По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

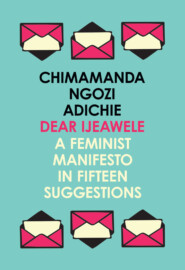

Half of a Yellow Sun, Americanah, Purple Hibiscus: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Three-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Thank you.’ He still stood there.

‘Are you driving? No, you’re not, I remember. You’ll take the train.’ She laughed an awkward laugh.

‘Yes, I’m taking the train.’

‘Have a safe trip.’

‘Yes. All right then.’

Olanna watched him leave, and long after his car had reversed out of the compound, she stood at the door, watching a bird with a blood-red breast, perched on the lawn.

In the morning, Odenigbo woke her up by taking her finger in his mouth. She opened her eyes; she could see the smoky light of dawn through the curtains.

‘If you won’t marry me, nkem, then let’s have a child,’ he said.

Her finger muffled his voice, so she pulled her hand away and sat up to stare at him, his wide chest, his sleep-swollen eyes, to make sure she had heard him properly.

‘Let’s have a child,’ he said again. ‘A little girl just like you, and we will call her Obianuju because she will complete us.’

Olanna had wanted to give the scent of his mother’s visit some time to diffuse before telling him she wanted to have a child, and yet here he was, voicing her own desire before she could. She looked at him in wonder. This was love: a string of coincidences that gathered significance and became miracles. ‘Or a little boy,’ she said finally.

Odenigbo pulled her down and they lay side by side, not touching. She could hear the raspy caw-caw-caw of the blackbirds that ate the pawpaws in the garden.

‘Let’s have Ugwu bring us breakfast in bed,’ he said. ‘Or is this one of your Sundays of faith?’ He was smiling his gently indulgent smile, and she reached out and traced his lower lip with the slight fuzz underneath. He liked to tease her about religion’s not being a social service, because she went to church only for St Vincent de Paul meetings, when she took Ugwu with her for the drive through dirt paths in nearby villages to give away yams and rice and old clothes.

‘I won’t go today,’ she said.

‘Good. Because we have work to do.’

She closed her eyes because he was straddling her now and as he moved, languorously at first and then forcefully, he whispered, ‘We will have a brilliant child, nkem, a brilliant child,’ and she said, ‘Yes, yes’. Afterwards, she felt happy knowing that some of the sweat on her body was his and some of the sweat on his body was hers. Each time, after he slipped out of her, she pressed her legs together, crossed them at her ankles, and took deep breaths, as if the movement of her lungs would urge conception on. But they did not conceive a child, she knew. The sudden thought that something might be wrong with her body wrapped itself around her, dampened her.

6 (#u3c1576f1-c916-57b7-bb43-a63c028a7109)

Richard ate the pepper soup slowly. After he had spooned up the pieces of tripe, he raised the glass bowl to his lips and drank the broth. His nose was running, there was a delicious burning on his tongue, and he knew his face was red.

‘Richard eats this so easily,’ Okeoma said, seated next to him, watching him.

‘Ha! I didn’t think our pepper was made for your type, Richard!’ Odenigbo said, from the other end of the dining table.

‘Even I can’t take the pepper,’ another guest said, a Ghanaian lecturer in economics whose name Richard always forgot.

‘This is proof that Richard was an African in his past life,’ Miss Adebayo said, before blowing her nose into a napkin.

The guests laughed. Richard laughed too, but not loudly, because there was still too much pepper in his mouth. He leaned back on his seat. ‘It’s fantastic,’ he said. ‘It clears one up.’

‘The finger chops are lovely too, Richard,’ Olanna said. ‘Thank you so much for bringing them.’ She was sitting next to Odenigbo, and she leaned forwards to smile at him.

‘I know those are sausage rolls, but what are these things?’ Odenigbo was poking at the tray Richard brought; Harrison had daintily wrapped everything in silver foil.

‘Stuffed garden eggs, yes?’ Olanna glanced at Richard.

‘Yes. Harrison has all sorts of ideas. He took out the insides and filled them with cheese, I think, and spices.’

‘You know the Europeans took out the insides of an African woman and then stuffed and exhibited her all over Europe?’ Odenigbo asked.

‘Odenigbo, we are eating!’ Miss Adebayo said, although she was stifling laughter.

The other guests laughed. Odenigbo did not. ‘It’s the same principle at play,’ he said. ‘You stuff food, you stuff people. If you don’t like what is inside a particular food, then leave it alone, don’t stuff it with something else. A waste of garden eggs, in my opinion.’

Even Ugwu looked amused as he came into the dining room to clear up. ‘Mr Richard, sah? I put the food in container for you?’

‘No, keep it or throw it away,’ Richard said. He never took any leftover food back; what he took back to Harrison were the compliments from the guests about how pretty everything was, but he did not add that the guests then bypassed his canapés to eat Ugwu’s pepper soup and moi-moi and chicken boiled in bitter herbs.

Everyone was moving to the living room. Soon, Olanna would turn off the light because the fluorescent glare was too bright, and Ugwu would bring more drinks, and they would talk and laugh and listen to music, and the light that spilt in from the corridor would fill the room with shadows. It was his favourite part of their evenings, although he sometimes wondered if Olanna and Odenigbo touched each other in the dimness. He shouldn’t think about them, he knew; it was no business of his. But he did. He noticed the way Odenigbo looked at her in the middle of an argument, not as if he needed her to be on his side, because he didn’t seem ever to need anybody, but simply to know that she was there. He saw, too, how Olanna sometimes blinked at Odenigbo, communicating things he would never know.

Richard placed his glass of beer on a side table and sat next to Miss Adebayo and Okeoma. His peppery tongue still tingled. Olanna got up to change the music. ‘My favourite Rex Lawson first, before some Osadebe,’ she said.

‘He’s a little derivative, isn’t he, Rex Lawson?’ Professor Ezeka asked. ‘Uwaifo and Dairo are better musicians.’

‘All music is derivative, Prof,’ Olanna said, her tone teasing.

‘Rex Lawson is a true Nigerian. He does not cleave to his Kalabari tribe; he sings in all our major languages. That’s original – and certainly reason enough to like him,’ Miss Adebayo said.

‘That’s reason not to like him,’ Odenigbo said. ‘This nationalism that means we should aspire to indifference about our own individual cultures is stupid.’

‘Don’t waste your time asking Odenigbo about High Life. He’s never understood it,’ Olanna said, laughing. ‘He’s a classical music person but loath to admit it in public because it’s such a Western taste.’

‘Music has no borders,’ Professor Ezeka said.

‘But surely it is grounded in culture, and cultures are specific?’ Okeoma asked. ‘Couldn’t Odenigbo then be said to adore the Western culture that produced classical music?’

They all laughed, and Odenigbo looked at Olanna in that way that softened his eyes. Miss Adebayo launched into the French ambassador issue again. She did not think the French should have tested atomic weapons in Algeria, of course, but she did not understand why it mattered enough for Balewa to break off diplomatic relations with France. She sounded puzzled, which was unusual.

‘It’s quite clear Balewa did it because he wants to take away attention from his defence pact with the British,’ Odenigbo said. ‘And he knows that slighting the French will always please his masters the British. He’s their stooge. They put him there, and they tell him what to do, and he does it, Westminster parliament model indeed.’

‘No Westminster model today,’ Dr Patel said. ‘Okeoma promised to read us a poem.’

‘I have told you that Balewa simply did it because he wants the North Africans to like him,’ Professor Ezeka said.

‘North Africans to like him? You think he cares much for other Africans? The white man is the only master Balewa knows,’ Odenigbo said. ‘Didn’t he say that Africans are not ready to rule themselves in Rhodesia? If the British tell him to call himself a castrated monkey, he will.’

‘Oh, rubbish,’ Professor Ezeka said. ‘You are digressing.’

‘You refuse to see things as they truly are!’ Odenigbo shifted on his seat. ‘We are living in a time of great white evil. They are dehumanizing blacks in South Africa and Rhodesia, they fermented what happened in the Congo, they won’t let American blacks vote, they won’t let the Australian Aborigines vote, but the worst of all is what they are doing here. This defence pact is worse than apartheid and segregation, but we don’t realize it. They are controlling us from behind drawn curtains. It is very dangerous!’

Okeoma leaned closer to Richard. ‘These two won’t let me read my poem today.’

‘They’re in fine fighting form,’ Richard said.