По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

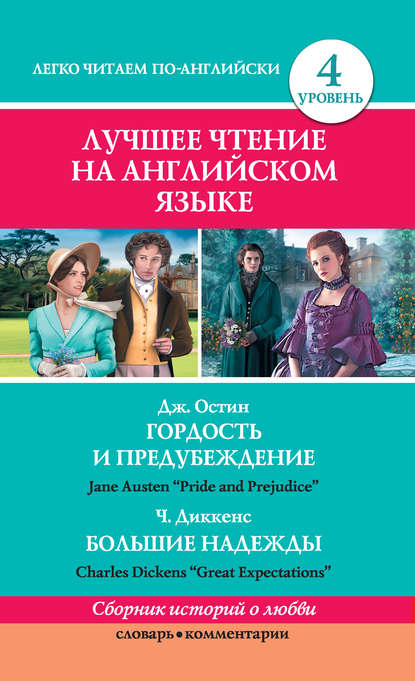

Гордость и предубеждение / Pride and Prejudice. Great Expectations / Большие надежды

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Large or small?”

“Immense,” said I. “And they fought for veal-cutlets out of a silver basket.”

Mr. Pumblechook and Mrs. Joe stared at one another again, in utter amazement. I was perfectly frantic and would have told them anything.

“Where was this coach, in the name of gracious?[44 - in the name of gracious – боже милостивый]” asked my sister.

“In Miss Havisham’s room.” They stared again. “But there weren’t any horses to it.”

“Can this be possible, uncle?” asked Mrs. Joe. “What can the boy mean?”

“I’ll tell you, Mum,” said Mr. Pumblechook. “My opinion is, it’s a sedan-chair.[45 - sedan-chair – портшез (лёгкое переносное кресло, в котором можно сидеть полулёжа; паланкин)] She’s flighty, you know – very flighty – quite flighty enough to pass her days in a sedan-chair.”

“Did you ever see her in it, uncle?” asked Mrs. Joe.

“How could I,” he returned, “when I never see her in my life?”

“Goodness, uncle! And yet you have spoken to her?”

“Why, don’t you know,” said Mr. Pumblechook, “that when I have been there, I have been took up to the outside of her door, and the door has stood ajar, and she has spoke to me that way. Don’t say you don’t know that, Mum. But the boy went there to play. What did you play at, boy?”

“We played with flags,” I said.

“Flags!” echoed my sister.

“Yes,” said I. “Estella waved a blue flag, and I waved a red one, and Miss Havisham waved one sprinkled all over with little gold stars, out at the coach-window. And then we all waved our swords and hurrahed.”

“Swords!” repeated my sister. “Where did you get swords from?”

“Out of a cupboard,” said I. “And I saw pistols in it – and jam – and pills. And there was no daylight in the room, but it was all lighted up with candles.”

“That’s true, Mum,” said Mr. Pumblechook, with a grave nod. “That’s the state of the case, for that much I’ve seen myself.” And then they both stared at me, and I stared at them.

Now, when I saw Joe open his blue eyes and roll them all round the kitchen in helpless amazement; but only as regarded him – not in the least as regarded the other two. Towards Joe, and Joe only, I considered myself a young monster. They had no doubt that Miss Havisham would “do something” for me. My sister stood out for “property.” Mr. Pumblechook was in favour of a handsome premium[46 - handsome premium – щедрая плата] for schooling.

After Mr. Pumblechook had driven off, and when my sister was washing up, I went into the forge to Joe, and remained by him until he had done for the night. Then I said, “Before the fire goes out, Joe, I should like to tell you something.”

“Should you, Pip?” said Joe. “Then tell me. What is it, Pip?”

“Joe,” said I, taking hold of his shirt sleeve, and twisting it between my finger and thumb, “you remember all that about Miss Havisham’s?”

“Remember?” said Joe. “I believe you! Wonderful!”

“It’s a terrible thing, Joe; it isn’t true.”

“What are you telling of, Pip?” cried Joe, falling back in the greatest amazement. “You don’t mean to say it’s – ”

“Yes I do; it’s lies, Joe.”

“But not all of it?” I stood shaking my head. “But at least there were dogs, Pip? Come, Pip,” said Joe, “at least there were dogs?”

“No, Joe.”

“A dog?” said Joe. “A puppy? Come?”

“No, Joe, there was nothing at all of the kind. It’s terrible, Joe; isn’t it?”

“Terrible?” cried Joe. “Awful! What possessed you?”

“I don’t know what possessed me, Joe,” I replied, letting his shirt sleeve go, and sitting down in the ashes at his feet, hanging my head; “but I wish my boots weren’t so thick nor my hands so coarse.”

And then I told Joe that I felt very miserable, and that I hadn’t been able to explain myself to Mrs. Joe and Pumblechook, who were so rude to me, and that there had been a beautiful young lady at Miss Havisham’s who was dreadfully proud, and that she had said I was common, and that I knew I was common, and that I wished I was not common, and that the lies had come of it somehow, though I didn’t know how.

“There’s one thing you may be sure of, Pip,” said Joe, after some rumination, “namely, that lies is lies. Don’t you tell more of them, Pip. That isn’t the way to get out of being common, old chap. But you are uncommon in some things. You’re uncommon small. There was a flag, perhaps?”

“No, Joe.”

“I’m sorry there wasn’t a flag, Pip. Look here, Pip, at what is said to you by a true friend. Don’t tell more lies, Pip, and live well and die happy.”

“You are not angry with me, Joe?”

“No, old chap. But when you go up stairs to bed, Pip, please think about my words. That’s all, old chap, and never do it more.”

When I got up to my little room and said my prayers, I did not forget Joe’s recommendation. I thought how Joe and my sister were sitting in the kitchen, and how I had come up to bed from the kitchen, and how Miss Havisham and Estella never sat in a kitchen, but were far above the level of such common doings.[47 - were far above the level of such common doings – были намного выше такой обыкновенной жизни]

That was a memorable day to me, for it made great changes in me. Pause you who read this, and think for a moment of the long chain of iron or gold, of thorns or flowers, that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day.

Chapter 10

Of course there was a public-house[48 - public-house – трактир, харчевня] in the village, and of course Joe liked sometimes to smoke his pipe there. I had received strict orders from my sister to call for him at the Three Jolly Bargemen,[49 - Three Jolly Bargemen – “Три Весёлых матроса” (название трактира)] that evening, on my way from school, and bring him home. To the Three Jolly Bargemen, therefore, I directed my steps.

There was a bar at the Jolly Bargemen, with some alarmingly long chalk scores in it on the wall at the side of the door, which seemed to me to be never paid off.

It was Saturday night, I found the landlord looking rather sadly at these records; but as my business was with Joe and not with him, I merely wished him good evening, and passed into the common room at the end of the passage, where there was a bright large kitchen fire, and where Joe was smoking his pipe in company with Mr. Wopsle and a stranger. Joe greeted me as usual with “Halloa, Pip, old chap!” and the moment he said that, the stranger turned his head and looked at me.

He was a secret-looking man whom I had never seen before. His head was all on one side, and one of his eyes was half shut up, as if he were taking aim at something with an invisible gun. He had a pipe in his mouth, and he took it out, and, after slowly blowing all his smoke away and looking hard at me all the time, nodded. So, I nodded, and then he nodded again.

“You were saying,” said the strange man, turning to Joe, “that you were a blacksmith.”

“Yes. I said it, you know,” said Joe.

“What’ll you drink, Mr. – ? You didn’t mention your name, by the way.”

Joe mentioned it now, and the strange man called him by it. “What’ll you drink, Mr. Gargery? At my expense?[50 - At my expense? – За мой счёт?]”

“Well,” said Joe, “to tell you the truth, I am not much in the habit of drinking at anybody’s expense but my own.”

“Habit? No,” returned the stranger, “but once and away, and on a Saturday night too. Come!”

“Immense,” said I. “And they fought for veal-cutlets out of a silver basket.”

Mr. Pumblechook and Mrs. Joe stared at one another again, in utter amazement. I was perfectly frantic and would have told them anything.

“Where was this coach, in the name of gracious?[44 - in the name of gracious – боже милостивый]” asked my sister.

“In Miss Havisham’s room.” They stared again. “But there weren’t any horses to it.”

“Can this be possible, uncle?” asked Mrs. Joe. “What can the boy mean?”

“I’ll tell you, Mum,” said Mr. Pumblechook. “My opinion is, it’s a sedan-chair.[45 - sedan-chair – портшез (лёгкое переносное кресло, в котором можно сидеть полулёжа; паланкин)] She’s flighty, you know – very flighty – quite flighty enough to pass her days in a sedan-chair.”

“Did you ever see her in it, uncle?” asked Mrs. Joe.

“How could I,” he returned, “when I never see her in my life?”

“Goodness, uncle! And yet you have spoken to her?”

“Why, don’t you know,” said Mr. Pumblechook, “that when I have been there, I have been took up to the outside of her door, and the door has stood ajar, and she has spoke to me that way. Don’t say you don’t know that, Mum. But the boy went there to play. What did you play at, boy?”

“We played with flags,” I said.

“Flags!” echoed my sister.

“Yes,” said I. “Estella waved a blue flag, and I waved a red one, and Miss Havisham waved one sprinkled all over with little gold stars, out at the coach-window. And then we all waved our swords and hurrahed.”

“Swords!” repeated my sister. “Where did you get swords from?”

“Out of a cupboard,” said I. “And I saw pistols in it – and jam – and pills. And there was no daylight in the room, but it was all lighted up with candles.”

“That’s true, Mum,” said Mr. Pumblechook, with a grave nod. “That’s the state of the case, for that much I’ve seen myself.” And then they both stared at me, and I stared at them.

Now, when I saw Joe open his blue eyes and roll them all round the kitchen in helpless amazement; but only as regarded him – not in the least as regarded the other two. Towards Joe, and Joe only, I considered myself a young monster. They had no doubt that Miss Havisham would “do something” for me. My sister stood out for “property.” Mr. Pumblechook was in favour of a handsome premium[46 - handsome premium – щедрая плата] for schooling.

After Mr. Pumblechook had driven off, and when my sister was washing up, I went into the forge to Joe, and remained by him until he had done for the night. Then I said, “Before the fire goes out, Joe, I should like to tell you something.”

“Should you, Pip?” said Joe. “Then tell me. What is it, Pip?”

“Joe,” said I, taking hold of his shirt sleeve, and twisting it between my finger and thumb, “you remember all that about Miss Havisham’s?”

“Remember?” said Joe. “I believe you! Wonderful!”

“It’s a terrible thing, Joe; it isn’t true.”

“What are you telling of, Pip?” cried Joe, falling back in the greatest amazement. “You don’t mean to say it’s – ”

“Yes I do; it’s lies, Joe.”

“But not all of it?” I stood shaking my head. “But at least there were dogs, Pip? Come, Pip,” said Joe, “at least there were dogs?”

“No, Joe.”

“A dog?” said Joe. “A puppy? Come?”

“No, Joe, there was nothing at all of the kind. It’s terrible, Joe; isn’t it?”

“Terrible?” cried Joe. “Awful! What possessed you?”

“I don’t know what possessed me, Joe,” I replied, letting his shirt sleeve go, and sitting down in the ashes at his feet, hanging my head; “but I wish my boots weren’t so thick nor my hands so coarse.”

And then I told Joe that I felt very miserable, and that I hadn’t been able to explain myself to Mrs. Joe and Pumblechook, who were so rude to me, and that there had been a beautiful young lady at Miss Havisham’s who was dreadfully proud, and that she had said I was common, and that I knew I was common, and that I wished I was not common, and that the lies had come of it somehow, though I didn’t know how.

“There’s one thing you may be sure of, Pip,” said Joe, after some rumination, “namely, that lies is lies. Don’t you tell more of them, Pip. That isn’t the way to get out of being common, old chap. But you are uncommon in some things. You’re uncommon small. There was a flag, perhaps?”

“No, Joe.”

“I’m sorry there wasn’t a flag, Pip. Look here, Pip, at what is said to you by a true friend. Don’t tell more lies, Pip, and live well and die happy.”

“You are not angry with me, Joe?”

“No, old chap. But when you go up stairs to bed, Pip, please think about my words. That’s all, old chap, and never do it more.”

When I got up to my little room and said my prayers, I did not forget Joe’s recommendation. I thought how Joe and my sister were sitting in the kitchen, and how I had come up to bed from the kitchen, and how Miss Havisham and Estella never sat in a kitchen, but were far above the level of such common doings.[47 - were far above the level of such common doings – были намного выше такой обыкновенной жизни]

That was a memorable day to me, for it made great changes in me. Pause you who read this, and think for a moment of the long chain of iron or gold, of thorns or flowers, that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day.

Chapter 10

Of course there was a public-house[48 - public-house – трактир, харчевня] in the village, and of course Joe liked sometimes to smoke his pipe there. I had received strict orders from my sister to call for him at the Three Jolly Bargemen,[49 - Three Jolly Bargemen – “Три Весёлых матроса” (название трактира)] that evening, on my way from school, and bring him home. To the Three Jolly Bargemen, therefore, I directed my steps.

There was a bar at the Jolly Bargemen, with some alarmingly long chalk scores in it on the wall at the side of the door, which seemed to me to be never paid off.

It was Saturday night, I found the landlord looking rather sadly at these records; but as my business was with Joe and not with him, I merely wished him good evening, and passed into the common room at the end of the passage, where there was a bright large kitchen fire, and where Joe was smoking his pipe in company with Mr. Wopsle and a stranger. Joe greeted me as usual with “Halloa, Pip, old chap!” and the moment he said that, the stranger turned his head and looked at me.

He was a secret-looking man whom I had never seen before. His head was all on one side, and one of his eyes was half shut up, as if he were taking aim at something with an invisible gun. He had a pipe in his mouth, and he took it out, and, after slowly blowing all his smoke away and looking hard at me all the time, nodded. So, I nodded, and then he nodded again.

“You were saying,” said the strange man, turning to Joe, “that you were a blacksmith.”

“Yes. I said it, you know,” said Joe.

“What’ll you drink, Mr. – ? You didn’t mention your name, by the way.”

Joe mentioned it now, and the strange man called him by it. “What’ll you drink, Mr. Gargery? At my expense?[50 - At my expense? – За мой счёт?]”

“Well,” said Joe, “to tell you the truth, I am not much in the habit of drinking at anybody’s expense but my own.”

“Habit? No,” returned the stranger, “but once and away, and on a Saturday night too. Come!”