По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

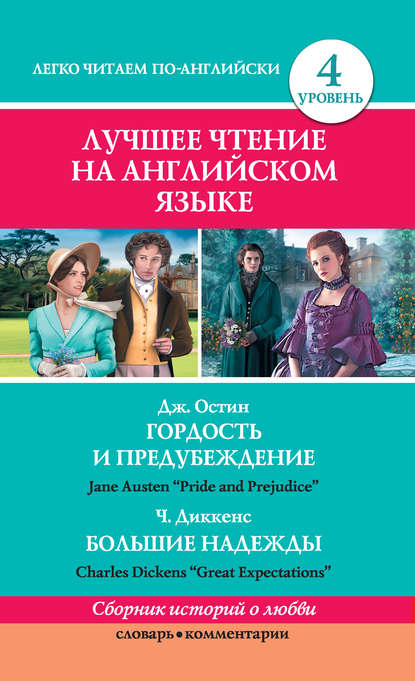

Гордость и предубеждение / Pride and Prejudice. Great Expectations / Большие надежды

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You can say what you like,” returned the sergeant, standing coolly looking at him with his arms folded, “but you’ll have opportunity enough to say about it, and hear about it, you know.”

“A man can’t starve; at least I can’t. I took some wittles, at the village over there.”

“You mean stole,” said the sergeant.

“And I’ll tell you where from. From the blacksmith’s.”

“Halloa!” said the sergeant, staring at Joe.

“Halloa, Pip!” said Joe, staring at me.

“It was some wittles – that’s what it was – and liquor, and a pie.”

“You’re welcome,” returned Joe, “We don’t know what you have done, but we wouldn’t have you starved, poor miserable fellow. Would us, Pip?”

Something clicked in the man’s throat, and he turned his back.

Chapter 6

The fear of losing Joe’s confidence, and of sitting in the chimney corner at night staring at my forever lost companion and friend, tied up my tongue. In a word, I was too cowardly to tell Joe the truth.

As I was sleepy before we were far away from the prison-ship, Joe took me on his back again and carried me home.

By that time, I was fast asleep, and through waking in the heat and lights and noise of tongues. As I came to myself (with the aid of a heavy thump between the shoulders), I found Joe telling them about the convict’s confession, and all the visitors suggesting different ways by which he had got into the pantry. Everybody agreed that it must be so.

Chapter 7

When I was old enough, I was to be apprenticed to Joe. Therefore, I was not only odd-boy about the forge, but if any neighbor happened to want an extra boy to frighten birds, or pick up stones, or do any such job, I was favoured with the employment.

“Didn’t you ever go to school, Joe, when you were as little as me?” asked I one day.

“No, Pip.”

“Why didn’t you ever go to school?”

“Well, Pip,” said Joe, taking up the poker, and settling himself to his usual occupation when he was thoughtful; “I’ll tell you. My father, Pip, liked to drink much. You’re listening and understanding, Pip?”

“Yes, Joe.”

“So my mother and me we ran away from my father several times. Sometimes my mother said, ‘Joe, you shall have some schooling, child,’ and she’d put me to school. But my father couldn’t live without us. So, he’d come with a crowd and took us from the houses where we were. He took us home and hammered us. You see, Pip, it was a drawback on my learning.[23 - it was a drawback on my learning – моему ученью это здорово мешало]”

“Certainly, poor Joe!”

“My father didn’t make objections to my going to work; so I went to work. In time I was able to keep him, and I kept him till he went off.”

Joe’s blue eyes turned a little watery; he rubbed first one of them, and then the other, in a most uncomfortable manner, with the round knob on the top of the poker.

“I got acquainted with your sister,” said Joe, “living here alone. Now, Pip,” – Joe looked firmly at me as if he knew I was not going to agree with him; – “your sister is a fine figure of a woman.[24 - a fine figure of a woman – видная женщина]”

I could think of nothing better to say than “I am glad you think so, Joe.”

“So am I,” returned Joe. “That’s it. You’re right, old chap! When I got acquainted with your sister, she was bringing you up by hand. Very kind of her too, all the folks said, and I said, along with all the folks.”

I said, “Never mind me,[25 - Never mind me. – Ну что говорить обо мне.] Joe.”

“When I offered to your sister to keep company, and to be asked in church at such times as she was willing and ready to come to the forge, I said to her, ‘And bring the poor little child. God bless the poor little child,’ I said to your sister, ‘there’s room for him at the forge!’”

I broke out crying and begging pardon, and hugged Joe round the neck: who dropped the poker to hug me, and to say, “We are the best friends; aren’t we, Pip? Don’t cry, old chap!”

Joe resumed,

“Well, you see; here we are! Your sister a master-mind.[26 - Your sister a master-mind. – Твоя сестра – ума палата.] A master-mind.”

“However,” said Joe, rising to replenish the fire; “Here comes the mare!”

Mrs. Joe and Uncle Pumblechook was soon near, covering the mare with a cloth, and we were soon all in the kitchen.

“Now,” said Mrs. Joe with haste and excitement, and throwing her bonnet back on her shoulders, “if this boy isn’t grateful this night, he never will be! Miss Havisham[27 - Havisham – Хэвишем] wants this boy to go and play in her house. And of course he’s going.”

I had heard of Miss Havisham – everybody for miles round had heard of her – as an immensely rich and grim lady who lived in a large and dismal house barricaded against robbers, and who led a life of seclusion.

“I wonder how she come to know Pip!” said Joe, astounded.

“Who said she knew him?” cried my sister. “Couldn’t she ask Uncle Pumblechook if he knew of a boy to go and play there? Uncle Pumblechook thinks that that is the boy’s fortune. So he offered to take him into town tonight in his own chaise-cart, and to take him with his own hands to Miss Havisham’s tomorrow morning.”

* * *

I was then delivered over to Mr. Pumblechook, who formally received me as if he were the Sheriff. He said: “Boy, be forever grateful to all friends, but especially unto them which brought you up by hand!”

“Good-bye, Joe!”

“God bless you, Pip, old chap!”

I had never parted from him before, and I could at first see no stars from the chaise-cart. I did not understand why I was going to play at Miss Havisham’s, and what I was expected to play at.

Chapter 8

Mr. Pumblechook and I breakfasted at eight o’clock in the parlor behind the shop. I considered Mr. Pumblechook wretched company.[28 - I considered Mr. Pumblechook wretched company. – В обществе мистера Памблчука я чувствовал себя отвратительно.] On my politely bidding him Good morning, he said, “Seven times nine, boy?[29 - Seven times nine, boy? – Сколько будет семью девять, мальчик?]” And how should I be able to answer, in a strange place, on an empty stomach![30 - on an empty stomach – на пустой желудок] I was very hungry, but the math[31 - math = mathematics – математика] lesson lasted all through the breakfast. “Seven?” “And four?” “And eight?” “And six?” “And two?” “And ten?” And so on.

For such reasons, I was very glad when ten o’clock came and we started for Miss Havisham’s. Within a quarter of an hour we came to Miss Havisham’s house, which was of old brick, and dismal, and had a great many iron bars to it. While we waited at the gate, Mr. Pumblechook said, “And fourteen?” but I pretended not to hear him.

A window was raised, and a clear voice demanded “What name?” To which my conductor replied, “Pumblechook.” The voice returned, “Quite right,” and the window was shut again, and a young lady came across the courtyard, with keys in her hand.

“This,” said Mr. Pumblechook, “is Pip.”

“This is Pip, is it?” returned the young lady, who was very pretty and seemed very proud; “come in, Pip.”

Mr. Pumblechook was coming in also, when she stopped him with the gate.

“A man can’t starve; at least I can’t. I took some wittles, at the village over there.”

“You mean stole,” said the sergeant.

“And I’ll tell you where from. From the blacksmith’s.”

“Halloa!” said the sergeant, staring at Joe.

“Halloa, Pip!” said Joe, staring at me.

“It was some wittles – that’s what it was – and liquor, and a pie.”

“You’re welcome,” returned Joe, “We don’t know what you have done, but we wouldn’t have you starved, poor miserable fellow. Would us, Pip?”

Something clicked in the man’s throat, and he turned his back.

Chapter 6

The fear of losing Joe’s confidence, and of sitting in the chimney corner at night staring at my forever lost companion and friend, tied up my tongue. In a word, I was too cowardly to tell Joe the truth.

As I was sleepy before we were far away from the prison-ship, Joe took me on his back again and carried me home.

By that time, I was fast asleep, and through waking in the heat and lights and noise of tongues. As I came to myself (with the aid of a heavy thump between the shoulders), I found Joe telling them about the convict’s confession, and all the visitors suggesting different ways by which he had got into the pantry. Everybody agreed that it must be so.

Chapter 7

When I was old enough, I was to be apprenticed to Joe. Therefore, I was not only odd-boy about the forge, but if any neighbor happened to want an extra boy to frighten birds, or pick up stones, or do any such job, I was favoured with the employment.

“Didn’t you ever go to school, Joe, when you were as little as me?” asked I one day.

“No, Pip.”

“Why didn’t you ever go to school?”

“Well, Pip,” said Joe, taking up the poker, and settling himself to his usual occupation when he was thoughtful; “I’ll tell you. My father, Pip, liked to drink much. You’re listening and understanding, Pip?”

“Yes, Joe.”

“So my mother and me we ran away from my father several times. Sometimes my mother said, ‘Joe, you shall have some schooling, child,’ and she’d put me to school. But my father couldn’t live without us. So, he’d come with a crowd and took us from the houses where we were. He took us home and hammered us. You see, Pip, it was a drawback on my learning.[23 - it was a drawback on my learning – моему ученью это здорово мешало]”

“Certainly, poor Joe!”

“My father didn’t make objections to my going to work; so I went to work. In time I was able to keep him, and I kept him till he went off.”

Joe’s blue eyes turned a little watery; he rubbed first one of them, and then the other, in a most uncomfortable manner, with the round knob on the top of the poker.

“I got acquainted with your sister,” said Joe, “living here alone. Now, Pip,” – Joe looked firmly at me as if he knew I was not going to agree with him; – “your sister is a fine figure of a woman.[24 - a fine figure of a woman – видная женщина]”

I could think of nothing better to say than “I am glad you think so, Joe.”

“So am I,” returned Joe. “That’s it. You’re right, old chap! When I got acquainted with your sister, she was bringing you up by hand. Very kind of her too, all the folks said, and I said, along with all the folks.”

I said, “Never mind me,[25 - Never mind me. – Ну что говорить обо мне.] Joe.”

“When I offered to your sister to keep company, and to be asked in church at such times as she was willing and ready to come to the forge, I said to her, ‘And bring the poor little child. God bless the poor little child,’ I said to your sister, ‘there’s room for him at the forge!’”

I broke out crying and begging pardon, and hugged Joe round the neck: who dropped the poker to hug me, and to say, “We are the best friends; aren’t we, Pip? Don’t cry, old chap!”

Joe resumed,

“Well, you see; here we are! Your sister a master-mind.[26 - Your sister a master-mind. – Твоя сестра – ума палата.] A master-mind.”

“However,” said Joe, rising to replenish the fire; “Here comes the mare!”

Mrs. Joe and Uncle Pumblechook was soon near, covering the mare with a cloth, and we were soon all in the kitchen.

“Now,” said Mrs. Joe with haste and excitement, and throwing her bonnet back on her shoulders, “if this boy isn’t grateful this night, he never will be! Miss Havisham[27 - Havisham – Хэвишем] wants this boy to go and play in her house. And of course he’s going.”

I had heard of Miss Havisham – everybody for miles round had heard of her – as an immensely rich and grim lady who lived in a large and dismal house barricaded against robbers, and who led a life of seclusion.

“I wonder how she come to know Pip!” said Joe, astounded.

“Who said she knew him?” cried my sister. “Couldn’t she ask Uncle Pumblechook if he knew of a boy to go and play there? Uncle Pumblechook thinks that that is the boy’s fortune. So he offered to take him into town tonight in his own chaise-cart, and to take him with his own hands to Miss Havisham’s tomorrow morning.”

* * *

I was then delivered over to Mr. Pumblechook, who formally received me as if he were the Sheriff. He said: “Boy, be forever grateful to all friends, but especially unto them which brought you up by hand!”

“Good-bye, Joe!”

“God bless you, Pip, old chap!”

I had never parted from him before, and I could at first see no stars from the chaise-cart. I did not understand why I was going to play at Miss Havisham’s, and what I was expected to play at.

Chapter 8

Mr. Pumblechook and I breakfasted at eight o’clock in the parlor behind the shop. I considered Mr. Pumblechook wretched company.[28 - I considered Mr. Pumblechook wretched company. – В обществе мистера Памблчука я чувствовал себя отвратительно.] On my politely bidding him Good morning, he said, “Seven times nine, boy?[29 - Seven times nine, boy? – Сколько будет семью девять, мальчик?]” And how should I be able to answer, in a strange place, on an empty stomach![30 - on an empty stomach – на пустой желудок] I was very hungry, but the math[31 - math = mathematics – математика] lesson lasted all through the breakfast. “Seven?” “And four?” “And eight?” “And six?” “And two?” “And ten?” And so on.

For such reasons, I was very glad when ten o’clock came and we started for Miss Havisham’s. Within a quarter of an hour we came to Miss Havisham’s house, which was of old brick, and dismal, and had a great many iron bars to it. While we waited at the gate, Mr. Pumblechook said, “And fourteen?” but I pretended not to hear him.

A window was raised, and a clear voice demanded “What name?” To which my conductor replied, “Pumblechook.” The voice returned, “Quite right,” and the window was shut again, and a young lady came across the courtyard, with keys in her hand.

“This,” said Mr. Pumblechook, “is Pip.”

“This is Pip, is it?” returned the young lady, who was very pretty and seemed very proud; “come in, Pip.”

Mr. Pumblechook was coming in also, when she stopped him with the gate.