По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

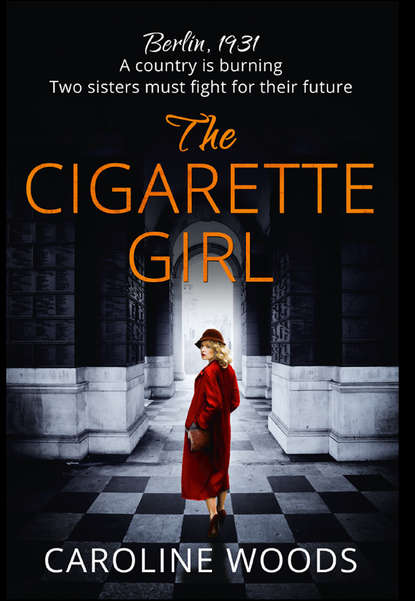

The Cigarette Girl

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

At first, Remy had found her rude. And when he heard the accent, the one they’d mocked and cursed on the battlefield, he’d almost left her alone. But then he noticed how her long-boned hands—the nails painted red, but shredded, chipped—shook on the Formica, her cup rattling against its white saucer. “Just let me finish my coffee,” he said. “We don’t have to talk.”

At this, she seemed to relax. After a while she cleared her throat. “From where I came . . .” she began, and he flinched again at the accent, “people have cup of coffee and cake in afternoon, then, walk. You will walk with me, in the park?” She smiled, her teeth crooked and gapped, and he realized then how lonely she was.

That first day, she taught him a word in German: Waldeinsamkeit, the sensation of being alone and content in the woods. “But you aren’t alone,” he protested as they strolled through Piedmont Park, a few blocks from traffic. “I’m spoiling it.” And she smiled at him and told him it was sometimes possible to be alone together.

As a young child, Janeen would request this bit of family lore at bedtime, brushing aside Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty in favor of her parents’ romance. But as she grew, questions surfaced. Why had her mother been so sad? Why did she work in a factory? Where did she go before Atlanta?

Her father’s answers were short: because she missed the people she had to leave in Germany; because she wanted to help America win the war; New York City. Ask your mother, he’d say when Janeen pressed for details. But her mother never told the story.

Lying on the floor of the spare room, Janeen tried reading a dime-store mystery for a while to take her mind off her parents. The words blurred on the page. Finally, at two, she plunged into the heat to get the mail. The envelopes scorched her hands a little, like cookies from the oven. She leafed through catalogs and bills; at the back of the stack was a letter addressed to Anita Moore. There was no return address, but the stamp had been canceled in Manhattan.

Something about it sent a shiver down her arms. She took the envelope up to the music room, where her record still droned, two male voices harmonizing sweetly. She sat on the round rug, staring at the envelope.

It was the handwriting, she realized after a minute, and the goose bumps spread to her scalp. It looked exactly like her mother’s. It was as if she’d sent a letter to herself.

She hesitated for another second, then turned it over and ripped open the flap. The letter was written in German. She nearly folded it and put it back into the envelope, but she could make out the first line, and the second—what else were all her years of German class for?—and before she knew it, she’d read the whole thing.

Dear Anita,

It is only fair that I begin with an introduction. Though I go by Margaret now and use my ex-husband’s last name—Forsyth—I am the girl you knew as Grete Metzger. Berni’s sister. I will understand if you stop here and throw this letter away.

By now you will have heard the news about Henry Klein, the one they are saying is Klaus Eisler. His resurfacing will no doubt have taken you back to the past. In remembering the Eislers, you perhaps have remembered me. This is why I felt I must write. For far too long I have let Klaus and his actions speak for me. It is time I speak for myself.

I write to beg forgiveness. It’s too little, too late, I know, but since I cannot tell Berni—and many others—that I am sorry for what I’ve done, I will tell you.

Every day I’m consumed with regret. I consider small decisions, small mistakes. When I stayed at St. Luisa’s instead of climbing into Sonje’s car. When I shouted you out of the Eislers’ courtyard instead of accepting your apology. When I found your address I faced another decision. Would I write to Anita and explain, burden her with my apology, or remain silent? Would I ask what happened to Berni or stay forever in the dark? I know it is no good to open old wounds, but I choose to ask.

All these years I’ve been able to think of nothing but Berni. I wonder if you feel the same. You knew her better than I did. You were her true sister. There is so much I would tell her if she were alive. I’d tell her I loved her, first, and I would do my best to explain what happened between Klaus and myself.

Please accept my gratitude, Anita, for all you did for Berni that I couldn’t. If you are willing to correspond, I’ll write again. If not, I will disappear.

Should we never speak again, I wish you the very, very best.

Grete

The record player whirred and whirred; it had reached the end of Side A.

Janeen’s entire body tingled. There it was, in black ink: Klaus Eisler, also known as Henry Klein. The man in the newspaper. The man Anita had pretended not to know.

Janeen felt sick. Why would her mother have lied about knowing him—an officer in the SS? Had he been her mother’s boyfriend? Or worse, had he been her—Janeen’s stomach lurched—colleague? She’d heard her mother say before, in passing, that the Nazis had been able to seize the minds of all kinds of people. What if she’d been talking about herself?

Janeen sat up shakily. She unwrapped a root beer barrel from a cut-glass bowl on the bookshelf and sucked it to think. She read the note again, then a third time. Anita had stood in the Eislers’ courtyard. She’d been a “true sister” to someone named Berni. Janeen found herself feeling oddly jealous. Her mother had lived an entire life without her, one she knew absolutely nothing about.

She bit the candy in half, grinding it smooth against her molars, and tore a page from her notebook. She wrote very little, so that she would not reveal her limited German:

Dear Grete,

I will listen. That is all I can promise. I’ll look for your letter.

Anita

Janeen read it over and nodded. It was the only way to find out the truth—she couldn’t ask her mother. This woman would respond and confirm that Anita had been no Nazi. Of that Janeen felt certain. Almost certain.

This was how she justified sealing the envelope. Before she could change her mind, she ran the reply down to the mailbox. She waited, breathing heavily, until she saw the mailman loop back around, drawn by the raised red flag.

Part II (#ulink_e6d23e27-2c52-54e0-8c66-cb4e02b318ee)

Berlin, 1932–1933

We take them [the youth] immediately into the SA, SS, et cetera, and they will not be free again for the rest of their lives.

Adolf Hitler

Grete, 1932 (#ulink_e8036860-f40e-5069-bef3-e6e59e319111)

For over a year Grete lived at St. Luisa’s without Berni, and in that time she allowed the other girls to stream around her as a river wears down a stone. It was easier not to talk, not to risk entering conversations she might not be able to hear. By the summer of 1932, she knew the other girls had forgotten she existed. They thought of her as inanimate, a bench or forgotten hymnal.

The plan had been for Berni to find an apartment for them to live in together, and that would have happened long ago, according to Berni, if it weren’t for the Depression. “I can barely make enough money selling cigarettes to support myself,” Berni said on her most recent visit, avoiding Grete’s eyes. “In St. Luisa’s, at least you know you will be fed every day.”

Sister Josephine helped facilitate their meetings. Every month or two she sent Grete on an errand, to get soap flakes or cherry juice for her gout. Like clockwork, Berni would appear outside the store. How she and Sister Josephine communicated was a mystery.

“If you have so little money, why are you smoking?” Grete snapped. Her sister’s excuses were growing tiresome. Sometimes she wondered if Berni was having too much fun to burden herself with a deaf little sister.

The changes in Berni disturbed Grete. First her hair had been chopped to chin length. Then she began wearing ties. She used suspenders to hold up trousers made for men. Her hair became shorter and shorter, combed wet like a boy’s, and her laugh changed; it became deep, hoarse, a smoker’s laugh. Whatever had caused this metamorphosis, it had nothing to do with Grete, and she both hated and feared it. The same unease she had felt with Sonje Schmidt, she felt around Berni now.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: