По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

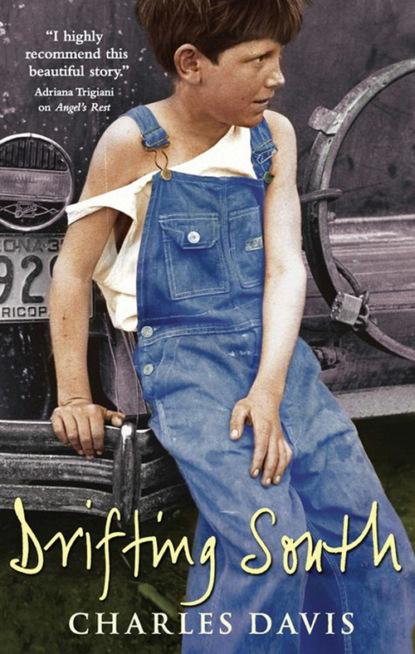

Drifting South

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I even remembered his name. It was Mr. Charles. I didn’t know if Charles was his first name or last name, but that’s what Aunt Kate called him.

“Empty your hands!” Uncle Ray yelled at him.

I raised one of my hands to try to say something to stop whatever was about to happen from happening, and tell Uncle Ray everything was all right and to simmer down whatever it was that was boiling up in him.

“Drop that gun, Ray!” the Shady elder ordered.

Uncle Ray paid no attention to Elder Butch Sarver but kept his gun leveled on Mr. Charles. The odd thing was, Charles didn’t even act like he’d heard a thing or knew a gun was pointed at him.

I was turning to Amanda Lynn to see if she could figure out what was going on and do something to settle everybody down. I figured her and Mr. Charles had traveled up together. But out of the corner of my eye, I saw him walking toward me now even faster, so I turned back and in one quick motion, he raised the front of the newspaper he was toting a couple of inches, and two explosions came out of that paper so loud it sounded like cannons had shot from it, and the paper caught on fire.

Uncle Ray flew backward toward me and Amanda Lynn, and Ma screamed.

Charles dropped the newspaper and started leveling a silver pistol in my direction and I froze still like I was dead already. I was sure I was, looking down the barrel of that big gun. Then a shot came from behind him.

He turned and fired three quick shots and one of the elders, Butch Sarver, fell forward, dropping one of his guns. Butch tried to raise his other revolver from where he was lying and the man with the ice-water eyes, who I’d known the year before but only a little more than I could claim knowing a complete stranger, took a careful long aim with both hands and shot him again.

Butch’s face, or what was left of it, dropped into a mud hole and didn’t come back up.

When Charles turned back to kill me, I’d picked up Uncle Ray’s gun and I was already squeezing the trigger slow and steady, just like he’d taught me as I kept the front sight in the middle of Mr. Charles’s chest.

Chapter 5

It was early morning now, and as orange colors started taking over the sky and the bus made its way through the bottom end of the Shenandoah Valley, I kept wondering again like I’d had a thousand times if Uncle Ray was following his own nature that terrible evening.

Uncle Ray had always told me that the time would probably come when I might need to fight for my life or run for my life, and I’d have to choose quick and wise or I might never leave those mountains whether I wanted to or not. That was the sort of thing that made me think of the choice he made that day so long ago. I remembered how he told me once that I wasn’t born with two feet to just stand on and get killed.

And he told me that cowardice was a much misunderstood thing by most—those of the weaker stock. The same bunch who may talk loud around like weak ears, but stand to the side and become quiet men and steer clear of actual situations where they may have to come face-to-face with such a thing.

As the bus headed south toward Roanoke and then Shawsville, I couldn’t think of a single lesson of Uncle Ray’s that didn’t come in handy at some time or another. Looking around at the children keeping their mommas awake and having a time of things on that bus at such an early hour, I wondered if most boys from other places got lessons on fighting and running so young, and do so much of it, like boys in Shady Hollow did. I reckoned they probably didn’t.

When the bus neared Christiansburg and started having a hard time going up those rugged old mountains, I felt like I was home already and I wished I had a window that would roll down so I could smell it. It’s hard to describe such a feeling that I had that early June morning as the sun was just starting to blaze up the hills and ridges. It was one of those full, peaceful feelings that comes so seldom and sits way deep down inside a person. It made me hopeful, like there was more going on than just another day had come. I wondered if maybe my long spell of bad luck had finally come to an end.

My anger wasn’t gone from me, I knew that, but it was being stilled the closer I got to home. I’d never figured that would happen, but I was starting to feel good and young again in ways you only get when it comes natural like it was doing.

I knew I couldn’t ever get back the years I’d lost and that fact still set in a fiery bad place in me like it always had, but now it looked to me that maybe some answers and a sunny day or two were ahead of me. I didn’t feel like I was just taking a breath to take another one maybe, to only then be able to take another one. It felt real good inside is what I’m saying, and that was a new thing for me. I didn’t feel so dead inside anymore. I felt alive in all ways, many of them I’d forgotten that I even could or ever had felt before. My stop was coming up soon, and I’d never been so dang anxious about anything.

I kept wondering what I’d say after being gone for so long, if Ma still had my old fiddle and other things I’d known as a boy, what I’d holler walking into Hoke’s, and especially, all of the things I needed to say and ask Ma and my brothers when I first saw them after we’d had a chance to fellowship and get to know one another again, if I could do that without facing the most serious of things with them first. Truth was I didn’t know what I’d do or how I’d act when I stepped foot there. As loud as the things were inside me, the years had grown me silent on the outside and I might not be able to say nothing.

I’d been either worried about or had been mad at Ma for a long time. But the closer I got to her, I just wanted to see her and hoped to find some peace between us somehow because I needed to feel something like that in a terrible way. I wondered about her for a long time on that trip and then somewhere on the road, my thoughts went to my brothers and where the winds may have taken them.

I thought about each one of them, and was curious to find out if they’d stayed in Shady, and how many of them now had families of their own, and if over time they’d left to find their own places and fortunes somewhere else, which I figured they all did.

I hoped luck had been good to them because, besides being my brothers, they were a good bunch of boys even if none of them ever came to visit me. I’d missed each of them more than they’d ever know, and I tried to figure like I’d done countless times what they’d aged to look like and such things because the last time I had seen them, most were just half-grown or less.

We were the closest of close growing up, sharing that one bedroom and generally one mattress, unless one or more were too young and slept in a bureau drawer or a pasteboard box beside Ma’s bed.

I was the oldest, and then there was Milton, James, Bernard, Franklin, Theodore and little Virgil. We were all kinds of different colors but we all carried the same last name Ma had, which was Purdue. Her first name was Rebecca, even though almost everybody in Shady called her Violet, which was her working name. Her closest friends called her Becca, which is the name I guessed she favored most to be called. Ma didn’t carry a middle name back then that I knew of.

Me, Frank and little Virgil were white-looking, mostly. Jimmy was shaded just like Ma, Milton was a red-brown color and Bernie was dark with slanted eyes. But Teddy was the one who stuck out the most from the rest of us, like the time when Ma let a photographer pay for her services with a sit-down photo of us. Teddy had green eyes, blond-red wiry hair and skin dark as a midnight with no moon. It was a black-and-white photo, but you could sense the different colors on him if you studied the picture where it hung in our living room.

Me and my brothers didn’t look much like brothers but we got along as brothers do, beating the tar out of each other one minute but not letting no one else put a hand on any of us the next. Local folks called us the Mutt Gang, and we didn’t look for trouble much, just mischief, but few boys or even grown men dared cross us after wronging us once.

Little Virgil was the only one of us who ever had a real dad in Shady because for some reason, a short feller with a small round curly head named Arthur Hoskins decided to face up to his responsibility about it.

I was so young then that my memory of Arthur Hoskins was fuzzy but I remember Ma wanting to get married quick to Arthur before he tried to get away. Arthur couldn’t go to the outhouse or take a walk by himself for a week before the nuptials without a man hired by the elders keeping an eye on him if Ma wasn’t around.

She told us that she’d finally found a decent man who could tolerate children and her occupation, so her and Arthur up and got hitched one hot Saturday afternoon under a walnut tree beside the Big Walker River. They even hauled in a real preacher from Abington on the back of a hay truck to do the ceremony. Ma insisted on a legal wedding.

Everybody in Shady Hollow went to it dressed up in the finest they owned as we all stood on the grassy riverbank.

Once it was over and dark set in, there was general high living and raucous behavior of all sorts. The elders paid for all of it.

But that short loud feller Ma had got hitched to got himself shot outside of McCauley’s Pavilion just before little Virgil was even crawling. Got shot square in the face. By a woman. Ma found out later that her dead husband was married to about a dozen other women besides her. One of them tracked him to Shady Hollow and killed him over it because he’d taken a good bit of her fortunes before he left.

The elders questioned Ma afterward over and over why a true professional con man like Arthur Hoskins, whose trade turned out to be robbing wealthy women, would want to marry a whore in Shady Hollow who didn’t have nothing but a bunch of hungry young’uns. Arthur’s other wives were all rich or within spitting distance of it. Ma kept telling the elders that she didn’t know, maybe Arthur just felt love for her and little Virgil.

They never bought into her explanation, I don’t think. Even grieving over her dead husband, Ma was summoned to a lot of elder meetings that year. Looking back, I believe that’s why they started getting suspicious of her.

Anyway, growing up, me and my brothers never called any man Dad or Papa or anything like that, but Ma told us to call some of the men who spent time around our second-floor apartment our “uncles,” so we did.

We had lots of uncles in Shady Hollow, and they came and went like leaves ride the river current.

They’d be there for a spell, giving Ma as much money as she could talk out of them and they’d eat her good Southern cooking and bounce a baby on a knee. They shared her bed, too, when she wasn’t working or when one of us wasn’t in it sick, and then one day we’d wake up and all sight and smell of them would be gone.

We’d stand quiet in our three-room apartment, looking out an open window, feeling the chill, watching theway the curtain would blow in and out. Ma had a cowbell nailed above the squeaky door to our apartment to keep better track of us. I guess that’s why they always left out a window—to keep from ringing that bell, same as we did when we’d sneak out.

Ma would shut the window tight all of a sudden and tell us that Uncle Pete or Uncle Shelby or Uncle Carl or Uncle whoever wasn’t bringing back breakfast because he wasn’t coming back. And that’s the last time any of us could speak their name as Ma would go to making grits on top of the coal stove.

She always made grits when we lost an uncle, not sure why because Ma hated grits and I was never fond of them, either. But we’d salt and pepper them and put butter or cheese in them and sit and eat quiet. Times were gonna be hard for a while. Grits signaled such times and we ate a lot of them between uncles.

Uncle Ray was my favorite uncle out of all of them.

Ma had told me the first day he moved in with us that he wasn’t my real uncle when I asked her, which meant he wasn’t my real father. But he could have been one to one of my brothers I guess—even though he didn’t look like none of us that I could see, except Teddy, because Teddy sort of looked like everybody.

Uncle Ray was getting a head start on being an old man in those times. But when he was younger, he’d went to a big college in Connecticut learning to be a doctor, Ma said. He got in some bad trouble not being able to pay off gambling and schooling debts to a bunch of serious fellers in New York City. Uncle Ray took off and I don’t know if he was ever a real doctor. But he could cut and stitch like no one else and he doctored in Shady whenever needed, even if he had to leave a card game to do it. And even if he was winning big or losing big, which he was admired for by some and not for by some others. I figured, too, sometimes that was the reason why Uncle Ray tended to be such a poor gambler.

He’d taught Ma and a couple of other gals to be his nurses for whenever he needed help, and he always told me that Ma was the best of all of them and it was a shame she never got an education. I remember both of them going off together in a rush at all times of the day or night once summoned for help from somebody, most usually for a woman in trouble. I guess I can best say that as far as making a living, Ma tended to the wants of men and the needs of women, all who came to Shady for such different reasons.

But before they worked together as doctor and nurse, it was clear from the first day Uncle Ray stepped foot in Shady that he liked Ma, because he was her best-paying customer. He doted on her more than most men ever did, buying her fancy garments or a hat or even flowers, stuff he didn’t need to buy because he always paid his turn with her in advance. I guess he just wanted to spend more money on her.

I didn’t think back then that Ma deep-down loved Uncle Ray like some folks you see do in movies. He didn’t love her in that way, either, but she seemed to care for him in a more than tolerable way. He stuck around long enough even when he wasn’t forced to, to show me how to do things like use that razor and how to load and shoot a gun—by not paying mind to what’s going on around you or the stirrings in you at that moment, but to just keep eyeballing the front sight and make sure it stayed in the middle of what you wanted to hit, and then keep squeezing that trigger nice and slow no matter if your hands were shaking because they were gonna be shaking if someone was shooting back at you.

“Nice and slow,” he said over and over.

I must have squeezed the trigger on his empty wheel gun a hundred or more times in Ma’s apartment as he’d lay a dime on the barrel. He told me I could keep the dime when I aimed in and squeezed the trigger and the dime was still balancing.

I eventually got to keep that ten cents, and got to pocket about a dollar’s worth more change over the weeks as we’d keep practicing. One day when we walked to the edge of Shady, he finally gave me a real bullet to put in his gun.