По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

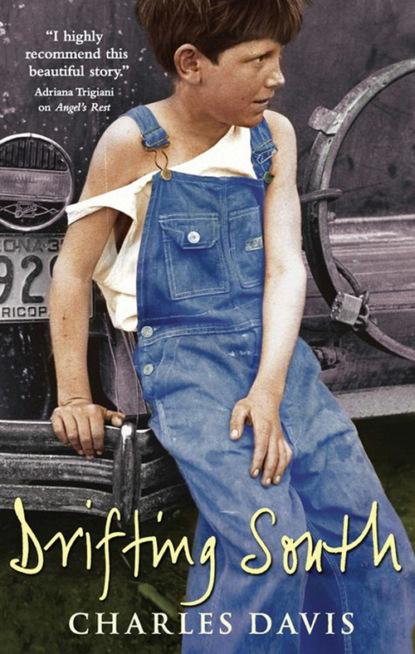

Drifting South

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Ma never believed Uncle Ray was as poor as an honest man, either, like he was so fond of saying at other times. He made a weekly wage from the elders for the doctoring that he did in Shady, and even though Uncle Ray always tended to gamble and drink away whatever money he’d make or win, Ma thought he squirreled away a little bit. But I guess after he got all busted up, I could see where he wasn’t able to make much of a living because he had to spend so much of the day with his feet up in air.

From what folks said, the only reason Uncle Ray was back with us at all was because the Shady elders convinced him to do so. The elders were all business, and quick at convincing. Word was that every one of them was from Ol’ Luke’s bloodline and they ran everything. The head of the elders was Tobias Chambers, and that’s who you’d go to if you were having some sort of problem you couldn’t handle by yourself. Once Mr. Chambers listened and nodded, that problem got fixed. And fixed for good. But if he didn’t nod, whatever problem you had was about to get dreadful worse.

Uncle Ray couldn’t walk for weeks after he left Ma and broke the elders’ contract with him to doctor in Shady. The elders tracked him to New Jersey and sent serious men to fetch him. Uncle Ray came back with both feet busted up, which displeased and troubled Ma, but Uncle Ray did seem to like staying with us more than before he tried to run off, or at least he acted like he did around Ma while he was hobbling around.

I walked toward the kitchen and could feel the pine planks underme moving up and down, and then I heard the muffled sound of loud music and static coming from the transistor radio in Ma’s bedroom. I looked over my left shoulder at the framed picture of Jesus that Ma had hung at the entrance of the narrow hallway. The picture of him with bright lights coming from his head was bouncing back and forth against the wall a little, and when the Jesus picture was agitated, is how me and my brothers could always tell for certain that Ma was busy working. Not just working, she was busy working. We’d learned from more than a couple of times when she’d lost business to our interruptions, that we weren’t to bother her until the Jesus picture calmed, unless one of us needed her for something of an emergency nature. She always said not to disturb her business at all over nothing serious if her door was closed and locked, because Ma never closed her door unless she was working. But we all knew as long as the Jesus picture was steady that we could peck on her locked door about this and that without too much fuss from one of her customers.

I pulled on one end of the twine that was hanging over a nail to level the picture of Jesus when Uncle Ray said, “Your momma made pork hash this morning, but your brothers wiped the kettle clean.”

“She make any bread?”

“They finished off the johnnycake, too.”

I stuck my head in the kitchen and saw the kettle and plates and forks soaking in a washtub, walked over to open the icebox, and there wasn’t a scrap of food in it except for a half-empty jar of mustard and the top stub of a pickle floating in a canning jar. Same as yesterday and the day before. Looking around in that icebox put me in a worse mood than I was in already. The thought of that hash made my mouth water.

“You been at Hoke’s this whole time?” Uncle Ray asked.

I walked back in the living room and nodded.

“Make any jingle manning the broom?”

Uncle Ray had put his straight razor, whetstone and flask away. He was staring at me with eyes set close together like a hawk while training his new wide mustache that went all the way down to his chin. Wasn’t his business whether I made anything or not so I kept quiet, but the fact was I didn’t make anything.

“Until they let you back in the poker games, that violin is what’ll earn you a living. The way you fiddle on it all the time, you should be down in the saloons making it work for you.”

I’d been thinking about trying my luck in the music business, being the gambling business had been going so poorly. Uncle Ray had told me I had an ear for making music the first day he’d gave me that fiddle after winning it in a knock-rummy game. I was playing “Cripple Creek” and “Don’t Hit Your Granny With a Big Ol’ Stick” and a bunch of other old mountain tunes before that evening was over.

Music did come easy to me, the same way Ma had always fretted that most things did to me. I wasn’t as sure about that as she was, but she feared the easy, because she believed people became lazy if they don’t end up venturing to where things are hard for them. And to Ma, there weren’t but a hair of difference between laziness and evilness. She kept all her boys busy and I guess tried her best not to raise lazy, evil sons, but I believe it was a bigger job than one woman by herself could sometimes handle.

I just figured music came easy to me because I’d always loved to listen to it so much. But what I couldn’t do was sing like good singers can, so I didn’t see profit or future in making music, and my goal in life was to make money however it could be made the quickest and the easiest and the most. I wanted to be rich because I’d seen how the rich are treated so different than folks are with nothing but holes in their pockets, and I’d never owned nothing without a hole in it somewhere.

Anyway, I was still standing there in the hall next to Ma’s kitchen and had just gotten back from Hoke’s Billiards Emporium. I’d been there all the last night and into that morning, waiting on a new shooter I’d spotted coming into town with a loud cowboy hat and fancy cue.

Hoke had rented me a broom to lean on as a prop so I might be able to hustle up a game and not look like a real player. He told me that he’d have to eyeball the shooter I was hunting before he’d assign him to me, because the hat and cue could be a ruse.

Even though Hoke knew I was one of the better poker players in Shady—so good it was rare anymore when I could get anybody to deal me a hand—he thought I needed more time watching the other shooters.

It was the same way I’d learned to play poker, by studying the players as much as the cards, and by abiding by the unwritten rules more than the written ones. Like I learned young that cheating’s always fair, an unwritten rule, but only as long as you can get away with it.

After getting too famous for my own good at poker, I was determined to not let the same thing happen shooting pool. The one poker lesson I picked up too late was not to win as often as I could. That was one hard lesson Hoke drove into me every chance he got. I’d been trying as hard as I could to beat off the nickname I’d taken on: Luck.

Nobody wanted to play a sporting game of anything against a feller nicknamed Luck.

Hoke always got his forty percent share from the takings in his place. The bad thing for me was if I didn’t make nothing, I’d have to pay him a quarter just to lean on his broom, it being part of my role as the floor sweeper who’d just like to shoot a game for a cold bottle of pop while on break. He controlled the whole place while watching eight tables at once from the window of his small upstairs office. Hoke was as round as he was tall, and he smoked two cigarettes at a time by the way he always had one lit, and he reminded me of those puppet masters who would float into Shady now and then with all of those strings dangling from their fingers. Everybody who worked for Hoke were his puppets. And the ones who came through the door just looking to shoot an hour away became his puppets, too, if they weren’t mindful. One game or one drink too many, and Hoke would own them and everything they had.

But my mark never showed. I suspected he got sidetracked early by the whores and now probably didn’t have a penny left on him, and that’s why I was in a surly mood that late Sunday morning when I got back to Ma’s apartment.

I turned my eyes away from Uncle Ray to a pair of muddy trousers stuffed with straw hanging over the kitchen door. They looked like they’d been run over by the tire tracks on them. I’d seen odder things in Ma’s apartment, but couldn’t figure why half of a scarecrow would be dangling in her kitchen. I figured it was a charm Ma had hung up to ward off some sort of evil.

“Want a lesson?” Uncle Ray asked. He didn’t say it too loud because he only taught things when Ma was away or working. Ma frowned on the lessons he taught, except for the times he’d tried to teach me to read and write, which I never had any interest in.

“I got to find something to eat,” I said, studying on those burlap pants.

“I’m about to teach you something about being able to keep a full belly. But if you think tending to your empty belly at this particular moment is more important, then we’ll forget about it.”

Ma always said Uncle Ray was half angel and half outlaw. He had to be the most educated man in Shady because he’d went to college and was the only person who knew what to do with all the things in a doctor bag. And he always liked to talk up a storm in his half Southern and half Yankee accent about things in the world nobody else knew much about or cared much about. I feared he was going to preach book learning to me again and pull out a pen and pad of paper like he’d do from time to time.

“Teach what?”

“You can’t scare up a game of cards, aren’t having much luck at the tables and you don’t want to fiddle for your breakfast, so I thought you might want to learn how to use this.”

Uncle Ray stood from Ma’s couch and turned a half step. He pulled his straight razor from a sheath he carried in the small of his back. He put it up to the window light where it caught a glare and then he stared at me. I’d just seen him honing on it but he made a pretty big deal out of flashing it around.

He walked into the kitchen and over the next hour I soon forgot about my empty stomach as he made me practice over and over how to pull a razor and hold it. Then he had me walk up to that pair of pants a hundred times practicing how to cut the side of a back pocket without cutting in too far but far enough.

“Pair of pants like this, you don’t cut the bottom, you cut the side. Not too far and it has to be done quick,” he said.

Before I started the actual cutting, he took his razor from me and he cut both pockets so fast that I missed how he did it, even thought I was watching with wide eyes. I never even saw the razor in his hand.

“Goddamn, Uncle Ray,” I said.

“Sew them up,” he said.

After I sewed those pockets up, which he showed me how to do, too, he gave me back the razor and then he moved my fingers around to the right position.

“Keep the handle against your wrist, and your thumb and middle knuckle of your pointing finger way down on the blade. That way no one will know what you’re carrying and you’ll cut only as deep as necessary. You slash a man’s backside wide-open with a razor and I can assure you he’ll be prone to kill you over it.”

“You ever done that?”

“I never got the lesson you’re getting right now, let’s put it that way.”

I practiced and practiced with him telling me how to approach those stuffed pants like I was just walking normal, and then go in fast with that blade until the pocket got cut without the pants moving any, and I didn’t cut anything under it. When I started getting good, he gave me one of his old razors and a smooth whetstone to keep for my own, but that’s when we both heard Ma’s radio turn off and she walked in from the back bedroom. Uncle Ray fought the pants into an empty pantry cupboard and both of us tucked our razors away.

Ma was wearing her red shiny robe, and wrapped herself up in it tight when she saw me. She kept looking back and forth at me and Uncle Ray, but then stopped at me.

“Didn’t hear you come in, sugar. You make any money last night?” she asked.

I shook my head, but I would have shook my head whether I made anything or not, because Ma was more likely to give me money when I wasn’t making money.

“You lose any?” She looked at me hard and long when she asked that.

“Just the quarter.”

“You eat?”

“Had a few peanuts last night is all.”

Ma shook her head, dug in her robe pocket and then stuck out her hand. She gave me several bills folded in half.