По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

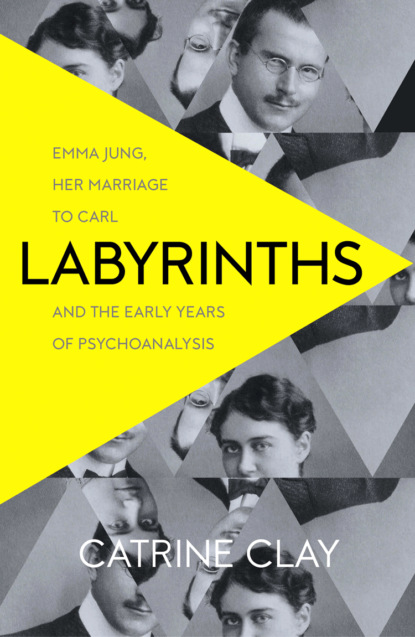

Labyrinths: Emma Jung, Her Marriage to Carl and the Early Years of Psychoanalysis

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Marguerite often came to visit during that first year and the sisters would wander up and down the Bahnhofstrasse or the Parade Platz, though Emma bored of it quickly, one shop being much like the next. With the exception of the fashion houses. Both sisters were interested in the latest fashions, noting they were distinctly more modern in Zürich than sleepy Schaffhausen. Day wear was much the same: long-skirted and high-necked, worn with hats and button boots, but evening gowns were very décolleté, set off by heavy strings of pearls. The waists seemed narrower in Zürich, fishbone corsets pulled tight every morning by the maid, and the hats seemed larger, decorated with plumes and bows and veils, the hair curled with heated irons and pinned up with combs and grips. Feather boas and tassels were the fashion that year, and no lady went about without gloves, short for the day, long for the evenings. In the summer months the dark patterns gave way to white – long white skirts, high-necked white blouses, white stockings, white shoes. Swiss lace and embroidery came into their own then, along with parasols and wide straw hats decorated with ribbons and cherries and artificial flowers. Perfumes of violets, lilies-of-the-valley or eau de cologne were especially popular. On the Bahnhofstrasse in the recently opened Salon de Beauté there were boxes of rice powder, pots of white and rose creams, tiny bottles of nail polish and glass balls of bath salts displayed in discreetly half-netted windows, offering manicures and pedicures and other beauty treatments in the privacy of curtained-off niches, administered by trained young ladies in white overalls with their hair tightly pulled back.

After their shopping exertions Emma and Marguerite usually went to a café for kaffee or thé citron and pâtisserie. Other days they might take the cable tram up to the Grand Hotel Dolder, with its wide terrace and Zeiss telescope to better appreciate the view of the Alps. There were two picture houses showing newsreels and new features like The Great Train Robbery, jerky and silent except for the piano accompaniment, though good bourgeois people rarely visited them other than incognito, via a private side door. Emma and Marguerite preferred to promenade along the many quais which bordered the lake, or sit in the gardens of the Tonhalle – the grand concert hall built in 1895 in imitation of the Trocadero in Paris – listening to one of the military bands and talking about Marguerite’s fiancé, Ernst Homberger, the son of another of their father’s former business associates in Schaffhausen. One thing they did not do was visit the Panoptikum on the seamier side of the Bahnhof Bridge, with curtains drawn and dimly lit by gaslight, where men could, by looking through small panes, view a tiger hunt in the Sudan, or the ‘Rape of the Sabines’, or a wax Sarah Bernhardt in a negligee, or the ‘medical’ exhibition with lifesize models of naked women.

Sunday was Carl’s day off. In the morning all the church bells, Protestant and Catholic, rang out across Zürich and families put on their Sunday best to attend the services, prayer books in hand, little girls with hair done up Heidi-style, boys in matelot suits. Not the Jungs, however. Carl had vowed never to set foot in a church again, other than on unavoidable occasions such as his own wedding, and he was determined not to have any of his children confirmed, remembering the debilitating boredom and depression which overcame him during the instruction given him by his father, who was all the while denying his own religious doubts, battling with his unnamed torments. Emma accepted Carl’s rejection of formal religion without much trouble, not least because by Sunday they were often on the train to Schaffhausen, to be met at the railway station by coachman Braun as usual, then up the hill to Ölberg where Emma’s mother and Marguerite and the servants waited, and Emma was back to the world she knew and loved.

Their first years of married life were happy for them both. A studio portrait taken at that time shows the couple side by side and close, looking into the lens of the camera with confidence and ease. Emma’s wavy brown hair is done simply in a modern style – softly off the face. Her expression is shy but calm and direct, and quite determined. She is wearing a blouse in the Grecian style, high-necked, modern again. The skirt is long, simple and elegant, very unlike the elaborate outfits displayed in most of the fashion magazines. She may be standing on a box – the custom for studio photographs if the difference in height was too great – but she still looks half Carl’s size. He stands there solid, with his hand nonchalantly in his pocket – dark suit, light waistcoat, a stiff-collared white shirt and small bow tie – a confident man of the world with no trace of the pompous and rather unhappy student of earlier photographs. His gold-rimmed spectacles glint in the studio lights and it is just possible to see the gold chain of his wedding present from Emma. His small moustache is trimmed the way it will be for the rest of his life. In another take of the pose, Emma is smiling more, probably encouraged by the photographer, but Carl is just the same. He looks – there is no other way to put it – like the cat that got the cream.

‘I’m sitting here in the Burghölzli and for a month I’ve been playing the part of the Director, Senior Physician and First Assistant,’ Carl wrote on 22 August 1904 to Andreas Vischer, an old friend from university days. It was summer, and everyone else was away on holiday. ‘So almost every day I’m writing twenty letters, giving twenty interviews, running all over the place and getting very annoyed. I have even lost another fourteen pounds in the last year as a result of this change of life, which otherwise is not a bad thing of course. On the contrary, all that would be fine (for what do we want from life more than real work?) if the public uncertainty of existence were not so great.’ He might claim it annoyed him, but his tone is buoyant, optimistic. There was nothing Carl loved more, he admitted, than work – at least work that made sense to him: investigating the dark corners of the mind. Emma was getting used to the idea that she hardly ever saw him.

By the end of the year it was becoming clear that Jung was not going to find another job elsewhere, certainly not in his home town of Basel, which had been his plan. Apparently his falling-out with Professor Wille had well and truly ruined his chances: the job of director at the Basel asylum, which Carl had applied for, was given to one of Wille’s German colleagues, a man named Wolff. Swinging from high spirits to low, Carl called it the ‘Basel calamity’, which had ‘wrecked for ever’ his academic career in Switzerland. Now he had to consider remaining in Zürich and at the Burghölzli. ‘I might as well sit under a millstone as under Wolff,’ he wrote to Vischer, ‘who will stay up there immovably enthroned for thirty years until he is as old as Wille. For no one in Germany is stupid enough to take Wolff seriously, as Kraepelin has appropriately said, he is not even a psychiatrist. I have been robbed of any possibility of advancement in Basel now.’

Carl did not want to stay in Zürich nor take on a permanent post at the Burghölzli. He had no wish to do endless ward rounds, attend endless staff meetings, write up endless daily reports. He wanted to continue his research into the workings of the unconscious. He wanted to bring scientific proof to this new field and write scientific papers about his findings to be published in medical journals like the Journal für Psychologie und Neurologie. He wanted to make his name. But he had been rejected for the post in Basel and now he didn’t know what to do. His crisis confronted Emma with the other Carl again, the one who fell out with colleagues through arrogance and an unshakeable conviction in his superior intelligence, but then became cast down and plagued with doubts when things went wrong. There was no steadiness in Carl, she discovered. And yet to the outside world he appeared his usual loud, confident, charismatic self. It was as though he were two different people.

The one thing which never left him was his vaulting ambition. ‘As usual you have hit the nail on the head with your accusation that my ambition is the agent provocateur of my fits of despair,’ Jung wrote to Freud some years later. He could admit it, but he could do little about it. Because the ambition was not just to gain worldly acclaim; it was in order to understand the complex workings of the unconscious because he suffered so much from it himself.

Bleuler again came to the rescue. He wasn’t a crafty Swiss peasant for nothing and he wanted to keep his exceptional young colleague at the Burghölzli. So he made Jung an offer he couldn’t refuse: he could continue the word association research he had begun with his Burghölzli colleague Franz Riklin, but more systematically, in a laboratory with proper equipment, and, under Bleuler’s own supervision, write papers to be published in the medical journals. These could later be gathered into a book on this important new field of scientific research. Carl accepted. Bleuler and Jung shared an interest in the paranormal as a means of accessing the unconscious, and the Burghölzli already enjoyed an international reputation as great and controversial in its way as Freud had acquired after the publication of The Interpretation of Dreams in 1900. Everyone in the field, it seemed, wanted to research the unconscious, whether through dreams, hypnosis, the paranormal, or word association tests. Jung needed a base from which to launch himself. Bleuler needed the best doctors specialising in diseases of the mind, both for the sake of his patients and the reputation of the Burghölzli. Where else, after all, could Carl find so many guinea pigs to experiment on? Discussing it with Emma, Carl could see there was no better solution.

However, Carl was now tied to doing all the routine work as well – a twelve-hour day at least – and being completely teetotal, and, above all, having to move back and live on site. Nevertheless, by October 1904 Jung had exchanged the part-time for the full-time position, and he and Emma moved into an apartment in the main building of the Burghölzli, on the floor above Bleuler and his wife Hedwig and their children, bringing Emma’s maid and the beautiful furniture with them. The only concession made to Herr and Frau Doktor Jung was that Carl was allowed to miss the midday meal with patients and staff and return to the apartment to have lunch with his wife. So began Emma’s new life as the wife of an Irrenarzt, living amongst hysterics, schizophrenics, catatonics, alcoholics, addicts, chronic neurotics and suicidal depressives – people who had lost their minds for one reason or another, and who spat and screamed and paced the wards, up and down, shouting obscenities, tearing at their hair, breaking the furniture. The contrast with her former life was complete.

Now she had to find a way of relating to the kind of people she had never expected to meet: inmates and staff alike.

It is telling that Emma was able to do it quickly and naturally, as testified by everyone who met her. Of course they knew Herr Doktor Jung had married a wealthy wife, but it was soon noticed that the Frau Doktor did not ‘act wealthy’, dressed simply, and was friendly to everyone equally, regardless of position. She was quite reserved, it was true, but she was liked. For Emma the problem was more the question of how to fill her days. The maid did the cooking and the cleaning, and, unlike Hedwig Bleuler as the wife of the Herr Direktor, she did not have a formal role in the institution. She still helped Carl privately with his research and reports, and she continued to go to the library in Zürich and research the Legend of the Holy Grail, but it still left her with many hours alone. There were just two people nearby who she could visit regularly – a duty or a pleasure, depending on how you looked at it: Carl’s mother and his sister Trudi, because once it became clear that Jung was staying in Zürich he swiftly moved them out of the Bottminger Mill and into an apartment in nearby Zollikon. He did not have much time to see them himself so the visits naturally fell to Emma, the wife and daughter-in-law. It can’t have been easy: most of the time her mother-in-law was normal and good company, but she still heard voices, had visions, and made sudden prophetic announcements. Her second personality always hovered in the background, and you never knew when it might emerge.

Soon Emma found a role to play at the Burghölzli after all, because Eugen Bleuler believed women and wives should be included as much as possible in the daily life of the institution – another of his progressive ideas, quite alien to other lunatic asylums where all women other than the female Wärters were kept well away. Emma was encouraged to join in, participate in social events, and sit at the same tables as the patients as long as there was no danger. There were also regular evening discussion ‘circles’ to which all doctors and their wives were invited. And if a patient was in the rehabilitation phase of their treatment and they were allowed out of the asylum grounds, it was as likely to be Frau Jung or Frau Direktor Bleuler as much as it was one of the Wärters who accompanied them on walks, or even on a short shopping trip. ‘The years at Burghölzli were the years of my apprenticeship,’ Jung acknowledged later. But in a smaller way they were Emma’s too. ‘Dominating my interests and research was the burning question, “What actually takes place inside the mentally ill?”’ Jung wrote. Now, almost by osmosis, it came to interest Emma too.

The other plus for Emma at the Burghölzli was Hedwig, who was a remarkable woman and an early feminist. Eugen Bleuler was already forty-four when he married her in 1901; Hedwig was then a history teacher, twenty-four years old, clever, elegant, charming. They met at one of Bleuler’s lectures at Zürich University, and wed within the year. Hedwig’s ambition had been to become a lecturer herself but it was not possible in Switzerland at that time, it being the preserve of men. And once she was pregnant she could not continue her studies anyway, so her life centred round her role as Frau Direktor Bleuler, and she made very good use of it, supporting her husband in every way she could. Their apartment was large enough to accommodate two maids, had bedrooms enough for their growing family, and a large, sunny room for Bleuler’s schizophrenic sister Pauline. There was a library and a stairway which led directly down to the wards, so Bleuler could be there at any time of day or night if there was a crisis. Hedwig’s special interests were the abstinence movement and women’s position in a modern society. Years later she travelled throughout Switzerland lecturing on both, but whilst the children were growing up she limited herself to helping her husband at the Burghölzli and editing his lectures and published papers. It was a happy marriage but she always regretted having to give up her own career. ‘The woman is always the one who has to make the sacrifices,’ she said. Another clever woman, then, who had to find her intellectual satisfaction through her husband’s work.

Once back full time at the Burghölzli, Jung was soon dominating the place with his energy and booming laugh. He was happy to spend hours with a patient listening to their strange utterances, finding meaning in their madness. While he was liked by many, some of his colleagues found his presence irritating, accusing him of throwing his weight around, doing just what he wanted and not bothering with the dull administrative work. The Wärters, who did all the day-to-day caring and were only allowed home one afternoon a week, claimed the doctors spent more time on their research than on routine ward rounds, especially Herr Doktor Jung. But Bleuler let him get away with it. Auguste Forel, the former director who still liked to wander about the institution, was soon asking: ‘Who’s running this place, Bleuler or Jung?’

The reason was simple: Bleuler did not want to lose Jung. So he allowed Jung and his ‘esteemed colleague Herr Doktor Riklin’ to spend hours pursuing their word association tests in a laboratory at the back of the main building, near both the laundry and the dairy, wafts of steam emanating from the one and the moos of cows from the other. Riklin was the junior partner in the venture but he had worked on word association tests before, in Germany with Gustav Aschaffenburg who followed Dr Wundt, who in turn referred back to the first tests conducted by Galton in England in the 1880s, each contributing to the growing body of evidence about the unconscious. All over Europe doctors in asylums were experimenting on their patients, and Jung’s papers on the word association tests are filled with references to others already embarked on the same track. The difference was that Jung and Riklin’s methodology was far more systematic, more scientific. They published their findings in the Journal für Psychologie und Neurologie, and Bleuler wrote the introduction when the book was published in 1905 as Studies in Word Association.

The method was described as ‘the uttering of the first word which “occurs” to the subject after hearing the stimulus-word’, and suggested that it would help in the diagnoses and classification of dementia praecox, epilepsy, various forms of imbecility, some forms of paranoia, and the diseases grouped under hysteria, neurasthenia and psychasthenia, ‘not to speak of manic depression with its well-known flight of ideas’. Jung and Riklin went about it systematically and scientifically, by using a much larger pool of guinea pigs and by increasing the number of stimulus words from 100 to 400 – nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs and numerals, using the Swiss dialect form when necessary – and timing the reactions with the greatest possible accuracy using the ‘one-fifth-second stop watch’, the very latest model from the Rauschenbach factory in Schaffhausen. The reaction times varied considerably, sometimes taking up to 6 seconds. Galton had found that the average time was 1.3 seconds. Jung with his modern stopwatch found it was 1.8 seconds, women subjects taking slightly longer. To distract the conscious mind a metronome was used. Other researchers used whistles, trumpets or darkened rooms. At times the tests were done when the subject was ‘in a state of obvious fatigue’, and once ‘in a state of morning drowsiness’ (Jung himself). One important innovative decision of Jung’s was to test ‘normal’ as well as ‘abnormal’ people, and the groups were divided into male and female, ‘educated’ and ‘uneducated’. Everything had to be written up, by hand, night after night. Emma was kept busy, and she was happy to do it.

In those early years of psychoanalysis it was common and considered perfectly acceptable to use friends and relatives as well as patients as subjects for scientific research. Jung and Riklin’s first test was on ‘Normal Subjects’: thirty-eight persons in all, nine men and fourteen women of whom were classified as ‘educated’. The rest were mostly male and female Wärters at the Burghölzli, who, Jung declared, were not so much ‘uneducated’ as ‘half-educated’. The tests were often repeated so that in the end they had 12,400 associations and timings on which to base their conclusions. There were statistics and tables and graphs, and a complicated list of different types of reaction, including those which showed evidence of ‘repression’, a term made familiar in the writings of Sigmund Freud. As with Freud, there was often enough of a description of the person to make an enticing story. Thus ‘Uneducated Woman, Subject No. 1: she is of country origin and became an asylum nurse at the age of seventeen, after having brooded at home for over a year over the unhappy ending of a love affair’. This subject would not or could not understand the stimulus words ‘hate, love, remorse, rattle glass, hammer ears . . . because they intimately touched the complex which she was trying to repress’. The term ‘complex’ was coined by Jung and Riklin to denote ‘personal matter . . . with an emotional tone’. It could be spotted by a significantly longer reaction time and the peculiarly forced nature of the reaction.

Then there were clang associations – that is, based upon sound rather than on concepts: simple, thoughtless, sound similarities – and interesting ‘preservation’ ones, first noted by Aschaffenburg, where ‘the current association revealed nothing, but the succeeding one bears an abnormal character’. There was also the egocentric reaction: grandmother/me; dancing/I don’t like; wrong/I was not, and so on. ‘If we ask patients directly as to the cause of their illness we always receive incorrect, or at least imperfect information,’ explains Jung. ‘If we did receive correct information as in other (physical) illnesses, we should have known long ago about the psychogenic nature of hysteria. But it is just the point of hysteria that it represses the real cause, the psychic trauma, forgets it and replaces it by superficial “cover causes”. That is why hysterics ceaselessly tell us that their illness arose from a cold, from over-work, from real organic disorders.’ He compared their method with Freud’s ‘free association’ and reminded the reader that a ‘delicate psychological intuition in the doctor is as much a requisite as [is] technique for a Psycho-Analysis’. If this all sounds familiar now, it was not then, back in 1904.

Emma appears as ‘Subject no. I, aged twenty-two, very intelligent’, in the ‘educated’ category. By way of introduction Jung wrote: ‘No. I is a married woman who placed herself in the readiest way at my disposal for the experiment and gave me every possible information. I report the experiment in as detailed a way as possible so that the reader may receive as complete a picture as possible. The probable mean of the experiment amounts to 1 second.’

The first five word associations were: head/cloth, 1 second; green/grass, 0.8 seconds; water/fall, 1 sec; prick/cut, 0.8 seconds; angel/heart, 0.8 seconds. So far so good, but reaction 5 was deemed striking because ‘the subject cannot explain to herself how she comes to heart . . .’. Emma denied it was the result of any disturbance from without, and could not find any inner one either. Jung concluded it might therefore be some unconscious stimulus, very likely one of Aschaffenburg’s ‘preservation’ reactions, carried over from the previous prick/cut, which caused ‘a certain slight shade of anxiety, and image of blood’.

‘The subject is pregnant,’ Jung noted with scientific detachment, ‘and has now and then feelings of anxious expectancy.’

There followed a sequence of stimulus words which were not especially memorable, except that ‘to cook’ endearingly elicited ‘to learn’, as did ‘to swim’ – because it was her sister Marguerite who was the swimmer, whereas Emma was apparently still learning. Only Carl could know why 28: lamp/green took 1.4 seconds. It followed threaten/fist, and he noted it was clearly another case of ‘preservation’ and that lamp/green denoted her home life (the colour of the lampshades). He does not say which home, Zürich or Schaffhausen, but it was most likely Schaffhausen and the fist her father’s as he became more and more ill and desperate.

Further associations offered little which was significant for the test but tell us something of Emma’s outlook on life: evil/good; pity/have; people/faithful; law/follow; rich/poor; quiet/peaceful; moderate/drink; confidence/me; lover/faithful; change/false; duty/faithful; serpent/false. And then we come, in no particular order, to: family/father and mother/tell and dear/husband. Father is still the head of the family. Her mother is the one to whom she tells almost everything. Her husband, she loves.

Using his intuition, and inevitably his personal knowledge of Subject No. I, Jung focused on a sequence of associations, nos 70–73: blossom/red; hit/prick; box/bed; bright/brighter. The first pair only took 0.6 seconds. ‘She explains this short reaction by saying that the first syllable of the stimulus-word Blo-ssom brought up the presentation of blood. Here we have a kind of assimilation of the stimulus-word to the highly accentuated pregnancy complex . . . It will be remembered that in the association Prick/Cut (no 4) the pregnancy complex was first encountered,’ yet:

Box/Bed which followed Hit/Prick went quite smoothly without any tinge of emotion. But the reaction is curious. This subject has now and then paid a visit to our asylum and was alluding to the deep beds used there, the so-called ‘box-beds’. But the explanation rather surprised her, for the term ‘box-bed’ was not very familiar to her. This rather peculiar association was followed by a clang-association (Bright/Brighter) with a relatively long time . . . The supposition that the clang-reaction is connected with the previous curious reaction does not, therefore, seem quite baseless . . . assuming a clang-alteration at the suppressed pregnancy complex, the complex becomes very sensible.

By Association 83 we come to injure/avoid. The German for ‘injure’ is schaden. As Jung explains, the word is very like and easily confused with scheiden – divorce. Luckily, apart from these, there were plenty of happy associations too.

So the main complex which emerged from the test was Emma’s fear of the pain of childbirth. Association 43, despise/mépriser, reminds us how well Emma spoke French, but this, it turns out, was not the point. The reaction took 1.8 seconds. Why so, Jung wondered? ‘Despise is accompanied by an unpleasant emotional tone. Immediately after the reaction it came to her that she had had a passing fear that her pregnancy might in different ways decrease her attractiveness in the eyes of her husband. She immediately afterwards thought of a married couple who were at first happy and then separated – the married couple in Zola’s novel Vérité [Truth]. Hence the French form of the reaction.’ Poor Emma.

In his summing up of ‘Subject No. I’, Jung commented:

In reality our experiment shows beautifully, the conscious self is merely the marionette dancing on the stage to a hidden automatic impulse . . . In our subject we find a series of intimate secrets given away by the associations . . . We find her strongest actual complex to be bound up with thoughts about her pregnancy, her rather anxious expectancy, and love of her husband with jealous fears. This is a complex of an erotic kind which has just become acute; that is why it is so much to the front. No less than 18% of the associations can certainly be referred to it. In addition there are a few complexes of considerably less intensity: loss of her former position, a few deficiencies which she regards as unpleasant (singing, swimming, cooking) and finally an erotic complex which occurred many years back in her youth and which only shows itself in one association (out of regard for the subject of the experiment I must, unfortunately, omit a report on this).

Jung ended the German text of Studies in Word-Association giving ‘special thanks to Frau Emma Jung for her active assistance with the repeated revision of the voluminous material’.

5

Tricky Times (#u0b200f64-3483-5f2b-ab53-508ff0c931b2)

Agathe Regina was born at Emma’s family home in Schaffhausen on 26 December 1904, a Christmas child. Emma was twenty-two, had been married for a year and ten months, and now she was a mother. Overnight, it seemed, her life had changed again, this time for ever.

It was common for mothers of Emma’s social class to use a wet nurse to still their babies. But Emma breastfed hers herself. She did not want to hand her baby over to a stranger and deprive herself and the child of this pleasure, as Carl later described it to Freud. Nevertheless, a first baby is a strange and unknown experience. Emma had plenty of help with ‘Agathli’ – little Agathe – whilst she was still at Ölberg with her mother and sister Marguerite, but when she moved back to Zürich and the Burghölzli, keen not to be away from her husband for too long, she largely looked after the baby herself. Feeding took many hours. Waking through the night disturbed sleep. Changing the thick towelling nappies was onerous, though it was the maid’s job to soak them in a pail before washing them by hand, then through the wringer, then hanging them out on a wooden horse by the tiled stove to dry. It was a winter with deep snow, white pitched roofs with icicles hanging from the eves and the window sills, and no hope of using the washing line in the garden. There were coughs and colds and nappy rashes to deal with, and the terrible responsibility of a new life. For a young mother who had shown such anxiety about the pain of giving birth and the fear that having a baby might affect the feelings her husband had for her, Emma was having to grow up very fast indeed.

In addition, Emma had just started what she had longed to do since leaving school: furthering her education. Though it was done circuitously, by helping her husband with his work, it was certainly an education. And she was still going down to Zürich Central Library to pursue her own research into the Grail legend. But now Carl and Emma slipped back into more conventional roles: she as wife and mother; he as husband, breadwinner and authoritative head of house. Carl did not subscribe to ‘Das Weib sei dem Mann untertan’, ‘The woman shall be subservient to the man’, as a popular book, The Way to the Altar, quoting the Bible, reminded, but once Agathe was born things changed in the Jung household. Carl was conventional when it came to parenthood: he saw children largely as the responsibility of the mother. Now his sister Trudi came to help with the secretarial work and Emma found herself more and more on the sidelines. If she hoped it was merely temporary until she found her feet, it didn’t work out that way: within six months she was pregnant again. Anna Margaretha, known as Gretli, and later Gret, was born on 8 February 1906.

Emma’s story was typical enough of the times. Many women were frightened of getting pregnant, either because they already had too large a family or because they were not married, which was worse. There was no safe method of birth control, and a reliance on coitus interruptus had limited success. In 1909 Richard Richter, a German doctor, would develop an early form of an interuterine device using the gut of the silkworm, but it was not marketed until the 1920s, by which time Marie Stopes had opened the first birth control clinic in England, and there were similar initiatives in America and France and Germany. The Catholic Church, however, forbade any form of contraception and the Protestant Church did not look on it with favour either, believing that it was the duty of Christian marriage to ‘increase and multiply and fill the earth’. It all came too late for Emma and Carl anyway.

Sigmund Freud could have told them. His letters to his doctor friend Wilhelm Fliess are full of pleas that he come up with a reliable form of contraception. Every month he and Martha worried she might be pregnant again. Fliess looked into the ‘rhythm method’, making calculations and trying to work out a safe period during Martha’s monthly cycle; he even tried to come up with a similar cycle for Freud himself. Evidently it was not successful: Martha became pregnant six times in ten years. For the first three months of her sixth pregnancy she insisted it was the start of the menopause, not another pregnancy. She couldn’t face it. She had never wanted more than four children. Once the baby, Anna, was born, Martha went to her mother’s in Wandsbek for several weeks of recuperation and there developed ‘a writing paralysis’: she found she literally could not form the words to write Sigmund a letter. Her face was puffy and her teeth hurt. She was only thirty-four and she was exhausted. After that they stopped having sex, that side of their marriage becoming ‘amortised’, as Freud later confided to Emma.

In March 1905 Emma Jung’s father Jean Rauschenbach died. Marguerite and Ernst Homberger, who had married a year earlier, now moved in with Bertha whilst they built a house of their own. Ernst took over the running of the Rauschenbach business from Bertha and Jean’s sister, though the two women had managed it all splendidly during the last years of Jean Rauschenbach’s decline. But custom had it that if there was a man in the family there was no need for the women to carry on working. Ernst, a quiet, ambitious, tough man twenty years his wife’s senior, ran the business for the rest of his working life.

The immediate reaction to Herr Rauschenbach’s death was relief as well as sorrow, his last years being so terrible, shut away from the world. ‘A poor rich man finally closed his eyes last night, but their light had already gone out a long time ago,’ stated the obituary in the Schaffhausen Tagesblatt

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: