По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

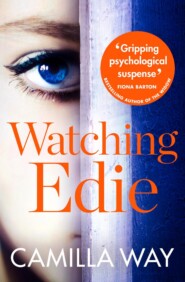

The Lies We Told: The exciting new psychological thriller from the bestselling author of Watching Edie

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Clara shook her head. ‘No.’

He nodded. ‘In most cases the missing person turns up within forty-eight hours. But due to the harassment Luke’s been receiving, we need to make sure there’s nothing more to this. I understand there’d been a letter … some photographs as well as the break-in a few months ago? Do you have them here with you?’

For the next ten minutes Clara went about the flat, gathering the various items that DS Anderson requested – Luke’s bank details, the names and numbers of his friends and family and place of work, a recent photograph, his passport and so on. She moved as if in a dream, stepping around DC Mansfield, who glanced at her apologetically as she conducted her own search, opening various cupboards and drawers. ‘What are you looking for?’ Clara asked when she found her scrutinizing the bathroom cabinet.

‘It’s standard procedure,’ she said, not answering her question. ‘I’m going to need something with Luke’s DNA, by the way. Did he take his toothbrush with him?’

Clara shook her head. ‘He didn’t take anything with him.’ She handed over Luke’s green toothbrush, leaving her own red one alone in its cup, and tried to fight the tears that sprung to her eyes.

When she returned to the living room she gave DS Anderson everything she’d collected and he nodded his thanks. ‘Luke left his mobile behind too,’ she said, handing it to him. ‘The code’s 1609.’ The sixteenth of September. Her birthday. She remembered how he’d smiled and said, ‘That way I’ll never forget.’ She watched as that, too, was efficiently deposited into a clear plastic evidence bag.

Anderson turned his attention to Mac. ‘And how about you, Mac? How long have you and Luke been friends?’

‘Eighteen years. Since we were eleven.’ Clara almost smiled at the way this giant Glaswegian was suddenly sitting up straighter, his knees pressed neatly together, meek as a kid in front of his headmaster.

‘And there was nothing about his behaviour recently that struck you as unusual?’

‘No … I don’t think so, no.’

Clara glanced at him. Was there something a little strange about the way Mac said that? The brief hesitation before he spoke, something slightly off about his tone? She couldn’t quite put her finger on it.

Twenty-five minutes after they arrived, the two officers got up to leave. ‘I think I have all I need for now,’ Anderson told them. ‘I’m going to talk to Luke’s parents and his employers next.’ He paused, consulting his notes. ‘Brindle Press? W1. Is that right?’ When Clara nodded he went on, ‘We’ll also look at any relevant CCTV footage, to see if we can trace his movements after he left work yesterday.’ He glanced at Mac. ‘And if you could both think about anything that might have happened in the last few weeks that could be relevant – any unusual phone calls, anything out of character he might have said to either of you, or any change in his usual behaviour …’

‘Yes, yes of course,’ Mac and Clara said together.

He nodded. ‘We’ll be in touch.’

After they left, Clara sank on to the sofa. ‘Jesus,’ she murmured. She put her head in her hands. ‘At least they’re taking it seriously, I suppose.’ When Mac didn’t reply she turned to find him standing with his back to her, gazing out of the window. ‘Are you OK?’ she asked.

He was silent for a while, and then she heard him mutter something to himself. She stared at him in bewilderment. ‘Mac? What’s the matter? What is it?’

He turned to face her. ‘Jesus, Clara, I’m so sorry.’

‘Sorry? What on earth for?’

He raked his fingers through his hair in agitation. ‘I really didn’t want you to find out like this. But it’s all going to come out now – the police are going to talk to everyone – his work, his friends; everyone, and I don’t want you to hear about it that way.’

‘For God’s sake, Mac! Hear about what?’

Mac closed his eyes for a moment. ‘Luke’s affair.’

The shock was like a body blow, knocking the air from her lungs and leaving her reeling. And when she was finally able to speak her voice was barely more than a whisper. ‘Affair? Who with?’

‘A girl from work. Her name’s Sadie. I think she’s …’

On the ads team. Blond hair, legs to her armpits. Barely twenty. ‘Yeah, I know who she is.’ She felt strangely incapable of reaction, as if the information wouldn’t quite penetrate her brain. ‘How long?’

‘A few weeks, maybe a couple of months. But it finished ages ago. Listen, Clara—’

She cut across him, ‘A couple of months? And is he … does he love her?’

His reply was emphatic. ‘God, no! No, of course not. He loves you, Clara, I know he does.’

She gave a weak laugh. ‘Clearly.’

‘It was just … oh God, Clara, I’m so sorry.’

She stared at him. ‘But he asked me to move in with him! Why? Why do that if you’re shagging someone else?’

‘He knew Sadie was a huge mistake. He realized it was you he wanted.’

She nodded. ‘Great. Lucky me.’

A silence. ‘Why the fuck didn’t you tell me, Mac?’ she asked him quietly. She realized she felt almost as betrayed by him as she did by Luke, almost as hurt by her friend’s deceit as by the man who was supposed to be in love with her. She thought of all the times she, Luke and Mac had spent together, when she’d been oblivious to the secret they shared, and her cheeks burned with anger and embarrassment.

‘I—’

She glanced at him, her voice suddenly hard. ‘Don’t tell me. Because you’re his best friend. Lads sticking together, right? Some stupid fucking boy code?’

His face was a picture of misery. ‘Clara, listen to me …’

She waved his words away. ‘Does everyone know?’ She thought of Luke’s large circle of friends – people they socialized with together, met up with at the pub, invited round for dinner, and her humiliation deepened. ‘All of you, all his mates?’

‘No! God, I don’t know. He felt awful about it. He didn’t know what to do, he was in absolute bits …’

It was then she remembered something. ‘That’s what you meant about him going away to clear his head,’ she said, and the flicker in Mac’s eyes confirmed it.

‘At first I thought maybe he was with her. But I called her and he wasn’t. Then I thought maybe he did go away somewhere to try and sort himself out, get his head straight, but … I don’t think so. It doesn’t add up – not telling work, his parents, me, not taking any of his stuff … and the thing with Sadie ended ages ago.’

From outside on the street Clara heard the jingling crash of crates of beers being delivered to the bar on the corner. They sat and listened to it, a sound she associated with summer, with sitting outside pubs on sunlit pavements with Luke, with being happy.

‘Clara? Are you OK? I’m sorry. I’m so fucking sorry.’

She looked at his anxious face and suddenly felt so tired she could barely stand. She sank back on to the sofa. ‘Just go, Mac,’ she said quietly. ‘Just go the fuck home now, will you?’

7 (#ulink_15b144bc-158c-5605-bab1-faa8283f232c)

Cambridgeshire, 1988

There was a local woman, a childminder named Kathy Philips, who occasionally took care of Hannah for me when I needed a break. She was, in hindsight, a bit slack; her home was haphazard, she had four children of her own, plus at least one other mindee whenever I dropped Hannah off. But she was a kind, no-nonsense sort, and, most importantly, she was willing – by then Hannah’s reputation had spread throughout our village; there weren’t a lot of people willing to look after her. I was desperate, I’ll admit.

I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised that Hannah did what she did. She had told me that morning she didn’t want to go: ‘They’re stupid and boring and their house smells of wee,’ was I think how she put it. So this, I expect, was her way of punishing me.

I’ll never forget the fury in Kathy’s voice when she called. ‘Come and pick your daughter up right now,’ she spat, before slamming the phone back down. As I drove over there I mentally ran through the possibilities. Attacked one of the other kids? Stolen something? But no, it was far worse than either of those things. Kathy was waiting for me at her door when I pulled up and the expression on her face made my blood run cold. ‘She set fire to my son’s bedroom,’ she told me through gritted teeth.

There was no coming back from that. There was no sweeping that under the carpet – no pretending she’d grow out of it, that it was merely some dreadful phase. Hannah had taken some matches from Kathy’s handbag, sneaked upstairs and made a pile of Callum’s books, then set fire to them. Kathy, luckily, had smelt the smoke before it had spread too far – but not before she’d burned a large brown hole in the carpet. I hate to think what would have happened if it had been allowed to take hold.

‘Callum was being annoying,’ Hannah shrugged, when I asked her why she’d done it. By this time she was seven years old.