По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

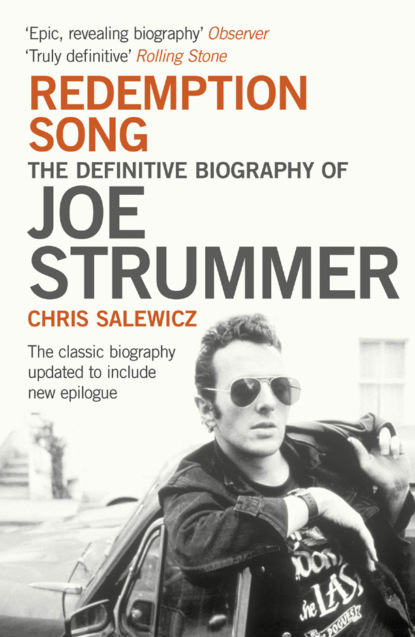

Redemption Song: The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

One by one the houses in Walterton Road were being demolished by the council – it was as though a wartime ghetto was being relentlessly razed. Finally, the only house remaining – everything else around it a state of almost unidentifiable rubble – was 101 Walterton Road, tucked away down at the bottom of the street. Much as there had been problems with the property – the outside toilet, the lack of hot water, the fleas – the house and its inbuilt difficulties had become a defiant energy power-point. Not only had it bonded together a group of musicians and given them somewhere to live and rehearse, it had supplied the name of their group. But the relatively settled existence at 101 Walterton Road was about to end. It too was scheduled for demolition.

By the middle of the summer life at 101 Walterton Road was over. They had found a squat in a house at 36 St Luke’s Road, three streets to the east of Portobello Road, by the West Indian ‘front line’ of All Saints Road.

On 26 July 1975 Melody Maker published a full-length article by Allan Jones about the 101’ers, pushing the group up to a new level. Slanted extremely favourably towards his old friend Joe Strummer and mythologizing their underclass street existence, Jones began, ‘It was some time back in February that I first saw the 101’ers. They had residency in the Charlie Pigdog Club in West London. It was the kind of place which held extraordinary promises of violence. You walked in, took one look around, and wished you were the hell out of there.’

Jones described the mayhem as assorted gypsies and Irishmen knocked seven bells out of each other while the group played their twenty-minute version of Van Morrison’s ‘Gloria’. ‘The band tore on, with Joe Strummer thrashing away at his guitar like there was no tomorrow, completely oblivious of the surrounding carnage. The police finally arrived, flashing blue lights, sirens, the whole works. Strummer battled on. He was finally confronted by the imposing figure of the law, stopped in mid-flight, staggered to a halt and looked up. “Evening, officer,” he said …’

Jones’s article considerably moved on the cause of the 101’ers: it helped the group secure a booking agency, Albion, specializing in alternative pub-rock-type acts; from now on they rarely were stuck for dates to play.

The dateline reads ‘Madrid’. Woody Mellor (as he still is to his old pals) writes to his old friend Paul ‘Pablo Labritain’ Buck:

Dear Pablo,

May the summer be with you. I’m in Espana but it is not green but brown. The food is greasy, good selection of switch-blades. Hopefully will get one for you. How is life and drums? Write me at 36 St Lukes Road, W11. We’re having trouble. Probably get kicked out. Rock’n’roll taking a two week break. You must keep playing: that is the secret. Play for today and play for tomorrow. What this world needs is more rock. Relaxation I cannot find in fact. I’m strung out due to family barny here. Hope to escape to Morocco for a few days, but knowing the diplomatic relations between this country and that I’m not sure that’s true. Love to Roz and your father. I think of green Sussex in this dry land. Must have another Coca Cola. Picking up the lingo a bit. Love Woody. If you get a packet for Peter Treetrunks it’s for you.

What could he possibly have been thinking of sending to Pablo?

‘We hitchhiked to Morocco, with Richard and Esperanza, and rented a place. Joe did bring some hash back,’ said Paloma. ‘In Spain, we stayed at my parents’ house in Malaga for two weeks. “Why are you all fighting?” Joe asked, ‘when everyone was giving their typically noisy opinion in conversation. Joe loved Spain: part of our courting was about the Spanish Civil War. The fight for freedom really interested him.’

When Paloma had spent time with Joe’s parents, she understood his puzzlement over the noise in Malaga: ‘It was stiff, and a little tense, very English. His father drank a lot, his mother read a lot. We’d watch endless TV. I’d go crazy, we’d have two separate beds. With his mum Joe’s kind self would come out more. He loved his mum, who was very reserved.’

Back in London it was a return to the gig circuit. The 101’ers were now a serious working band, averaging four gigs a week. ‘We were now making a bit of money,’ said Clive Timperley. ‘We weren’t too badly off. We managed to buy a van to get to gigs, and we were getting more equipment.’

That things were starting to happen for the 101’ers was a buzz for everyone involved: they all felt it. Vindicated about his belief in himself, Joe began to grow in confidence. As he became Joe Strummer he had discovered a persona into which he could inject all his abilities and fantasies of rock’n’roll mythology, exaggerating aspects of himself, pulling other parts back, adding his own secret ingredient – himself, and that frantically pumping left leg, always a sign that things were about to getabitarockin. In January 1975 the 101’ers had had three live dates, all at the Charlie Pigdog Club. During October it was seventeen. Although the last date at the Chippenham had been on 23 April, the Charlie Pigdog shows were compensated for by the weekly gigs at the Elgin. The line-up had stabilized. At the end of March, Alvaro Pena had quit, Dudanski stepping in. Two months later Simon Cassell had also gone. Jules Yewdall had only lasted a handful of dates, leaving the group in April. Now the 101’ers were a four-piece: Joe Strummer on rhythm guitar and vocals, Clive Timperley on lead guitar, Mole on bass and Richard Dudanski on drums. ‘Strummer wanted to get the band down into a useful working unit,’ said Clive Timperley. ‘We used to say we want the Shadows or Beatles line-up. We used to have these councils of war. Jules went to Germany and came back and wasn’t in the band. There was this joke: “Don’t go on holiday!”’ But Jules Yewdall stayed around, taking photographs and trying to get them dates – he was responsible for the four shows at the St Moritz Club in Wardour Street that began on 18 June. Mickey Foote, who engineered the live sound and acted as unofficial road manager, also pulled in live dates for the group. By now there was a regular posse of fans, almost all of whom were reasonably close friends with the singer with the 101’ers. Among them was Helen Cherry: ‘I went to lots of 101’ers’ gigs, probably nearly every single one. Joe was always very intent on getting more gear, getting more amps, trying to get it all together really. He had a great interest in it. But all blokes are like that around performing bands, aren’t they? Just talking endlessly about the gear. He’d talk a lot about the performances afterwards, being pissed off if something wasn’t right or picking over a gig, picking over certain things that he felt hadn’t come off.

‘I used to find it intriguing when he was going on to a stage in front of lots of people and he’d be worrying about blow-drying a certain pair of trousers with a hairdryer, not worrying about the set-list or the guitar strings. He liked details. I think he had this good detail with people, as well, which is why people were drawn to him as a friend – he could make people feel included.’

After talking to the group following one of the Elgin dates a roadie, John ‘Boogie’ Tiberi, had been taken on: ‘I met Joe, and it was a good vibe: I really liked him immediately – Strummer was always quiet and spontaneous – and I was really impressed with the 101’ers. First time I saw them, I went up to him at the bar and said, “I really like your group.” I started working for them with Micky.’

Pete Silverton, who had hung out with Woody Mellor and Paul Buck at the end of the sixties, was trying to make his mark as a music journalist, writing for Trouser Press, an American fanzine. He went to see the 101’ers play, on 4 August 1975, at the Hope and Anchor on Upper Street in Islington.

It was the first time in around five years that Pete Silverton had seen John Mellor, now in his new incarnation of Joe Strummer. Joe greeted him ‘very warmly. I had the impression that he seemed to feel he was a star – or felt the first step of being a star was to act like a star. He wasn’t an arsehole – and I’ve met lots of those who think they are stars. I felt that Joe was patently using the supposed revolutionary message of squatting, which seemed to be essentially that everybody should smoke inordinate amounts of dope and play rock’n’roll. The political philosophy was at about that level of sophistication.’

Some of Joe’s exuberance of spirit was undoubtedly sparked by the presence of his girlfriend, Paloma. Not that you would have realized they were an item, according to Pete Silverton: ‘Paloma – very sweet, very young, but also very independent for a provincial Spanish girl. They seemed ambivalent together: it was partly the fashion of the time to pretend you weren’t with someone – being in a couple was considered a bit parent-like.’ ‘Joe was madly in love with Paloma,’ confirmed Jill Calvert. ‘But Paloma was having a good and a bad time. Because there was a flightiness to Joe: he wasn’t going to be there for more than five minutes, and you knew that. I never would have wanted to put myself in her position.’

‘The 101’ers were playing at the Hope and Anchor,’ continued Pete Silverton. ‘You would have thought from reading the music press that there was this very big vibe, but there was about fifty people and a dog there – literally, a dog. This was the first time I’d seen them and it was a transcendent moment in my life. I was absolutely blown away. By Joe. Not by the band. They were okay, but Joe … he had this suit on, a big off-pink zoot suit. It looked great. The way it moved, it looked like the sails on a galleon.’

Iain Gillies, Joe’s cousin, told me that the suit ‘came from his father, it was an old post-war suit of Ron’s. Ron thought that it was perplexing and funny that Joe wanted to have it and intended to wear it on stage. He said that Joe had many times previously declared that he’d never wear a suit.’

Pete Silverton resumed: ‘Joe was also wearing co-respondent shoes. He had his hair swept back and he’d got sideburns. His hair’s dark, because he’s greased it, I guess: his natural hair colour is dishwater blond, standard English. It’s the only time I’ve walked into somewhere and gone, “This man is a star!” I remember them playing “Gloria”, with him climbing all over the amps. Joe moved with a strange staccato grace on stage. It wasn’t very big, the Hope and Anchor stage, but he was duck-walking across it. In the music he was playing and in his moves on stage he was obviously stealing a great deal from films of 1950s’ performers. My girlfriend at the time thought Joe was really sexy. I never saw him as a ladies’ man at all but he had a sort of sexy appeal.

‘The songs were also fantastic. It’s nearly all original stuff, but derivative. Joe realized that there were a lot of great songs out there – you could just rewrite them and redo them. By now he had started to be caught up in the thrill of what he was doing, but he was faced with the problem that the 101’ers couldn’t really get anywhere, so there were tensions already in the band. The conflicts in the 101’ers were very clear. Joe is not the most musically literate person in the world. But he had a fantastic rhythmic sense, even though he could barely play the guitar. He was very passionate, but he could get very depressed.’

In October 1975 Jules Yewdall and Mickey Foote had ‘opened’ a new squat at 42 Orsett Terrace, a road of tall, well-appointed terraced houses with stone staircases near Royal Oak tube station. In the basement of the property the 101’ers set up a far more professional rehearsal studio than at Walterton Road. But at Orsett Terrace there were worries about burglaries: the next-door house was occupied by a gang of junkies. ‘Joe hated the idea of junkies,’ recalled Jill Calvert. ‘He thought it was a hopeless existence. I see his own depression as slightly complex, because I think some of the time he was acting: he could act the part of his depressed self. He was also able to escape from it. I know people who are depressed and don’t function. So I would call him a functioning depressive.’

At World’s End, the unfashionable end of the King’s Road, there was some cultural movement. Malcolm McLaren and his wife Vivienne Westwood ran Let It Rock, an arcane boutique, much of whose wares were designed to shock or irritate. McLaren had managed the New York Dolls at the tail-end of their careers; while he had been in the USA, Bernard Rhodes, a friend of his and Vivienne’s, had nurtured another scheme: a group that consisted of the shop’s Saturday boy Glen Matlock and a pair of Shepherds Bush musicians, drummer Paul Cook and guitarist Steve Jones, along with a shortlived character called Wally as vocalist. Since the previous year they had been nagging McLaren for help; all he had provided so far had been a name, the Sex Pistols – after Let It Rock had been renamed Sex.

But in August 1975 Bernard found a scrawny youth from Finsbury Park in north London called John Lydon who walked into Sex wearing a Pink Floyd T-shirt with the words ‘I hate …’ added above the group’s name. Rhodes invited Lydon to come to the nearby Roebuck pub; he auditioned for the Pistols by miming to the pub’s jukebox. ‘Bernie definitely influenced the start of the Pistols,’ Lydon told me in 1980. ‘He got me in the band.’ Bernard Rhodes was adamant that his name was ‘Bernard’ and not ‘Bernie’ – ‘I’m not a taxi-driver.’ Naturally everyone therefore called him ‘Bernie’.

In October 1975 the 101’ers played five times at a former country and western venue called the Nashville Rooms in West Kensington. In the audience one night was Mick Jones and a friend called Tony James. Jones was a guitar-playing art student who had been born in Brixton; after living with his grandmother in a tower block off the Harrow Road, he had moved in 1975 to a small flat in Highgate – though he would soon move back to the tower block. Soaked in pop culture, Mick Jones had felt that it was his destiny to become a rock-’n’roll musician: ‘I’d known since I was ten that this was what I would do with my life. It wasn’t so much ambition as what I knew I had to do.’ But even though he had devoted most of his time on a degree course at Hammersmith Art College to playing the guitar, the fulfilment of his fate had not at first been easy. He’d been in a group called the Delinquents, followed by one called Little Queenie – though he fell out with them. Through Little Queenie he met Tony James, a bass-playing maths student who had placed an advertisement in Melody Maker to form a group. Now Mick Jones and Tony James were trying to start up a group called London SS, one of the great mythological acts of all time, a legend only enhanced by the fact that they never played a single show.

At that 101’ers gig at the Nashville in October 1975 they found that they hated the group, who seemed to this style-obsessed pair to be an archetypal pub-rock outfit. But they were extremely impressed with the singer. At the gig that evening – on which there was clearly a propitious convergence of energies – they ran into a short, bespectacled man with an extremely protuberant nose. This was Bernard Rhodes.

Mick Jones was wearing a pink T-shirt he had bought from Sex that bore the legend ‘You’re gonna wake up one morning and know what side of the bed you’ve been lying on.’ And so was Rhodes. ‘We said, “Go on, stand over there in that T-shirt,”’ remembered James. ‘“Fuck off!” replied Rhodes. “I made it.”’ Impressed, the pair fell into conversation with this gnome-like fellow, who gave them their first information about the Sex Pistols. Mick Jones later said: ‘I thought he looked like a piano player. He seemed like a really bright geezer. We got on like a house on fire.’

For £1,000 Malcolm McLaren had bought a rehearsal studio in Denmark Street, London’s Tin Pan Alley. ‘Mick and I went to see Malcolm at the studio,’ said Tony James. ‘The Pistols were there. We both had really long hair.’ McLaren took them for a meal at which they were both extremely taken with his vision. ‘He told us what would happen,’ remembered James. ‘That a group would come along and completely shake up the music business and alter things utterly. And it all came grizzily true.’

McLaren didn’t recognize the potential talents before him. But Bernard Rhodes had set about looking for a group of his own, after McLaren had turned down his request for a half-share in the Pistols. So the pair arranged a more thorough meeting with Bernie Rhodes, telling him of their plans to form a group called London SS. ‘Bernie made us go up to the Bull and Bush pub in Shepherds Bush to meet him, which was unbelievably rough and dangerous,’ remembered James. ‘As soon as he got there he slapped all this Nazi regalia on the table: “If you’re going to call yourself London SS, you’ll have to deal with this.” We hadn’t thought at all about the Nazi implications. It just seemed like a very anarchic, stylish thing to do,’ admitted James.

Following their meeting with Rhodes, Mick Jones and Tony James placed an advertisement in Melody Maker: ‘Decadent 3rd generation rock and roll – image essential. New York Dolls style.’ Jones was still living in Highgate and it was the phone number of this address that was given in the advert. James lived in Twickenham, at the physically most distant end from Highgate of the 27 bus route: every day he would take the two-hour ride to Jones’s home, where they would both sit anxiously by the phone.

Only half a dozen people replied – one was a singer from Manchester called Steven Morrisey, though nothing came of this. Jones and James were extremely taken with the very first response: Brian James, a guitarist with Belgian group Bastard. As the duo deemed necessary, he was stick-insect thin; after meeting the pair, Brian James went back to Brussels to quit his group.

Beneath a café in Praed Street, Paddington, Bernard Rhodes found the London SS a rehearsal room. ‘When we started working with Bernie, he changed our lives,’ said James. ‘Up to then we were the New York Dolls, and had never thought of writing more than “Personality Crisis”. I remember sitting in the café upstairs with Bernie and saying I had an idea for a song about selling rockets in Selfridges. He liked it. But he was thinking of nuclear rockets and I was only thinking of fireworks. He said, “You’re not going to be able to do anything unless you give me a statement of intent.” It was artspeak. He’d give us reading lists: Proust, books on modern art – it was a great education. He also used to pull a sort of class thing: are you street, or are you middle-class? It didn’t seem very honest, as he was patently obviously middle-class himself.’

Through the door of the rehearsal studio wafted various future members of the cast of punk. One Paul Simonon turned up by accident, and was auditioned for the job of singer: as a perfect David Bowie lookalike he sang Radio One, Radio One, over Jonathan Richman’s ‘Roadrunner’ song, for ten minutes until he was requested to stop. Both Terry Chimes and Nicky ‘Topper’ Headon auditioned as drummers, Headon being offered the job although leaving after a week. ‘I remember the audition was in some tiny little basement studio,’ he told me. ‘I got the gig, but I’d already done an audition for a soul band, and that was fifty quid a week, so I went on the road with them. London SS was very loud rock’n’roll. It was a bad punk group, really. Although the fact that Generation X, the Clash and the Damned came out of it shows there was something there, it wasn’t really very good.’ Having given up the hunt for a singer, London SS started rehearsing with Mick Jones on vocals and a drummer called Roland Hot. Over Christmas of 1975 Brian James left and formed the Damned with other McLaren luminaries Rat Scabies, Dave Vanian and Captain Sensible, leaving the London SS back at square one for Mick Jones and Tony James – although the Sex Pistols had unsuccessfully attempted to contact Jones to offer him the role of second guitarist.

On 18 November 1975 Joe Strummer saw the first of two London shows at the Hammersmith Odeon by Bruce Springsteen. Springsteen, who had never played in London before, was promoting his Born to Run album, his third LP, a landmark record, which saw him touted as ‘the future of rock’n’roll’. ‘When Strummer went to see Springsteen his head was turned,’ said Clive Timperley. ‘The whole idea of Springsteen doing full-on three-hour concerts. Strummer thought, “That’s the way to do it!”’ The fact that Springsteen played a Telecaster was significant for Joe, who saw it as a sign. Joe even bought an excessively long guitar lead, allowing him to wander at will about the stage and even into the audience – just like Springsteen. Clive Timperley recalled that Joe Strummer’s performing histrionics became even more exaggerated; at one gig the guitarist noticed as he launched into a lengthy solo that Joe had disappeared offstage and was lying on an old mattress in the wings; as the moment came for his microphone cue, he sprang up and – as though shot from a cannon – hurtled across the stage, bursting into his vocal lines with perfect split-second timing. Springsteen-like, the 101’ers’ sets got longer: they would often play almost thirty songs, onstage for over ninety minutes, at a time when established high-energy acts like Steve Marriott’s Humble Pie were getting away with thirty-five minutes, including encore.

Joe Strummer’s invigorated stage performance was not all he took from that much-hyped Hammersmith Odeon Springsteen concert. Born to Run, a unique and hugely influential album, was a record that combined an epic rock’n’roll feel with songs that were stories of ‘street life’ in Springsteen’s highly mythologized home town of Asbury Park in New Jersey. The Clash’s similar mythologizing of Notting Hill could be seen as coming partially from here, as well as from the references to Kingston, Jamaica, and specifically Trenchtown, in reggae records, notably those by the newly elected king of the genre, Bob Marley. ‘I was actually turned onto playing reggae by Mole, who was the bass player for the 101’ers, who finally made me really listen to Big Youth and feel it and I sort of saw the light,’ Joe told me. ‘I found it quite hard to step from R’n’B into that deep reggae style. But once it was under your skin it became almost a passion.’ So stirred was Joe by these profound Jamaican rhythms that, on a trip to Warlingham to see his mother and father, he found he couldn’t get the ‘Chh-chh’ sound of the high-hat out of his mind. ‘I went back to London and said, “Give me that record and put it on again.” That’s when we first tried to play reggae, was very early in the 101’ers.’ Although at the Charlie Pigdog Club Mole would occasionally sing a version of ‘Israelites’, the Desmond Dekker classic, Joe recalled the group’s reggae efforts were largely restricted to rehearsals.

As well as the Springsteen dates, there had been another significant show in the London rock’n’roll calendar that November in 1975. On the sixth of the month the Sex Pistols had played their first ever gig at St Martin’s School of Art. Five songs into the set the plug was pulled; among the numbers was a cover of the Small Faces’ ‘Whatcha Gonna Do About It’ in which the singer Johnny Rotten swapped the word ‘hate’ for ‘love’ in the line ‘I want you to know that I love you’. The next day they played at Joe’s alma mater, Central School of Art and Design in Holborn. They got through a thirty-minute set.

The vice-social secretary at Central was Sebastian Conran, son of design guru Terence Conran, who had given him the lease of a substantial house in Albany Street, next to Regent’s Park. One of those he rented rooms to was the new girlfriend of Mickey Foote. ‘As Mickey Foote was a friend of Joe’s,’ Sebastian told me, ‘we had the 101’ers come and play at one of our parties. It was good – I was really into the 101’ers. That was when I first met Joe.’ When the 101’ers played a Christmas concert at Central on 17 December, booked by Sebastian Conran in his capacity as Vice-Social Secretary, he also designed a poster for the show.

Towards the end of 1975, however, Joe Strummer had begun to question the position of Mole within the 101’ers. Dan Kelleher, a guitarist friend of Clive Timperley, had guested with the group since the summer, until on 7 October, when the group played at the Nashville Rooms, he joined the 101’ers as a full member, another guitarist. ‘Once, late at night,’ said Jill Calvert, ‘Joe showed me a drawing he’d done of Mole. Then he said, “I’m gonna sack him.” He was asking, “Is it OK to sack Mole?” I wish I had said, “No, it isn’t. You shouldn’t.” There was a weakness in Joe – and I do regard it as a weakness – that he was pressured by the idea that “Dan can play every Beatles song.” Mole was actually much more musical than Dan, much more inventive: he was totally into reggae. The thing is, he was bald, and he was not pretty. So Joe was saying, “Well, Dan can stand on stage and look like Paul McCartney, and sound like Paul McCartney, and he can hold it all together. Mole stands there and looks odd.” Joe was obviously wanting it to look right onstage. Dan was a friend of Timperley’s and they were sort of “the straights”. But it was Joe and Richard who were really the driving power.’ On 11 January 1976 Mole played his last show with the 101’ers at the Red Cow in Hammersmith. He officially left the group four days later, when Dan Kelleher – renamed ‘Desperate Dan’ – switched from guitar to bass. When I asked Boogie who Joe most related to in the group, he insisted that it was Mole. Such dispensing with people would become a characteristic of the behaviour of Joe Strummer – largely in his career, though also in personal relations. Soon would come the turn of the entire 101’ers to be so especially selected.

Joe Strummer’s life wasn’t all one relentless slog keeping the 101’ers on course. He stayed in touch with his old close friend Paul Buck. ‘Once we had a wonderful Christmas,’ Paul told me. ‘He came down with Paloma over Christmas 1975. He wrote to me, “I’ve met this wonderful Spanish girl and her mum’s coming over for Christmas. Can you tell me of a decent B&B, somewhere around the farm, and we’ll come down there, because it’s nice countryside, and maybe we can meet up for a beer or something.” I said, “Don’t worry about the B&B: just come and stay here.” He turned up, there was him, Paloma, the drummer Richard Dudanski, his girlfriend Esperanza, their mother and some guy called Julio who didn’t speak any English. The whole bunch took over the house. Paloma and her mum were cooking Christmas dinner in the kitchen. My dad came back from the pub completely bemused. I’d forgotten to mention to him that they were coming.’

Joe took other holidays with Paul Buck; together they went to the Norfolk Broads for a few days. On another occasion they hitch-hiked down to Bexhill-on-Sea, where, for the purposes of this trip, the young man originally known as John Mellor was again calling himself ‘Rooney’. ‘It was so cold that we lit a fire on the concrete on the seafront. We were nice and warm and then the bloody thing exploded, because the trapped air got so hot that the fire exploded and threw us over a wall.’

Without Joe being aware of it, though, things were moving around him. ‘We used to go and see the 101’ers a lot,’ Mick Jones said. ‘He was out doing it, and we looked up to that. We never thought we could approach him. We’d looked around and we’d seen every band going, because we needed a singer. But there was a guy there who we knew we wanted more than anyone else. Bernie said, “Let’s ask him.” But we didn’t do it yet.’

While playing at the Elgin in November 1975, the group were approached by Vic Maile, who had produced the first Dr Feelgood album, Down by the Jetty. Maile told the 101’ers he wanted to record them, with an eye to striking a production deal through selling the tapes to a record company. On 28 November the 101’ers drove up with their equipment to Jackson’s Studios in Rickmansworth on the fringe of north London, where Maile – an ex-BBC sound engineer who worked at the studio – recorded six of their songs: ‘Motor Boys Motor’, ‘Silent Telephone’, ‘Letsagetabitarockin’ ’, ‘Hideaway’, ‘Sweety of the St Moritz’ and ‘Steamgauge 99’. The 101’ers claim not to have enjoyed the experience: they didn’t take to Maile’s martinet-like approach to recording. He didn’t get them a deal.

But others were also interested, among them Ted Carroll, who with his partner Roger Armstrong ran a pair of vintage record stalls called Rock On, one in Soho Market, the other in Golborne Road, at the top of Portobello Road, often frequented by Joe Strummer, as well as Paul Simonon. Carroll had decided to start his own independent record label, Chiswick Records. Joe said: ‘When Ted Carroll came to me after a gig at some university and said, “Hey, do you want to make a record then?” it was so far from my mind that anyone could make records who were in our world that I remember looking at him as though I was observing a lunatic, let out from a loony-bin for a day-out trip. I said, “What?” And he said, “Do you want to make a record?” I just couldn’t believe my ears – it was that far away. You know, we were under the sub-sub-sub-level of the subunderground level. It just baffled my head when he said that. I couldn’t believe it.’

But Ted Carroll was completely serious. Two weeks later, on 4 March, the 101’ers were at Pathway Studios in Canonbury, with Roger Armstrong producing. They recorded a trio of songs, ‘Surf City’, ‘Sweet Revenge’ and ‘Keys to Your Heart’. Six days later Joe Strummer, ‘Evil C’ Timperley, Desperate Dan Kelleher and Richard ‘Snakehips’ Dudanski returned to Pathway, where they re-recorded ‘Surf City’ and ‘Sweet Revenge’, and added a version of ‘Rabies (From the Dogs of Love)’. Two weeks later, on 24 and 25 March, ‘Keys to Your Heart’ was mixed and completed.

Under the auspices of Boogie, the 101’ers were in a different studio only three days later, on 28 March. Half a dozen 101’ers’ originals were recorded at the BBC studios in Maida Vale, where live performances were recorded for broadcast. It was not a successful session: ‘Joe didn’t really click with studios at that stage, with the repetitious listening to the stuff that had been recorded, and the laying down of vocals, and the post-production.’ The songs put on tape included another version of ‘Keys to Your Heart’, ‘5 Star Rock and Roll Petrol’ and ‘Surf City’.

Perhaps Joe found the recording experience difficult because he needed the energy of a live performance to overcome his musical limitations, rather than resorting to drugs as did so many of his contemporaries. He and his cohorts were almost entirely outside the grasp of amphetamine sulphate, then widely used on the rock’n’roll circuit. As Joe Strummer told Paolo Hewitt, it was absurd to claim the 101’ers’ shows were the product of this cheap speed: ‘Used to annoy me. At the Western Counties one night we played this really great set, really firing on all cylinders. Then we went out into the bar to have a drink and this bloke goes nudgingly, “Not bad that.” And he’s winking and nudging me and I was going, “What’s the matter with the geezer?” And he says, “How many lines did you snort before that set then?” And we weren’t into speed. We couldn’t afford speed. We couldn’t afford a drink.’

Something needed to change. Gigging on the pub circuit was draining, and Joe grew frustrated. ‘It was just a slog,’ said Joe. ‘It seemed after doing eighteen months of that we were just invisible. I started to lose my mind. I would go around the squat saying, “We’re invisible, we should change our name to the Invisibles.” You’d get back to London about 5 a.m., unload the gear, put on a kettle and go, “What the fuck’s that about?” And in the paper it’d be like Queen and all that. We were just shambling from one gig to the next banging our heads against the wall.’

At least the 101’ers had spent five days of March in recording studios, and they had a full date-sheet of forthcoming gigs. On Friday 2 April 1976, accompanied by Tymon Dogg, the 101’ers played a ‘Benefit Dance’, at fifty pence a ticket, for That Tea Room at Acklam Hall in Notting Hill, beneath the Westway. The mildly psychedelic poster – all blues, greens, and oranges – sets the tone:

Starring That Tea Room Food