По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

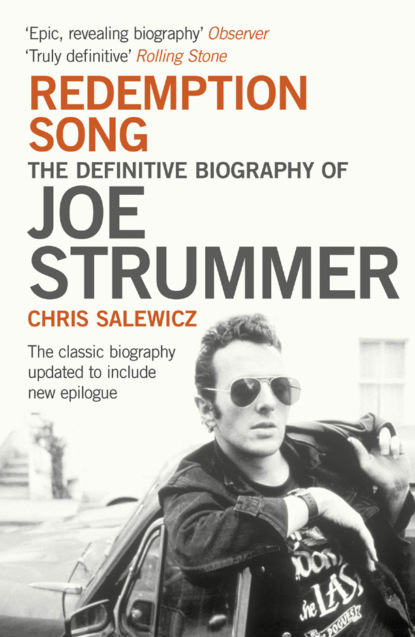

Redemption Song: The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Did Joe take on some of his brother’s distant role when David committed suicide? People with dead siblings frequently assume something of the role of the deceased. So it is almost certain that whoever Joe was before David died, he had a bit of his brother in him after his death; and at the same time, the death of David represented losing a large part of himself.

Moreover, considering the extent to which David Mellor was influenced by the National Front and Nazism, is it any surprise that Joe Strummer should have turned so resolutely against fascism? From the time in 1978 that the Clash appeared at the Rock Against Racism concert in Victoria Park, before an audience of 80,000 people, their front-man was almost indelibly associated with the side of punk rock that had disassociated itself from those flirtations with swastikas espoused by Sid Vicious and Siouxsie. Joe changed that image of punk, becoming rather righteous in his role of tragic, vulnerable spokesman. To what degree, we may ask, was this motivated by his brother’s desperate end?

Although it could hardly compensate for the tragedy Johnny Mellor and his parents had undergone, at least there was some good news that summer.

Although his progress in his Advanced level GCEs had been as stumbling as when he had sat his ‘O’ levels – he had passed Art with an ‘E’ grade, the minimum, been given the consolation prize of a further ‘O’ level pass (one step better than a fail) for the English Literature ‘A’ level paper, and failed History – he had been accepted on the strength of his portfolio for a foundation course at Central School of Art and Design in Southampton Row in central London, by Holborn underground station – a more prestigious school than his original choices, Norwich and Stourbridge. His ambition was still to be a cartoonist, though at school he had declared he wanted to ‘be in advertising’. John Mellor’s course at Central began on 7 September 1970: it was less than six weeks since the sudden death of his brother, and one must presume he was in a state of shock. At the instigation of his grieving parents, anxious their surviving son should have some sort of support system during his further education, he moved into Ralph West hall of residence in Worfield Street by Battersea Park. On his first day at Central college he learned that his place at the art school positioned him as a member of an elite group: there had been over 400 applicants for the sixty places available on the ‘Foundation Year’, which introduced students to the disciplines of art school, preparing them for a degree course at a college of their choice. That Johnny Mellor had succeeded in getting in to Central was a tribute to his talent as an artist.

Having left school, he attempted to metamorphose into some sort of semi-adult new being. Now he announced to everyone he met that his name was ‘Woody’: this was what he was known as at Central – no one called him John or Johnny or even ‘Woolly’, or was confused that he was no longer known as that. Attracted by the cut of his jib, another new student, a girl called Deborah Kartun, overheard him in conversation with a boy who introduced himself as ‘Ollie’. ‘My name’s Woody,’ he said to him. When Deborah started talking to him, he said, ‘My name’s not really Woody: I made it up – but that name Ollie sounded so stupid.’ ‘At Central,’ said Deborah, ‘he was quite extraordinary. It was evident from the first moment I met him there: he was always at the centre of things.’

Johnny’s completed art school application form. (Deborah van der Beek, née Kartun)

On his first day at the art college, in the vast studio room where the ‘fresher’ students collected nervously to meet up, ‘Woody’ Mellor encountered another new student, a girl called Helen Cherry. ‘On the first day we made friends,’ she said. In what would become increasingly typical of him, Johnny was drawn to her because of her eccentric, quirky personality; although her striking prettiness was probably also an attraction: tall and lanky, Helen Cherry would swan through Central in sweeping long dresses. Later that first term John Mellor and Helen Cherry worked together on a cartoon that was published in the college newspaper. Considering what he had so recently endured with David, its theme was telling: ‘It was about this bloke,’ she said, ‘who fell in love with a picture of an air hostess on a poster on the tube. And then in a state of depression he thinks he can find her by jumping on the tube line – and dies.’ Yet at no point during Woody’s time at Central was there any mention of David Mellor, that other depression sufferer, and what had happened to him. Another Foundation student, Celia Pyke, said Woody’s demeanour was such that until I told her about it she had had no knowledge at all of the tragedy: ‘My impression was that he wasn’t somebody who had anything hanging over him. He was so lovely, so funny, so charismatic. A girl I’d met had told me to watch out for him when I got to Central. She said he was one of her best friends – I think she’d been at school with him – and that he was not only a really great person but that he was someone who would do something really great.’ (Later at Central Celia would discover one aspect of Woody’s greatness – that he was ‘a really great snogger’.)

Helen Cherry had been born only days before Woody Mellor, on 10 August. ‘When he first met me and found out that I was born in 1952 that seemed to be a definite advantage to being his friend: “It’s a really special year!” He had funny little phobias about things. Sometimes in a group of people he’d need to pick on somebody: I felt that was a downer side of his character. But he was a very lively, warm person, and really good fun, a laugh a minute. We’d never walk down the street: we’d have to run. He’d say, “We’ll be old when we can’t run down streets. We must run down streets and skip. It’ll be the end of us if we walk.” A very vibrant personality.’

When Iain Gillies came down to London in March 1971 for an interview at art school, he immediately got a sense of his cousin’s life in the hall of residence. ‘He let me – illegally – crash in his room at Ralph West. We collaborated on some artworks in his room. There was paint, glue, cardboard, broken glass and other assorted detritus stuck and smeared over most of the floor. He seemed to approve of this at first but then to my surprise he decided I was making too much mess and he terminated the art projects.’ (Iain was so untidy that he nearly got Joe thrown out of his room.)

‘At Ralph West,’ continued his cousin, ‘he had a picture or two of Jimi Hendrix stuck on his wall, along with the date of Hendrix’s death. He said that Hendrix was his favourite. He also told me that he’d been to the Isle of Wight pop festival. He was very enthusiastic about it and had written out a reminiscence for either a school or college project. He had a few, short, absurdist poems he had written lying around in his room. One poem was called “I’m Going to Getcha”: I’m going to getcha/ You can run into the garage.’

In an evident effort to mark out an identity for himself, Woody would carry a small, battered suitcase with him everywhere that he went; as well as his work materials for the day, it also contained various items of sentimental value: a bus ticket from his favourite bus ride, for example, and the stub from the most enjoyable cigarette he had smoked. But this seems to have been the full extent of any personality that he carried about him. One student, Carol Roundhill, remembered him being dressed in clothes only on the very periphery of fashionability: ‘too short corduroy trousers, a sleeveless knitted pullover, and a short-sleeved shirt and big Kickers shoes. He used to swap things: he had a shirt of mine he used to wear, a little short-sleeved aertex games shirt from my grammar school.’ Helen Cherry found him another second-hand fur coat, of the sort affected by some student boys aspiring vaguely at hipness, a look by now a little out of date. Carol Roundhill’s initial impression of Woody Mellor, in fact, was that ‘he was like a lot of boys: he wasn’t that attractive. He had very dry skin, very curly hair, and dandruff. He struck me as a little lost. It seemed to me sad that someone would move to London and live where he was – although there were a bunch of boys from Central in the same place. He reminded me of one of Peter Pan’s lost boys. The other boys were very focused. Most came from public school and were very self-assured: lots of them knew what they wanted to do before they’d even done the course. But he definitely didn’t. Yet he was really, really friendly. Everybody really loved him. He didn’t have any false exterior and was totally approachable. He wasn’t at all ambitious. I’m amazed he did get it together in the end to work out his talent, because he didn’t seem that bothered at all at art school. He seemed to be in the wrong place.’

Joe Strummer later was characteristically thoroughly dismissive of his time at Central. ‘Well, if you’re in the position I was, there’s only one answer to what you’re going to do after school, and that is art school, the last resort of malingerers and bluffers and people who don’t want to work basically,’ he declared to Mal Peachey, with what you may feel is something akin to false modesty. ‘I applied to join Central Art School, in Southampton Row, and I was amazed when I got in. And then when I turned up I realized that all the lecturers were lechers. All the lecturers were horny, and they had chosen twenty-nine girls and ten blokes to make up the complement of forty [sic]. I just got in there as one of the ten blokes that they needed to make it look not so bad. They had chosen – obviously – twenty-nine of the most attractive applicants from the female sex, and then they spent all year hitting on them. And that was art school.’

‘Maybe it would have been better for him if he’d done fine art, or if he had been able to work out his own ideas,’ considered Carol Roundhill, on the same course. ‘In the graphics studio the work you had to do was very prescriptive, not very creative. It was literally learning how to make letters of the alphabet. It wasn’t his thing.’ This was not what Helen Cherry saw as being the experience of Woody Mellor at Central. ‘A lot of the information about Joe’s life at Central isn’t correct – that he was pushed out of art school, or that he dropped out. He didn’t: he really enjoyed his first year at art college. He liked it!’ ‘He really loved being at Central,’ confirmed Iain Gilles.

The college’s eminences grises seemed not only to like him, but to appreciate his work. One of the tutors at Central was Derek Boshier, a pop artist of considerable renown – he appears, dancing the twist, in Pop Goes the Easel, a Ken Russell documentary about pop art. ‘He was very friendly with the girl students. He used to get off with them, though,’ added Carol Roundhill, ‘not with me.’ You also wonder if he might not have been a model for the type of rock-star artist that Woody became as Joe Strummer, when he was not disinclined to behave in a similar manner. Woody and Derek got on well. ‘Derek Boshier was a very sensitive and intuitive man, and he was very sympathetic and friendly towards Woody, particularly friendly with him,’ said Carol.

Derek was a Trotskyite. ‘I connected with Woody over politics,’ he recalled, indicating that the mood of the times, and perhaps Ron Mellor’s incessant left-wing rants, had finally found a sympathetic home in the soul of Woody Mellor. ‘The atmosphere then was very open to politics. The courses I taught were always mind-opening, not academic. I was into appropriation, a big art movement of the time: for example, I asked my students [a previous one was Caroline Coon, who by now was a doyenne of the hippie underground and ran Release, a charity that provided legal assistance for people who had been busted for drugs] to get hold of a map of the London underground and replace the stations with people’s faces or images that seemed appropriate.

‘When I knew him, he was called Woody. He was a good worker. He had this sort of white man’s Afro haircut, not too long, and was a jeans and sweater sort of person. I was aware that there had been something troubling in his past.’ Derek insists that Woody would often ‘do his own thing’, bringing a guitar with him to art college, no doubt the one he had been given by his cousin the previous year: ‘He’d sit there with a guitar, playing things like “Blowing in the Wind”, during the morning break. He was a huge fan of Bob Dylan. Sometimes it would be hard to get him back to work after that.’

‘Doing his own thing’ included Woody Mellor’s extra-curricular activities while at college, specifically the smoking of joints on the building’s roof. (‘I think he was more into smoking hash than I realized,’ said Carol Roundhill. ‘I used to carry it for him, in case he was stopped and searched.’ Iain Gillies recalled trudging round Surrey lanes near Ron and Anna’s house with Woody: ‘“This must be the definition of impossibility,” he said to me. “Trying to score dope at midnight in Warlingham on Christmas Eve.”’)

Once he absented himself for a couple of days from the college: this followed a visit to the cinema to see the Arthur Penn film Little Big Man, in which Dustin Hoffman plays an ancient Cheyenne Indian, recounting his days of the Old West. The epic film purported to be an accurate portrayal of native American life and was both a commercial and artistic success. It had a deep effect on Woody Mellor. Along with another Central student called Simon Winks, he purloined a set of Helen Cherry’s Caran d’Ache pastels. With them they adorned their faces with Cheyenne-like war-paint markings. So attired, with blankets draped around their shoulders, they went and sat cross-legged on small rugs on the grass opposite the Houses of Parliament. ‘They did that for a couple of days,’ remembered Helen. As the subject-matter of his cartoons clearly demonstrated, Woody Mellor was very taken with the romance of the American West, and especially with the lifestyle of the natives. In 1991, when he stepped in to briefly replace Shane MacGowan as singer with the Pogues, he told me some of his reasons for temporarily joining the Irish group: ‘I like to make instant decisions, and go the whole hog with them. Because when I was young I remember reading about the Cherokees. I read some book about Indians, and one sentence was that when a Cherokee is faced with a decision he always takes the more reckless alternative. That briefly flashed through my mind, and I thought, “Go for it. What’s life for but to make reckless decisions?”’

The rear of an envelope addressed by John Mellor to his schoolfriend Anne Day. (Anne Day)

‘There was always that whole Red Indian, earthy, camping thing he was into,’ considered Helen Cherry, ‘and how that was a more normal way of life, and that we should be living more like Red Indians. There was his admiration for Indian ghost dancing, for instance: if you put this magic vest on, you won’t get shot! He did live life a bit like that.’

For a time Woody Mellor remained in touch with Ken Powell from CLFS. They would meet up in central London and go to pubs or the cinema, often to see art films – Eisenstein’s The Battleship Potemkin was one. Ken Powell was surprised when Woody led him to the Plaza cinema in the Haymarket to see Paint Your Wagon, the comedy Western musical written by Paddy Chayefsky that starred Lee Marvin and Clint Eastwood; Marvin’s performance of the song ‘Wanderin’ Star’ was the final tune played at the funeral of Joe Strummer, thirty-two years later.

Music was not something that Johnny Mellor claimed as a career choice. Carol Roundhill never had any reason to think he might end up as a musician. ‘A writer, or a lyric writer, I thought. I don’t know about the actual music side of it.’ The doodles and sketches he would endlessly come up with she thought to be ‘very Catcher in the Rye stuff, always relating to himself, just quirky, childish, witty, funny stuff. He stood out as being quirky and funny. I think he was very in touch with himself. He didn’t put on any acts or try and impress anyone ever, he just didn’t mind letting it all hang out and revealing himself. That was what was so attractive about him.’

But was Woody already harbouring secret musical ambitions? If he was bringing his guitar with him into class, it would suggest that somewhere within him he had decided on his direction. That Christmas he saw Andy Secombe, who by now was in his last year at CLFS. Andy had become the drummer in a band but had tired of it. ‘I bumped into John, and he said he’d swap the drum kit for something: “What are you into?” I said I was getting interested in photography. He said, “You can have my Minolta SLP camera. I’ll take the drum kit.” So I drove over in my Mini with the drum kit to his parents’ house. But we fumbled and dropped the camera on the concrete outside the house. Miraculously it still worked. But he was deeply embarrassed about it. “Does the camera still work?” he’d ask me every time I saw him.’

The death of David Mellor had distressed Richard Evans, bringing home the pointlessness of the job he’d blundered into. Abruptly one day he quit, ‘and I walk out the door onto this industrial estate, and Joe’s sitting on the wall. He shouldn’t be here: he’s in London, at Central, and he’s sitting on this wall. And I said, “Johnny, what the fuck are you doing?” And he said, “Oh, I came to see you. I thought you were in trouble. Come with me.” Off we went.’ Richard moved into Ralph West, sleeping on the floor for two or three weeks and even joining Johnny Mellor for classes at Central, tucking himself away in the back row.

As the year progressed at Central School of Art, Woody Mellor continued to make his mark. ‘Not in artistic terms,’ said Helen Cherry, ‘not in terms of producing much work, definitely he didn’t. But in terms of personality everybody knew him, though some thought he was an egotist.’ Carol Roundhill added, ‘He was everybody’s friend. I thought I was very close to him, but I went to a Central reunion later, and then a lot of people were claiming to be very close to him.’

Having tired of the constraints of their respective student accommodation, Helen Cherry, Simon Winks, who had sat with Woody as an American Indian opposite the Houses of Parliament, and Eric Drennen, also at Central, did what many students did and rented a cheap property together. A suitable address was found at 18 Ash Grove in Wood Green. Richard Evans took a room. Clive Timperley, a guitarist who had a day-job working for an insurance firm, also moved in.

And there was another lodger. Interlinked with what she perceived as Woody’s indubitable charisma, Deborah Kartun, who had met him on that first day at Central, was impressed that he had spent time in Africa: she thought this to be most sophisticated. For his part, the boy from a bungalow in Upper Warlingham found her background to be equally urbane: educated at King Alfred’s, a progressive co-educational school off Hampstead Heath near her Highgate home, Deborah, blonde, bespectacled and the same height as Woody Mellor, had a Communist father who was foreign editor of The Daily Worker. ‘Woody wanted revolution,’ she said, ‘although that was the mood of the times. It was all very unspecific – none of us were at all politically sophisticated. We were both so naïve.’

In the second term at Central they had begun to become close. ‘It was very gradual,’ she said. ‘I was splitting up with this guy who had been having a nervous breakdown – he helped me through that. At first Woody and I just became friends – he could be good friends with women. I hardly dared think I might go out with him – he was at the centre of everything that was happening. Gradually we got together. At first I’d vaguely gone out with a friend of his, Tim Talent, but that was to get close to Woody.’

When Woody found the house in Ash Grove in Wood Green ‘around April or May of ’71’, Deborah, who had been born a month before him, moved in with him. He told Deborah about what had happened to David: ‘He just said he had trouble communicating, but there was an implication that he might have been gay. Because you’re young you didn’t realise how enormous a thing like the suicide of a family member might be. He was probably still in shock. And his poor parents when we went down to see them that summer of 1971 and had Sunday lunch with them – I had no idea they might be in mourning. There was no alcohol, and it was rather formal, like Sunday lunches were in those days – I was terrified.

‘His mother and father were very sweet. His father was very eccentric – I had the impression he would have been like Woody, if he hadn’t existed in such a conventional, formal occupation. I remember him showing me his tiny vegetable patch, about as big as a table, and his experiments with cross-breeding carrots.’

The extra-curricular activities of the occupants of 18 Ash Grove led to Woody Mellor renaming it ‘Vomit Heights’, although not necessarily because of the effects of alcohol consumed. ‘There wasn’t that much drinking,’ said Helen. ‘A lot of dope, and sometimes some acid.’ ‘It was very suburban,’ remembered Richard. ‘The poor bastard who was the neighbour had these people move in next door which must have been a bloody disaster for him. He was getting all these sleepless nights because these hippies have moved in. We would still be ranting and raving at 3 o’clock in the morning.’

‘At Ash Grove,’ confirmed Deborah Kartun, ‘we were nightmare tenants. We played music loudly until 4am. One morning Woody went out and put all his transistor radios in the garden and started banging dustbins to keep us awake. But we were all too stoned to get out of bed.’

At Ash Grove, said Helen, was when she really got to know Woody Mellor: ‘Joe was like a big mischievous child. He was a great personality to live with, and he used to have a lot of pillow fights with me. We also used to arm-wrestle: even though I was a girl, because I was doing sculpture I could easily push his arm down. I could always win on arms. We had quite a boisterous relationship. But he would never hurt me, it was just very close. There was a lot of hugging, a lot of touching.’

When Woody Mellor mutated into Joe Strummer, this tactile aspect of his personality was always very apparent. In fact, among all of the Clash there seemed to be a ceaseless need to emphasize empathy through physical contact: a flick of the finger on the arm to emphasize a point; a lightly bunched fist to the shoulder to underline the punchline of a joke; a touch to the back of the neck to express sympathy. Did such un-English behaviour extend to Woody’s diet? ‘He did say that his favourite family dish was curry,’ said Helen Cherry. ‘He always went on about his mother’s curry – and it wasn’t that natural for someone like him to really love curry. I felt there had been a certain strictness around Woody that he was always trying to press against and throw out of the window, a bit of a strict household. His father seemed an elderly gentleman, with a very nice posture and white hair – very middle-class.’ I pointed out to Helen that Ron Mellor was then only in his mid-fifties: ‘Really? He seemed to me like a pensioner. I think he was very proud of Woody though.

‘When I went to stay there, his dad said to both of us, what did we want to make of ourselves, and Woody said, “I want to be a rock-’n’roll star.” His dad said, “After one year of art college you want to do this?” He said to me, “What do you want to do?” I said, “I just want to run through long grass.” He said, “That’s not much of an ambition, my lady.” The father didn’t really like these wild things that we said we were going to do with our lives in our late teens: he thought we had our heads right up in the clouds.’ Clearly, Woody Mellor’s expression of an ambition to become ‘a rock’n’roll star’ seems noteworthy. Not only is this the first announcement of any such idea, but he is telling it to his father.

Helen Cherry’s 3D tutor at Central ran an organization called Action Space, a kind of peripatetic playgroup for deprived children which travelled around London. It was, said Helen Cherry, ‘arty sculptural stuff. There was a group of us that went around with inflatables, being stupid and dressing up for children. It was some of the first inflatable work that was done in playgrounds. Our 3D tutor used to use students as cheap assistants. Joe used to sometimes come along.’

At one such event, at West End Green in the hardly deprived area of Hampstead, a game of ‘imaginary cricket’ was organized for the benefit of the children who came along to watch. Essentially this consisted of the Action Space students miming a game of cricket, like the mimed game of tennis in which a group of London students participate at the end of Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-up, a staple work of art-house cinema that was almost a way of thinking about how to live in London. A visitor to this quasi-happening was one Tymon Dogg.

Two years older than Woody Mellor, the Liverpudlian Tymon had been something of a teenage musical prodigy: a multi-instrumentalist, he was already on his way to becoming a masterly violin player. Very shortly he would become considered by Woody as something of an inspirational mentor. He had even had a record released on the Apple label, founded by the Beatles: when he realized that they wanted to market him as a singles artist, Tymon stuck to his principles and walked out on his deal.

Tymon ended up living at 18 Ash Grove. He was making a living of sorts by busking and playing the occasional small gig, and saw Joe’s interest. ‘He would turn up, if I was doing something in some poxy folk gig. There was a crypt in the basement of St Martin’s church in Trafalgar Square where they had folk gigs. I went down there to try out a few new songs. I remember seeing this car coming into Trafalgar Square, and the door opening, and Woody rolling out like a tumbleweed. “Hi Tymon, when are you going on?” Deborah Kartun insisted that 18 Ash Grove ‘was named Vomit Heights after this reggae-like song he and Tymon wrote together that had this line Chuck it in a bucket.’

As the academic year progressed at Central School of Art, Woody Mellor had continued to study, but not enthusiastically. ‘I realized they weren’t teaching us anything,’ he told Mal Peachey. ‘They were teaching us to make arty little marks on paper. They weren’t teaching us to draw an object, they were teaching us how to make a drawing that looked like we knew how to draw the object. And then we got hold of acid, and started to take acid, and then it looked even more transparent. And that was it, really: I had to peel off and it was either work for a living or play music.’

Iain Gillies, who would shortly enter Glasgow School of Art, had noticed that his cousin was already cynical about formal art training by the time he visited him in March 1971. ‘I remember at Ralph West I mentioned the term “negative space”. Woody was scornful of this type of thing. He said, “Huh, that’s the sort of shit they talk about at art college.” I don’t think he liked art being dissected and he didn’t want to know about technique: he just wanted it to flow and be spontaneous. Maybe dope and acid had also increased his disenchantment with institutionalized “art”. Tymon said that Woody had used one of Tymon’s drawings in his end-of-Foundation-Year show at the Central School of Art, a doodle of a horse smoking a cigarette. I think most of Woody’s show was in this vein and the professors didn’t see the joke.’

Richard Evans remembered another aspect of Woody’s end-of-Foundation-Year show: ‘He went into the ladies loos and got all the used Tampaxes for a collage, and that was the last straw. Whether he got kicked out or not I’m not sure. But the essence of Joe was always eight years old.’

To an extent Deborah Kartun had to share him with the other women friends he had during this time, like Helen Cherry – although she insists that theirs was not a sexual relationship: ‘He also had a lot of genuine women friends who he valued. I’ve never had a man be a friend with me the way he was when we were living in Ash Grove – just really there for you. He was quite sympathetic.’

‘I’d done terribly in my foundation year,’ said Deborah Kartun, ‘so I went to Cambridge which did a two-year course, and went into the second foundation year there. It was really old-fashioned, the opposite of Central where everything was conceptual. Woody would come up at weekends or I’d go down to London. We were still very much girlfriend and boyfriend.’

Woody Mellor was secretly distressed that he and Deborah were not together all the time. He wrote to Annie Day: ‘Last time you told me you had had a romance upset but I expect you got over that. Remember: NEVER GET HUNG UP ABOUT ANYTHING!’

‘Woody was a truly exceptional person,’ said Deborah Kartun. ‘He could be very endearing. But he could also be very nasty to people. On the other hand, I could be horrible to him. He announced quite early on that he was going to be a famous pop star. It must have been when I was at Cambridge. He wrote to me on lavatory paper telling me this. But when we were near the end I would be horrible about this: “You’re never going to be a famous pop star. This was because I really thought he couldn’t achieve it. I was disparaging towards him about going down what I thought was the wrong road: I thought he should stick to art. And I was also worried for him: I thought it seemed such a hard life. At the time I think he was briefly working as a dustman.’

‘Woody’ Mellor – as he now was – with Deborah Kartun, his art-school love. (Pablo Labritain)

8

THE BAD SHOPLIFTER GOES GRAVEDIGGING

1971–1974