychological thriller from the bestselling author of Watching Edie

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Where the bloody hell is he, then?’

He shrugged. ‘Perhaps he’s just gone away for a wee while to clear his head.’

‘Clear his head? Why on earth would he need to clear his head?’

But Mac’s eyes slid away from hers and instead of replying he said, ‘I’ve called all his friends, but I guess he could be at his parents’ place. Have you tried there?’

The question made Clara pause. ‘No, not yet.’

‘Maybe you should check with them. It’s the first thing the police will do.’

Mac was right. His mum and dad’s house in Suffolk was the obvious place Luke would go – in fact she was surprised it hadn’t occurred to her before. She’d never known anyone as close to their parents as Luke. Perhaps the emails had rattled him enough to make him want to get out of London for a few days. But in that case, why hadn’t he told her?

Looking down at her phone, she hesitated. ‘What if he’s not there, though? You know what his mum and dad are like – they’ll be beside themselves.’

‘Aye, you’re not wrong there.’

She and Mac stared at each other, both thinking the same thing: Emily.

Luke never talked about his older sister and Clara only knew the bare facts: when she was eighteen, Emily had walked out of the family home and was never heard from again. He’d been ten years old at the time, his brother Tom, fifteen. He had told her a few months after they’d started dating, one night at his old place in Peckham, a shared flat off Queens Road in a dilapidated Victorian terrace, where at night they would lie in bed and listen to the music and voices carrying from the bars and restaurants squeezed into the railway arches across the street, trains thundering over the elevated tracks above.

‘And you’ve no idea what happened to her?’ she’d asked, astonished by his story.

Luke had shrugged, and when he’d spoken again there was a heaviness to his voice she’d not heard before. ‘No, none of us had a clue. She just walked out one day. Left a note saying she was leaving home, and we never heard from her again. It totally destroyed my family; my parents never got over it. Mum had a nervous breakdown and in the end it was better to never mention her. All the pictures of her got put away, everyone stopped talking about her.’

Clara had sat up, appalled. ‘But that’s awful! You were only ten, you must have wanted to talk about her, it must have devastated you and your brother too.’

The hand that had been stroking her leg paused. ‘We learnt it was better not to, I suppose.’

‘But … was there … I mean, weren’t the police involved?’

He shook his head. ‘She went of her own free will. I think that was the hardest part for my mum and dad – she left a note saying she was going, but no explanation as to why or where. My dad told me they hired a private detective to try and find her but it didn’t come to anything.’ He shrugged. ‘She completely vanished.’

And in that moment she’d understood something about Luke that had always puzzled her. Something she’d glimpsed hovering behind the laughter and the jokes, his need to be the life and soul of every party, a sorrow flickering barely there at the edges of him she hadn’t quite been able to put her finger on before.

‘What was she like?’ she’d asked softly.

He smiled. ‘She was ace. She was funny and sweet but kind of … fierce, you know? I was only ten, and I guess I’m biased, but I don’t think you meet many people like her. She was so passionate about stuff, she’d go off on all these rallies and marches, save the whale, women’s rights, you name it. Drove Mum and Dad mad because she’d never just stay still and get on with her school work. I was only a kid, but even then I admired her for it, how principled she was, how sure she was about what was right and wrong. And she was a free spirit, you know?’ He sighed and rubbed his face. ‘Maybe our house was too restrictive for her and she wanted her freedom. Who knows? Maybe that’s why she went.’

‘I’m so sorry,’ Clara had said quietly. ‘I can’t imagine how hard it must have been for you all.’

He got up, crossed the room to pull a book down from its shelf and handed it to her. It was a thin volume of children’s poems. T.S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. ‘She gave me this a few months before she left,’ he told her. ‘She used to read it to me when I was a kid. It was …’ he stopped. ‘Well, anyway. That’s kind of all I have left of her.’

Reverently, Clara had opened it and read aloud the message written on the flyleaf. ‘“For Mungojerrie, from Rumpelteazer. Love you Kiddo. Always, E xx” ‘Mungojerrie?’ Clara had queried, and he’d smiled.

‘They’re the names of the cats in one of the poems – her favourite one.’

He’d been silent for a while before saying, ‘Anyway, it’s all in the past now,’ and he’d taken the book from her hands and pulled her towards him and started kissing her again, to stop her questions, she’d sensed. Whenever she’d tried to bring Emily up after that, he’d simply shrug and change the subject until eventually she’d given up, though she’d found herself thinking about her often, the missing sister of her boyfriend who’d walked away from home one day, never to be heard from again.

Now, with sudden decisiveness she said to Mac, ‘I’m going to drive over there.’

His eyebrows shot up. ‘To Suffolk? How long will that take?’

She looked around for her keys and bag. ‘An hour and a half tops. At least I’ll be doing something. I can’t just sit here waiting for him, I feel like I’m going mad. And I think you’re right – I think that’s where he’ll be. He’s so close to his mum and dad. And if he has gone there because he’s freaked out by the emails, I’d prefer to talk to him face to face.’

‘OK,’ Mac said slowly, ‘but what if he’s not?’

She glanced at him. ‘Then I’ll call the police, which is another reason why I should warn Rose and Oliver first. Will you stay here in case he does come back?’

Mac nodded and patted his laptop bag. ‘Sure, I’ve a load of pictures to edit – might as well work here as anywhere else.’

She hesitated. ‘Will you call the hospitals too?’

‘Clara, I really don’t think anything …’

‘Please, Mac.’

He held his hands up in defeat. ‘OK, sure.’

As soon as Clara got into her car, she phoned her office, putting her mobile on hands-free, before setting off across town towards the M11. She was almost at the North Circular before her editor grudgingly accepted her explanation of ‘personal problems’ and agreed she could have the next day off. After that she phoned Lauren, who confirmed there’d still been no word from Luke all day. Finally she asked to be put through to the security desk where she reached George, the guard who’d been on duty the night before. He told her that Luke had left the building via the back entrance at around 7.30, that they’d had a brief chat about the football and there’d seemed nothing wrong. ‘You know Luke,’ he chuckled, ‘always got a smile on his face.’

As she drove through the London streets she thought about Luke’s parents. She remembered how nervous she’d been the first time he’d brought her to The Willows, his childhood home in Suffolk. Rose and Oliver had sounded so impressive; so very much larger than life – and so very different from her own mum and dad.

It had been a morning in late May. The house they drew up to stood alone, stark against the bleak beauty of the Suffolk landscape, the seemingly endless flat fields, the sky vast and blue and cloudless above them. Luke had led her around the side of the building through to a long and sweeping garden, its borders a carefully controlled riot of colour, a white lilac tree at its centre heavy with flowers that filled the air with their sweet powdery scent. ‘Wow,’ she’d murmured and Luke had smiled. ‘My mum’s pride and joy, you should see the parties she throws here every summer – the whole village comes along, it’s insane.’ And there, at the far end of the garden, kneeling at a flower bed, secateurs in hand, had been Rose. She’d stood up when she heard them approach, and Clara’s belly had dipped with apprehension. What would this woman, this cultured, educated, retired surgeon, think of her? Would she like her, think her good enough for her son?

But Rose had smiled, and walked towards them, and in that instant Clara had known everything would be OK. This slim, pretty, fresh-faced woman in a pink summer dress was not in the least intimidating. Instead, Clara had been bowled over by Rose’s charm, the way her eyes lit up when she smiled, the genuine warmth with which she’d hugged her, her infectious, enthusiastic way of talking. Rose had led her into the kitchen that first day and patting her hand had said, ‘Come and have a drink and tell me all about yourself, Clara, it’s so lovely to have you here.’

Oliver, Luke’s dad, had emerged from somewhere out of the depths of the house, a tall and bearded bear of a man, Luke’s features mirrored in his own, his son’s kindness and good humour shining from his almost identical brown eyes. He was a university lecturer, the author of several books on art history. Slightly shy, he was quieter and more reserved than his wife but Clara had warmed to him instantly.

In fact, she’d fallen in love with everything about the Lawsons that day: their beautiful, rambling house, the easy affection they’d showed one another, even the way they argued and joked, good-naturedly mocking each other’s flaws – Oliver’s messiness and tendency towards hypochondria, Rose’s bossy perfectionism or Luke’s inability to lose at anything without sulking. It was a revelation to Clara, who’d grown up in a house where even the smallest of perceived slights could lead to weeks of offended silence. She had been conscious, that first visit to The Willows, of the strangest feeling of déjà vu, as though she’d returned after a long absence to somewhere she’d once known well; the place where she was always meant to be.

On those early visits Clara would secretly, eagerly, look for signs of Luke’s lost sister, but never found any. Emily wasn’t in any of the framed photos in the elegant living room, and only Tom and Luke’s old preschool paintings were lovingly displayed on the kitchen walls, autographed in their childish scrawls. She had sounded like such a strong and vivid personality from Luke’s description, yet even in the small attic room that had once been hers, no trace of Emily remained. She was so carefully deleted from the fabric of her family that it somehow made her all the more present, Clara thought. What had happened to Luke’s sister, she brooded; why would someone leave this loving family home so suddenly, then vanish into thin air? The question fascinated her because, despite the Lawsons’ warm hospitality, the welcoming comfort of their beautiful home, she could feel the sadness that lingered there still, in the corners and the shadows of each room.

Over the following three years Clara would hear Emily’s name mentioned only once. It was at a birthday party for Rose, The Willows full to bursting with friends from the nearby village, ex colleagues of hers from the hospital, Oliver’s writer and publishing friends and what felt like the entire faculty of the university he taught at. Oliver had been extremely drunk, regaling Clara with an anecdote about a recent research trip when suddenly he had fallen silent, staring down at his drink, apparently lost in thought.

‘Oliver? Are you OK?’ she’d asked in surprise.

He’d replied in a strange, thick voice, ‘She meant the world to us you know, our little girl, we loved her so very much.’ And to her horror his eyes had filled with tears as he said, ‘Oh my darling Emily, I’m so sorry, I’m so very sorry.’ She had stared at him, frozen, until Luke’s brother Tom had appeared and gently led him away, murmuring, ‘Come on, Dad, time for bed now, that’s right, off we go.’

At last Clara left London behind and joined the M11. It should only take her another hour or so to reach Suffolk. Would Luke be there? She gripped the steering wheel tighter and pressed her foot on the accelerator. Surely he would – he had to be. Unbidden, the emails she’d read earlier came back to her – It’s going to be soon, Luke, your funeral’s going to be very soon – and she felt again the knot of fear tightening in her stomach.

She reached The Willows as the sun began to set. As she got out of the car and gazed up at the house, cawing jackdaws circled above the surrounding fields in the twilight sky. This moment of stillness before nightfall seemed to capture the place at its most magical. It was an eighteenth-century farmhouse, clematis and blood flower clambering over its red bricks, an ancient weeping willow shivering in the breeze. On either side of the low, wide oak door, crooked, crown-glass windows offered a glimpse into the beautiful interior beyond. It was a house out of a fairy story; enchanted and remote beneath this endless empty sky. She approached the door now, taking a deep breath before she knocked. Please be here, Luke, please, please, just be here.

She heard the familiar sound of their ancient spaniel, Clementine, bounding to the door, followed by the latch being raised. It was Oliver who opened it. He peered out at her, not seeming to recognize her at first, clearly wary to have someone appear out of the blue, they were so remote and alone out here. Eventually, his expression cleared. ‘Good Lord, Clara!’ He turned and called behind him, ‘Rose, it’s Clara! Oh do calm down, Clemmy! Come in, come in, what a lovely surprise. What on earth are you doing here?’

She glanced over his shoulder to the cosy glow of the room behind him and felt the house’s familiar pull. She caught the smell of something cooking and pictured Rose in the kitchen listening to Radio Four while she made dinner, a welcoming, irresistible scene of affluent domesticity, so different from the chilly semi-detached she’d grown up in in Penge. But before she could reply, Rose came running up behind him. ‘My goodness, darling, hello! Where’s Luke?’ She looked beyond Clara to the car, her expression pleased and expectant.

Clara’s heart sank. Shit. ‘He’s not with me, actually,’ she admitted.