По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

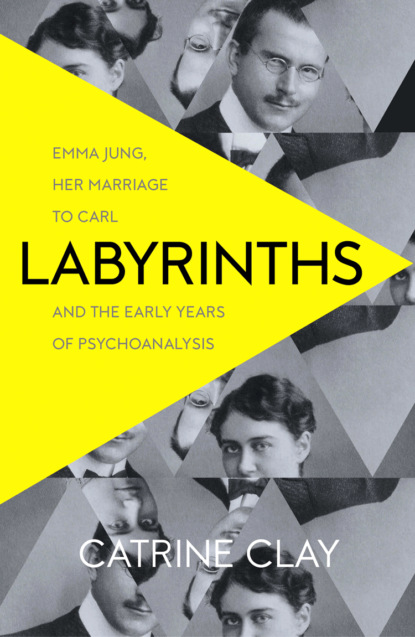

Labyrinths: Emma Jung, Her Marriage to Carl and the Early Years of Psychoanalysis

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Carl and Emma easily fell into the roles of teacher and student. Carl had already completed five years of medical studies and embarked on the work and profession that would occupy him for the rest of his life. At this time he was working on his doctoral dissertation, ‘On the Psychology and Pathology of So-called Occult Phenomena’, investigating the uncharted world of the unconscious through the evidence he had gathered during Helly’s seances at Bottminger Mill. Herr Professor Freud in Vienna had just published a book called The Interpretation of Dreams, which investigated the unconscious from a different angle, the hidden meaning of dreams, which had often filled the pages of literature but had never yet been scientifically investigated, and Carl had been deputed by Bleuler to read it and present his findings to the Burghölzli staff at one of their evening meetings. As if he didn’t already have enough paperwork to do. But this was different. This was the new world, just waiting to be discovered.

To Emma, Carl was worldly and sophisticated and, as his friend Albert Oeri described, he was a mesmerising talker. So Emma might have been surprised to discover that her fiancé had absolutely no experience of women. ‘He didn’t think much of fraternity dances, romancing the housemaids, and similar gallantries,’ recalled Oeri, making Carl sound like a bit of a prig. He did bring Luggi, Helly’s older sister, to some dances, but Oeri only remembered one occasion when Carl was really smitten, at another fraternity dance, with a young woman from French-speaking Switzerland, at which point he began to behave very oddly indeed. In fact, if Oeri had not been such a reliable witness, one would wonder at the veracity of the story. ‘One morning soon after,’ Oeri wrote, ‘he entered a shop, asked for and received two wedding rings, put twenty centimes on the counter, and started for the door.’ Presumably the twenty centimes were by way of a deposit. When the owner objected, Carl gave back the rings, took his money and left the shop ‘cursing the owner, who, just because Carl happened to possess absolutely nothing but twenty centimes, dared to interfere with his engagement’.

With anyone else you might think this was some kind of student prank, but not with Carl, hovering precariously between two personalities and having no idea how to handle such a situation. Afterwards ‘Carl was very depressed,’ said Oeri. ‘He never tackled the matter again, and so the Steam-Roller remained unaffianced for quite a number of years.’ Until he met Emma, in fact, and persuaded her to marry him.

But Emma had a secret of her own. When she was twelve her father started to lose his sight. Soon he could no longer read for himself, and Emma, the studious one, was deputed to sit and read out loud to him: newspapers, magazines, books, business matters brought over from the factory and foundry nearby, so she became quite knowledgeable in financial matters and the handling of accounts. Later, as his condition worsened, plans for the redevelopment of the Ölberg estate were made for him in Braille. It was hard for Emma, not least because her father was a difficult, sarcastic man – a trait which got worse with age and the advance of his illness. Harder still was the fact that the cause of his blindness had to be kept secret, such was the shame and stigma attached to it: Herr Rauschenbach had syphilis. According to the family, he had caught the disease after a business trip to Budapest, presumably from a prostitute. Bertha had decided not to go with him on that occasion because she felt the two little girls were too young to be left alone with the children’s maid. Had she gone, everything might have been different. It was a tragedy for the family, and photographs of Emma during her teens show a shy, round-faced, podgy girl, surely feeling the stress of the family secret. She was trying her best to help her mother with this awful burden as her father became more and more bitter and desperate, shut away from the world in his room upstairs. It robbed Emma of her sunny nature, making her too serious for her age.

Albert Oeri remembered visiting the Jung household not long before Pastor Jung died and described how Carl, aged twenty, carried his father ‘who had once been so strong and erect’ around from room to room ‘like a heap of bones in an anatomy class’. Emma sat at her father’s side reading to him as he went blind, bitter and half mad. There was not much to choose between them.

By the end of the nineteenth century doctors were finally on the verge of finding a cure for syphilis, but not soon enough for Herr Rauschenbach. By 1905 Fritz Schaudinn and Erich Hoffmann in Berlin had identified the causative organism, the microbe Treponema pallidum, and by 1910 Dr Paul Ehrlich, director of the Royal Prussian Institute of Experimental Therapy in Frankfurt, developed the first modestly effective treatment, Salvarsan, though it was not until the discovery of penicillin in the 1940s that a cure was certain. In the 1890s the treatment still relied on the use of mercury, which could alleviate the condition if caught early enough though the side effects were extremely unpleasant, and it was not a cure. Syphilis, highly infectious and primarily transmitted through sexual contact, had stalked Europe for centuries, causing fear and dread and giving rise to a great deal of moralising about the virtues of marriage. The symptoms were horrible, the first signs being rashes and pustules over the body and face, then open suppurating lesions in the skin, disfiguring tumours and terrible pain, only alleviated by regular doses of morphine. Some of the most tragic cases were those of unsuspecting wives infected by their husbands, in turn infecting the unborn child. Wet nurses were vulnerable, either catching it from the child, or, already infected themselves, passing it on to the child instead. To make matters worse for families like the Rauschenbachs, society was hypocritical about syphilis. Everyone knew about the disease but it was not talked about, except in the medical pamphlets read in the privacy of a doctor’s surgery: ‘The woman must submit to her husband – consequently, whereas he catches it when he wants, she also catches it when he wants! The woman is ignorant . . . particularly in matters of this sort. So she is generally unaware of where and how she might catch it, and when she has caught it she is for a long time unaware of what she has got.’ Another pamphlet concentrated on women of the lower classes, unwittingly revealing a further hypocrisy of the times: whilst the bourgeois woman was seen as the victim, the working-class woman, not her seducer, or client if she was a prostitute, was to blame: ‘The woman must be told . . . Every factory girl, peasant and maid must be told that if she abandons herself to the seducer then not only does she run the risk of having to bring up the child which might result from her transgression, but also that of catching the disease whose consequences can make her suffer for the rest of her life.’

In Vienna, Sigmund Freud was investigating the psychological effects of syphilis on the next generation, finding that many of his cases of hysteria and obsessional neurosis, such as his patients ‘Dora’ and ‘Rat Man’, had fathers who had been treated for syphilis in their youth. It is possible that Bertha Rauschenbach was keen on Carl Jung as a suitor for Emma not only because she could see how well suited they were, but because Carl had just completed his medical studies and could help with the treatment of her husband’s illness, in secret, in the privacy of their own home. And she was no doubt relieved to realise how little experience her future son-in-law had had with women.

Meanwhile Carl was working at the Burghölzli, putting his father, who had died ‘just in time’ as his mother said, behind him. But he could not leave Personality No. 2 behind. Years later his friend and colleague Ludwig von Muralt, the other doctor at the Burghölzli when Carl arrived, told him that the way he behaved during those first months was so odd people thought he might be ‘psychologically abnormal’. Jung himself described experiencing feelings of such inferiority and tension at the time that it was only by ‘the utmost concentration on the essential’ that he managed not to ‘explode’. The problem was partly that Bleuler and Von Muralt seemed to be so confident in their roles, whereas he was completely at sea in this strange new world of the institution, and partly because he felt deeply humiliated by his poverty. He had only one pair of trousers and two shirts to his name and he had to send all his meagre wages back to his mother and sister, still living on charity at the Bottminger Mill. The humiliation was accompanied by a general feeling of social inferiority, heightened by the fact that Von Muralt came from one of the oldest and wealthiest families of Zürich.

They were the same feelings which had often plagued Carl in the past and his solution was the same: to withdraw into himself and become what he called a ‘hermit’, locking himself away from the world. When he was not working, he read all fifty volumes of the journal Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie, cover to cover. He said he wanted to know ‘how the human mind reacted to the sight of its own destruction’. He might have used his own father as an illustration. Or himself during those first months of 1901 after Emma had refused his hand in marriage, perhaps the real reason why he was so distressed, when his confident Personality No. 1 disappeared into thin air along with all his hopes and dreams, and he was close to a mental and emotional breakdown, as he had been in the past and would be again in the future.

The crisis was extreme. But then, quite suddenly, at the end of six months, he recovered. In fact, he swung completely the other way, the inferior wretch replaced almost overnight by the loud, opinionated, energetic Steam-Roller of old. Once betrothed and sure of Emma’s love, Carl was able to take life at the Burghölzli at full tilt, with the kind of energy which left others breathless. No one could fail to notice it, but no one knew the reason why, because no one knew where he went every Sunday on his day off.

Not knowing of Carl’s extreme crisis of confidence, Emma remained dazzled by his love, hardly able to believe it was true. She worried that she was a boring companion as she recounted small details about her mundane week – the riding, the walks by the Rhine, the family visits, her father’s deteriorating health, the musical evenings which her mother liked to host at Ölberg. The best moments were when they discussed the books she’d been reading, which gave her week its shape and purpose, enabling her to be ‘herself’ in a way which would otherwise have eluded her. To her joy Carl was delighted by her progress, always encouraging her to do more. And to her relief she soon discovered he was not in the least interested in having a bourgeois wife who thought of nothing but home and children and life within the narrow confines of Swiss society. Every day she waited for the postman, struggling up the hill to Ölberg on his bicycle, bearing another letter from Carl addressed to ‘Mein liebster Schatz!’ – my darling treasure – long letters, filled with Burghölzli news, ideas and suggestions for further reading, and telling her how much he loved her. And every Sunday, as Carl got to know Emma better, he found that beneath the shyness and seriousness there hid another Emma: one with a lively sense of humour, who could laugh and laugh. And who better to make her laugh than Carl?

The Burghölzli at the turn of the twentieth century under the directorship of Bleuler was a remarkable institution rapidly gaining an international reputation. At a time when most asylums simply removed the insane from society, locking them up, often for whole lifetimes, the Burghölzli offered treatment of various kinds and tried, as far as possible, to show the patients consideration and respect. Jung himself describes the situation:

In the medical world at the time psychiatry was quite generally held in contempt. No one really knew anything about it, and there was no psychology which regarded man as a whole and included his pathological variations in the total picture. The Director was locked up in the same institution with his patients, and the institution was equally cut off, isolated on the outskirts of the city like an ancient lazaretto with its lepers. No one liked looking in that direction. The doctors knew almost as little as the layman and therefore shared his feelings. Mental disease was a hopeless and fatal affair which cast its shadow over psychiatry as well . . .

Soon after Jung joined the staff numbers increased to five doctors, and as far as Bleuler was concerned five was a luxury; before he took the job of director of the Burghölzli in 1898 he had spent thirteen years as director of the lunatic asylum on the island of Reichenau, where there were over 500 inmates with only one trained medical assistant.

Eugen Bleuler was a remarkable man. Coming from Swiss peasant stock, he was the first of his family to attend university, and, much like Jung, he was drawn to this new branch of medicine because he had experience of mental illness in his own family. His sister, Pauline, was a catatonic schizophrenic and after Bleuler married in 1901 she lived with him, his wife and their eventual five children in a large apartment on the first floor of the Burghölzli. Bleuler had trained with some of the most progressive practitioners of the age, including Dr Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, where Sigmund Freud also spent time. Charcot was first and foremost a neurologist concerned with the functions and malfunctions of the brain, demonstrated with a showman’s flair to the hundreds of students who flocked to his lectures from England, Germany, Austria and America. He followed his patients’ progress throughout their lives and when they died he examined their brains under the microscope, making early diagnoses of Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease and Tourette’s. But it was his patients suffering from hysteria who interested him most and brought him his greatest fame. The fashionable ‘treatments’ at the time for hysteria were ‘animal magnetism’ and hypnotism, each requiring a doctor with special ‘intuition’. In animal magnetism the doctor passed his hands over the patient to release the vital fluid or energy which had supposedly become blocked. In hypnotism the doctor took control of the mind, providing the most dramatic demonstrations as patients fell into trances and spoke in strange voices. When Eugen Bleuler continued his training under Auguste Forel at the Burghölzli in the early 1880s, hypnotism was one of the main treatments and Forel had his own ‘Hypnosestab’, a wand with a silver tip which he used with some success on obsessives and neurotics as well as hysterics. But his greatest success was with alcoholics. The Burghölzli was then, and remained when Bleuler took over from Forel, an institution which held strictly to the virtues of abstinence. Drink was one of the worst afflictions of the age and asylums were full of chronic cases who were contained whilst ‘inside’, but, without a vow of abstinence, soon reverted to old habits once they left.

All this Carl explained to Emma in his letters, or on their Sundays in the drawing room at Ölberg, or on their afternoon walks high up in the meadows above the house, up to ‘their’ bench by the edge of the forest beyond. Later Emma confessed she only understood half of it at the time. Apparently Bleuler was continuing the progressive methods he had started to develop at Reichenau: staff lived amongst the inmates, eating with them at the same tables and socialising with them in their spare time. His theory of affektiver Rapport, listening with empathy, was the guiding principle. There was also a great emphasis put on cleanliness. Inmates were helped to wash thoroughly, in spite of a shortage of baths and bathrooms, and to keep their clothes in good order; likewise their beds, a dozen on each side of a ward, which were kept neat, the heavy feather covers hung out of the windows every morning to air and the mattresses regularly turned. The patients were kept occupied, Herr Direktor Bleuler believing that physical activity was good for the distraught mind. The kitchen gardens lay beyond the walls of the asylum extending down the slopes and provided all their vegetables and fruit, which were brought fresh to the kitchens every day. The dairy produced the milk and cheese. Hens provided the eggs. The laundry kept inmates busy washing and starching and ironing. The Hausordnung kept the building spick and span, smelling of floor polish and soap. There were workshops: woodwork and wood-chopping for the tiled stoves in winter, sack-making, silk-plucking, sewing, mending, knitting. The place was to all intents and purposes self-sufficient and the food, for an institution, was good: always a soup for the midday meal followed by meat and vegetables, with soup and bread again for the evening meal along with a piece of cheese or sausage. The patients were divided into three categories and while third-class patients did not eat as well as the first-class (private) ones, it was still a better standard than at most asylums. In the evenings there were card games, reading, concerts; sometimes the patients produced an entertainment, sometimes lectures were put on, and at the weekends there were occasional fetes and dances for those willing and able. Jung was put in charge of social events as soon as he arrived. He hated it.

To keep things going day to day there were seventy Wärters, male and female helpers in long white aprons and starched white collars, the men in trousers, shirt and tie, the women in long dark skirts and starched white caps. Like the doctors they lived on the premises, but unlike the doctors they had no quarters of their own. They slept on the wards or in the corridors, on wooden camp beds put up for the night, the women in the women’s section, the men in the men’s. The only exception was the Wärters in charge of the ‘first-class’ patients, who would sleep in the patient’s private room. This was a great privilege because not only was there some peace and quiet but the private patient was allowed candles in the room at night, or even an oil lamp if their behaviour was good enough and they were no danger to themselves or others. It was an eighty-hour week and the pay was low: 600 Swiss francs per annum for the male Wärters, a hundred francs less for the women. But board and lodging was all found, so the rest could be saved.

Carl’s day started at 6 a.m. and rarely finished before 8 p.m., after which he would go up to his room to write his daily reports, work on his dissertation, and compose his daily letter to Emma. There was a staff meeting every morning, after a breakfast of bread and a bowl of coffee, ward rounds morning and evening, an additional general meeting three times a week to consider every aspect of the running of the institution, and at least once a week a discussion evening, which, by the time Carl joined, was already well versed in the writings of Freud. Once into his stride there was no stopping Herr Doktor Jung, and his sheer brilliance soon singled him out. Bleuler’s affektiver Rapport was exactly the kind of treatment he himself believed in: listening acutely and with empathy to the apparent babblings of inmates with dementia praecox, or the outbursts of hysterics and the circular repetitions of obsessive neurotics. Carl was fascinated by the chronic catatonics who had been at the Burghölzli for as long as anyone could remember, including the old women incarcerated since they were young girls for having illegitimate children, who no longer knew who they’d once been.

Carl could listen to his patients for hours, taking notes, catching clues, watching how the mind worked. The Burghölzli was known for its progressive research, and inmates demonstrating interesting symptoms were the willing, and unwilling, guinea pigs – ushered into the room or lecture theatre for the doctor to examine, question and offer a diagnosis. It was a fine apprenticeship for Carl, as he himself admitted. He had little interest in the patients who were there with TB or typhus, and he could not bear the routine work, the meetings and the administration, to which he rarely gave any proper attention. But the old lady who stood by the window all day waiting for her long-lost lover, or the schizophrenic who talked crazily about God – that was a different matter altogether. Here his Personality No. 2 came into its own, working hand in hand with No. 1. ‘It was as though two rivers had united and in one grand torrent were bearing me inexorably towards distant goals,’ he later wrote. Bleuler soon saw that Herr Doktor Jung, with his fine intuition on the one hand and his brilliant mind on the other, understood the inmates like no one else.

Carl’s listening was made more effective by Bleuler’s insistence that everything be conducted in Swiss dialect, not the High German which doctors normally used, and which effectively meant no communication since most inmates could not understand High German, and even if they could, it caused such a social gulf between doctor and patient that the patient felt browbeaten. When speaking High German, Carl retained his broad Basel accent, something which had humiliated him at grammar school, but no longer. Now he learnt all the other regional Swiss dialects as well because at the Burghölzli it was expected that the doctor should adapt to the patient, not the other way round, an idea generally held as odd and even dangerous by the vast majority of the medical profession. Besides, without it Jung could do no useful research.

On Sundays he retold the patients’ stories to Emma, shocking her, entertaining her, keeping her spellbound. Stories about women in the asylum held a special fascination for her, such as the woman in Carl’s section who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Jung disagreed with the diagnosis, thinking it was more like ordinary depression, so he started, à la Freud, to ask the woman about her dreams, probing her unconscious. It turned out that when she was a young girl she had fallen in love with ‘Mr X’, the son of a wealthy industrialist. She hoped they would marry, but he did not appear to care for her, so in time she wed someone else and had two children. Five years later a friend visited and told her that her marriage had come as quite a shock to Mr X. ‘That was the moment!’ as Jung wrote in his account of it. The woman became deeply depressed and one day, bathing her two small children, she let them drink the contaminated river water. Spring water was used only for drinking, not bathing, in those days. Shortly afterwards her little girl came down with typhoid fever and died. The woman’s depression became acute and finally she was sent to the Burghölzli asylum. Jung knew the narcotics for her dementia praecox were doing her no good. Should he tell her the truth or not? He pondered for days, worried that it might tip her further into madness. Then he made his decision: to confront her, telling no one else. ‘To accuse a person point-blank of murder is no small matter,’ he wrote later. ‘And it was tragic for the patient to have to listen to it and accept it. But the result was that in two weeks it proved possible to discharge her, and she was never again institutionalised.’

Love, murder, guilt, madness. Emma had never heard stories like it. Nor had she ever considered the powerful workings of the ‘unconscious’. But she was intelligent and well read. She knew all about Faust’s pact with Mephistopheles, Lady Macbeth’s guilty sleepwalking, and Siegfried, the mythical hero. Now she was beginning to realise that this ‘unconscious’ was the key to the hidden workings of the mind and could be accessed in various ways, then used as a tool to cure the patient. By the time of their secret betrothal Emma was helping to write up Carl’s daily reports, learning all the time. If these years were the beginning of Carl Jung’s career, they were the beginning of something for Emma too.

Meanwhile Jung was trying, between his eighty-hour week and his social duties, to finish his dissertation on the ‘So-called Occult Phenomena’. There had been a revival of interest in the occult at the end of the nineteenth century, people using Ouija boards and horoscopes, having seances, delving into magic and the ancient arts, and reporting strange paranormal occurrences. Carl was used to such things from his mother’s ‘seer’ side of the family, like the time when a knife in the drawer of their kitchen cupboard unaccountably split in two, or the times when his mother spoke with a strange, prophetic voice. But what interested Jung the doctor was the way the occult provided another route to the hidden world of the unconscious, more psychological than spiritual. Cousin Helly was probably a hysteric, he now concluded, a young girl falling into trances to get attention. In fact Helly’s mother had become so worried about the way the trances and the voices were dominating her life that she had packed her off to Marseilles to study dress-making, at which point Helly’s trances stopped, and she became a fine seamstress.

Jung presented his dissertation to the faculty of medicine at the University of Zürich in 1901 and it was published the following year. The Preiswerk family, reading it on publication, were distressed. After a general introduction about current research on the subject, Jung concentrated on one case history: Helly Preiswerk and her seances at Bottminger Mill, referring to her, by way of thin disguise, as Miss S. W., a medium, fifteen and a half years old, Protestant – that is, instantly recognisable by anyone who knew the family. She was described as ‘a girl with poor inheritance’ and ‘of mediocre intelligence, with no special gifts, neither musical nor fond of books’. She had a second personality called Ivenes. One sister was a hysteric, the other had ‘nervous heart attacks’. The family were described as ‘people with very limited interests’ – and this of a family who had come to the rescue of his impoverished mother and sister. It showed a side of Carl which Emma would have to deal with often in the future: a callous insensitivity, driven perhaps by what he himself admitted was his ‘vaulting ambition’. But as far as the faculty of medicine at the University of Zürich was concerned, it was a perfectly good piece of research, fulfilling the aims Jung expressed in his clever conclusion: that it would contribute to ‘the progressive elucidation and assimilation of the as yet extremely controversial psychology of the unconscious’.

The most telling thing about the dissertation is the dedication on the title page. It reads: ‘to his wife Emma Jung-Rauschenbach’. Given the dissertation was completed in 1901 and published in 1902, the dedication precedes the event of the marriage by a good year. Whatever was Carl thinking? What is the difference between ‘my wife’, which Emma was not, and ‘my betrothed’, which she was. It suggests Carl was desperate to claim Emma for himself, fully and legally, a situation which mere betrothal could not achieve. Emma was the answer to all Carl’s problems: financial – certainly – but equally his emotional and psychological ones. He needed Emma for his stability in every sense, and he knew it.

Carl and Emma’s wedding was set for 14 February 1903, St Valentine’s Day. Buoyed up and boisterous, Carl became increasingly impatient and intolerant of the ‘unending desert of routine’ at the Burghölzli. Now he saw it as ‘a submission to the vow to believe only in what was probable, average, commonplace, barren of meaning, to renounce everything strange and significant, and reduce anything extraordinary to the banal’. Given Bleuler’s achievements at the asylum this was high-handed Carl at his worst. The fact is, he was fed up. He wanted to take a sabbatical, to travel, to do things he had never been able to do before. And he wanted to do it before he married Emma. Because he had no money of his own, his future mother-in-law happily offered to fund it. In July 1902 Jung submitted his resignation to Bleuler and the Zürich authorities, and by the beginning of October he was off, first to Paris, then London, for a four-month pre-wedding jaunt. Bleuler, knowing nothing of Jung’s secret betrothal to Fräulein Rauschenbach, must have been angry and non-plussed. How would Herr Doktor Jung afford it? How could he manage without a salary? And what about his poor mother and sister?

Emma and her mother meanwhile started the lengthy process of preparing for the wedding – the dress itself, the veil, shoes, bouquet, trousseau, church service, flowers, guest list, menu for the wedding banquet, and the travel arrangements for the couple’s honeymoon. Emma’s father’s health must have caused some heartache: already parlous, it had taken a turn for the worse. He knew about his daughter’s betrothal to Carl now, but what to do about the wedding? It was a terrible dilemma for Emma who had, over the years, watched her father’s decline in horror and shame, and now he would not be able to attend the ceremony, or walk her up the aisle, or give her away.

Before leaving the country Carl had to complete his Swiss army military service, an annual duty for all Swiss males between the ages of twenty and fifty, in his case as a lieutenant in the medical corps. But then he was off, first paying a visit to his mother and sister in Basel on his way to France. From Paris he wrote daily letters to Emma, and separately to her mother too, giving them all the news: he lived cheaply in a hotel for one franc a day and worked in Pierre Janet’s laboratory at the Salpêtrière, attending all the eminent psychologist’s lectures. He had enrolled at the Berlitz School to improve his English and started reading English newspapers, a habit he retained all his life. He went to the Louvre most days, fell in love with Holbein, the Dutch Masters and the Mona Lisa, and spent hours watching the copyists make their living selling their work to tourists like himself. He walked everywhere, through Les Halles, the Jardin du Luxembourg and the Bois de Boulogne, sitting in cafés and bistros watching the world, rich and poor, go by, and in the evenings he read French and English novels, the classic ones, never the modern. He also saw Helly and her sister Vally, both now working as seamstresses for a Paris fashion house, and he was grateful for their company, not only because he knew no one else in Paris, but because Helly was generous enough to forgive him his past sins. When the weather turned cold Bertha Rauschenbach posted off a winter coat to keep him warm. It wasn’t the only thing she sent him: when he expressed a longing to commission a copy of a Frans Hals painting of a mother and her children, the money was quickly dispatched.

By January Carl was in London, visiting the sights and the museums and taking more English lessons. It must have been his English tutor, recently down from Oxford, who delighted Carl by taking him back to dine at his college high table with the dons in their academic gowns – a fine dinner, as he wrote to Emma, followed by cigars, liqueurs and snuff. The conversation was ‘in the style of the 18th century’ – and men only, ‘because we wanted to talk exclusively at an intellectual level’. In 1903 it was still common for men to be seen as more intellectual than women, and there were no women at high table to disagree. It was Jung’s first brush with the English ‘gentleman’ and he never forgot it, the word often appearing in his letters as a mark of the highest praise.

In Schaffhausen, Emma received a present. It was a painting. In between all his other activities Carl took the time in Paris to travel out into the flat countryside with his easel and paints. He had always loved painting, even as a child, and in future it would go hand in hand with his writing, offering a poetic and spiritual dimension to his words. He found a spot on a far bank of the River Seine, looking across at a hamlet of pitched-roof houses, a church with a high spire, and trees all along. But the real subject of the painting was the clouds, which took up three-quarters of the canvas: light and shining below, dark and dramatic above. The inscription read: ‘Seine landscape with clouds, for my dearest fiancée at Christmas, 1902. Paris, December 1902. Painted by C. G. Jung.’

It might have been a premonition of their marriage.

The painting Carl sent Emma for Christmas 1902.

4

A Rich Marriage (#u0b200f64-3483-5f2b-ab53-508ff0c931b2)

Emma and Carl got married twice: first the civil ceremony on 14 February, with just a few family members in attendance – Carl’s mother and sister, and Emma’s sister Marguerite but not her mother or father – followed by an evening wedding ball at the Hotel Bellevue Neuhausen overlooking the Rhine Falls. Then, two days later, a church wedding in the Steigkirche, the Protestant Reformed Church in Schaffhausen, at which both mothers were present, but not Emma’s father. The bridal couple arrived at the church in the high Rauschenbach carriage used only for weddings, decorated with winter flowers and driven by coachman Braun: Carl in his newly acquired silk top hat and tails, Emma in her white gown, veil and fur cape against the cold – luckily there was no snow that February – waving and smiling at well-wishers left and right. The service was followed by a wedding banquet at Ölberg. Later, on 1 March, there was a further festivity at the Hotel Schiff for the employees of the Rauschenbach factories and foundry.

The wedding banquet was grand, as expected for the eldest daughter of a family of such wealth and high standing: twelve courses, starting with lobster bisque, followed by local river trout, toast and foie gras, a sorbet to precede the main course of pheasant with artichoke hearts accompanied by a variety of salads. The dessert course offered puddings, patisserie, cakes, ice creams and fruit, and each course was accompanied by a selection of wines, ending with a choice of liqueurs, sherry, port or champagne, and finally, coffee, cigars and cigarettes. The bridal couple sat side by side at a long table covered in white damask, decorated with wedding flowers, the family silver, china and glass; the servants of the house in their starched uniforms running to and fro, augmented by extra waiters from the town, each guest assigned their placement. The couple were flanked by their relations and facing the guests: Emma with her veil off her face now, her hair coiled up in the style of the times, Carl in his wedding fraque with a stiff white collar and fancy waistcoat, listening to a long list of toasts and speeches, everything as it should be, at least on the surface.

Except that the father of the bride was not present, a fact which did not escape the guests. Nor, of course, was the father of the groom, Pastor Jung – how to put it – having died some years previously. Then there was the fact that the mother of the groom was extremely large. And the puzzle that Frau Rauschenbach apparently was not present at the civil wedding, only the church wedding two days later. Above all there was the fact that the groom was a penniless doctor, not even a regular one but an Irrenarzt, a doctor of the insane, working in a Zürich lunatic asylum, marrying Emma Rauschenbach, one of the richest and most desirable young women in Switzerland.

Emma’s wedding present to Carl was a gold fob watch and chain from the Rauschenbach factory, a magnificent piece of Swiss craftsmanship engraved around the upper inside rim with the words ‘Fräulein Emma Rauschenbach’ and ‘Dr C. G. Jung’ around the lower, with a charming design of lilies-of-the-valley at the centre, encircling two hands joined in matrimony, the date inscribed on a ribbon below: 16 February 1903. Not the 14th, then, but the 16th. Not the day of the civil wedding but of the church wedding. For Carl the church wedding was of little concern: he had rejected formal religion a long way back, during his battles with his father. ‘The further away from church I was, the better I felt,’ he wrote of his teenage self. ‘All religion bored me to death.’ But to Emma, raised in a conventional haut-bourgeois Swiss family, it was the church wedding that counted.

They spent the days before setting off on their honeymoon on 2 March at Ölberg. Early that morning they were borne away in the green everyday Rauschenbach carriage piled high with labelled trunks and hat boxes, Emma’s mother and sister and the full complement of servants ranged on either side of the grand entrance, waving them off down the hill – ‘Wünsch Glück! Wünsch Glück!’ – past the fountain and the vineyards and on to Schaffhausen railway station and the start of their journey – Emma in her travelling outfit and furs, Carl with his new set of tailored clothes and plenty of books.

After a short visit to Carl’s mother and sister at the Bottminger Mill in Basel they travelled by Continental Express to Paris. The first-class carriages were arranged much like a drawing room, with heavily upholstered seats, writing tables and lamps for reading and curtains at the windows. The restaurant car was elegant, the menus all in French and the food excellent. The night was spent in lavishly adorned salons lits, with hand basin and mirror in the corner and the two bunks made up with fine bedlinen. Stewards in smart uniforms appeared at any time of day or night at the ring of a bell, and there was a quiet deference to all the proceedings. From Paris they travelled by train and boat to London, and thence down to Southampton to board the ocean liner taking them to Madeira, Las Palmas and Tenerife, always staying in the best hotels, then back via Barcelona, Genoa and Milan, arriving back at Schaffhausen on 16 April.

For Carl it was the start of a new life of considerable luxury; for Emma it was the beginning of getting to know the man she had married. He certainly looked the part: tall, handsome, beautifully attired. But at some stage during the honeymoon there was a quarrel about money. Swiss law gave the husband, as head of household, ownership of all his wife’s possessions, and the power to make all final decisions in matters pertaining to family life, including the education of the children. Accordingly, the first thing Carl had done once they were married was to pay off his 3,000-franc debt to the Jung uncles. The amount of the debt tells you something about Carl’s incipient taste for good living, a side of his character Emma was now discovering for herself. ‘Honeymoons are tricky things,’ Jung admitted to a friend years later. ‘I was lucky. My wife was apprehensive – but all went well. We got into an argument about the rights and wrongs of distributing money between husbands and wives. Trust a Swiss bank to break into a honeymoon!’ He laughed at the memory. But Emma had seen Carl’s temper and how it could flare up out of nowhere. Ever since he was a boy Carl had flown into rages. In time Emma learnt that the rages soon passed. But for now it was distressing.

Then there was the question of sex. Was Emma surprised to discover that her husband was still a virgin? Two years earlier his mother had commented, on one of her visits to the Burghölzli and before he became engaged to Emma, that Carl knew too few women. Almost none, in fact. Jung himself later admitted he had not had ‘an adventure before marriage, so to speak’ and until his marriage he was ‘timidly proper with women’. In one way this may have been a relief to Emma, given the terrible fate of her father. But she would not have been the only ‘apprehensive’ one, as Carl suggested. And now she knew Carl was not quite the man of the world he presented on the surface.

Then there was also the evident difference in their personalities. Quiet and studious as a child, as an adult Emma came across as shy and reticent, sometimes hiding behind the formality of her social background. With marriage she happily took her place in the background, giving those who did not know her the impression that she was, if not the Hausfrau, then just the wife. Carl was the extroverted one, the one everyone wanted to talk to. But it was only half the story, as Emma was finding out. The ‘other’ Carl, the hidden one, was unsure, introverted, plagued by a deep sense of social inferiority, and much in need of Emma’s quiet support. Whilst Carl’s childhood had been strange and lonely, Emma’s had been safe, loving and happy, protected from the ills of the world at the Haus zum Rosengarten, overprotected perhaps. That world did not begin to break up until she was twelve, when her father first became ill with syphilis, and by then the confidence bestowed by a happy childhood was deeply embedded. She also had the confidence which came from belonging to the privileged niveau of society. It was a feeling Emma carried with her all her life, allowing her to behave in the quiet, modest manner noted by everyone who met her. A double confidence. Her new husband had neither.

On 24 April, shortly after returning from honeymoon, the Jungs moved into a rented apartment in Zürich, on Zollikerstrasse, the road leading up to the Burghölzli asylum. Here, south of the city, the houses were solid rather than grand, the apartments spacious and the countryside within easy reach for afternoon walks. Unlike the eastern slopes of Zürich, which lay in the shade with damp air and bad soil, the southern slopes were on the sunny side, with good soil and little fog. Carl had taken up Bleuler’s offer of a temporary post at the asylum, acting as his deputy whilst others were on leave, just filling in time whilst he looked for a better job elsewhere. It was a typically generous gesture from Bleuler who had already suffered Carl’s precipitate resignation six months earlier, and it was received with a typically grudging gratitude by Carl.

With Carl back at work, Emma took stock of her married state. She started to set up home, arranging for furniture and fine antique pieces to be brought over by horse and cart from the Ölberg estate. Her mother came to help, plus a live-in maid, also from Schaffhausen, and gradually the apartment took shape. It was not the kind of living Emma was used to but it was only temporary after all. In many ways it was refreshing. From her bedroom window in the mornings she watched as bare-footed farm boys in short trousers and braces led cows down the hill to the slaughterhouse, and smallholders from the neighbouring village of Forch came down in their wooden farm carts to sell their vegetables at the market, the husband in front driving the horse, the wife and children behind among the laden wicker baskets. Given Zollikon’s proximity to the Burghölzli asylum, quite a few of the villagers worked there as helpers, the low wages still better than they could earn as farm labourers or domestic servants.

Carl left for work early every morning, walking up the hill through farmland and meadow, past the Burghölzli kitchen gardens where inmates in overalls were already hoeing and digging, watched over by the Wärters in their long green garden aprons – then on through the gates of the asylum, up the front steps and straight into the early morning meeting. These days he was always smartly dressed in a suit and tie, waistcoat, and his gold fob watch and chain, which he wore till the day he died. But once on the wards he donned the doctor’s white coat like the rest of the medical team and his daily routine began. He rarely got back before eight because Bleuler insisted Burghölzli staff eat their meals with the inmates, and the days were long for Emma left sitting in their apartment with nothing much to do and hardly any friends.

Some days she would make her way into the centre of town, walking down Zollikerstrasse, then taking the tram to Stadelhofen, where she joined a crowded, busy, modern city. Zürich was so much larger, noisier, and more commercial than Schaffhausen. Everything seemed so much faster. Trams could travel at fifteen kilometres an hour, conveying shop girls, hairdressers, waiters, bank clerks and office workers from the outskirts into the business district and back out again after a long ten-hour day. The tram drivers and conductors sported military-style uniforms and handlebar moustaches, as did the captains of the paddle steamers which plied their way across the lake, bearing freight as well as passengers.

By 1903 Zürich was a city on the make. Its population had doubled since 1890 to over 162,000 and was growing by the day. The unification of the outlying districts under one ‘City Administration’ in 1893 had propelled it into an era of thrusting capitalism and commercial activity, quickly followed by a property boom which led to massive land and building speculation, which in turn led to a financial crisis. But by the turn of the century the recovery was in full swing. Everything relied on Zürich’s geographical position on the Limmat and the Sihl rivers flowing from Lake Zürich, their bridges linking the two parts of the town, with a chain of Alps beyond, each peak with a Gasthof or hotel on the summit. Zürich was postcard-pretty and good for business: commerce and finance, banks, a stock exchange, import and export, construction and engineering, heavy and light industry, all thrived on the shores of the lake. Further out in the industrial district of Sihl factories and sweatshops produced silk, cotton, lace and embroidery and bit machinery of every sort, all stored in warehouses on the bank of the Limmat beyond the Bahnhof Brücke, the bridge leading off Bahnhofstrasse. Rich foreigners were beginning to flock to Zürich for the Alps, the air, the shops and the lake. Fashionable hotels catered for this early tourist industry, none grander than the Baur-au-Lac, with gardens leading down to the lake. ‘Hotel-keepers who wish to commend their houses to British and American travellers are reminded of the desirability of providing the bedrooms with large basins, foot baths, plenty of water, and an adequate supply of towels,’ advised the Baedeker guide. Thomas Cook & Son had a bureau in the Hauptbahnhof, the central station, if further guidance were needed; they reminded travellers that no servants were allowed on the platforms: luggage had to be conveyed by the uniformed porters.

As spring gave way to a hot summer and she got used to her new surroundings, Emma found there was plenty to do in Zürich, quite apart from her usual reading, writing, needlework or knitting, and helping Carl to write up his daily reports and research. There were plenty of museums: the Ethnographical Museum, the Municipal Museum of ‘Stuffed Wild Animals’, the Landesmuseum, a massive building in the neo-Gothic style recently opened in celebration of Zürich’s increasing importance, housing an extensive collection of Swiss artefacts from prehistoric to modern times – bridal coffers, carved altars, old sleighs, tapestries, a distillery from the ancient Benedictine monastery of Muri, musical instruments, local Swiss Trachts (each canton having its own costume), china from the old factory at Schoren, banners and ducal hats and military uniforms of every kind, plus an entire Zürich house from the fourteenth century. But as far as Emma was concerned there was nothing more important than the Zürich Central Library with its collection of 160,000 books and its large, high-ceilinged, silent reading room – open in the morning from ten until twelve, and again after lunch from two till six, entry costing 60 rappen – ideal for her research into the Legend of the Holy Grail, which she now returned to with joy, like greeting an old friend.

Emma found a pleasing anonymity in Zürich: whilst the Rauschenbachs were the foremost family of Schaffhausen, known and respected by everyone, here Emma was mostly unknown and unregarded, in spite of her great wealth. The old ruling families of Zürich kept very much to themselves, entertaining one another in their villas in quiet, prosperous districts such as Seefeld, or meeting for private luncheons in fine restaurants, or at one of their many Vereins: the Yacht Club, the Rifle Club, the Rowing Club, the Riding Club, and the recently founded Automobile Club. Who among them would want to pass the time of day with the wife of an Irrenarzt employed at the Burghölzli asylum – an institution which had, after all, been built high up on the Zollikon hill, well away from the town, for a reason? This snobbery bothered neither Emma nor Carl, who were content, each for their own reasons, to be outsiders: Carl because he was born that way, Emma because society never held much importance for her, preferring as she did the company of close friends and family.