По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

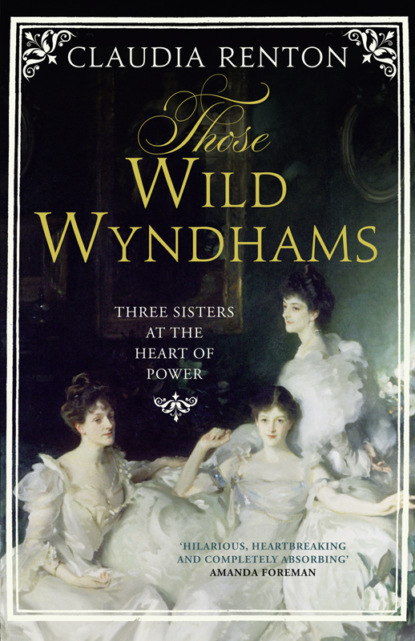

Those Wild Wyndhams: Three Sisters at the Heart of Power

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Socialism’s creed of political rights and economic equality for all was inherently inimical to Mary’s world. Yet for the aristocratic dowagers who, gorgon-like, lined the ballroom walls as chaperones to the young who danced before them, the more present threat came from capitalism: plutocratic fortunes from industry and finance trying to force entry into the hallowed drawing rooms of the landed elite. Throughout the 1880s the cry went up from within Society that the ruling class were losing their exclusivity, that young women were being presented at court whom nobody (by which it was meant nobody of ‘birth’) had ever seen. The percentage of women from the titled and landed classes presented at court fell from 90 per cent in 1841 to 68 per cent in 1871, to under 50 per cent in 1891.

Meanwhile the number of presentations was steadily increasing. In 1880, the year of Mary’s debut, a fourth drawing room was added to the social calendar, in 1895 a fifth. ‘Society, in the old sense of the term, may be said, I think, to have come to an end in the “eighties” of the last century,’ said Lady Dorothy Nevill in 1910.

The anxiety this caused was immense. ‘Let any person who knows London society look through the lists of debutantes and ladies attending drawing rooms and I wager that not half the names will be known to him or her,’ thundered one dowager in 1891, inveighing against the advent of ‘social scum and nouveaux riches’.

These dowagers’ underlying fear was that those forcing entry to their drawing rooms would use their seductive financial power to gain access to their children’s beds. The Season was a marriage market for the children of the elite. Within that market, matches were ‘facilitated’ by careful parents, rather than expressly arranged.

The convention was that a young couple should be in love – but with a socially and financially suitable mate. Consequently, access to that market needed to be strictly regulated, in order to prevent young aristocrats accidentally making the wrong choice, and pure bloodlines being corrupted by plutocratic wealth.

In fact, the English elite’s permeability has always been one of the key reasons for its continued survival. Its education system – Eton and Oxbridge – could with time turn the son of ‘social scum’ into a gentleman apparently indistinguishable from one whose bloodline goes back centuries. Yet it required thick skin. Mary’s friends Laura and Margot Tennant, the daughters of the Scottish industrialist Sir Charles Tennant, great-granddaughters of a crofter,

found that even after securing presentation at court, most doors were still closed to them, and, at the balls which they did attend, no men would dance with them. For Margot, social entrée came only when she managed to engage the Prince of Wales in conversation in the Royal Enclosure at Ascot. ‘I felt my spirits rise, as, walking slowly across the crowded lawn in grilling sunshine, I observed everyone making way for us with lifted hats and low curtsies,’ she recalled.

Even after the Tennant girls’ entry into Society their father was always known, to their aristocratic friends, in barely concealed mockery, as ‘the Bart’ – a reference to the baronetcy of which he was so obviously proud and the new money that had secured it.

For the aristocratic if bohemian Mary, who had access everywhere, what feathers she ruffled were of her own making. Writing her own memoir in later life, she remembered an incident with a young Oxford undergraduate, George Curzon:

As we were dancing we received the full impact of handsome Lady Bective’s train, formed of masses and masses and layers and layers of black tulle wired and strapped, about as heavy and powerful as a whale’s tail. It caught us broadside with immense force and we were swept off our feet and [hurled] to the ground and fell at my mother’s feet, our heads almost under the small hard gold chair on which she was patiently sitting as chaperone.

In old age, validated by decades of social success, Mary could look back on such youthful exuberance with pride. For her contemporaneous feelings we must turn elsewhere. Not to her diary: the journal that Mary kept religiously from the age of sixteen until her death was an object of record, not of confidence, and her entries generally masterpieces of pragmatism. That for 8 October 1884, by no means untypical, reads: ‘Put on orange frock, went down to tea, sat in draught, rested, black’.

It is far better to look to her sketches. On scraps of paper she drew top-hatted men about town carrying silver canes; strolling ladies in bustles and magnificent hats by day, drooping elegantly over their fans in ballgowns by night. She drew herself in balldress, shivering with cold in the early hours of the morning; bundled up against the chill spring in an umbrella and a muff; and on horseback, elegant in her riding habit, brandishing her riding crop under dripping trees in Hyde Park’s Rotten Row. On the back of an embossed thick card inviting ‘The Hon Percy & Mrs Wyndham & Miss Wyndham’ to one of Buckingham Palace’s two Court Balls each season is a caricature of herself entitled ‘Miss Parrot at the Ball’; she teased her little sisters with sketches depicting ‘Pretty Mary and her plain sisters’.

These sketches show the curious eye of an eager young woman getting to grips with the rules of a new, sophisticated world. Around this time Mary visited Dr Lorenzo Niles Fowler, a fashionable American phrenologist, in his Piccadilly offices. Phrenology, the art of analysing character by skull shape, is now discredited, not least for its unsavoury associations with eugenics. In the 1880s, it was Society’s latest craze. Dr Fowler must have been perceptive, since his report is curiously accurate. It describes an unselfconscious young woman, young for her years, and happy to let others – particularly her mother – take the lead; combative, but quick to forgive; loyal; and easily interested in other people. Interestingly, Dr Fowler also identified a normally well-hidden element of Mary’s personality. ‘You are remarkable for your ambition in one form or another,’ he said, commenting on her desire ‘to appear well in society, to attract attention, & to be admired’. This was undoubtedly true, and something Mary herself would always disavow.

She visited Dr Fowler at least twice more, taking her future husband with her too. Even given her love of novelty – Mary was always enthusiastic about the latest craze – it suggests she found some merit in his analysis.

In Thatched with Gold, Mabell Airlie expressed the conventional expectation of a debutante: to marry as soon as possible, preferably in her first Season. Too long a delay, and ‘there remained nothing but India as a last resort before the spectre of the Old Maid became a reality’.

A debutante’s social success was certainly measured out by proposals. Mary, who declared later that ‘Many wanted me to wife!’,

received more than a few. Nonetheless, her parents did not encourage her to marry straight away. They thought eighteen far too young to take on the responsibility of a husband and household, and were anyway reluctant to lose her to a husband so soon. Still, Mary did not become engaged until her fourth Season, in 1883. The delay was longer than Madeline Wyndham – responsible for guiding her daughter towards a suitable match, determined to prove her family’s worth by securing a splendid one – could have hoped for.

In the autumn of 1880 Balfour invited Mary and her parents to Strathconan, his Highland hunting lodge. The visit was not a success. Mary was tongue-tied with awkwardness: in her own words, ‘a shy Miss Mog … feeling very stiff & studying Green’s history & strumming Bach most conscientiously listening with silent awe to the flashing repartee, the witticisms & above all the startling aplomb of “grown-up conversation”’.

It may have been this muteness that gave rise to the story that some of Mary’s circle had initially thought her a little backward.

In London, Madeline and Mary invited Balfour to the Lyceum to see Ellen Terry in Much Ado About Nothing. Forever after the play would fill Mary with ‘a peculiar kind of sadness’. Twenty years on she remembered the evening with startling clarity: ‘We sat in a box and when the audience tittered at the wrong part you said savagely “I would gladly wring their necks” and I remember the sense of vague dissatisfaction when it was all over – the evening – one of my little efforts,’ she recalled to Balfour.

Balfour subsequently declined Madeline Wyndham’s invitations to visit the family at Wilbury. By the end of Mary’s second season it was clear that the affair had come to nothing.

Looking back over the abortive courtship many years later, Mary blamed her shyness and Balfour’s cowardice. She could not audaciously flirt like the Tennant sisters. She, like Shakespeare’s Beatrice, had needed luring. But Balfour was too ‘busy and captious’ to do it. ‘Mama wanted you to marry me [but] you got some silly notion in your head because … circumstances accidentally kept us apart – you were the only man I wanted for my husband and it’s a great compliment to you! … but you wouldn’t give me a chance of showing you nicely and you never came to Wilbury and you were afraid, afraid, afraid!’ she teased him.

Many biographers have examined in some detail why Balfour, at whom women flung themselves, never married. It has been suggested that the ‘Pretty Fanny’ of press caricatures was gay, even an hermaphrodite.

His devoted niece Blanche Dugdale suggested that he was nursing a lifelong broken heart after the death from typhoid in 1875 of his close friend May Lyttelton.

In fact, Mary’s analysis seems to hint at the most probable answer: Balfour was lazy, and emotion frightened him. He felt safest in a rational, logical world. ‘The Balfourian manner’ for which he became known ‘has its roots in an attitude of … convinced superiority which insists in the first place on complete detachment from the enthusiasms of the human race, and in the second place on keeping the vulgar world at arm’s length …’ wrote Begbie. In Begbie’s phrase, that world, which Balfour so charmed upon meeting, was never allowed to penetrate beyond his lodge gates.

A decade into their acquaintance, Mary pressed Balfour to express some kind of affection in his letters to her. He recoiled. ‘Such things are impossible to me: and they would if said to me give such exquisite pain, that I could never bring myself to say them to others – even at their desire,’ he explained.

In December 1880, Mary visited Wilton, home of the Earl and Countess of Pembroke. It was her first visit without her parents – she was chaperoned only by Eassy, her mother’s maid – and a suitably ‘safe’ first foray since Gertrude Pembroke and Madeline Wyndham had been close friends for many years. The house party included two men whom Mary knew only a little, but liked – Alfred Lyttelton (brother of May), ‘that nice youngest one’ of the large Lyttelton clan, and Hugo Charteris, eldest surviving son of Lord and Lady Elcho, heir to the earldom of Wemyss. The house party was rehearsing Christmas theatricals in a delightfully shambolic fashion. Mary was in her element. ‘We all turn our backs on the audience, we don’t speak up, we laugh, we hesitate and we gabble,’ she told her mother. ‘Hugo talks in a very funny voice.’

Acerbic, witty Hugo, a talented amateur actor, was far more attractive to women than his average looks suggested (he was balding fast). He was also a complicated soul, with a morose streak and a gambling problem. His gambling was often to complicate relations with his father, whose own high-minded preoccupation – army reform – earned him the sobriquet ‘the Brigadier’.

Two elder brothers had died in their early twenties (one an accident, the other a suspected suicide). Lady Elcho was a daunting figure even in the context of mid-Victorian evangelism, and never troubled to conceal from Hugo her feeling that the wrong sons had died.

‘Mums called Keems [Hugo] darling & patted him on the leg … neither of which has she done for years,’ Hugo noted with delight (referring to himself in the third person, something he often did in correspondence with his wife) when he was almost thirty years old.

Madeline Wyndham had known the Elchos for many years, not intimately but well. In February 1881 she invited Hugo to Wilbury. If she thought to capitalize upon interest sparked in Mary at Wilton, she was mistaken. When Madeline tried to make her daughter commit to a date, Mary professed an utter lack of interest. ‘As to Hugoman, his is an indefinite arrangement. I suppose you will write to him before the time comes [although] we might have him Monday as Lily [Paulet, Hugo’s cousin] comes that day,’ she wrote laconically in a letter otherwise devoted to plans for rearranging balls so that her friend and neighbour Louisa Gully might attend.

Recalling this period a few years later, Mary gloated over her inscrutability: ‘poor Mum … she really couldn’t fathom Migs,’ she said, describing herself proudly as ‘the little hunter (who always hunted on her own hook & followed her own trail)’.

Madeline persisted nonetheless. Six months later, Hugo was posted to Constantinople as part of a short-lived stint in the Foreign Office. By this time, his acquaintance with Mary was well established. Mary wrote to him on the eve of his departure recounting her recent nineteenth-birthday celebrations at Wilbury, where she had, in accordance with family tradition, been crowned with a wreath of roses and spent the evening celebrating with songs and dancing. She had decided, she told him, that ‘the [cat]’ – and here she drew a little cartoon of a cat – ‘believes the [hog]’ – a drawing of a pig – ‘to be most sage, large-minded and kind’.

Meritocracy had not reached the Foreign Office. It was believed that only those with breeding could properly and confidently uphold British prestige abroad. Lord Robert Cecil commented that all a junior attaché needed was fluent French and the ability ‘to dangle about at parties and balls’.

Several months later, bored and lonely in Constantinople, Hugo received a letter from his brother Evan, updating him on London gossip, including a nugget concerning a putative rival, David Ogilvy, heir to the earldom of Airlie:

Apparently he [Ogilvy] came over here in the summer intending to stay for a year and a half but went back after two months as Miss Wyndham was too much for him. He never proposed to her but was afraid he would do so, so he retired. I suppose you keep up constant correspondence with her I daresay she has told you more about Ogilvy than I can …

On that mischievous note, Evan swore Hugo to secrecy.

Mary most certainly had not gossiped. Hugo only discovered the truth of the matter several years later. ‘I think that Mumsie [Madeline Wyndham] proposing to Ogles for you & being refused is very funni [sic],’ Hugo told Mary gleefully upon discovering the real sequence of events in 1887.

Mary, like her husband employing the third person, blusteringly denied all responsibility: ‘It had nothing to do with Migs, it was entirely the old huntress’s transaction … I didn’t care a hang about Ogles & knew he didn’t care a rap for me … Mumsie wanted Migs to be clear of Ogles (or engaged to him!!!) to “go in” for Wash [Hugo himself] with a clean nose!’

It is quite possible that Ogles was the unnamed beau who allegedly abandoned his interest in Mary with the explanation that she was ‘A very nice filly, but she’s read too many books for me’.

Hugo returned to England in the spring of 1882, bearing bangles ‘for Miss Mary’, and determined to start a new career in politics as a member of the Conservative Opposition.

Mary was in Paris, flirting with Frenchmen and having ‘a high old time’. Madeline Wyndham ‘hunted’ her annoyed daughter back to Wilbury and dismissed her wheedling attempts to secure an invitation for a handsome ‘Musha de Deautand’ whom she had met in Hyères with the excuse that there was no room. ‘[T]here would be no harm done just a fortnight in the country … the house is elastic you could shove somebody somewhere,’ pleaded Mary, to no avail.

Madeline Wyndham was decided. As Mary later recalled, her mother’s plan was that she was to ‘go in’ for Hugo and marriage ‘in the summer (together with reading & music!) that makes me laugh! Hunt the arts to keep one’s hand in!’

That summer was one of the bloodiest politically for some time. In May, Parnell and his lieutenants William O’Brien and J. J. O’Kelly were released from several months’ imprisonment in Kilmainham Jail. They had been jailed for ‘treasonable practices’ after fomenting opposition to Gladstone’s 1881 Land Act, which gave Ireland the ‘3 Fs’ of fair rents, fixity of tenure and free sale of landholdings but which Parnell and his party considered did not go far enough. Their incarceration had thrown Ireland back into full-blown chaos: a national rent strike by day, while the mysterious ‘Captain Moonlight’ terrorized landlords by night. The ‘Kilmainham Treaty’ released Parnell in return for his bringing his influence to bear to end the rent strike. Many thought it negotiating with terrorists, including W. E. Forster, who in fury resigned as Irish Chief Secretary. His replacement, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and his Under-Secretary Thomas Burke had barely set foot on Irish soil when they were murdered in Dublin’s Phoenix Park by a gang calling itself the Invincibles. In London, men poured, hatless, out of their clubs to disseminate the appalling news.

Quite unjustly, Parnell and his fellow Irish parliamentarian John Dillon were blamed; arriving at the House of Commons the following day, Wilfrid Blunt was told that they were the ‘conspirators’. Stoutly, Blunt refused to give credence to the rumours: ‘they looked very much like gentlemen among the cads of the lobby’.

Blunt was preoccupied with another devastating blow to nationalism dealt by Gladstone’s ministry in Egypt. In 1882, the British occupied Egypt, in order to shore up the corrupt Khedive’s unstable rule in the face of revolt by Colonel Ahmed Orabi, popularly known as the Arabi Pasha. The need to protect the interests of the ‘bondholders’, as those numerous Britons with investments in Egypt were now called, outweighed any nice concerns for Midlothian principles of national self-government. So firmly did the British believe that Suez must be protected that just nineteen members of the House of Commons voted against the occupation. Percy Wyndham was the only Tory to do so, vigorously opposed to what he believed to be Britain’s illegal and oppressive behaviour.

He later made one of his increasingly rare Commons speeches on Blunt’s behalf, for Blunt’s fierce advocacy of the Arabi’s cause – even to the extent of paying for his legal defence when the Arabi was court-martialled (the trial was abandoned, and the Arabi exiled instead) – earned Blunt exile himself. In July 1884, trying to go back to Egypt, Blunt was detained at Alexandria by British officials who, under instructions from Sir Edward Malet, the Consul General, forbade the troublemaker entry.

Access to a parliamentary seat was still easy for a young aristocrat. In January 1883, Hugo’s grandfather died, and his father, now the tenth Earl of Wemyss, was elevated to the Lords. At a by-election in February, Hugo, having inherited his father’s courtesy title, stepped neatly into the Suffolk seat his father had held since 1847. Seamlessly, a Lord Elcho once more sat for Haddington. At Wilbury Mary, Mananai and Pamela decorated Mary’s dog Crack with yellow ribbons to celebrate – the colour of the Primrose League. The League, named after the favourite flower of Disraeli (who died in 1881), promoted working- and middle-class Toryism – the latter becoming known as Villa Toryism – largely through jamborees and summer fêtes, enticing the electorate with the promise of aristocratic proximity. It was the work of Lord Randolph Churchill, the preacher of ‘Tory Democracy’, an ill-defined creed that involved transferring power from the party’s leadership to the National Union – the constituencies – but was really part of his own bid for power. Privately, he described it as ‘chiefly opportunism’.

Throughout that year Hugo sent Mary bouquets which she unpicked and made into buttonholes for him to wear; they played lawn tennis, went to the theatre, had tea and walked in the park: all under Madeline Wyndham’s encouraging eye. Finally on a July night in 1883, with ‘buttonhole no. 171’ in his lapel, Hugo proposed and Mary said yes.

The next day, Hugo went to Belgrave Square to seek formally the Wyndhams’ blessing. Percy gave it to him ‘from my heart of hearts … Mary is a great treasure, and as I believe you know it I am very glad you have made her love you.’