По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

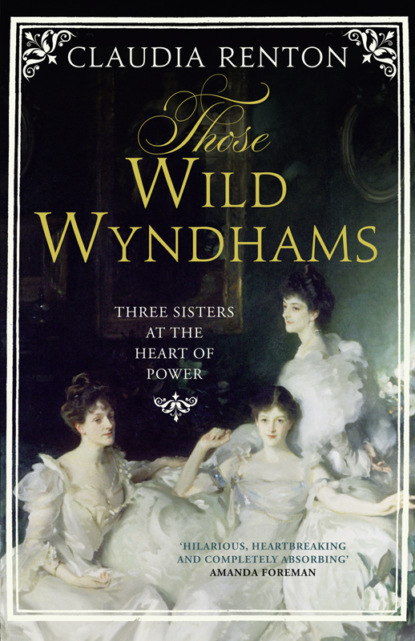

Those Wild Wyndhams: Three Sisters at the Heart of Power

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

For the Pre-Raphaelites and their heirs, beauty’s pursuit was not indulgence but necessity. Their dreamy art, born out of the Industrial Revolution, was intended to counteract, even arrest, the modern world’s ugliness. For Burne-Jones’s great friend and business partner William Morris, whose Oxford Street store, Morris & Co., was the favoured emporium of the English aesthetic classes, this philosophy led him to political activism and ardent socialism. Burne-Jones was content to improve society by feeding its soul through its eyes. The provision of art to cultivate and inspire the masses was now part of civic responsibility, reflected in the large public art galleries constructed in urban centres of the industrial north.

Mary’s early childhood in Cumberland was like a Pre-Raphaelite painting brought to life. The Wyndhams lived at Cockermouth Castle, a strange, half-ruined property on the River Cocker’s banks, until 1869. Afterwards they rented Isel Hall, an Elizabethan manor a few miles away. Madeline Wyndham took her children out among the heather to draw and paint, and read aloud to them Arthurian tales. At night she sang berceuses, French lullabies learnt from her own mother, and left them to sleep, soothed by the sound of the Cocker’s rushing waters and owls hooting in the dark. She had miniature suits of armour made for George and Guy. The children played at knights and damsels with Mary dressed in her mother’s long flowing skirts.

A portrait of eight-year-old Mary in Cumberland by the Wyndhams’ friend Val Prinsep, in the flat, chalky style characteristic of their artistic circle, shows a tall, round-eyed beautiful child. In wide straw hat and loose mustard-yellow dress, she gazes directly at the viewer, bundling in her skirts armfuls of flowers.

One of Mary’s earliest adventures in childhood was scrambling after her father through thick heather up Skiddaw, the mountain dominating the Cumbrian skyline, with a trail of dogs in search of grouse; then sleeping overnight in a little lodge perched on the mountainside.

In adulthood, Mary wrote lyrically of ‘the club & stag, the moss, the oak & beech fern, bog myrtle, & grass of Parnassus – Skiddaw in his splendid majesty – covered with “purple patches” (of heather) with deep greens & russet reds & swept by the shadows of the clouds – my heart leaps up – when I behold – Skiddaw – against the sky …’.

Mary considered herself a lifelong ‘pagan’, fearlessly finding freedom in wildness. She attributed these qualities to her Cumberland childhood. She mourned ‘beloved Isel’ when the Wyndhams finally gave it up in 1876. Ever after, Cumberland was a lost Arcadia to her.

When George was born in August 1863, Lady Campbell told Percy he ‘deserved a boy for having so graciously received the girl last year!’

In 1865 the Wyndhams had another boy, Guy. With two brothers so close to her in age, Mary was practically a boy herself. She learnt to ride on a donkey given to the children by Madeline when they were toddlers,

was taught to hunt and hawk by her father’s valet Tommy, and was keeping up with the hounds at just nine years old, even if, on that first occasion, she told her mother ruefully, ‘I did not see the fox.’

She kept pet rooks which she fed on live snails, and begged her mother for permission to be taken down a Cumberland coal mine by her brothers’ tutor.

Some summers, the Wyndhams visited Madeline’s favourite sister, Emily Ellis, at her home in Hyères, the French town at the westernmost point of the Côte d’Azur, which was becoming increasingly popular with the British. There Mary scrambled willingly along the narrow tunnels of the Grotte des Fées into a cavern of stalagmites and stalactites. While the other members of her party sat and ate oranges, she caught ‘a dear dear little soft downy long eared bat’ which, she informed her mother, in her father’s absence she had installed in his dressing room: ‘all day he sleeps hung up to the ceiling by his two hind legs’.

High spirited to the point of being uncontrollable, the children exhausted a stream of governesses. At Deal Castle in Kent, home of the Wyndhams’ friend Admiral Clanwilliam, Captain of the Cinque Ports, marine sergeants were deputed to drill the children on the ramparts to tire them out.

Their arrival in Belgrave Square’s communal garden, clad in fishermen’s jerseys, whooping and hollering on being released from their lessons, prompted celebration among their peers and anxiety among their playmates’ parents. At least one couple instructed their governess not to let her charges play with ‘those wild Wyndham children’.

In Mary’s stout babyhood Percy nicknamed her ‘Chang’ after a popular sensation, an 8-foot-tall Chinese who entertained visitors – for a fee – at Piccadilly’s Egyptian Hall. Mary grew into a ‘strapping lass’. ‘How well and strong I was, never tired,’ she said in later life, now thin and enervated, recalling wistfully her days as a rambunctious, lanky ringleader, strongest and most daring of the three siblings. ‘I was worse than 100 boys.’

The fairytale had a darker side. Madeline Wyndham concealed beneath her calm, loving exterior a mind seething with dread. She had a paranoid strain capable of rendering her literally insensible from anxiety. A childhood of loss – her father’s death when she was twelve, a beloved elder brother’s five years after that – during the years of the ‘Great Hunger’, the famine that, by death and emigration, diminished Ireland’s population by up to a quarter,

had a formative effect upon her. She was intensely spiritual, mystical and religious. Her deep foreboding of fate compounded rather than diminished that faith: ‘the memory of death gave to the passing hours their supreme value for her’, said her friend Edith Olivier.

Olivier had looked through Madeline’s vellum-bound commonplace books to find them crammed with dark thoughts. ‘All strange and terrible things are welcome, but comforts we despise,’ reads one entry.

‘God to her is, I think, pre-eminently the “King of Glory”,’ said Madeline’s son George in later years,

but in Madeline’s mind glory came as much from darkness as from light.

When, during the Wyndhams’ courtship, Madeline had confessed to bleak moods, Percy simply denied them. He did not think she was permanently in ‘low spirits’, he said, advising against articulating such thoughts lest ‘the hearer should think them stronger than they are and permanently there when in reality they are not’. For Percy, anxieties that seemed all consuming at the time dissipated within ‘half an hour’, a day at most, like clouds puffed across the sky.

In fact, Madeline’s volatile moods and her sporadic nervous collapses suggest that a strain of manic depression ran through the family – what George called the ‘special neurotic phenomena of his family’.

The impact on her children was intense. She invested in them all her apocalyptic hopes, determined they should succeed and prove her family’s merit, convinced the world conspired to bring them down. It is telling that, despite her undoubted love for her mother, Mary described Percy as ‘one of the people – if not the one that I loved best in the world – who was unfailingly tender & who loved me more than anyone did and without whose sympathy I have never imagined life’.

The Wyndhams’ tribe naturally split between Mary, George and Guy, the trio born in the early 1860s, and the ‘little girls’, Madeline (known as ‘Mananai’, from what was obviously a childish attempt to pronounce her name) born in 1869 and Pamela in 1871.

As a consequence of Lord Leconfield’s death in 1869 their early childhoods were also markedly different.

Leconfield, intensely disliking his heir Henry, left everything that was not tied up in an entail to Percy. He created a trust for Percy and his heirs of a Sussex estate (shortly afterwards sold to Henry for £48,725 8s 10d),

land in Yorkshire, Cumberland and Ireland, £15,000 worth of life insurance and £16,000 worth of shares in turnpike roads and gas companies, and made provision for the trustees to raise a further £20,000 from other Sussex land. Percy received outright the family’s South Australian estates (bought by Percy’s maverick grandfather, the third Earl of Egremont, Turner’s patron and three-times owner of the Derby winner, for his estranged wife); most of the household effects from East Lodge, a Brighton family property, including thirty oil paintings and all the plate; the plate from Grove, another family property; and the first choice of five carriage horses. Leconfield’s will was a calculated, devastating snub to Henry. For a while, the Wyndhams continued to visit Henry and his wife Constance at Petworth, but soon enough the brothers had a spectacular row over the port after dinner. The resulting estrangement between the families lasted for almost a decade,

despite all the attempts of their wives, still close friends, to heal it.

Leconfield’s death provoked the Wyndhams’ move to Isel from Cockermouth Castle, which now belonged to Henry; and his will made them rich. Percy and Madeline now commissioned Leighton and his architect George Aitchison to decorate Belgrave Square’s entrance hall. The Cymbalists was a magnificent mural painted above the central staircase – five life-sized, classical figures in a dance against a gold background. Above that was Aitchison’s delicate frieze of flowers, foliage and wild birds in pinks, greens, greys and powder blue. Even the most unobservant visitor could see this was an artistic house.

Shortly after Leconfield’s death, Percy visited his sister Blanche and her husband Lord Mayo in India, where Mayo was Viceroy. (Mayo had previously served as Ireland’s Chief Secretary for almost a decade, and it was Blanche who had introduced Percy to Madeline, when Percy visited them in Ireland.)

While Percy was abroad, Lady Campbell, in her seventies, was suddenly taken ill. Madeline Wyndham hastened to Ireland with newborn Mananai, Guy and Horsenail, leaving Mary and George, with their governess Mademoiselle Grivel, at Mrs Stanley’s boarding house in Keswick, Cumberland. ‘… I am so sorry that dear Granny is so ill for it must make you so unhappy. George and I will try to be very good indeed so as to make you happy,’ Mary wrote to her mother.

Lady Campbell died shortly afterwards, and Madeline made her way back to her elder children: ‘so glad I shall be to see you my little darling … you were so good to me when I was so knocked down by hearing such sad news’.

Almost precisely upon Madeline and Percy’s reuniting, Madeline fell pregnant. Pamela Genevieve Adelaide was born in January 1871, at Belgrave Square like all her siblings.

The little girls were born into the age of Gladstone. In 1867, Disraeli had pushed Lord Derby’s Tory ministry into ‘the leap in the dark’: the Reform Act that gave the vote to all male householders in the towns, as well as male lodgers who paid rent of £10 a year or more for unfurnished accommodation, almost doubling the electorate. In the boroughs, the hitherto unenfranchised working classes were now in the majority. The debate over the Act was fought with passion on both sides: for most, democracy was a demoniacal prospect signifying mob rule. A series of unruly popular protests organized by the Radical-led Reform League, with hordes brandishing red flags and wearing the cap of liberty marching on Trafalgar Square, did little to dispel these fears. In a notorious incident of July 1866 – just a stone’s throw from Belgrave Square – a mob of 200,000 tore down Hyde Park’s railings when the Government tried to close it to public meetings, overwhelming the police ‘like flies before the waiter’s napkin’.

Contemporary theorists were concerned that vox populi would become vox diaboli. In The English Constitution Walter Bagehot expressed his fear that ‘both our political parties will bid for the support of the working man … I can conceive of nothing more corrupting or worse for a set of poor ignorant people than that two combinations of well-taught and rich men should constantly offer to defer to their decision and compete for the office of executing it.’

The equally bleak predictions by Lord Cranborne, later Marquess of Salisbury – who resigned in protest from Derby’s ministry upon the passing of the Act – seemed confirmed when the electorate returned Gladstone in the 1868 elections, at the head of the first truly Liberal ministry, a disparate band of Radicals of the industrial north, Whig grandees, some still speaking in their eighteenth-century ancestors’ curious drawl, and Dissenters, the non-conformists who wanted to loosen the hold of the established Church. Gladstone immediately announced his God-given mission to ‘pacify Ireland’ (provoked, in part, by the Fenian bombing of Clerkenwell Prison the previous year that had killed twelve civilians and injured forty more)

and set about disestablishing the Irish Church, while dealing several blows to the hegemony of the British landed classes by introducing competitive exams for the civil service, abolishing army commissions and removing the religious ‘Test’ required for fellows of Oxford, Cambridge and Durham universities to enable non-Anglicans to hold those posts.

Percy, like his father before him, was a Tory of the oldest sort, who believed that his class’s God-given duty to govern through wise paternalistic rule not just the tenantry on their estates but the country as a whole was under attack. For Percy, like most Tories, authority was ‘like a sombre fortress, holding down an unpredictable population that might, at any moment, lay siege to it’.

In 1867, Percy had commissioned Watts to paint Madeline’s portrait. The portrait took three years to complete, partly because painter and sitter, kindred artistic souls, enjoyed their conversations so much they were reluctant for them to end.

In a nod to classical portraiture the statuesque Madeline, in her early thirties, gazes down at the viewer from a balustraded terrace. A mass of laurel, signifying nobility and glory, flourishes behind her; in the foreground a vase of magnolias denotes magnificence. Her gown is loose and splashed with sunflowers, proclaiming her allegiance to the world of the Pre-Raphaelites; the gaze from hooded eyes under swooping dark brows direct and forthright. The portrait, hung in Belgrave Square’s drawing room, made its first public appearance – to quite a splash – some seven years later, on the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery, a private venture of the Wyndhams’ friends Sir Coutts and Lady Lindsay on London’s New Bond Street. It caught the eye of Henry James, recently arrived in England, reviewing the exhibition for the Galaxy. He told his readers of his companion’s comment: ‘It is what they call a “sumptuous” picture … That is, the lady looks as if she had thirty thousand a year.’ ‘It is true that she does,’ said James, praising nonetheless ‘the very handsome person whom the painter has depicted … dressed in a fashion which will never be wearisome; a simple yet splendid robe, in the taste of no particular period – of all periods’.

James had seen that the aristocrat effortlessly superseded the artist. And, although it was kept well hidden beneath her friendships with artists, her undoubted talent and her air of vague, bohemian warmth, Madeline Wyndham was acutely aware of social gradations. ‘You and Papa are rather stupid about knowing who people are!!’ she told Mary, half jokingly, half in frustration as she discussed the ‘belongings’ of fellow guests at a house party – by which she meant their connections and titles.

She assiduously cultivated the boring Princess Christian as a friend. ‘She is a humbug,’ declared the middle-class Philip Burne-Jones (son of Edward and Georgiana), finding that Madeline’s warmth towards him as a family friend cooled rapidly when he made plain his hope that he could court Mary, with whom he had been in love since childhood.

It has been said that Madeline, with her artful eye, the creator of Clouds, the exquisite Wiltshire house into which the Wyndhams moved in 1885, is the model for Mrs Gereth in Henry James’s The Spoils of Poynton, the story of a jewel-like house created out of the ‘perfect accord and beautiful life together’ of the Gereths: ‘twenty-six years of planning and seeking, a long sunny harvest of taste and curiosity’. Mrs Gereth is an unscrupulous obsessive who tries to manipulate her son into marrying a worthy chatelaine, then sets the house aflame rather than see it pass into the wrong hands. If Madeline Wyndham is the model, there is no clearer indication of the steel within her soul.

Extravagantly generous – she kept open table at Belgrave Square, with sometimes forty people unexpectedly sitting down to lunch

– Madeline never spoke of the sudden change in her fortunes brought about by marriage, only fondly recollecting an Irish childhood in a ‘nest of lovely sisters’ visiting relations in pony and trap.

Her ambitions for her family were tied up with her anxiety to prove that Percy’s gamble in marrying her had exalted his clan. When her daughters married, she was terrified that one might bear a child with some ‘defect’.

It is clear that she feared what might be latent in her blood.

In the early 1870s, Madeline had an affair with Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, a handsome poet and Percy’s cousin and close friend who had spent part of his childhood living in a cottage on the Petworth estate. Blunt and his wife Lady Anne spent much of their time travelling in Africa and the Middle East, and bought an Egyptian estate just outside Cairo named Sheykh Obeyd, after the Bedouin saint Obeyd buried in the grounds.

They spoke vernacular Arabic, and Blunt, a self-professed iconoclast, adopted Bedouin dress even in England.

At Crabbet Park, Blunt’s Sussex estate, they founded a successful stud breeding Arab horses. The annual sale and garden party was a fixture of the Season: ‘everybody who was anybody in London went in those days to Crabbet for the sale of the Arabs [sic],’ wrote the journalist Katharine Tynan, recalling Janey Morris, Oscar Wilde and Jane Cobden, radical daughter of the reformer Richard Cobden, wandering through the beautiful grounds.

The intrepid Arabists: Wilfrid Blunt and Lady Anne Blunt in the late 1870s.