По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

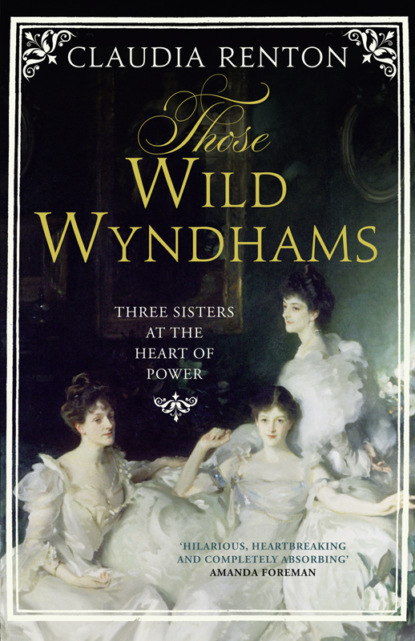

Those Wild Wyndhams: Three Sisters at the Heart of Power

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

As the troops prepared to leave, the Wemysses travelled south, and the Wyndhams congregated first at Wilbury and then in London. Only Mary was absent, forbidden by both families from making the long journey while she was still frail. She remained with Mrs Sayers and Ego, reliant upon her family’s letters for updates. They were not encouraging. ‘Tonight is the awful night when we say goodbye I never felt such a horrible feeling as it is – Poor darling Rat [Madeline Wyndham] looks so unhappy but she bares [sic] it wonderfully,’ Mananai told Mary on the eve of George’s departure after a day spent watching the inspection of the troops at Wellington Barracks.

The next day they were at the Barracks again, among the cheering crowds waving off the troops in the glittering sunshine of an early-spring day, determined – said Madeline – to show George ‘no signs … of our sorrow but rejoice in his joy’.

Madeline left London for Gosford. The visit was intended to raise her own spirits as much as her daughter’s, but seems rather to have made them confidantes in each other’s misery. She then returned to Wilbury ‘with a distracted mind & a sad heart & eyes that have gone blind with much crying these last weeks’.

The house was in a state of upheaval. Final preparations were being made for the move to Clouds, which was to take place while the Wyndhams were in London for the Season. ‘The packing that is going on here is terrific. 3 immense waggons came here the other day and were loaded I don’t know how high & then trudged off at six o’clock in the morning,’ Pamela reported to Mary.

On finding that her pet white sparrows had been left unfed and allowed to die in the chaos, Madeline saw another augury of George’s fate.

It was not long before her mind would find another avenue along which to race.

In April 1885 the Gang rejoiced at the engagement of Alfred Lyttelton to Laura Tennant, two of the most beloved of their group. All who knew Laura praised her to the point of hyperbole. She was possessed of ‘an extra dose of life, which caused a kind of electricity to flash about her … lighting up all with whom she came into contact’, said Adolphus (‘Doll’) Liddell, one of the many men in love with her.

Laura was intensely spiritual, very flirtatious and extremely frank. Mary considered her to be her closest friend. The two concocted grand plans for a literary salon. Shortly after the engagement the Elchos jaunted to Paris with Arthur Balfour, Godfrey Webb and Alfred Lyttelton to visit Laura, who was with Margot and Lady Tennant shopping for her trousseau. ‘We form a fine representative party of Englishmen a married couple, an engaged couple, “doux garcons” as Webber wd call it in his fine English accent … & Margot does well for a sporting “mees”,’ Mary told Percy.

In old age Mary recalled the irrepressible Tennant sisters’ debut in London as causing ‘a stir indeed – one may almost call it a Revolution … theirs was a plunge, a splash as of a bright pebble being thrown from an immense height into a quiet pool … Many were startled and most were delighted.’

The Tennant girls, unchaperoned by their mother, were ‘of totally unconventional manners with no code of behaviour except their own good hearts’, as the wife of Arthur’s brother Eustace, Lady Frances Balfour, put it.

At Glen House, the family home in the Scottish Borders, they entertained male guests in their nightgowns in their bedroom, arguing late into the night over philosophy, spirituality, politics and psychology. The room was known as the ‘Doo-Cot’ (Dovecot) in ironic reference to their heated debates. In London – and in qualification of Mary’s recollection – it took them some time to achieve entrée. Laura met Lady Wemyss – who lived not thirty miles from Glen at Gosford – only when she married Alfred.

Alfred’s brother Spencer described the Tennants to his cousin Mary Gladstone as a family of ‘brilliant young ladies and vulgar parents’.

Mary Elcho, of somewhat unconventional behaviour herself, was captivated from the first.

Mary recounted this week in Paris to her parents in exhaustive, delighted detail. She told them about afternoons dozing on the sofa while Laura played the piano in their little shared sitting room; about their proficiency at lawn tennis that had roused the natives to applause; about their conversation, ‘as animated as the most spirited of Frogs’. Mary complained to Percy about the stolid Lady Tennant: ‘someone always has to lag & try to talk to her & she talks not at all! Except in the most commonplace manner.’ She told them about drives in the Bois de Boulogne, delicious déjeuners and dinners at the Lion d’Or. They went to the Théâtre du Palais-Royal and then, Mary added in strangely bathetic phrase, they ‘walked home afterwards’.

She did not tell her parents that the person with whom she had walked arm in arm, deep in conversation, on the winding route home was not Hugo but Arthur.

On their return to London Arthur dined with the Elchos. Mary was wearing a low-cut gown which startled her guest into an unexpected compliment. ‘You have a jolly throat,’ he told her, such an effusive comment for the reserved Arthur that Mary openly blushed.

One of the Gang’s defining characteristics, stemming directly from the nightgowned Tennant girls entertaining in the Doo-Cot, was their belief that men and women could be intellectual equals, and capable of intimate friendship on the mental plane. They chided scurrilous-minded outsiders, unaccustomed to seeing one man’s wife deep in conversation with another woman’s husband, for suspecting more earthly inclinations. Among themselves they conceded a little more. Mary described herself to Hugo as a ‘little flirt …!’

but all maintained that this flirtation was innocent. Throughout the early years of their marriage, the Elchos conducted a double romance with the Ribblesdales. The two couples holidayed together in Felixstowe and the New Forest, splitting off into contented pairs: Hugo and Charty, Mary and Tommy. It was convenient, diverting and fundamentally harmless. As Mary explained, ‘Migs in practice (flirtation practice) dwells on the ambiguity of implications the possibility of a backdoor or loophole that Tommy considers the word to contain. Migs thinks it doesn’t matter what she says in her letters to men conks [admirers], provided she only implies it … for if brought to book she can say that they have misunderstood her – and nice men conks never take one to task.’

In essence, it was courtly love, updated: men pursued, women teased, both remained beyond reproach.

Yet Mary and Arthur’s relationship was different. ‘She reverences him,’ said Laura. Worryingly for Laura, upon broaching the issue with Arthur it seemed that he was not ‘as indifferent heart-wards to her as I at first thought – he said several things about it that gave me qualms’. Mary and Arthur’s obvious mutual attraction was not beclouded by the bavardage of ‘flirtation practice’. Within the context of Society this was dangerous: ‘the eyesight of the world … is vastly farsighted & sees things in embryo’, Laura warned Mary.

The gossips of the New Club, seeing Mary and Laura dining with Arthur alone, could cause havoc.

Laura was not the only person warning Mary that summer. Shortly after the Elchos had returned from Paris, Madeline Wyndham visited Stanway and had several lengthy private talks with Mary, undoubtedly about Arthur. Afterwards, Mary wrote to thank her: ‘I can’t say what it was having you here & what it is to have you at all. You are the best influence in my life & stronger than myself … as noble healthy & cleansing as a gust of … mountain air removing cobwebs from one[’s] moral mirror.’

But, despite these protestations, her behaviour did not alter at all.

Mary had boasted that her mother, in the years before her marriage, had never quite been able to ‘fathom’ her. Now, it seemed no one could. Laura, analysing the situation, could only conclude that Mary, in the grip of fascination, neither knew herself nor could help herself, and that moreover infatuation blended with ambition: for ‘her affection for Hugo is strangely mixed up with her affection for the man she knows can, will & does help Hugo more than anyone else does’. For Laura, Mary was a woman buffeted by her emotions, and only Laura’s firm hand might prevent Mary from sleepwalking into disaster. ‘I never allow for a minute when I am with Mary that she is in love with A … were I to say “you are in love” she would believe me and poking the fire is productive of flame; & at present the conflagration is chiefly smoke,’ she told Frances Balfour, further placing the onus upon Arthur, as one capable of controlling his feelings, to put a stop to things.

A letter written by Mary to her mother that summer suggests otherwise. Madeline Wyndham’s anxiety had been exacerbated, rather than eased, by her visit to Stanway. Shortly after leaving Mary, and while visiting her friend Georgie Sumner, she sent Mary a frantic letter. She did not directly mention the subject. Instead over numerous pages of increasingly illegible scrawl she dwelt long on the cautionary tale of Georgie, estranged from her husband, suffering ‘deadly remorse’, feeling she had ‘sinned against God & Man … and would die … sooner than act again as she did …’.

‘I thought perhaps you might send me a wopper,’ Mary replied, treating her mother to a lengthy, strangely abstract discourse on the nature of wrongdoing. It is a tortuous read, but in short it divides the world into two classes: wrongdoers too stupid or wicked to know they did wrong; and those who knew, but did it anyway, preferring to face the consequences at a later date. Mary classed herself in the latter camp. The only remedy she saw was to ‘pray … to set one’s heart & to keep it fixed in the right direction & day by day the effort will become less … the backsliding & driftings less frequent – to be able to make one’s will want to do the right thing’.

Taken out of the abstract it is a startling admission. Mary’s heart was not fixed in the right direction. She wanted to be with Arthur.

The following year, the Elchos and Arthur went on a walking tour of North Berwick. Printed backwards in tiny letters in Mary’s sketchbook from the trip are the words: ‘How I wish I could, but you know that would be impossible.’ It has been suggested that the ‘impossible’ thing was divorce, although it might have been sex, or even something more innocent.

It is startling to think that Mary could ever truly have contemplated divorce – which would have made her a social pariah, would have given Hugo custody of her children and would have destroyed Arthur’s political career. More likely, Mary simply chose not to think of the consequences at all. As Laura later said, it was a case in which ‘they hurt other people because they liked themselves too much …’.

But, for whatever reason, Mary faltered. After Madeline had failed to acknowledge her daughter’s easily decipherable code in the summer of 1885, Mary no longer attempted to confide in her. In fact, she seems almost to have stopped communicating at all.

Desperate and panicked, Madeline Wyndham increased the barrage, while still maintaining that nothing was wrong. In frenzied underlinings from Hyères, as Mary’s birthday approached, she exhorted the Elchos to ‘Cling on to doing things together … come nearer to each other … you must both work together … don’t get separated in your lives.’

On the Elchos’ wedding anniversary, invoking the memory of the ‘good Dear good single-minded Child’ Mary had been two years before, she demanded that ‘Hugo … keep you from all pitch … I know he first loved you for all that & Married You to have a Wife different from all the world. I’m sick of some of the Wives I see … I love you. I believe in you. I worship you.’

Mary broke her silence with cheerful obfuscation and a generous approach to the truth. ‘Hugo read … the birthday exhortation & wondered whether you thought I didn’t care for him any more!’ she said, ‘but I told him yr words were as warnings not as remedies … I don’t think two people could easily be more united than we are & will always strive to be … I would rather kill myself than make you miserable & disappointed in me.’

Mary fell pregnant shortly afterwards (her second son, Guy Lawrence, was born on 23 May 1886). Yet the fact of her pregnancy was not enough to calm a ‘wretched’ Annie Wemyss, who had also heard the rumours, and that autumn recruited Laura to keep Mary and Arthur apart. Laura enlisted Frances Balfour. The two conspired to prevent Arthur from going to Stanway in December, for the house party which was fast becoming an annual tradition, ditching it themselves in order to keep him away: ‘v [sic] good of us I think!’ said Laura, who used her own six-months’ pregnancy as an excuse.

In the early months of the new year Laura trailed Mary like a shadow: almost every engagement with Arthur set down by Mary in her diary, whether visiting Sir John Millais’ new gallery or drinking hot chocolate at Charbonnel et Walker in the West End, notes Laura gently, inexorably interposing herself between the two, trying with all her might to reduce their relationship to innocent friendship.

SIX (#ulink_9f1efebf-0dec-5c60-8522-7bce98e83a2a)

Clouds (#ulink_9f1efebf-0dec-5c60-8522-7bce98e83a2a)

As soon as the Stanway party ended, Mary left to join her family for their first Christmas at Clouds. The Wyndhams had finally moved in in September 1885. Throughout the autumn her excited younger sisters had bombarded her with letters giving her every detail of their ‘scrumtious [sic]’ new domain.

If Mary was disappointed by Arthur’s previous absence, she showed no signs of this to her family. She arrived at Clouds, loaded down with ‘millions of packages’, Ego, his nurse Wilkes (known as ‘Wilkie’), her poodle Stella and a cageful of canaries, and was rushed around the house by her sisters demanding to know if it was exactly as she had imagined. All Mary could manage was ‘delightful’.

The house was enormous. Built of green sandstone with a red-brick top floor, it looked like a storybook house that, like Alice, had found a cake saying ‘eat me’ and mushroomed to a hundred times its normal size. ‘I … keep discovering new rooms inside and windows outside,’ marvelled Georgie Burne-Jones on her first visit in November.

Half a century later, an estate agent’s particulars listed five principal reception rooms, a billiard room, thirteen principal bedrooms and dressing rooms, a nursery suite of two bedrooms, twelve other bedrooms, a separate wing of domestic offices including thirteen staff bedrooms, stabling for twenty-three horses, garaging for four cars (presumably carved out of the stabling facilities) and a model laundry.

The nerve centre of the house was a spacious sky-lit central hall, two storeys high. Opening off it at ground-floor level were Percy’s suite of rooms – bedroom, bathroom, dressing room, study – and the reception rooms – billiard room, waiting room, smoking room, dining room, adjacent dining service room, and the long south-facing drawing room and music room, connected by double doors, where floor-to-ceiling French windows revealed a wide grass terrace melding gently into the misty Downs beyond. Magnolia trees clustered up against those walls, with a border of roses, myrtles and rosemary beneath. Spiralling stone staircases in the hall’s corners led up to a vaulted, cloistered gallery overlooking the hall, off which were the family’s bedrooms; and up again to the nurseries and housemaids’ rooms on the top floor. The lower ground floor was the masculine domestic sphere. There the under-butler slept, guarding the gun room, wine cellars and butler’s pantry where the family silver and other valuables were locked in the plate closet.

There too were the butler’s sitting room, odd-man’s room, lamp room, gun room and brushing room, dedicated entirely to brushing dirt off woollen clothes.

The servants’ offices, where the majority of Clouds’ thirty-odd indoor staff slept, were connected to the main house on the ground floor through the dining service room and on the lower ground floor by a web of subterranean passages. The offices were a long, low wing designed by Philip Webb to look like a series of cottages, with un-cottage-like proportions. The beamed servants’ hall was nearly 40 feet long; the housekeeper Mrs Vine’s bedroom and sitting room two-thirds as large. The housekeeper’s ground-floor rooms led directly to the china closet, the table linen room, the still room, store rooms, larder, game larder and bakehouse: all her responsibility and domain. Forbes the butler slept on the first floor, next to the footmen’s rooms, where he could keep an eye on them. Footmen, chosen specifically for their height, good looks and turn of calf, were apt to be troublesome. Further rooms for visiting valets were beyond. At the far end of the offices was the gardener’s cottage of Harry Brown, who had come with the Wyndhams from Wilbury; beyond that stood the stables with their controversial bricks.

The vast kitchen was modelled on a medieval abbot’s kitchen at Glastonbury. Huge joints of meat roasted on a spit over the fire kept turning by a hot-air engine. The dripping, caught in a vat beneath, was sold to East Knoyle’s villagers for a penny per portion. Next door the scullery maids scrubbed stacks of dishes and dirty pans. In a separate laundry building containing washing house, ironing room and drying room, four local girls washed and rinsed muslins, linens, cottons and woollens three days a week, mangling, starching and ironing for another two. A house like Clouds might go through on average 1,000 napkins a week; soap and soda were delivered annually by the ton and half-ton.

The imaginative gardens, designed for tête-à-têtes, were a collaboration between Madeline Wyndham and Harry Brown. Madeline’s bedroom on the main house’s east side overlooked a series of gardens, walled on one side by the offices (which were covered in vines and fig trees). The gardens were ‘a succession of lovely surprises’, said Harry Brown, with rose gardens, yew hedges clipped to resemble peacocks’ tails, a chalk-walled spring garden blooming annually with tulips, narcissus and cyclamens, and a pergola garden. The garden to the house’s north-west, with its winding ‘river walk’ (so-called by the family), was wilder. Cedar trees towered in the distance. The walk itself was planted with bluebells, primroses, Japanese iris, azaleas, bamboos, magnolias and rhododendrons.

When the Wyndhams moved in, the house was not quite complete. The hall’s chandeliers had yet to arrive; the drawing room’s intricate plasterwork was not finished until 1886. The plumbing was so full of glitches that Percy complained it required the assistance of the house carpenter and an engineer for ‘a common warm bath’.

The house had to be unpacked, and decorated. ‘Lately the floors have been strewn with scraps of carpet and we have stood with our heads on one side …,’ said a perplexed Mananai.

When finished, the house had a distinctive scent of cedar wood, beeswax and magnolias

and was decorated with near-monastic simplicity. Percy’s bedroom was papered in Morris print. Otherwise all the ground-floor rooms were painted white, their woodwork unpolished oak. Against the hall’s stone walls hung two large tapestries: ‘Greenery’ commissioned from Morris & Co., and a Flemish hunting scene. Over the vast fireplace was a large painting, believed to be by the Italian Renaissance painter Alesso Baldovinetti, of The Virgin Adoring the Christ Child with the Infant St John the Baptist and Angels in a Forest, bought by Percy at auction.