По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

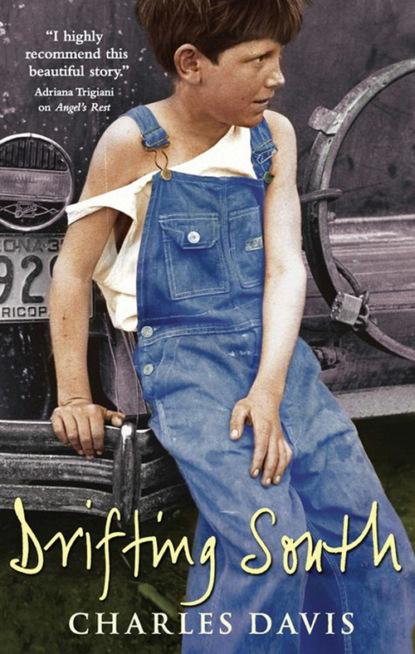

Drifting South

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Drifting South

Charles Davis

Shady is the town where I grew up in every way a young man could, where I saw every kind of good and bad there is to see.Everybody found their true nature in Shady. In a single day, Benjamin Purdue lost his family, his love, his freedom and even his name for reasons he’s never known. Now Ben, the boy he used to be, is dead. And Henry Cole, the man he’s become, is no one he would ever want to know.With only a few dollars in his pocket, Henry journeys back to the dangerous town where it all began. The only place he’s ever called home. As he drifts southward, he gets closer to the beautiful woman whose visit to Shady all those years ago ended in a killing. A woman who holds the keys to his past…and his future.

Charles Davis is a former law enforcement officer and US Army soldier. In 1999 he moved from the coast of Maine to North Carolina, rented a beach house, got a part-time job as a construction worker, and began writing his first novel. The author currently lives in New Hampshire with his wife, son and dog, where he is working on his next novel. Find out more about Charles at www.mirabooks.co.uk/charlesdavis

Drifting South

CHARLES DAVIS

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Prologue

I came to know that lost place the way only a select few did. I was born there, a month too early on the scrubbed pine floor of a whorehouse in the spring of 1942. Ma’s first sight of me was by lantern light. She said I glowed like sunrise and I was the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen. Conceivings could naturally be expected on any given moment in Shady, but few birthings. Ma told me I came sudden and ready to meet the world on a Sunday at midnight and I wasn’t about to be born in a bed where business was conducted. Especially on a Sunday.

“Bad luck,” she said.

Ma was a charm-carrying believer in astrology, signs, luck, and evilness of all shapes and varieties. She believed in goodness, too, and a life after this one that was full of that goodness. And she also believed in a thing that she could feel more than she could see, that she called “the mystic.” It’s right there living alongside us. And sometimes among us, she said. Ma always did have a superstitious nature and peculiar beliefs about so many things compared to most. She was pretty and graceful with curly black hair, and she was a whore and had to be a hardworking one because she believed in keeping her children fed.

We all had fathers of course, but we never were sure who they were as Ma never got much help raising us. I didn’t think she knew who our fathers were, either, by the way she kept trying to hang each of us around the neck of about every man who’d blow through Shady Hollow. They’d always leave for good or try to once they got wind of what her intentions were.

People who lived and worked in Shady Hollow just called it Shady. Wasn’t but twelve dozen of us or so at any one time who had a bed to sleep on that wasn’t being paid by the night for. Most of the faces in Shady changed quicker than day and night coming through the same window. But some took root for years and years for their own good reasons, which weren’t nobody’s business, Ma said. And she told me it was none of my business why we lived there, either, or why she did what she did for a living, when I asked her one time. Ma was only sixteen years older than I was, but she always seemed a lot older no matter what age I was at, even though she didn’t look it.

Shady Hollow lacked a lot of things, like electricity and flushing toilets and a post office, but a person who had nothing in the world but a stretched-out hand never got too cold or too hungry.

Shady never became a real town and the name never was on any map. If you did hear about Shady Hollow in some rambling story from a man or woman you wouldn’t be apt to believe anyway, you’d think the place never did exist. But it did. It was the realest place I’ve ever lived and, even after all of those years I spent in prison, that’s saying something.

Ain’t many places more real than a prison.

From the stories I heard over and over as a boy, Shady Hollow got started in a two-story barn in 1861 by a man named Luke Ebbetts. He named his place “The Establishment on the Big Walker,” and he sold homemade whiskey and hired a whore from Tennessee who soon had more work than she could handle shaking the rafters in the loft.

Luke believed he could make a sizable profit providing to soldiers what the Blue and Gray armies wouldn’t provide for them. Things like liquor and good cigars and women and a hot bath and photographs of them standing tall and fierce in their brushed uniforms and decent hot food and music everywhere. You could hear music in Shady day or night from the earliest times, they say. Night it was louder.

I’m not sure if Mr. Ebbetts would put the things I listed in the same order that I did per a man’s necessity, but he made sure all was aplenty and more to suit any man’s tastes and size of pocketbook.

Luke was a rebel through and through, but he was a businessman above all and he welcomed any uniform wandering into Shady as long as those boys didn’t ask for credit and stacked their weapons when they showed up with their powder dry and ready. Those long rifles would be stacked quick or there’d be shotguns pointed at them. The soldiers who risked coming to Shady Hollow weren’t shy of a fight for certain, but they’d do what Luke said, because the one thing they didn’t come for was to hurl lead at one another. They’d had enough of that, and that’s why they’d walk away from their guns peaceable for a day or two and sometimes even have a drink with their enemy before they’d go to killing each other again on some battlefield up on the Shenandoah.

It wasn’t long before a couple of men who worked for Luke saw how he was making more Confederate and U.S. money than he could bury in canning jars. With his permission, they soon built their own leaning shacks with hand-painted signs atop them, sold whatever things were needed to keep the place running, and hired their own whores who kept more tin roofs shaking. Luke got his cut from all of it.

Before the end of the war, flatboat drivers were braving boulders and swirl holes to float pianos and piano players into Shady, and the rest is pretty much what it came to be—a haphazard outlaw settlement tucked deep into the Blue Ridge Mountains of Southwest Virginia.

Deep. Deep in those mountains.

All sorts came to Shady Hollow once word of the place started drifting out of those foggy hills. Coal miners. Timber workers. Rich northern college kids with old money rearing to depart their new pockets. Gamblers. Orchard pickers. Foreigners. Roamers. Murderers. Thieves. Forgivers. Saviors. And the unrepentant, those rarest of few who in their final dying act would find the will to hold up a shaking middle finger for whoever could see it, and take note of it, one last time.

And politicians and railroaders and mill workers and carpetbaggers and just generally people looking for a good time or those who’d lost their religion or way in some other life.

Fugitives and fortune seekers all of them were, winners and losers, adventuresome folks who’d heard about it and some who came from thousands of miles away. The strangest and the bravest and the most curious of the needy or greedy or forgotten or unwanted seemed to collect there. Good and bad they were, most often a troubled mix of the two things churning away in the same person.

And women were among them. Shady was full of women. Most didn’t stay long like Ma, but they were always coming in and out. They were all sizes and shapes, showing up barefoot and hungry most of the time, a few with a dirty baby nursing on a tit and a screaming little walker in hand.

But some gals made up all fancy would come to us riding tall on a hungry horse or, later, sitting in a new shiny automobile running out of gas with a smile on their face that anybody from Shady could see right through. They had life growing in their bellies, and like everybody else, I reckon they all hoped what they needed to find was there. And one thing for sure, everybody found their true nature in Shady Hollow, because it was the sort of place where a person’s true nature was bound to run into them right quick.

Anyway, Shady wouldn’t have been what it was without its women—it would have been one mean miserable place for sure then—and I reckon the place probably needed children, too. It’s where I grew up.

During my time there, the churchgoers scattered around that part of the Allegheny wilderness country called Shady Hollow “No Business,” because they said no man nor beast had no business going near there. The faithful would proclaim in their town meetings that the government should destroy Shady because there was evilness just a day’s walk from their back pasture fences. The Shady elders would send spies to their gatherings, and we’d soon get secondhand tellings of all the goings-on.

There’d be family men standing up, quoting the Holy Bible in the strongest voices they could muster after their church visits, all of them worn down from trying to save our souls.

But as I’d come to learn already, what some people would say or pray in church on a Sunday morning, and actually do in Shady Hollow on a Saturday night, were two different things.

And you could put a fair wager on that about every time, if you could find somebody foolish enough to take such a bet. Which weren’t likely.

In those church meetings, some of the folks with the loudest voices would come back alone when they could get away with it unnoticed, and they wouldn’t be thumping on a Bible. We figured they had butter and egg money in their pockets, and God sound asleep on one shoulder and the devil picking a five-string banjo on the other. And they’d come back again and again.

We’d welcome them with their stern or bending ways as it suited them, politics and people and religion being the way they are and always have been. So we were a tolerable lot in Shady, even with the Bible toters.

My whole world my first seventeen years, save one trip not so far by miles but a long distance by all other measures, was that curved riverbank with shacks and stick buildings lining both sides of a one-lane road that was mostly mud, tire tracks, horseshit and changing footprints.

Besides the occasional car coming in or out, people rode horses and mules and walked and even peddled bicycles through the mountain country to get there, because the law was so bad about stopping anybody coming in or out on the only dirt road that led to Shady. And some of those yahoos were lazier at thieving than we were by the way they’d hold up folks leaving and charge them for this or that crime, before telling them that if they paid their fine in cash on the spot, they’d be let go and there wouldn’t be a jailhouse stay or court hearing at the county seat of Winslow.

And the fine was always however much money the law could find on them. They’d take watches and rings, even wedding bands for payment, too. When they started taking vehicles and sending people walking out of those freezing hills in the deadness of a January night, something had to be done.

A couple of those lawmen never left the outskirts of Shady Hollow once it came to light what they’d been doing. They were running off business, Ma said, and they were giving Shady the crookedest name of the very crookedest kind.

Those deputy sheriffs never even made it into the hard but forgiving dirt of Polly Hill, neither, once they ignored threats and turned down bribes and were sentenced according to a final judgment by the Shady elders. They ended up bobbing down the river with their bellies bloated and their badges pinned to their foreheads for all to take warning of downstream.

I guess Shady is where I grew up in about every way a young man could and I saw almost every kind of good and bad there is to see. Almost.

Shady Hollow is all gone now, all of it, except for the dead still buried there. I still ain’t sure if the kneelers finally got their prayers tended to or it finally outlived its times. Maybe it just came down to plain bad luck that outsiders might call prosperity.

Over the years many more than a few died trying to find and get to Shady, wandering up on the wrong liquor still or copperhead at the wrong time, or just getting lost in the wilderness. If for no other reason, I still figure there must have been something decent—and maybe even special about the place—if so many folks died trying to find it. It was something in its day, and I’m sure in the last moment before it took its final breath, the diehards of the holdouts threw the party of all parties.

I missed that fine celebration that I can only imagine. But contrary to what some people still claim, it wasn’t because I had six feet of clay piled over top me on Polly Hill.

Most days I’m still pretty sure I ain’t dead yet. Maybe a little bit dead, maybe a whole lot more than a little bit.

But I’m still here.

I had to leave Shady in a great big hurry on September 28, 1959. September 28 fell on a cool early fall Sunday, and I was seventeen years old. And even though I’ve survived so many things since, I still think about it. Especially when dark falls and all gets still and quiet but the visions and ghosts of once was, and once that was never to be, who come back again and again to pay me a visit.

Almost half a century has passed since the shooting. But the sounds and sights of Ma’s yelling and crying, and Amanda Lynn’s screaming, and every single thing that happened on that Sunday afternoon is carved as deep into me as it is into homemade river-rock tombstones overlooking what once was a place called Shady Hollow.

Chapter 1

Harrisburg Federal Penitentiary June 16, 1980

“You’re not out yet, Henry. Well, keep that in mind, yep,” he said.

Charles Davis

Shady is the town where I grew up in every way a young man could, where I saw every kind of good and bad there is to see.Everybody found their true nature in Shady. In a single day, Benjamin Purdue lost his family, his love, his freedom and even his name for reasons he’s never known. Now Ben, the boy he used to be, is dead. And Henry Cole, the man he’s become, is no one he would ever want to know.With only a few dollars in his pocket, Henry journeys back to the dangerous town where it all began. The only place he’s ever called home. As he drifts southward, he gets closer to the beautiful woman whose visit to Shady all those years ago ended in a killing. A woman who holds the keys to his past…and his future.

Charles Davis is a former law enforcement officer and US Army soldier. In 1999 he moved from the coast of Maine to North Carolina, rented a beach house, got a part-time job as a construction worker, and began writing his first novel. The author currently lives in New Hampshire with his wife, son and dog, where he is working on his next novel. Find out more about Charles at www.mirabooks.co.uk/charlesdavis

Drifting South

CHARLES DAVIS

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Prologue

I came to know that lost place the way only a select few did. I was born there, a month too early on the scrubbed pine floor of a whorehouse in the spring of 1942. Ma’s first sight of me was by lantern light. She said I glowed like sunrise and I was the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen. Conceivings could naturally be expected on any given moment in Shady, but few birthings. Ma told me I came sudden and ready to meet the world on a Sunday at midnight and I wasn’t about to be born in a bed where business was conducted. Especially on a Sunday.

“Bad luck,” she said.

Ma was a charm-carrying believer in astrology, signs, luck, and evilness of all shapes and varieties. She believed in goodness, too, and a life after this one that was full of that goodness. And she also believed in a thing that she could feel more than she could see, that she called “the mystic.” It’s right there living alongside us. And sometimes among us, she said. Ma always did have a superstitious nature and peculiar beliefs about so many things compared to most. She was pretty and graceful with curly black hair, and she was a whore and had to be a hardworking one because she believed in keeping her children fed.

We all had fathers of course, but we never were sure who they were as Ma never got much help raising us. I didn’t think she knew who our fathers were, either, by the way she kept trying to hang each of us around the neck of about every man who’d blow through Shady Hollow. They’d always leave for good or try to once they got wind of what her intentions were.

People who lived and worked in Shady Hollow just called it Shady. Wasn’t but twelve dozen of us or so at any one time who had a bed to sleep on that wasn’t being paid by the night for. Most of the faces in Shady changed quicker than day and night coming through the same window. But some took root for years and years for their own good reasons, which weren’t nobody’s business, Ma said. And she told me it was none of my business why we lived there, either, or why she did what she did for a living, when I asked her one time. Ma was only sixteen years older than I was, but she always seemed a lot older no matter what age I was at, even though she didn’t look it.

Shady Hollow lacked a lot of things, like electricity and flushing toilets and a post office, but a person who had nothing in the world but a stretched-out hand never got too cold or too hungry.

Shady never became a real town and the name never was on any map. If you did hear about Shady Hollow in some rambling story from a man or woman you wouldn’t be apt to believe anyway, you’d think the place never did exist. But it did. It was the realest place I’ve ever lived and, even after all of those years I spent in prison, that’s saying something.

Ain’t many places more real than a prison.

From the stories I heard over and over as a boy, Shady Hollow got started in a two-story barn in 1861 by a man named Luke Ebbetts. He named his place “The Establishment on the Big Walker,” and he sold homemade whiskey and hired a whore from Tennessee who soon had more work than she could handle shaking the rafters in the loft.

Luke believed he could make a sizable profit providing to soldiers what the Blue and Gray armies wouldn’t provide for them. Things like liquor and good cigars and women and a hot bath and photographs of them standing tall and fierce in their brushed uniforms and decent hot food and music everywhere. You could hear music in Shady day or night from the earliest times, they say. Night it was louder.

I’m not sure if Mr. Ebbetts would put the things I listed in the same order that I did per a man’s necessity, but he made sure all was aplenty and more to suit any man’s tastes and size of pocketbook.

Luke was a rebel through and through, but he was a businessman above all and he welcomed any uniform wandering into Shady as long as those boys didn’t ask for credit and stacked their weapons when they showed up with their powder dry and ready. Those long rifles would be stacked quick or there’d be shotguns pointed at them. The soldiers who risked coming to Shady Hollow weren’t shy of a fight for certain, but they’d do what Luke said, because the one thing they didn’t come for was to hurl lead at one another. They’d had enough of that, and that’s why they’d walk away from their guns peaceable for a day or two and sometimes even have a drink with their enemy before they’d go to killing each other again on some battlefield up on the Shenandoah.

It wasn’t long before a couple of men who worked for Luke saw how he was making more Confederate and U.S. money than he could bury in canning jars. With his permission, they soon built their own leaning shacks with hand-painted signs atop them, sold whatever things were needed to keep the place running, and hired their own whores who kept more tin roofs shaking. Luke got his cut from all of it.

Before the end of the war, flatboat drivers were braving boulders and swirl holes to float pianos and piano players into Shady, and the rest is pretty much what it came to be—a haphazard outlaw settlement tucked deep into the Blue Ridge Mountains of Southwest Virginia.

Deep. Deep in those mountains.

All sorts came to Shady Hollow once word of the place started drifting out of those foggy hills. Coal miners. Timber workers. Rich northern college kids with old money rearing to depart their new pockets. Gamblers. Orchard pickers. Foreigners. Roamers. Murderers. Thieves. Forgivers. Saviors. And the unrepentant, those rarest of few who in their final dying act would find the will to hold up a shaking middle finger for whoever could see it, and take note of it, one last time.

And politicians and railroaders and mill workers and carpetbaggers and just generally people looking for a good time or those who’d lost their religion or way in some other life.

Fugitives and fortune seekers all of them were, winners and losers, adventuresome folks who’d heard about it and some who came from thousands of miles away. The strangest and the bravest and the most curious of the needy or greedy or forgotten or unwanted seemed to collect there. Good and bad they were, most often a troubled mix of the two things churning away in the same person.

And women were among them. Shady was full of women. Most didn’t stay long like Ma, but they were always coming in and out. They were all sizes and shapes, showing up barefoot and hungry most of the time, a few with a dirty baby nursing on a tit and a screaming little walker in hand.

But some gals made up all fancy would come to us riding tall on a hungry horse or, later, sitting in a new shiny automobile running out of gas with a smile on their face that anybody from Shady could see right through. They had life growing in their bellies, and like everybody else, I reckon they all hoped what they needed to find was there. And one thing for sure, everybody found their true nature in Shady Hollow, because it was the sort of place where a person’s true nature was bound to run into them right quick.

Anyway, Shady wouldn’t have been what it was without its women—it would have been one mean miserable place for sure then—and I reckon the place probably needed children, too. It’s where I grew up.

During my time there, the churchgoers scattered around that part of the Allegheny wilderness country called Shady Hollow “No Business,” because they said no man nor beast had no business going near there. The faithful would proclaim in their town meetings that the government should destroy Shady because there was evilness just a day’s walk from their back pasture fences. The Shady elders would send spies to their gatherings, and we’d soon get secondhand tellings of all the goings-on.

There’d be family men standing up, quoting the Holy Bible in the strongest voices they could muster after their church visits, all of them worn down from trying to save our souls.

But as I’d come to learn already, what some people would say or pray in church on a Sunday morning, and actually do in Shady Hollow on a Saturday night, were two different things.

And you could put a fair wager on that about every time, if you could find somebody foolish enough to take such a bet. Which weren’t likely.

In those church meetings, some of the folks with the loudest voices would come back alone when they could get away with it unnoticed, and they wouldn’t be thumping on a Bible. We figured they had butter and egg money in their pockets, and God sound asleep on one shoulder and the devil picking a five-string banjo on the other. And they’d come back again and again.

We’d welcome them with their stern or bending ways as it suited them, politics and people and religion being the way they are and always have been. So we were a tolerable lot in Shady, even with the Bible toters.

My whole world my first seventeen years, save one trip not so far by miles but a long distance by all other measures, was that curved riverbank with shacks and stick buildings lining both sides of a one-lane road that was mostly mud, tire tracks, horseshit and changing footprints.

Besides the occasional car coming in or out, people rode horses and mules and walked and even peddled bicycles through the mountain country to get there, because the law was so bad about stopping anybody coming in or out on the only dirt road that led to Shady. And some of those yahoos were lazier at thieving than we were by the way they’d hold up folks leaving and charge them for this or that crime, before telling them that if they paid their fine in cash on the spot, they’d be let go and there wouldn’t be a jailhouse stay or court hearing at the county seat of Winslow.

And the fine was always however much money the law could find on them. They’d take watches and rings, even wedding bands for payment, too. When they started taking vehicles and sending people walking out of those freezing hills in the deadness of a January night, something had to be done.

A couple of those lawmen never left the outskirts of Shady Hollow once it came to light what they’d been doing. They were running off business, Ma said, and they were giving Shady the crookedest name of the very crookedest kind.

Those deputy sheriffs never even made it into the hard but forgiving dirt of Polly Hill, neither, once they ignored threats and turned down bribes and were sentenced according to a final judgment by the Shady elders. They ended up bobbing down the river with their bellies bloated and their badges pinned to their foreheads for all to take warning of downstream.

I guess Shady is where I grew up in about every way a young man could and I saw almost every kind of good and bad there is to see. Almost.

Shady Hollow is all gone now, all of it, except for the dead still buried there. I still ain’t sure if the kneelers finally got their prayers tended to or it finally outlived its times. Maybe it just came down to plain bad luck that outsiders might call prosperity.

Over the years many more than a few died trying to find and get to Shady, wandering up on the wrong liquor still or copperhead at the wrong time, or just getting lost in the wilderness. If for no other reason, I still figure there must have been something decent—and maybe even special about the place—if so many folks died trying to find it. It was something in its day, and I’m sure in the last moment before it took its final breath, the diehards of the holdouts threw the party of all parties.

I missed that fine celebration that I can only imagine. But contrary to what some people still claim, it wasn’t because I had six feet of clay piled over top me on Polly Hill.

Most days I’m still pretty sure I ain’t dead yet. Maybe a little bit dead, maybe a whole lot more than a little bit.

But I’m still here.

I had to leave Shady in a great big hurry on September 28, 1959. September 28 fell on a cool early fall Sunday, and I was seventeen years old. And even though I’ve survived so many things since, I still think about it. Especially when dark falls and all gets still and quiet but the visions and ghosts of once was, and once that was never to be, who come back again and again to pay me a visit.

Almost half a century has passed since the shooting. But the sounds and sights of Ma’s yelling and crying, and Amanda Lynn’s screaming, and every single thing that happened on that Sunday afternoon is carved as deep into me as it is into homemade river-rock tombstones overlooking what once was a place called Shady Hollow.

Chapter 1

Harrisburg Federal Penitentiary June 16, 1980

“You’re not out yet, Henry. Well, keep that in mind, yep,” he said.