По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

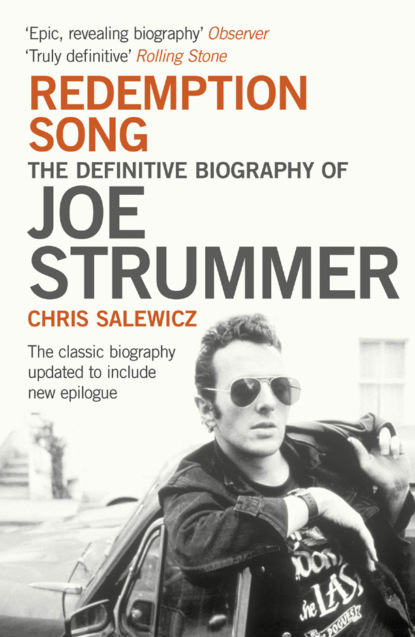

Redemption Song: The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Anna’s engaging and welcoming personality meant that Richard very quickly grew close to her (‘hugely’), and she took on the role of a surrogate aunt. ‘I was closer to her than I was to my own mother, emotionally. It was Anna I spoke to about my issues, my successes and failures. No disrespect to my mum, who was hugely strong in other ways, but it was Anna who was the emotional pillow or rock or whatever. She was tiny, not more than about five feet one, but one of those people who is physically diminutive but whose heart is huge. She was very quiet, and whenever you went there there was always a cup of tea or sandwiches. She’d be fussing around, making you feel comfortable, and would have just made a cake or whatever. She was constantly caring for you. I’m absolutely sure – and it was one of the great joys of Joe – that he had his mother’s huge generosity.’

As he grew into his late teenage years, Johnny Mellor and his father were in increasing conflict, as they played out a classic scenario of a son wanting to escape from his father to find his own course in life. To Iain Gillies Johnny once glumly described Ron Mellor as being like ‘an old bear in a bad mood’. Richard Evans agreed: ‘Like a bear. Sometimes quite angry. You walked around him and weren’t quite sure how it was going to be. If he was purring, it was OK, you could have a really good time with him. But if he was growling you just got the hell out of there. I think Joe and David were wary of him too. There was a weird juxtaposition between the soft, downy-faced mother, with really soft skin, and the dad. I think that’s how they got along.’

As Johnny Mellor grew into Joe Strummer, he displayed considerable behavioural similarities to his father, rendering the earlier conflict between them even more archetypal. ‘Joe and I had this big gap from around the time of the Clash until the last three years of his life, one of about twenty years,’ said Richard. ‘The first thing I noticed when I saw Joe as a grown man was, “Fuck, he’s got his dad’s eyes.” His dad’s eyes were always quite wild and quite irritated-looking, quite red, as though he needed to have an eye-bath. The eyelids were almost separated from the eyeball. Joe’s were the same. It was bizarre, because I looked at Joe as a 47-year-old man, and I went straight back to his dad. His dad was wild-eyed and erratic.

‘Joe’s dad was very critical. God knows why he was in the diplomatic corps. [Joe’s ex-partner, Gaby Salter, says that she once heard a story that Ron was being assessed for suitability as a spy but was prevented from doing so because of Anna’s drinking.] He’d rant about inequality. There’s something in there that didn’t add up – as a child I was wary of him. He was a diplomat, but not diplomatic. He was passionate, full of conviction: he was a socialist. That’s Joe’s political aspect – came from his dad. Somehow that doesn’t fit. If you looked at the man, this was not a sharp-suited, smooth-talking diplomat. He was passionate and volatile. He was also exciting – there was an attraction to the man. You can see what that was for Anna: the international lifestyle, but also that the man was mysterious. It could be beautiful or it could be harmful.

‘There was a huge positiveness about Joe, an energy, that everybody liked. I found myself more and more attracted away from David towards Joe, his younger brother. Being a year younger is an issue as a nine-year-old. But I felt drawn towards Joe, as everybody did. He was just a good person, he had a wonderful capacity to just make you feel better about everything. If he had a good idea – “Let’s do this or that” – somehow he turned it into your idea. He’d be the one saying, “Great idea, I wish I’d thought about that.” You’re going, “Did I think of it? Oh, brilliant.” He had that huge ability to make people feel much better about themselves. It was remarkable: at eight years old he had that. It was nothing to do with the Clash: he just had that gift.’

It was a gift, however, that was about to be sorely tested, at the new school that Ron and Anna Mellor had chosen for their two sons, City of London Freemen’s School in Ashtead in Surrey, 20 miles to the south-west of Upper Warlingham.

The school had been founded in 1854 as the City of London Freemen’s Orphan School. In 1926 the Corporation of London moved the school into the country and it reopened in Ashtead Park in Surrey, a gorgeous estate of 57 acres of landscaped grounds, approached by an avenue of lime trees. You might feel that the idea of being sent to a school established to educate parentless children would have struck a sad chord within Johnny Mellor: he spoke later of how he felt abandoned by Ron and Anna when he was sent to CLFS as a boarding pupil, their solution to the dilemma of how the overseas postings were affecting the boys’ education. After the light discipline at Whyteleafe, CLFS would prove traumatic for both the Mellor boys; Johnny Mellor would never sufficiently come to terms with having been sent away to boarding school by his parents for him to forgive them for the wounding created by this apparent desertion in his childhood. So great had been that hurt that, according to Gaby Salter, Joe’s long-term partner for fifteen years, he was still berating his mother over being sent to CLFS as she lay dying in a cancer hospice twenty-five years later. Part of him felt that his entire life would have been different if he had not been sent there – though that experience was a formative one for the person he was eventually to become.

But naturally Johnny was not showing any indication of such emotion on his first visit to the school. ‘Loudmouth!’ was Paul Buck’s very first impression of John Mellor when he saw him at the entrance examination. Of all the fifty or so boys there, aged between eight and ten, the short-trousered John Mellor – one of the youngest and smallest present – seemed the only candidate unbowed by the exam worries: he didn’t seem to be taking it seriously, laughing and making cracks. ‘I just remember him as being a kid who wasn’t bowed by having to take an exam – which can be daunting for a nine-year-old kid.’

At the beginning of September 1961, dressed in the navy-blue blazers that bore the CLFS coat of arms on the badge pocket, the red-and-blue striped ties of the school neatly knotted at the collars of their white shirts, the regulation blue caps pulled down over their freshly shorn hair, David and Johnny Mellor bade farewell to their parents. Johnny was just nine – because of where his birthday fell he was almost always the youngest in his year – and David ten and a half. Later, in the days of punk, when such a skewed background counted, Joe would claim he had failed the school’s entrance examination and was only accepted because he had a sibling who was already there. This was not true. Because City of London Freemen’s was a public school, however, this led his punk peers to snipe at Joe. Joe never fell back on an easy let-out clause: that his place at the school was a perk of Ron’s job. The Foreign Office paid for David and John Mellor’s school fees, an acknowledgement of the need for some stability in a diplomat’s peripatetic life. (Part of Ron’s employment package was summer-holiday plane tickets to wherever he was stationed; Ron and Anna would add to this themselves with fares paid out for their sons to visit them every Christmas holiday.) There was a number of boys and girls at CLFS whose parents were diplomats or in the military, ten per cent of the school’s 400 pupils. There were many more day-pupils than boarders at CLFS, which added to the boarders’ sense of embattled remoteness; equally unusually for a British boarding school, CLFS was co-educational.

John Mellor in his regulation school uniform. (Pablo Labritain)

Later Joe Strummer recalled his years at CLFS guardedly and defensively, not even mentioning its name until October 1981, when he revealed it in an interview with Paul Rambali in the NME. To Caroline Coon he lied for a Melody Maker article in 1976 that the school had been ‘in Yorkshire’. ‘I went on my ninth birthday’ – in fact it was a couple of weeks after his birthday – ‘into a weird Dickensian Victorian world with sub-corridors under sub-basements, one light bulb every 100 yards, and people coming down ’em beating wooden coat hangers on our heads,’ he told the NME’s Lucy O’Brien in 1986. Paul Buck, who was in the same boarding house as John Mellor, confirmed this. ‘Joe spoke of dark corridors, and basements, and he wasn’t exaggerating. When we started we used to spend most of our time in a dark basement corridor in our boarding house mucking about. There was a recreation room, at the top of the building, very cold and uncomfortable. You didn’t go up there because if the seniors needed to get anybody to do anything they’d go straight there. So we preferred the corridor.’

‘On the first day,’ Joe Strummer said in an interview with Record Mirror in 1977, ‘I was surrounded and taken to the bathroom where I was confronted by a bath full of used toilet paper. I had to either get in or get beaten up. I got beaten up.’ In a Melody Maker article written in 1979 by Chris Bohn, he continued this theme: ‘I was a dwarf when I was younger, grew to my normal size later on. But before then I had to fight my way through school.’

During his first year at CLFS, the nine-year-old Johnny Mellor tried to run away from the school with another boy. ‘We got about five miles before a teacher found us. I remember being taken back to school and the vice-headmaster came out and shouted at us for not wearing our caps. I was thinking, “You idiot. Do you really think we’re going to run away with our caps on?” I just couldn’t believe it.’

Years later Sara Driver, the American film director, told me of how she saw Joe behaving at the end of the 1980s: ‘He was very much wallowing in darkness and talking about growing up and being beaten up at public school when he was a kid and how rough that was.’ As time went by Joe worked out a standard line on his school days: ‘I had to become a bully to survive.’

Paul Buck dismisses this self-assessment: ‘He wasn’t a bully. He was full of life and very funny.’ Nor, he says, was John Mellor a participant in the fights that are often a feature of coexisting adolescent boys. ‘I might have forgotten or maybe I wasn’t there, but it certainly wasn’t “Oh, Mellor’s in a fight again.” No way. He was boisterous but he wasn’t dominant. He was one of us.’

As though making a statement to Ron and Anna, Johnny Mellor refused to participate in school-work for much of his time at CLFS; his mystification at having been taken away from his parents seemed to have created a befuddle of stubbornness that simply did not allow him to find any interest in his studies; he had had an exciting and exotic family life which overnight had stopped: why? Like a punishment, he would never post the letter to his parents that he was compelled to write once a week. The self-confident persona seen by Paul Buck at that entrance exam was a front, something that the quietly sensitive and sometimes easily hurt Johnny Mellor had learnt as a social art on the diplomatic cocktail circuit. When Gaby Salter went through Ron Mellor’s papers at 15 Court Farm Road, she found that almost every year until the Sixth Form the headmaster had written to Johnny’s father, apologizing for the school’s failure to make any headway with his academic progress – he flunked his GCE ‘O’ levels, and had to repeat them.

Although Paul Buck was a year below John Mellor, the boy – who also had an older brother at the school – was to become one of his closest friends, a relationship that continued into the early days of the Clash. ‘He was his best friend,’ the writer Peter Silverton, friends with both of them, confirms of Buck’s relationship to Joe. ‘I saw him and thought, “Oh, I remember you at that entrance exam,”’ said Paul Buck, who formed a double-act with John Mellor, bound together by an absurdist view of life and a common love of music. ‘I remember getting on with him all through school. We were as thick as thieves.’ At first, John would be referred to – as were all junior boys in the school – by his surname, Mellor, frequently contorted into the jokey Mee-lor.

But how did the other Mee-lor boy, whose personality seemed the diametric opposite of his younger brother, fit into this dog-eat-dog world? ‘My brother and I were sent to school,’ Joe Strummer told Mal Peachey for Don Letts’ Westway To The World documentary, ‘and it was a little strange in my case because my brother was very shy. He was the opposite of me – I mean the complete and utter opposite. The running joke in school was that he hadn’t said a word all term – which was more or less true. He was really shy, and I was the opposite, like a big-mouthed ringleader up to no good.

‘I often think about my parents,’ he continued, ‘and how I must have felt about it, because being sent away and seeing them only once a year, it was rather weird. [He misses out the Christmas trips here.] When you’re a child you just deal with what you have to deal with, and it really changed my life because I realized I just had to forget about my parents in order to keep my head above water in this situation. When you’re a kid you go straight to the heart of the matter. There’s no procrastination. I mean, I feel bad now because I was a bad son to them. When they came back to eventually live in England, I’d never go to see them, and I feel bad about that.

‘I would say that going to school in a place like that you became independent. You didn’t expect anybody to do anything for you. And that was a big part of punk: do the damn thing yourself and don’t expect anything from anybody.’

The boy boarders were lodged in four dormitories, according to age. For the younger boys bedtimes were strict: they had to be in bed by 7.30. The seniors did not have an official bedtime. The junior dormitory, where John Mellor first slept, lodged ten boys and two prefects. The dormitory had fifteen-feet-high windows, from which the more adventurous pupils, like Mellor, would climb out onto the building’s flat roof.

Life for CLFS boarders was regimented: day-pupils had to arrive at 8.45 a.m. for assembly, held in the main hall that doubled as diningroom; by then the boarders already had gathered for ‘Boarders’ Assembly’, at which they had to account for what they would do at the end of that day’s lessons, which started at 9.00. Games or homework were all that were on offer. ‘We usually put down games, as this would get us out of the school buildings,’ said Adrian Greaves, who had joined the school the year after Johnny Mellor, also as a boarder. While a ‘Grub’, as Juniors were known, John Mellor wore short trousers for two years and was so diminutive in stature that he was known as ‘little Johnny Mellor’. At first he remained in the fantasy world of small boys in which role-playing games are a norm; in the grounds of the school Adrian Greaves remembered Johnny and himself making ‘tiny villages of mud huts with twig people. He was very normal – bright, enthusiastic and mixed well.’ As a member of the school’s Boy Scout troop, Johnny Mellor learnt to put up a tent and sleep the night outdoors, a skill he would later harness to enhance his love of the festival outdoor life; his woodwork classes had given him the facility to knock up lean-tos and small sheds. Adrian Greaves recalled how even as a ‘Grub’ Johnny would immerse himself in the world of art that had led to the cowboy painting that hung on the wall at Carnmhor: ‘Johnny was very good at drawing. I can remember as early as 1962 him drawing cartoon-strips on long rolls of paper. They were good stories, cowboy and Indian stuff. Certainly I didn’t expect him to be a musician. He would often be in the art-room. I think the art teacher had a lot of time for him.’

In 1962 Ron Mellor had been given another overseas posting, to Tehran, the capital of Persia, a Moslem state ruled in a feudal manner by the king-like Shah, whose family had been installed by American oil interests. Ron and Anna drove down to CLFS and spent a Saturday afternoon with their two sons, explaining where they would be living for the next two years. In the interview he gave to Caroline Coon in November 1976, Joe vented anger at the notion of boarding school: ‘It’s easier, isn’t it? I mean, it gets kids out of the way. And I’m really glad I went, because my dad’s a bastard. I shudder to think what would have happened if I hadn’t gone to boarding school. I only saw him once a year. If I’d seen him all the time, I’d probably have murdered him by now. He was very strict.’

The ‘old bear’ had plenty of spirit, however. He decided that he and Anna would get to Persia by driving, taking the boys with them during the summer holiday. While they were traversing Italy, Anna’s suitcase slipped from where it was strapped to the top of Ron’s Renault: they had to go to a children’s shop to find replacement clothes that would fit her slight stature. In Tehran Ron and Anna lived in an embassy compound. But Anna was not at all taken with the country. ‘She didn’t like Tehran,’ said her sister Jessie. ‘She said she had been spat at in the street. The locals didn’t like her walking out on her own.’ Unfortunately for Anna, Ron was stationed in Tehran for almost four years. During school holidays and even for the half-term break, she would often return to Britain. The next time that David and John went to Persia, they flew. Arriving in a taxi at their parents’ residence, they climbed out of the vehicle to pay their driver, at which point he drove off, stealing their luggage. John Mellor thought this was hilarious, spluttering as he recounted the story back at school.

John (right) and David Mellor (left) share a donkey ride in Tehran with an unknown friend. (Phyllis Netherway)

In 1963 John Mellor and Adrian Greaves appeared together onstage at a school drama evening; previously, John had performed in an ensemble, playing recorder onstage at the age of ten. Inspired by the satire craze of the time, the evening’s performance took current television advertisements and twisted them into skits. A regular appearance during ‘commercial breaks’ was an ad for indigestion tablets called Settlers, which concluded with the catch-line ‘Settlers bring express relief’. Johnny Mellor and Adrian Greaves took to the stage in cowboy outfits as they acted out a scene in which they were part of a wagon-train besieged by Indians. ‘What we need is some settlers,’ said Adrian. ‘Settlers bring express relief,’ Johnny delivered the punchline. At the carol service that Christmas, Johnny and Adrian sang ‘In the Deep Midwinter’ to the tune of ‘Twist and Shout’, a recent hit for The Beatles.

By the autumn of 1963, in the sports’ changing-rooms and in the showers after games, Johnny Mellor, Adrian Greaves and their cohorts would join in off-key spontaneous renditions of a song that had swept the country late that summer, ‘She Loves You’ by the Beatles. ‘We’d all sing along to “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah,”’ remembered Paul Buck. ‘The first record I bought would have been probably “I Want to Hold Your Hand” by the Beatles,’ said Joe Strummer of the follow-up to “She Loves You”. Throughout Britain the image of the Fab Four was ubiquitous by the end of that year; and at CLFS John Mellor’s illustrative skills played a small part. ‘He had a job drawing The Beatles on the covers of everyone’s rough book,’ said Buck. ‘And he’d get the guitars the right way round.’ Plugging earphones into their tinny transistor radios, the boarders would listen in bed to the newest pop sounds on Radio Luxembourg’s evening English service, sailing through the airwaves and clouds of static from the European royal principality; this was especially popular on Thursday nights, to drown out the weekly bell-ringing practice in the nearby church. There was greater listening choice after Easter 1964 and the launch of Radio Caroline, from a converted fishing-boat anchored outside the three-mile limit of the British legal restrictions, pumping out the British ‘Beat Boom’ non-stop; soon Caroline’s 24-hour pop service, a symbol of rebellion for teenagers against the staid BBC, was joined by a flotilla of competitors, including Radio London, Radio City and Swinging Radio England, whose name alone defined the cultural change taking place. On Sunday afternoons the boarders could watch the ATV pop programme Thank Your Lucky Stars, presented by Brian Matthew. ‘That’s the first time I saw the Stones, way down the bill on Thank Your Lucky Stars in the sort of dead-end slot, singing “Come On” by Chuck Berry,’ Joe told Mal Peachey. ‘And we just flipped when we saw it: the whole school was sort of gathered in the day room to watch it and we didn’t need anyone to tell us this was the new thing. We all flipped, and likewise with the Beatles. In fact, I can’t imagine how we would’ve got through being at that school without that explosion going off in London: the Beatles, the Stones, the Yardbirds, the Kinks. Without that rock explosion, I don’t think we would have been able to stand it. It just got us through. Every Friday a new great record. We couldn’t have survived without that music, definitely. We were very young at the time this really happened, and the older boys would bring in the records and on Saturdays they’d let them play them on this huge radiogram that had speakers all over the hall.’

It was not the Beatles or other avatars of the ‘Beat Boom’ who inspired Johnny Mellor to become obsessive about popular music. This came through the California group who became great rivals to the Liverpool quartet, the Beach Boys. ‘Johnny came back to school one term with a copy of a Beach Boys’ Greatest Hits compilation. It knocked him and me out,’ says Paul Buck. John Mellor began to try and grow his hair as long as he could, which was not very long at all, tucking it behind his ears to avoid the attention of teachers.

The boarders’ communal room, a small, badly heated square space intended for the reading of improving books and serious newspapers, also contained a Grundig mono record-player and a large valve radio, both put to purposeful use by Johnny Mellor and his cohorts. Another contemporary, Andy Ward, recalls hearing ‘Little Red Rooster’ by the Rolling Stones blasting out of the window, Johnny Mellor silhouetted in the frame as he mimed exaggeratedly to the Stones’ cover of the blues classic. (‘Johnny Mellor was actually a strong little man, a tough little bugger with a quiet strength,’ he said. ‘He would surprise people, because he was small.’)

In 1988 Joe Strummer told the NME’s Sean O’Hagan that one record had changed his life, the Rolling Stones’ ‘Not Fade Away’, which came out in February 1964, about a year before ‘Little Red Rooster’: “Not Fade Away” sounded like the road to freedom! Seriously. It said, “LIVE! ENJOY LIFE! FUCK CHARTERED ACOUNTANCY!”’ Later he expanded on this: ‘I remember hearing “Not Fade Away” by the Rolling Stones coming out of this huge wooden radio in the day-room. Very loud – they always kept it on very loud. And I remember walking into the room and that’s the moment I thought, “This is something else! This is completely opposite all the other stuff we’re having to suffer here.” It was really a brutal situation. That’s the moment I think I decided here is at least a gap in the clouds, or here’s a light shining. And that’s the moment I think I fell for music. I think I made a subconscious decision to only follow music forever.’

Although Johnny Mellor was a willing participant in the annual school dances, held in the dining-hall, this was the extent of the boy’s musical education: ‘I was non-musical all my childhood. I wasn’t in any choir, didn’t learn any instrument, couldn’t be more completely away from the music. But we were fervent listeners and it was only after I left school that I began to think that I could actually play. I mean, I had a big problem with getting over that, which is why I called myself Joe Strummer. Because I can still only play six strings or none, and not all the fiddly bits. That was part of my make-up, that it was really impossible to play music, and so when I managed to get some chords together I was chuffed. That’s all I ever wanted to do: play chords. Jimi Hendrix said that if you can’t play rhythm guitar you can’t play lead, and I think he’s right, but I haven’t got to the lead guitar playing. But, still, rhythm guitar-playing is an art.’

Anne Day, who was two years below him, insists John Mellor was a member of the fifteen-strong school choir who sang in St Giles church on Sunday mornings – he also seems to forget his ability with the recorder. There were advantages to being a choir member. ‘You had about half an hour’s start on everyone in going over to the church and having a sneaky cigarette if you were in the choir,’ she said.

One abiding memory of life at City of London Freemen’s for Adrian Greaves was the appearance in 1964 of him and John Mellor ‘as woodland sprites in The Merry Wives of Windsor: it was just an excuse to get off school. He was very keen on amateur dramatics. Especially from around fifteen upwards.’ The plays would be staged in the Ashtead Peace Memorial Hall, off Ashtead High Street, and parents would be invited – though Johnny Mellor’s could never attend.

6

BLUE APPLES

1965–1969

When the two Mellor boys went out to Tehran in the summer of 1965, Johnny came across a Chuck Berry EP that included the great American R’n’B performer’s version of a song that he thought was a Beatles’ original on their For Sale album, released the previous Christmas. ‘I remember putting on Chuck Berry’s “Rock’n’Roll Music” and comparing it to the Beatles and being a bit surprised that they hadn’t written it,’ Joe said. Discovering that both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones spoke openly of their allegiance to American R’n’B, Johnny Mellor, who had just turned thirteen, further investigated Berry’s music when he returned to the UK, also discovering the unique shuffling sound of Bo Diddley. He loved these artists.

After a brief stint back in London, in 1966 Ron was promoted to Second Secretary of Information and despatched to Blantyre, Malawi, in southern Africa, where he and Anna would spend the next two years. In Malawi, Johnny discovered the BBC World Service which kept him in touch with the new big releases. He was also very interested in the local Malawian musicians. A stamp in his passport also shows a visit to Rhodesia. ‘Ron and Anna quite liked Malawi,’ said Jessie. ‘But then independence came and they came back to England, pretty much for good. They used to say that Johnny had really liked Malawi. But David found it somehow troubling and unsettling.’

In memories of Johnny Mellor at CLFS an etiolated, almost spectral figure stands off to one side, indistinct, passive and vague. It is David Mellor, Johnny’s older brother. At CLFS the younger Mellor boy spent little time with his elder sibling. Later, according to Gaby Salter, he had regrets over this. But no one really seems to have any sense at all of David Mellor, even those who shared living accommodation with him. ‘Although we were in the same boarding house for two years, we hardly spoke at all,’ admitted David Bardsley. ‘Dave Mellor was very quiet, very shy, very introverted – the complete opposite to John. I suspect David was put upon by the world in general.’ ‘David was in my elder brother’s year,’ Andy Ward told me. ‘He was floppy-fringed and quiet, although he wasn’t someone who was bullied. But no one remembers much about him.’

In the cloistered bowels of the British Museum, where he now works as a clock conserver, Paul Buck produces a photograph of David Mellor; my heart leaps as he hands it to me, as though I have made a great find. But the teenage boy in the photograph seems shrouded in gloom and so indistinct as to be almost transparent; his image is so imprecise that he looks like a ghost, or at least a man who isn’t there. My elation vanishes and instead a chill runs through me. In a set of five photographs of the Mellors at Court Farm Road in 1965, the mystery is repeated: in three of them, taken as the family work in the back garden, David is turned away from the camera – all you see is an anonymous back. In the one picture of the two boys with Anna and Ron, Johnny squats between his parents, while David stands, leaning off to one side of Anna. In the printing process a tiny blue smudge has appeared in his right eye, like a tear, a portent.

‘I do have to agree with what most people say about David Mellor,’ considered Adrian Greaves. ‘I didn’t talk to him much at first. He was a nice chap, but you had to initiate the conversation. He seemed very calm but very shy.’ They both read the works of Cyril Henry Hoskins, who wrote, he claimed, under the direction of the spirit of a deceased lama, Lobsang Rampa: a mishmash of occult, theosophical and meta-physical speculation dressed up in a Tibetan robe, his books read like adventure stories, and enjoyed great popularity during the 1960s. David Mellor devoured them. In 1999 Joe Strummer had mentioned to me his brother’s fondness for bodice-ripper black magic novels like those of Dennis Wheatley. But would he have included Lobsang Rampa among the occult works that fascinated David Mellor in what Joe referred to as ‘a cheap paperback way’?

The interests of the younger Mellor boy were also broadening. When he was fifteen, studying for his ‘O’ level GCEs in the fifth form, John Mellor was a member of the school’s rugby Second XV team, playing in the line, either as a winger or a three-quarter, a reflection of the stamina that he would later show on stage and which was already evident in his ability at cross-country running: he was developing into one of the most accomplished long-distance athletes in the school. Perhaps he should have devoted more time to his studies. When he sat his ‘O’ levels in July 1968, he only passed four subjects, English Literature and History (both of which he scraped with the lowest acceptable grade, a 6, which meant 45 to 50 per cent), Art (one grade higher), and a more respectable grade 3 – 60 to 65 per cent – in English Language; in the November re-sits that year, he added a grade 6 in Economics and Public Affairs, giving him a total of five ‘O’ levels, the minimum requirement for further education.

By the time ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ and ‘Penny Lane’ were released as a double A-side in February 1967, John Mellor’s fondness for the Beatles had evaporated. Now he hungrily devoured both the latest ‘underground rock’ music and its early blues progenitors, much of it from revered DJ John Peel’s late-night Perfumed Garden show on Radio London; every week he read Melody Maker from cover to cover, the former jazz-based music weekly having reinvented itself to find a new readership with long articles about ‘serious’ album artists. Like many other adolescent boys in Britain, he was immersing himself in ‘blues’ music, although – as with most of his contemporaries – at first it was a case of white-men-sing-the-blues: John Mellor incessantly played an iconic LP of the time, John Mayall’s 1966 Blues Breakers album, featuring Britain’s first guitar hero, Eric Clapton. Soon he was seeking out the available American imports by Robert Johnson, the godfather of rural blues, as well as records by the British-based American blues artists Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. He was already in awe of the work of another American expatriate, Jimi Hendrix. When Clapton quit the Mayall group to form Cream with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, John Mellor bought all their releases. Other records became part of his daily diet: the iconoclastic first LP by the Velvet Underground, Blood, Sweat and Tears’ Child is Father to the Man, and, the next year, the first album by Led Zeppelin.

Secreted away in their Surrey school, the boarders were not entirely removed from the modern world. There was, for example, that access to a television set: ‘We got a special dispensation,’ remembered fellow diplomat’s son Ken Powell, ‘to watch The Frost Show when the Stones performed “Sympathy for the Devil”.’ On Saturday evenings they were permitted to watch whichever film – usually a war movie or Western – was being screened. ‘Joe and I were allowed one night to watch Psycho. I can remember being terrified in this cavernous room. I can also recall how I once brought back from Cape Town – where my father had been posted – this shark’s tooth that I would wear around my neck. The next thing I saw he was wearing it. And then I reacquired it. He saw this, and a week later he reacquired it. Then I did. This went on for possibly a year. We never discussed it.’ The shark’s tooth drew attention to Johnny’s own teeth. He refused to ever clean them, or visit a dentist. ‘I’ve decided,’ he announced, ‘to let them fall out, then get false ones. It’ll save time.’

Intriguingly, at this zenith of apartheid, Johnny Mellor never questioned Ken Powell about the political situation in South Africa. ‘We weren’t big into social commentary – it was more girls and music,’ said Adrian Greaves. ‘But Johnny Mellor did have a poster up saying, “I’m Backing out of Britain”.’ This poster, a twist on Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s ‘I’m Backing Britain’ campaign, was fixed to the wall of the study that Greaves by now shared with Mellor and Paul Buck. The psychedelic poster images of the Beatles that formed part of the British packaging of The White Album also adorned the study’s walls after the record’s release in autumn 1968. Whatever his thoughts on the collective output of John Lennon’s group, Johnny Mellor was taken with the man himself, the ‘difficult’ Beatle forever firing off his judgements on injustice or his thoughts on great rock’n’roll, his hip attitudinizing filtered through a patchouli-oil-stained cloak of state-of-the-art psycho-babble. The study’s facilities included a mono record player, ‘a portable plastic thing, with a speaker in the lid,’ recalled Paul Buck, who remembered the affection that he and Mellor had for Elmer Gantry’s Velvet Opera and for Frank Zappa’s protégé Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band, who had been championed by John Peel when his Safe as Milk album was released in 1967. By the time he was in the Sixth Form John Mellor had suffered a personality change, not necessarily for the better. ‘He had become a distinct Dramatic Society arty type, a bit Marlon Brando-like, a sneer to his lip, no respect for convention,’ remembered Adrian Greaves. ‘When he was around eighteen I found him rather obnoxious. He and Paul Buck got on well, because they were both sneerers.’ Greaves remembered Paul Buck and John Mellor falling for an underground myth by drying banana skins over a Bunsen burner before attempting to smoke them in an effort to get high, to no discernible benefit.

In 1968 a brief scandal had billowed through the school when a girl had been expelled for possession of a small lump of hashish. John Mellor became partial to smoking joints whenever he possibly could – he and Ken Powell had got high that year before they went to their first rock concert, the American blues revivalists Canned Heat, at the Fairfield Hall in Croydon, travelling up from the Mellor house just to the south. Richard Evans also remembered going with Johnny Mellor to the same venue to see a show by the group Free.

‘Messing about in the study at school, everything seemed to relate to music,’ said Powell. ‘John would play a game in which he would mime different artists. Two of these I can remember distinctly: he put his hands over his head like an onion-shaped dome, and then he put them out again, as though they were shimmering like water. Who is he referring to? Taj Mahal, of course! Then he mimed some very humble, Uriah Heep-like behaviour, and then tapped his bum – the Humblebums, which was Billy Connolly’s group.’

In the school summer holidays the next year Johnny Mellor, Ken Powell and Paul Buck went to the Jazz and Blues Festival held at Plumpton race track in south-east London, convenient for Upper Warlingham. Among the other Jazz and Blues acts on the bill were those avatars of progressive rock, King Crimson and Yes, and Family, featuring the bleating vocals and manic performance of Roger Chapman, for long a favourite of Johnny Mellor. ‘We slept on the race track in sleeping-bags,’ remembered Ken Powell. ‘The festival ran for three days. We ate lentils from the Hare Krishna tent: we were hardly the types to take food with us.’

That summer was eventful for Johnny Mellor. Richard Evans had long noted Johnny’s skills as a visual artist, endlessly drawing and doodling. ‘He was good, a hugely talented cartoonist. Cartoons were his thing – he had that creativity to do Gerald Scarfe-type satire. Even when very young he had a political awareness in what he was drawing.’ Several of his friends and relatives assumed this was the direction in which Johnny Mellor would pursue a career. Increasingly influenced by pop art and notions of surrealism, as well as by the consumption of cannabis and occasional LSD trips, the youngest Mellor boy would sometimes disappear into creative flights of fancy. One of the most imaginative of these, which created a major furore at 15 Court Farm Road, was when – assisted by Richard Evans – he took a can of blue emulsion paint into the garden and painted all the apples on the trees blue. ‘His father went mad. But we thought it was great. We spent days over this, painting blue emulsion on these apples.’ Before Ron Mellor discovered what his son had done, Johnny took photographs of the trees; later he included them as an example of his work in his application to art school.

By now Richard Evans was known more usually as ‘Dick the Shit’; the sobriquet was not a character assessment – ‘shit’ was a contemporary term used to describe cannabis and marijuana. After taking his O-levels, Dick the Shit had left school, joining a computer company in Croydon. He had just enough money to buy the cheapest available ‘wreck of a car’, a black Austin A40. Wouldn’t it be a good idea to paint the vehicle a more interesting colour? suggested Johnny Mellor. ‘When he said that, I thought of going to the shop and picking out something like metallic silver. But Joe wasn’t having any of that. He was on a different planet.’ Johnny had a better idea: that they use up the rest of the gallon of blue emulsion he had bought to paint the apples; to add some variety he produced more paint, white emulsion this time. ‘We literally just threw this paint over the car. It went rippling down it, in a Gaudi-esque pattern. We painted in the windows like round TV screens. So now I had this blue and white car. Joe signed it, on the front, just above the window-screen.’