По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

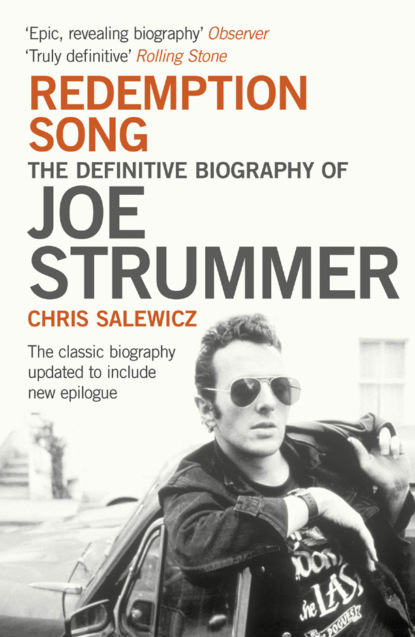

Redemption Song: The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

For travellers heading up the east coast of Scotland, Bonar Bridge, birthplace of Joe’s mother Anna Mackenzie, was the crossing-point over the Kyle of Sutherland – looking at the map it is the last significant indentation on the coastline. Nestling on the north bank of the estuary, the east of the area still hosts the ancient woodland planted by James IV to replace the oak forest that had been decimated in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries by the village’s iron foundry. Five miles from Bonar Bridge is Skibo Castle, the scene in 2000 of the wedding of Madonna to Guy Ritchie; at the handyman shop in Bonar Bridge the stepladders were all sold out, having been bought by paparazzi photographers trying to snap pictures over the wall of the castle. At Spinning Dale, on the edge of Bonar Bridge, the actor James Robertson Justice lived overlooking the water; when Joe’s Aunt Jennie worked for him there was a certain amount of local gossip after he was once alleged to have pinched her on the bottom. Nearby is the battlefield at which the Marquis of Montrose was defeated in 1650, forcing the later Charles II of England to accept the Scots’ demands for Presbyterianism if he was also to be accepted as King of Scotland; the ethos of Presbyterianism runs strongly in Bonar Bridge. A further battle affected Joe’s family history: after Culloden, which marked the defeat of the Jacobite army in 1746, four brothers from the Mackenzie clan hid in this remote corner from the savage reprisals.

When speaking to any of Joe’s Scottish relatives, I sometimes feel I am wandering in a fog of confusion: the same Christian names recur throughout the generations. But to compound my bewilderment the Gillies relatives I met weren’t always related to Joe’s grandmother, Jane Gillies. When Jane moved to Bonar Bridge at the start of the twentieth century, she married David Mackenzie – Jane did not pass on until Joe was fourteen. The Mackenzies form a large extended family. Anna Mackenzie, who was born 13 January 1915 and married Ron Mellor in 1949, was one of nine brothers and sisters. At the wake I spoke to Sheena Yeats, one of Joe’s eighteen cousins: the two women who gave eulogies at the funeral were Maeri, who works for the BBC, and Anna, a teacher, the sister of Iain, Rona and Alasdair Gillies, who were especially close to Joe.

It was amidst the wood-panelled surrounds of Carbisdale Castle that, three weeks before he died, Joe Strummer spent his last night at Bonar Bridge – on 30 November 2002, St Andrew’s Night, at the wedding banquet of cousin George to his partner Fiona. Folded in his pocket Joe had a copy of the family tree that his cousin Anna Gillies had drawn up. From time to time he would put down his ever-present can of cider and pull out the chart as another of his countless relatives hove into view; and he would show his willowy blonde wife Lucinda how this person fitted into his life.

Joe and Lucinda had rented a car at Inverness train station. Disdaining to take the new, faster motorway, he had driven over the highland route of the Struie, which he loved for its wildness and fabulous views of the Dornoch firth, past the inn on the road that is open all night and which serves soup and haggis until seven in the morning. ‘That’s the only way you can come,’ he would say. Arriving in Bonar Bridge that afternoon he and Luce had taken a room at the Dunrobin pub on the high street to rest up: ‘He seemed so healthy, so debonair, relaxed, healthy and fit, and young,’ said Alasdair Gillies, who was five years younger. ‘I remember saying, “You look younger than me.”’ ‘He was in good shape,’ confirmed his aunt Jessie, his mother’s younger sister, and the only surviving female amongst her siblings. Aunt Jenny, who had been married to the late David Mackenzie, one of Joe’s mother’s three younger brothers, thought Joe looked ‘terribly tired’, though she added ‘but they hadn’t eaten and were starving’.

At the wedding party at Carbisdale Castle Joe was fascinated by the traditional Scottish melodies of the Carach Showband, and spent time talking with the piper. At Carbisdale Castle Joe was distressed to find that an LP sleeve of the Bonar Bridge Pipe Band, on which the cover photograph showed the musicians posing outside the castle, contained no record inside it: writing down its details he vowed to trace the LP and get hold of a copy. ‘Unfortunately he didn’t have time,’ said Alasdair.

Fiona, George’s bride, and two of her friends sang unaccompanied versions of Gaelic songs at the party. ‘I looked over at Joe and he was in tears,’ recalled Alasdair. ‘A few minutes later he was saying, “Wouldn’t it be great if you could get twelve of those tunes and put them on a CD.” I was very moved. He said, “You don’t get songs like that now: they last forever.”’ Lucinda had mentioned that in New York on Tartan Day the previous April Joe had insisted on marching all the way up Fifth Avenue, determined to see the pipe bands, and again he had been so moved that tears had run down his face. To the amusement of some of his relatives, Joe and Luce danced their own, not very accurate versions of the Highland ‘Skip the Reel’.

The following day, Joe visited a property called West Airdens, a croft with a startling view that belonged to his aunt Jessie and her shepherd husband Ken, an extraordinary house that seemed magical to Joe. When he learnt that Jessie and her husband Ken had decided it was time to move down to Bonar Bridge, Joe made an instant decision: ‘Let’s buy it now, all of us, all the cousins.’ ‘“For each according to his means,” he said,’ Alasdair remembered, ‘quoting Marx. I said, “What would Engels say?” And he laughed. “What would Jessie say?” I wondered. “She’ll be up for it,” said Joe. Then it was 5 p.m., and he had to go the station.’

Joe was already a day late. He had to be in Rockfield studio in South Wales, where he was to record his next album with The Mescaleros. But he had learnt something that was strongly drawing him back to Bonar Bridge: that day, 1 December, was the birthday of Uncle John Mackenzie, the brother of Anna, his mother, and the man Joe always called ‘the original punk rocker’. As he grew older Joe Strummer felt close to all his Bonar Bridge relatives, but Uncle John held a special meaning for him and touched his heart. Johnny Mellor was even christened after Uncle John. ‘In a perfect world, I wouldn’t go home,’ he stated. ‘Uncle John told me he’s 77 today. In a perfect world I’d go to the Dunrobin for the evening. Maybe I could go back tomorrow.’ ‘He knew he had to go,’ said Alasdair, ‘but didn’t want to. But at the last minute, he said, “I’d better go. In a perfect world, I’d stay. But this is not a perfect world.”’ (When we call round, Uncle John pours us each ‘a wee dram’ of the Irish whiskey that Joe had despatched up to him as a birthday gift as soon as he arrived at Rockfield.)

Minutes into Joe and Luce’s hour-long drive to Inverness station, he phoned Alasdair, fired up with enthusiasm, reminding him they had to buy the house. Moments later he called again, repeating this insistence, and – filled with the emotion of the weekend – reminding his cousin he would waste no time in tracking down the LP by the Bonar Bridge Pipe Band. ‘The Bonar Bridge magnetism holds you: you don’t want to go back to the city. On his last visit Joe exhibited all the symptoms of that condition. Then he phoned me at the station, saying he had made it, and we’d sort out the house. “Love to all,” he said. And that was the last time I saw him. The next thing I knew I got a call from Amanda Temple, the wife of Julien Temple, the film director, who lived near him in Somerset, three weeks later.

‘But those two days we were with him, I felt he’d reached a new level, reconciled both his father’s side and his mother’s Highland stuff. He was being restored to his rightful place in the bosom of the family, onwards and upwards. And it was very hard to bear, when he died.’

Sitting in his favourite armchair by the window of the living-room in the sturdy family croft of Carnmhor in Bonar Bridge, Uncle John speaks with the same lilting Highlands accent that Joe’s mother Anna never lost. ‘Johnny first came here when he was under a year. They were just back from Turkey, and came up by train.’ At one moment on the first of these fortnight-long visits to Bonar Bridge, the toddler Johnny Mellor was found standing at the top of Carnmhor’s steep stairs, shouting in Turkish for someone to carry him down them as there was no banister rail. Upstairs at Carnmhor, the bedroom in which John and his brother David stayed had big brass bedsteads, hard mattresses and bolsters. The two boys were always collectively referred to by the family as David-and-Johnny, like fish’n’chips, or Morecambe-and-Wise, or – perhaps more appositely – like rock’n’roll.

With his young nephew, uncle John Mackenzie shared certain characteristics which only increased as Johnny matured into the figure of Joe Strummer. In his almost Australian aboriginal tendency to go ‘walkabout’, Uncle John predicted behaviour that many people connected with Joe were obliged to accept: the most public example of this was his famous vanishing act in 1982 before a Clash US tour. Uncle John had that same ability to disappear. In the early 1940s, ‘Bonnie John’ – as he was known in his youth – vanished for several weeks. Assuming he was dead, Jane Mackenzie, his mother, went to bed for a fortnight. Eventually he was discovered in Inverness.

After that first visit to Bonar Bridge it was seven years (‘a long while,’ said John, with sadness in his voice) before the Mellor family returned to Anna’s home. On each of the annual visits his family paid to Bonar Bridge between 1960 and 1963, Johnny Mellor liked nothing better than running after Uncle John and his tractor. ‘David was about nine, Johnny was about seven,’ John remembered of that next visit. ‘Johnny was a very cheery, happy boy. He would just wander around the place. He was very fond of being outside. He was a young boy full of life. He did a painting of cowboys and Indians, which we hung up on the wall.’ That painting, a precursor of a theme around which much of Joe’s later drawing and painting was based, hung in the hallway at Carnmhor for many years.

David, Johnny’s older brother, was ‘much quieter’, remembered Uncle John. ‘Johnny used to wander around with me when I was working. I had cattle and sheep: he was always watching them with me. He’d help with what he called the “hoos coo”, milking it. I never saw him play a guitar. I heard his music often. I saw them on the TV as well. They were oot of my mind altogether – the young people liked them.’ But he remembered a surprise phone-call from Joe in Japan in 1982: ‘He was just blathering away. “I’m looking for a job, teaching rock’n’roll,” he said to me, joking of course.

‘He was here for a long while on the Sunday with his wife,’ said Uncle John. ‘He was very reluctant leaving. If anyone had said two words to him he’d have stayed. He said, “I’m bringing my two daughters up in the summertime.” But it never came to pass.’

The visit in the summer of 1960 marked the first time that Alasdair’s brother Iain had met Johnny. From their home in Glasgow, the Gillies family – with Joe’s four cousins Iain, Anna, Alasdair and Rona – had also gone up to Bonar Bridge, as they did every year without fail, and both families were crammed into Carnmhor. With Johnny, Iain would play in the barn, swinging on the rope and rolling on the piles of corn. Together they caught newts from the stream in jam jars, releasing those still left alive. In a pillbox concrete bunker on the farm they discovered left-over boot polish. ‘We probably showed off too much that we thought we were from somewhere else. Johnny seemed to me to be very lively, funny and inventive. David was quiet. I recall Johnny being the organizer and the one who dictated the plans for our games and general mischief-making. He was a bit pugnacious and always insouciant. On the first day we met at the croft, Johnny started a pebble-throwing fight. It was Johnny and David versus me. I was two years younger than Johnny and three younger than David, so I was a bit concerned at first. As the stone-throwing got more vicious I could tell that David’s heart wasn’t really in it, and it tailed off into a draw. Johnny said, “We won that battle, didn’t we, Dave?” In retrospect, I think, to gee David up, give him succour.’ The lines of battle, claimed Anna, were drawn between the Scots and the English. ‘Because I was a girl I wasn’t even recruited for that,’ she complained. ‘In the living room at the farm,’ said Iain, ‘Johnny recited some scurrilous rhyme that he knew, the subject matter of which concerned coating the crack of a female bottom with jam. He knew all the words and to my six-year-old mind it was very funny, slightly shocking, but exhilarating.’ Clearly by that age Johnny was indicating the mischievous humour within him that would remain all his life. But he was also revealing a slight tendency to bully, an aspect of himself that also never entirely went away. ‘On another occasion at Carnmhor,’ Iain recalled, ‘he convinced me that it would be a great idea to completely strip my sister Anna, who was about five, of all her clothes and hide them upstairs in our Uncle John’s cupboard – nobody would ever find them in there, he said. Anna came downstairs and made her grand naked entrance.’

‘I can remember going down the three steps,’ said Anna, ‘where Aunt Anna was drying clothes, and there was a tremendous hullabaloo. They couldn’t find my clothes, which were hidden in Uncle John’s room.’

Each Sunday morning the adults would take themselves and any girls about the house to endure the tedious sermonizing of Mr McDonald at church. On one of these occasions Johnny and Iain, who had quickly become partners-in-crime, decided to provide an entertaining homecoming greeting for Anna. Taking her favourite doll, they suspended it upside down with pegs in the lobby. She was most distressed. ‘It was all blamed on Johnny,’ she said. ‘Because I was a girl they wouldn’t let me play.’ ‘I was immediately aware,’ added Iain, ‘that for all my six years of worldly experience, cousin Johnny was unlike anyone I had met so far.’

It was on one of those trips between 1960 and 1963 that Johnny’s family broke their journey up from London by staying for a couple of days with the Gillies family in Glasgow. David was in a bad mood for the duration of their sojourn because he had to sleep in the same bedroom as Anna. ‘He stood there sawing this piece of string up and down on the door handle, which even at my young age seemed pointless,’ she said. In Bonar Bridge itself, ‘Johnny decided,’ said Iain, ‘that since we were going on a two-mile walk to visit our relatives and the road would take us past a Gypsy encampment, that we would need to be fully armed to repel any attack. Johnny told me to explain the seriousness of the situation to my parents; he would do the same with his, and therefore our parents were bound to provide us with the funds for weapons. There was much adult laughter but they complied, and we bought shiny, one shilling pen-knives at the local newsagent’s. I remember Johnny and I debating whose knife had the most style and panache.’ Johnny and Iain managed to arrive without having to draw their pen-knives.

Anna Mackenzie was born on 13 January 1916, the second child of David and Jane Mackenzie and their first daughter. After attending local schools, she opted for a career in nursing, one of the few choices open for women from families with limited means and one that accorded well with the Presbyterian need to fulfil one’s societal duty. Anna’s older brother, David, had died of peritonitis as a young man. Anna herself was imbued with characteristic Mackenzie qualities: ‘self-reliant, uncomplaining, serene, stoic, ironic, shrewd, determined, engaging, solicitous, and quietly aware of the vicissitudes of life,’ thought Ian Gillies. She was also beautiful.

Moving to Aberdeen, 120 miles south of Bonar Bridge, Anna received her training at Forester Hill hospital. Fifteen years older than her sister Jessie, she was nursing before Jessie had even gone to school. After Aberdeen, Anna went to Stob Hill hospital on the north-east edge of Glasgow, moving into accommodation nearby in Crowhill Road; Anna was promoted to Sister, a position with much responsibility for one still in her early twenties, a clear indication of her abilities.

At Stob Hill she met Adam Girvan, a male nurse from Ayrshire. Twice when she travelled home to Bonar Bridge he was with her. In 1940 they were married.

But as World War II had begun the previous year, Anna Girvan, as she now was, joined the Queen Alexandra Nursing Service; meanwhile, her husband, went into the Royal Army Medical Corps. Although they had expected to do service together, Adam Girvan was sent to Egypt, whilst Anna went to India: it was three years before she saw her husband again.

Stationed at a large army hospital in Lucknow in northern India, this woman from the north of Scotland suffered from the climate. ‘The heat disagreed with her severely,’ said her sister Jessie. ‘She had prickly heat.’ Struck down with appendicitis, which must have triggered memories of the death of her older brother David, she was successfully operated on. Then she was sent to recuperate in the cooler weather higher up in the hills. ‘In the hospital where she stayed she had a great view of the Himalayas.’

There, while lancing a boil for him, she met a lieutenant in an artillery regiment in the Indian army called Ronald Mellor who had been called up into the armed forces in 1942.

Ronald Mellor had been born in Lucknow on 8 December 1916. He was the youngest of four children; Phyllis, Fred and Ouina came before him. His father was Frederick Adolph Mellor, who had married Muriel St Editha Johannes; half-Armenian and half-English, she was a governess to a wealthy Indian family. There was a large population of Armenians in Lucknow. Frederick Adolph Mellor was one of five sons of Frederick William Mellor and Eugenie Daniels, a German Jewess, who had married during the Boer War when his father lived in East Budleigh in Devon. Shortly afterwards they moved to India. The family home in Lucknow was named Jahangirabad Mansion. Later Frederick William Mellor returned to East Budleigh, where he bought a row of cottages that he rented out. His son Bernhardt came to East Budleigh and married the local postmistress. Phyllis, his daughter still lives there.

Muriel Johannes was one of three daughters of Agnes Eleanor Greenway and a Mr Johannes: her two sisters were Dorothy and Marian. After the early death of her Armenian father, Muriel’s mother Agnes remarried, to a Mr Spiers, with whom she had two further daughters, Mary and Maggie.

Frederick Adolph Mellor, Joe’s grandfather, worked in a senior administrative position for the Indian railway, but died of pleurisy in 1919, when Ronald was still a toddler. Following his death his widow married George Chalk, who became Ronald Mellor’s stepfather, but Chalk disappeared to South Africa. Joe’s grandmother Muriel Mellor was not without her problems. A social whirl was part of the colonial norm in India; excessive drinking was an accepted part of that world, and she was an alcoholic, taking out her drunken rages on her children. Gerry King, a former teacher who lives in Brighton, is the daughter of Phyllis, the eldest of Ron’s siblings: ‘I was told that the mother was alcoholic, and used to beat them up. So my mother protected all four of them, and they used to hide from her.’ In 1927 Muriel Mellor died, largely because of her addiction to drink. (In 1999 Joe Strummer told me that both his grandparents on his father’s side had been killed in an Indian railway accident. When I learned what the truth was, I suspected him of some Bob Dylan or Jim Morrison-like obfuscation of his past. But no, said Gaby, the mother of his two children: ‘Joe really thought that was the truth. All the information that came down to him about his father’s life in India was so befuddled, and he was always trying to find out what the real history was.’) Joe’s father Ronald Mellor and his brother and two sisters were then brought up by Agnes Spiers, although Mary, her daughter, took a keen interest in helping to raise the children. ‘Ronald was the favourite with his half-Aunt Mary,’ said Jonathan Macfarland, another cousin on Joe’s father’s side. Ronald and Fred were educated at La Martinière College in Dilkusha Road in Lucknow, a revered Indian school. After La Martinière Ronald Mellor moved on to the University of Lucknow.

After Mrs Adam Girvan met Lieutenant Ronald Mellor, they fell in love. Ron, who by the end of the war had been promoted to Major, was great company, very funny, sensitive, intelligent and articulate; his Indian upbringing and racial mix made him seem unusual to the woman with a pure Highlands bloodline; and when she was with him her natural beauty was only emphasized by the glow of love that surrounded her like a halo. ‘Ron was very exotic, and I can see why Anna was captivated,’ thought Rona, Alasdair Gillies’s twin sister. Anna’s heart was touched by the subtly lingering sense of sadness that Ron had carried with him ever since the death of his difficult mother; some felt that the fact that he couldn’t even remember his father accounted for his faintly other-worldly air of permanent bewilderment.

They decided to make their lives together. But there was a problem: Anna was still married. Divorce in those days was very rare, and not in the vocabulary of the Bonar Bridge Mackenzies. All the same, Anna communicated her intentions to Adam Girvan. When she returned to the United Kingdom at the end of the war, they divorced: Anna discovered that as soon as Adam had learned of her relationship with Ron Mellor, he had cleaned out their joint bank account.

‘I remember my father wasn’t very chuffed about the divorce,’ said her sister Jessie. ‘But Mum didn’t say much.’ But would you have expected her to? As Jessie pointed out, ‘You didn’t even talk about pregnancy. Granny was very, very strict.’ Anna went up to Bonar Bridge and made peace with her parents. In that Highland way of keeping intimate matters close to your chest, the divorce was kept secret from everyone, including her children. ‘My mum told me Anna had been married before, but she never told my dad,’ Rona described a typical piece of Mackenzie behaviour. ‘I wasn’t surprised about it – things happen,’ said Uncle John, customarily phlegmatic. Joe didn’t learn about it until he was in the Clash. ‘I’ve just found out that my mum was married before,’ he said, tickled. ‘She seems to have been a bit of a goer.’

Ron Mellor made his way to London, and took a job in the Foreign Office as a Clerical Officer; considered highly prestigious, the FO only admitted candidates considered high fliers; they were subjected to a supposedly rigorous security check. Soon Ron and Anna were married: in a picture of Ron and Anna on their wedding day on 22 October 1949, her new husband’s caddish Clark Gablethin moustache and double-breasted suit give him the appearance of an archetypal Terry Thomas marriage-wrecker – which, in a way, he was. The newlyweds moved into a top-floor flat, up four flights of stairs, at 22 Sussex Gardens in the seedy area of Paddington. They lived there for two years. Meanwhile, Anna took a post as sister at one of the largest hospitals in London, St George’s by Hyde Park Corner.

Ron travelled to the Foreign Office in Whitehall every day, studying the intricacies of sending and decoding messages which would earn him the job of cypher-clerk, a role whose top-secret nature was only emphasized by the growing Cold War. In the manner of those employed in such positions, he laid down a smokescreen by describing himself to his relatives as ‘third secretary to the third under-secretary’. (Years later, at the beginning of the 1970s, after the Mellor family was once again settled in Britain, Alasdair Gillies remembered his uncle Ron telling him of a visit that Prime Minister Edward Heath made to meet Marshal Tito in the Iron Curtain state of Yugoslavia. ‘Ron was roused out of bed to go with him to send coded messages back to London from the embassy.’)

David Nicholas Mellor was born on 17 March 1951, in Nairobi in Kenya, where Ron Mellor had been posted after marrying Anna. Soon he was given a further overseas posting, to Ankara in Turkey. For unclear reasons, the Mellor family had been in Germany immediately prior to this move to Ankara. Booked on the Orient Express from Paris to Istanbul, they travelled from Germany to the French capital by road. Running late, Ron telephoned ahead: employing diplomatic protocol, he managed to delay the departure of this prestigious train, and Anna told her younger son about running down the platform under the eyes of the waiting passengers.

In Ankara on 21 August 1952 Anna Mellor gave birth to her second son, John Graham Mellor. Brought up with Turkish help around the family home, he learnt a pidgin form of the language. His earliest memory, as he told me, was of the moment his brother leant into his pram, giving him a digestive biscuit.

Ron Mellor’s skills at coding and decoding messages did not go unappreciated by the powers that be. He was transferred to the British embassy in Cairo in Egypt, which was paying close attention to the zealous proclamations of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Egyptian leader, soon to bring about the Suez Crisis with his nationalizing of the vital canal. In this John Le Carré world the Mellor family moved into a house vacated by a certain Donald Maclean and his wife Melinda – Anna complained about Melinda’s terrible taste in curtains and had them replaced. Ron Mellor would regularly have lunch, which invariably consisted of little more than a bottle of vodka, with a close friend of Maclean’s called Kim Philby. These two men, along with Guy Burgess, would defect to the Soviet Union; this trio of intellectuals had been working for Moscow. Interestingly, as the years progressed, Ron Mellor revealed himself more and more to be almost Marxist in political philosophy, an undisguised leaning that might seem surprising for someone working at such a level.

The social whirl of diplomatic functions meant, as it did for many of the embassy staff, that alcohol became a staple part of Ron and Anna Mellor’s diet. Ron was always partial to a gin and tonic, and was fastidious that it was served with a slice of lemon. Anna had a wardrobe of cocktail dresses, and forced herself to learn bridge, which she secretly detested. ‘But that was what you had to do as an embassy wife,’ pointed out Maeri, another of Joe’s Mackenzie cousins. Anna would laugh scathingly to her sisters about a publication called Diplomatic Wives, the in-house magazine of embassy spouses. ‘Anna wouldn’t complain. She wasn’t the complaining type. But I don’t think she liked Cairo,’ said her sister Jessie. As they grew older her two sons David and John learnt to serve drinks and cutely play the parts of junior waiters. A story that attained the status of legend within the Mackenzie family told of how when the boys were taken by Anna Mellor to get a haircut in Cairo, Johnny wriggled so much that the Arab barber became so angry and upset that he stuck his head under a tap to cool down.

In 1956, two months before the invasion of Suez by British and French troops, Ron Mellor was transferred again, to Mexico City. Of all Ron’s overseas postings this was where Anna was happiest; in a photograph of her with her two sons in Mexico City she wears curved Sophia Loren-like sunglasses that emphasize her film-star beauty: she looks impossibly glamorous, rather like the sort of girls you would find backstage at a Clash gig. As though to underline his wife’s sophistication, Ron bought a boat-sized 1948 Cadillac in which to transport his family.

Not long after they had arrived in Mexico City, the area was struck by a devastating series of earthquake tremors. One night while they were having dinner the lights started swinging back and forth; Ron and Anna ran out of the house carrying David and John and sat in the middle of the lawn away from any swaying structures. At first they didn’t notice John when he slipped away. ‘I remember the ’56 earthquake vividly,’ he told me, ‘running to hide behind a brick wall, which was the worst thing to do.’ When the earthquake tremors seemed to have calmed, Anna attempted to bring some calm and normality back into the boys’ lives by bathing them together. Suddenly the water started to slop from side to side as the tremors returned. That night Ron and Anna moved the boys’ beds into their room, so they could all die together.

It was in Mexico City, however, that Ron Mellor developed an ulcer; and he was troubled by the altitude. In 1957 the Mellor family were shipped back to London, and Ron may have had an operation.

5

BE TRUE TO YOUR SCHOOL (LIKE YOU WOULD TO YOUR GIRL)

1957–1964

Before 1957 was over, the Mellor family again was on the move overseas: Ron was posted to work with the British embassy in Bonn, the then capital of West Germany. ‘I was eight when I came back to England, after Germany,’ Joe Strummer told me, forty years later. ‘Germany was frightening, man: it was only ten years after the war, and what do you think the young kids were doing? They were still fighting the Germans, obviously. We lived in Bonn on a housing estate filled with foreign legation families. The German youth knew there was a bunch of foreigners there, and it was kind of terrifying. We’d been told by the other kids that if Germans saw us they would beat us up. So be on your toes. And we were dead young.’

Aware of the need for some kind of stability in the lives of his family members, Ron Mellor decided that he must establish a permanent home in England, his adopted country; his sons lost a new circle of friends with every overseas move. One consequence of this seemed to be Johnny’s almost acute sense of self-reliance and self-awareness. But for David, Ron and Anna’s eldest son, the constant break-up of friendships, accompanied by that nagging wonder of whether everyone would always disappear from his life with such sudden ease, seemed to be having a negative effect: increasingly quiet, he often seemed lost in thought. This struck a nerve with Ron: his memories of his own traumatic childhood would rise when confronted by the hushed sense of ‘otherness’ that floated about David. In turn it was hard for sensitive David to be unaffected by the way this unhappy childhood was so deeply etched in his father’s being; it was as though they were cross-infecting each other with indeterminate but undeniable suffering. Yet David showed no evidence of Ron Mellor’s tendency towards volatile mood swings. ‘Ron loved being able to just reminisce,’ said Gerry King, Joe’s paternal cousin, remembering her visits to the Mellors. ‘But he would go into moroseness. I felt it once or twice – some pity. I think he’d had such a sad life, really.’

Ron Mellor’s plan to buy a house in London hit a problem: he had no savings, so where could he raise the money for a deposit on a property? There was a potential solution. In India he had always been the favourite of his half-aunt Mary, who had married a rich Pakistani man by the name of Shujath Rizvi, and had no children of her own. (The somewhat formidable Mary Rizvi lived in a state of pasha-like splendour, with one room in her palatial home reserved simply for her Pekinese dogs.) Ron mustered up his courage and wrote a letter to his half-aunt: could he borrow £600 for the deposit on a house? Aunt Mary immediately gave him the money. Back in London in 1959 for what he knew would be a three-year stint in Whitehall, Ron Mellor made a down-payment on a three-bedroomed single-storey house just outside Croydon in the south-east of London. The property, at 15 Court Farm Road in Upper Warlingham in Surrey, was being sold for £3,500, cheap even by property prices of the day, a reflection of its dolls-house size. A cul-de-sac, Court Farm Road wound round the side of a steep hill that formed one side of a valley that sloped down to the main Godstone Road. Located on a corner of Court Farm Road, No.15 was the last of four identical bungalows, built in the 1930s and – partially due to their hillside perch – having something of the appearance of Swiss mountain chalets, a look that distinguished them all the more from the larger detached and semi-detached houses that made up the rest of the street.

When the Mellor family moved into the bungalow, David and Johnny were sent to the local state primary school in nearby Whyteleafe. Joe Strummer would later seem to dismiss the home bought by his father as ‘a bungalow in south Croydon’. But this is exactly what it was; for once he was not disguising his past. Presumably dictated to by the maxim that location is everything, Ron Mellor had bought what was essentially a miniature version of the adjacent properties in the neighbourhood. In fact, it was typical of English houses built in the 1930s, and – as did much of Britain at the beginning of the 1960s – it still had much flavour from that decade. Through the black-and-white front door was a hallway-like corridor: to the left was Ron and Anna’s bedroom. Opposite, on the right-hand side, was a small kitchen whose window faced the road; further along on the left was David’s bedroom and the bathroom; and on the right was the sitting room and Johnny’s small bedroom. ‘They never spent a lot of time worrying about pretty carpets or furniture. It was just kind of bricks and mortar and that’s where they were,’ said a visitor. On display at 15 Court Farm Road were exotic artefacts gathered at Ron’s various international ports of call: bongo drums, a wooden framed camel’s saddle, pouffes made of Persian leather. Although a television did not appear at first, there was a large radiogram of the type later featured on the sleeve of the ‘London Calling’ single. ‘My parents weren’t musical at all,’ Joe later told Mal Peachy. ‘They had sort of Can-Can records, from the Folies Bergère, and that was about it. Maybe a few show tunes like “Oklahoma”, that sort of thing. I remember hearing Children’s Favourites [a request show broadcast at nine o’clock every Saturday morning] on the BBC, things like “Sixteen Tons” by Tennessee Ernie Ford.’

Visitors would sometimes feel the house seemed run down – the diplomat and his wife, after all, had been used to servants and had lost the habit of home maintenance. Some improvements were made. French windows were installed, letting in far more light and a view of the disproportionately large garden and lovely apple orchard. The patio that separated the living-room and garden was extended. But little else was done to the home that would serve the Mellors for over two decades. Although slightly shabby, 15 Court Farm Road was an extremely comfortable house. But the sense of alienation in the area was reflected inside it. ‘I think Ron and Anna lived this very weird, isolated life,’ Gerry King remembered of a visit there in the late 1960s. ‘You could imagine them in the times of the Raj, as though he had been posted to some obscure place in India, and they are there, sipping their sherry, and going on to whisky. That sort of thing: a feeling of not being real. But there was something very wonderful and lovely about them both. And Uncle Ron also had that gentleness. I felt that he didn’t cope with reality well. But he was a lovely man.’ Yet Ron and Anna’s loneliness was not surprising: like their sons, Ron and Anna had suffered disappearing diplomatic service relationships, and had few friends in London.

Living at 54 Oakley Road, some 500 yards from 15 Court Farm Road, was the Evans family. Richard, the youngest child, was a few months younger than David Mellor and a year older than Johnny Mellor. Soon after the Mellor family had moved into their new home, the Evans and Mellors met up – he too attended Whyteleafe primary school. ‘It’s just a village primary at the bottom of the hill. That’s where I went. That must’ve been where we met.’ The two families became close; Richard quickly came to regard David Mellor as his best friend. ‘It was Johnny-and-David, a kind of Scottish thing. “Johnny” – that’s what his mother always called him. David is nine, I’m nine. He’s very quiet, very withdrawn, but there’s something very comfortable about being with him. And I would literally sit there with him not saying anything for half an hour and it was OK, you didn’t have to. He was my mate, my best mate. But all three of us played together.’

Hardly a day would go by when Richard Evans was not over at the Mellor house: ‘My recollection of it was that I was always there and it was always a very warm house. They never locked it up. The door was always open. My parents were really security conscious: our house had been burgled. But Anna was not, the house was always open, they never locked the door. Yet they never got turned over. Maybe it was just the atmosphere of the place. But it was always an open house.’