По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

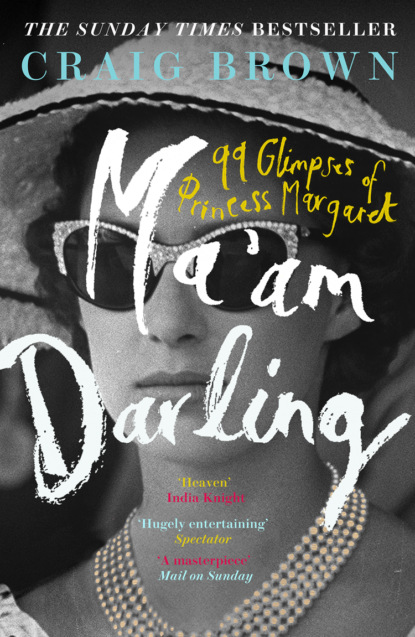

Ma’am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In the end, having delayed for sixteen years, Crawfie married George ‘very quietly’ in Dunfermline ‘without any fuss’ the following year, just a couple of months before Lilibet married Prince Philip. Lilibet gave them a coffee set as a wedding present, and Margaret gave them three bedside lamps. But Crawfie’s job was not yet done: leaving her new husband behind in Scotland, she returned briefly to her position at the Palace, alone now with Margaret.

The final pages of The Little Princesses are devoted to a portrait of Margaret at seventeen. Though sugar-coated, they leave a slightly bitter after-taste. ‘She is learning with the years to control her sharp tongue’ … ‘It is a grief to her that she is so small, and she wears shoes and hats that give her an extra inch or so’ … ‘Margaret is more exacting to work for than Lilibet ever was’ …

(Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

At one point, Crawfie grows worried about Margaret and speaks to the Queen ‘quite openly’ about her socialising: ‘I can do nothing with her. She is tired out and absolutely exhausted with all these late nights.’ Between the two of them, the Queen and the governess agree that in future Margaret must spend one or two nights a week quietly at home, rather than out gallivanting.

The memoir ends, rather abruptly, with the birth of Prince Charles in November 1948. At the end of the year, Marion Crawford was finally permitted to retire. By now Princess Margaret was eighteen years old, pert, wilful, and intent on pursuing a life unsupervised.

17 (#ubebacbea-06c5-570e-9c15-1d256ab24093)

On 22 March 1949, the Conservative MP David Eccles was sitting in the chamber of the House of Commons, listening to a speech ‘so excessively boring’ that, for want of anything better to do, he suggested to a neighbouring MP that they should ogle a pretty girl who had come to hear the debate from the Speaker’s Gallery. The two made flirtatious signs to her, to which she was quick to respond. The next day, Eccles was surprised to hear that he had been flirting with the eighteen-year-old Princess Margaret. He was both annoyed with himself for having made such a mistake, and surprised she had responded so readily.

By the following year, Margaret’s adoption as a sort of national sex symbol had gathered pace. ‘Is it her sparkle, her youthfulness, her small stature, or the sense of fun she conveys, that makes Her Royal Highness Princess Margaret the most sought-after girl in England?’ asked Picture Post in the summer of 1950. ‘And this not only amongst her own set of young people but amongst all the teenagers who rush to see her in Norfolk and Cornwall, or wherever she goes.’

Though her face and her figure were similar to her elder sister’s, it was generally agreed that it was Princess Margaret who had that certain something. Was this because even the most hot-blooded British male felt that his future monarch existed on a plane beyond lust, while the younger sister was still flesh and blood? Or was Margaret blessed with more S.A., as it was known at the time? Did men detect a sparkle in her eyes which suggested that she, unlike her sister, might, just possibly, be tempted? In later life, Margaret could be surprisingly candid about her youthful impulses. She once told the actor Terence Stamp that as a teenager she entertained sexual fantasies about the workmen she could see out of the Buckingham Palace windows. It is hard to imagine the Queen ever sharing such secrets.

Nearly ten years after the Eccles incident, on 18 December 1958, the publisher Rupert Hart-Davis gazed moonily as the Princess presented the Duff Cooper Prize to the fifty-two-year-old John Betjeman. Hart-Davis confessed to his old friend George Lyttelton that he had ‘completely lost my heart’ to her: ‘My dear George, she is exquisitely beautiful, very small and neat and shapely, with a lovely skin and staggering blue eyes. I shook hands with her coming and going, and couldn’t take my eyes off her in between.’

(The Times/News Syndication)

According to his friend Lady Diana Cooper, Betjeman himself was so overwhelmed by the presence of the young Princess that he was ‘crying and too moved to find an apology for words’. Looking on with the doubly hard heart of the academic and the satirist, his waspish friend Maurice Bowra, the chairman of the judges, penned ‘Prize Song’, a parody of Betjeman’s poem ‘In Westminster Abbey’:

Green with lust and sick with shyness,

Let me lick your lacquered toes.

Gosh, O gosh, your Royal Highness,

Put your finger up my nose,

Pin my teeth upon your dress,

Plant my head with watercress.

Only you can make me happy

Tuck me tight beneath your arm.

Wrap me in a woollen nappy;

Let me wet it till it’s warm

In a plush and plated pram

Wheel me round St James’s Ma’am …

Lightly plant your plimsolled heel

Where my privy parts congeal.

Bowra circulated this poem among friends, one of whom, Evelyn Waugh, pronounced it ‘excellent’.

Another poet, Philip Larkin, eight years her senior, continued to nurture a private passion for the Princess well into her middle age. ‘Nice photo of Princess Margaret in the S. Times this week wearing a La Lollo Waspie, in an article on corsets. See what you miss by being abroad!’ he wrote to the distinguished historian Robert Conquest in June 1981, when the Princess was fifty years old, and Larkin fifty-eight.

Alas, Larkin’s lust for Margaret never blossomed into verse, though he was once almost moved to employ her as a symbol of his perennial theme, deprivation. On 15 September 1984 he wrote to his fellow poet Blake Morrison that though the birth of Prince Harry had done nothing for him – ‘these bloody babies leave me cold’ – he had nonetheless ‘been meditating a poem on Princess Margaret, having to knock off first the booze and now the fags – now that’s the kind of royal poem I could write with feeling’. Stephen Spender, too, recognised a kindred spirit in the Princess. At the age of seventy he reflected that ‘being a minor poet is like being minor royalty, and no one, as a former lady-in-waiting to Princess Margaret once explained to me, is happy as that’.

Her admirers came from less rarefied circles too. Ralph Ellison, author of The Invisible Man, a novel about the struggles of a young African-American man in a hostile society, was presented to her on a trip to Europe in 1956. He described his encounter in a letter to his friend and fellow novelist Albert Murray.

‘I was one of the lucky ones who were received by the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret, two very charming ladies indeed.’ The Princess was, he added, ‘the kind of little hot looking pretty girl … who could upset most campuses, dances, clubs, bull fights, and three day picnics even if she had no title’. At that time, the Princess had just turned twenty-six.

18 (#ubebacbea-06c5-570e-9c15-1d256ab24093)

It was in the early 1950s that Pablo Picasso first began to have erotic dreams about Princess Margaret. Occasionally he would throw her elder sister in for good measure. From time to time Picasso shared these fantasies with his friend the art historian and collector Roland Penrose, once even confiding in him that he could picture the colour of their pubic hair.

Picasso often had dreams about celebrities. In the past, both de Gaulle and Franco had popped up in them, though, mercifully, never in a sexual context. But the two royal sisters were another matter. ‘If they knew what I had done in my dreams with your royal ladies, they would take me to the Tower of London and chop off my head!’ Picasso told Penrose with pride.

Having moved into his vast villa, La Californie, in 1955, he set his sights on marrying the only young lady he deemed smart enough for it. There was, he said, just one possible bride for him: Princess Margaret. Not only was she a leading member of the British Royal Family, but she was also his physical type: shorter than him (at five foot four inches, he towered over her), with beautiful skin and good strong teeth. In pursuit of this fantasy, he ordered the waspish British art dealer Douglas Cooper to drop in on Her Majesty the Queen and request her younger sister’s hand in marriage. Picasso made it clear that this was more than a whimsy. He would not let the matter drop, growing more and more absorbed in plotting the right strategy. He would draw up a formal document on parchment, in French, Spanish or Latin, for Cooper to present to Her Majesty on a red velvet cushion. Cooper would be accompanied by Picasso’s future biographer John Richardson, who would arrive dressed as a page or herald, complete with trumpet.

‘If we didn’t have the right clothes, Picasso would make them for us: cardboard top hats – or would we prefer crowns?’ recalled Richardson. ‘He called for stiff paper and hat elastic and proceeded to make a couple of prototypes. His tailor, Sapone, would help him cut a morning coat out of paper.’

There would be no place in Picasso’s married life for his current girlfriend, Jacqueline: she would have to go to a nunnery. Picasso turned to Jacqueline. ‘You’d like that, wouldn’t you?’ ‘No Monseigneur, I wouldn’t. I belong to you.’

By the end of their day of planning, the artist dressed Cooper and Richardson in the ties and paper crowns he had made for them, emblazoned with colourful arabesques. ‘Now you look ready to be received by the Queen,’ he declared, before checking that they knew how to bow with the appropriate panache.

Picasso’s fascination with Princess Margaret stayed close to fever pitch for a decade or more. In June 1960, he missed meeting her when she paid a surprise visit to his Tate Gallery exhibition. Never again would he be offered a better opportunity for saying, ‘Come upstairs and let me show you my etchings.’ But he was stuck in France, which meant that Roland Penrose, the exhibition’s curator, was obliged to convey the Princess’s reactions by post.

‘My dear Pablo,’ wrote Penrose, giddy with excitement, ‘… on Thursday, a friend of the Duke informed me – in the greatest secrecy so as to avoid a stampede to the Tate of all the journalists in the world – that the Queen wanted to come in the evening with a dozen friends to see the show. I wasn’t to say a word to anyone and no official was to be present to show them the pictures, only me. And that’s exactly what happened. The Queen and the Duke arrived first and later the Queen Mother joined them.’

The Royal Family, he informed the great painter, ‘has never shone in their appreciation of the arts … your work really did seem to touch them, perhaps for the first time at the depths of their being’.

Everyone had been bowled over by Picasso’s brilliance: ‘… yet again I must thank you – your superb presence surrounding us everywhere gave me confidence, and the eyes of the Queen lit up with enthusiasm – with genuine interest and admiration … I’d been advised not to insist on the difficult pictures and to avoid going into the cubist room – but I wasn’t happy about that and to my delight she went in with an enthusiasm that increased with each step – stopping in front of each picture – “Picture of Uhde”, which she thought magnificent, “Girl with a Mandolin”, “Still Life with Chair Caning”, which she really liked, the collages, the little construction with gruyere and sausage in front of which she stopped and said, “Oh, how lovely that is! How I should like to make something of that myself!”’

Penrose injected a note of suspense into his account by leaving until the very last moment the surprise entrance of Picasso’s intended. After the rest of the royal party had made appropriate noises about the great still life of 1931 (‘very enthusiastic’) and the paintings of the Guernica period (‘very disquieted’), ‘at last we reached the Bay of Cannes, which the Queen Mother found superb, when someone else joined us – and turning to me the Queen said, “May I introduce my sister Margaret?” And there she was, the beautiful princess of our dreams with her photographer husband …’

The Queen then said she would have to leave shortly, and asked Penrose to show her sister the entire exhibition all over again. Tactfully, he drew a veil over the persistent presence of Snowdon, scrubbing out ‘her photographer husband’ from the rest of his account, and focusing solely on the Princess: ‘When she asked me whether you were going to come I said I thought that, even though you had expressed no desire to come, you would be sad not to have been there to meet her this evening. And she smiled enchantingly and I think I glimpsed a blush spreading beneath her tan.’

Once the royal party had finally departed, Penrose scribbled a few notes, solely for his own consumption. These suggest that all the various members of the Royal Family – Princess Margaret being the last to arrive – were far more slothful in their appreciation of the artworks than he suggested in his letter to Picasso. In these jottings, ‘M’ is Margaret, ‘P’ is Philip, ‘Q’ is the Queen, and ‘QM’ the Queen Mother:

Great interest in Uhde. Q.

‘I can see character in it.’ Q.

‘I like letting my eyes wander from surface to surface without worrying about what it means.’ M

P coming in: ‘DO realise, darling, there are 270 pictures to see and we have hardly begun.’

‘Why does he use so many different styles?’ Q.