По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

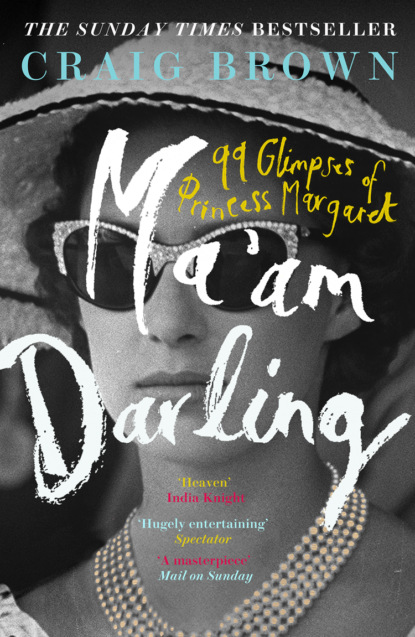

Ma’am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

King George VI died early the following year. The Princess had been devoted to him, and he to her. ‘Lilibet is my pride. Margaret is my joy,’ he once said, adding on another occasion, ‘She is able to charm the pearl out of an oyster.’ Lilibet was dutiful and serious; Margaret wilful and fun. ‘She it was who could always make her father laugh, even when he was angry with her,’ wrote John Wheeler-Bennett, the official biographer of George VI. On one occasion she interrupted a telling-off by saying, ‘Papa, do you sing, “God Save My Gracious Me”?’ The King had burst out laughing, and all was forgiven.

His death hit her hard. ‘It was a terrible blow for Princess Margaret,’ a friend remembered. ‘She worshipped him and it was also the first time that anything really ghastly had happened to her.’ Margaret confirmed this to Ben Pimlott, the biographer of her sister: ‘After the King’s death there was an awful sense of being in a black hole. I remember feeling tunnel-visioned and didn’t really notice things.’ In her grief, did she seek refuge in love?

After the King’s death, everyone moved up or down a notch: Queen Elizabeth became Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, Princess Elizabeth became Queen Elizabeth II, and Townsend was appointed comptroller of the Queen Mother’s household. Only Margaret stayed the same, but now she had to live alone with her mother in Clarence House, eclipsed and to some extent marginalised by her sister, the new Queen, and with no clear role of her own.

The following December, after eleven years of marriage, nine of them in the service of the Royal Family, Peter Townsend divorced Rosemary, who was named as the guilty party. Two months later she married John de Lázsló, son of the fashionable society painter Philip de Lázsló.

That winter, according to Townsend, he and the Princess found themselves alone in the Red Drawing Room of Windsor Castle. They spoke for hours on end. ‘It was then,’ he writes, ‘that we made the mutual discovery of how much we meant to one another. She listened, without uttering a word, as I told her, very quietly, of my feelings. Then she simply said: “That is exactly how I feel, too.”’

Or that’s how his story goes. But had this impetuous young woman really managed to hide her feelings for a full five and a half years? And had the Group Captain somehow exercised a similar restraint?* (#ulink_71c1798d-2b15-543f-89b9-8830a1b3037e)

According to Townsend, they pursued their romance in the open air, walking or riding, always ‘a discreet but adequate distance’ from the rest of the party. ‘We talked. Her understanding, far beyond her years, touched me and helped me; with her wit she, more than anyone else, knew how to make me laugh – and laughter, between boy and girl, often lands them in each other’s arms.’ Once again, he describes himself as a boy; but by now he was thirty-eight years old, and middle-aged. ‘Our love, for such it was, took no heed of wealth and rank and all the other worldly, conventional barriers which separated us,’ he continues. He doesn’t mention less romantic barriers such as age, children (by now he had a second son) and his recent divorce. ‘We really hardly noticed them; all we saw was one another, man and woman, and what we saw pleased us.’

The news of their pleasure, ‘delivered very quietly’, went down like a lead balloon with the senior courtier Sir Alan ‘Tommy’ Lascelles, at that time private secretary to the new Queen. ‘You must be either mad or bad,’ he informed Townsend. The Princess was to credit Lascelles with ruining her life. ‘Run the brute down!’ she instructed her chauffeur, decades later, when she spotted Lascelles, by now an old man, through her car window.

Margaret had already confessed her love to Lilibet, who invited her and the Group Captain to dinner à quatre with herself and Prince Philip, an evening that passed off, in Townsend’s view, ‘most agreeably’, though ‘the thought occurred to me that the Queen, behind all her warm goodwill, must have harboured not a little anxiety’.

Margaret also told the Queen Mother. Townsend insists that she ‘listened with characteristic understanding’, though he attaches a disclaimer to this: ‘I imagine that Queen Elizabeth’s immediate – and natural – reaction was “this simply cannot be”.’

But one of the hallmarks of the Queen Mother was resilience, maintained by a steadfast refusal to acknowledge anything untoward. Whenever she caught a glimpse of something she did not like, she simply looked the other way, and pretended it was not there. Margaret, on the other hand, liked to let things simmer, sometimes for decades.

* (#ulink_c56a4e1d-02a8-5632-b2e8-f50d365f2349) Possibly not. Princess Margaret’s chauffeur, John Larkin, recalled a conversation with his employer when she replaced her Rolls-Royce Phantom IV with a Silver Shadow. Larkin asked her if she wanted her old numberplate – PM 6450 – transferred to the new car. ‘No,’ she replied. ‘It refers to an incident in my past best forgotten. I want something that doesn’t mean anything.’ Larkin worked out that ‘PM’ stood for Princess Margaret, and ‘6450’ stood for 6 April 1950. What had happened on that day? What was that incident in her past which was ‘best forgotten’? Was it, as some have calculated, the day on which the nineteen-year-old Princess lost her virginity to the Group Captain?

25 (#ubebacbea-06c5-570e-9c15-1d256ab24093)

The romance became public at the Queen’s coronation on 2 June 1953, when Princess Margaret was spotted picking fluff off the Group Captain’s lapel. It was hardly Last Tango in Paris, but in those days interpersonal fluff-picking was a suggestive business. The next morning it was mentioned in the New York papers, but the British press remained silent for another eleven days. The People then printed the headline ‘They Must Deny it NOW’, above photographs of the two of them. ‘It is high time,’ read the front-page editorial, ‘for the British public to be made aware of the fact that scandalous rumours about Princess Margaret are racing around the world.’ The writer then added, perversely, ‘The story is, of course, utterly untrue. It is quite unthinkable that a royal princess, third in line of succession to the throne, should even contemplate a marriage to a man who has been through the divorce courts.’

Within days, the prime minister, the cabinet, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the newspapers and the entire British public had got themselves into a flurry of alarm, delight, concern, horror, approval, dismay, condemnation, joy and despair. Everyone, high and low, had an opinion, for or against. Lascelles himself drove down to Chartwell to inform Winston Churchill of the developing crisis. ‘A pretty kettle of fish’ was the verdict of Churchill’s private secretary, Jock Colville – the very same phrase, incidentally, that Queen Mary had employed seventeen years before, on hearing that her elder son was intent on marrying a double-divorcee from Baltimore. Readers of the Sunday Express turned out to be three-to-one against the union. Mrs M. Rossiter of Whixley, York, declared that ‘I am not one of those who consider a married man with two children suitable for any girl of about 20.’ On the other hand, when the Daily Mirror conducted a readers’ poll, complete with a voting form, of the 700,000 readers who bothered to vote, a full 97 per cent thought that the couple should be allowed to marry.

(Paul Popper/Popperfoto/Getty Images)

Nella Last, who kept a diary for the Mass-Observation archive, noted that ‘My husband was in a dim mood – & Mrs Salisbury [their cleaner] was in one of her most trying. Her disgust & indignation about Princess Margaret being “such a silly little fool” held her up at times … “It’s not nice Mrs Last. I’d belt our Phyllis for acting like that. And a lot of silly girls who copy Princess Margaret’s clothes will think they can just do owt! … And fancy her being a stepmother … And I bet she would miss all the fuss she gets …”’

Churchill agreed to Lascelles’s curiously old-fashioned suggestion that Townsend be posted abroad, out of harm’s way, and so too did Lilibet. And so, on 15 July 1953, Townsend found himself shunted off into exile, to the almost transparently farcical post of air attaché to the British embassy in Brussels. The idea was that in two years’ time Margaret would be twenty-five, and would no longer require the official consent of the monarch, who would thus avoid being compromised. Those with harder hearts argued that absence makes the heart grow weaker, and that two years would be more than enough time for the fairy-tale romance to wither and die.

Townsend was unable to say goodbye, as he had been whisked abroad before the Princess and her mother had returned from their official tour of Rhodesia. For his part, Lascelles was glad to see the back of him: in a letter to a friend he described him as ‘a devilish bad equerry’, sniffily adding that ‘one could not depend on him to order the motor-car at the right time of day, but we always made allowances for his having been three times shot down into the drink in our defence’.

Life has its consolations, even in Belgium. A few months into his involuntary exile, Townsend went ‘by pure chance’ to a horse show in Brussels. There he watched ‘spell-bound, like everyone else, a young girl, Marie-Luce Jamagne, as she flew over the jumps with astonishing grace and dash’. As if in a fairy tale – or rather, a competing fairy tale – the horse fell, and the dashing young girl lay senseless ‘practically at my feet’. Townsend rushed over to her, and was reassured to learn from one of the judges that she would make a full recovery.

At the time she landed at his feet, Marie-Luce was fourteen, a year older than Princess Margaret had been when he first set eyes on her, some eight years before. A friendship grew. Marie-Luce’s parents invited Townsend to their home in Antwerp. It became a safe haven. ‘It was always open to me and in time I became one of the family. That is what I still am today. Marie-Luce, the girl who fell at my feet, has been my wife for the last eighteen years.’

Quite how close had he grown to Marie-Luce by the time he returned to England, a year after his enforced departure? Did he mention her to Princess Margaret when they were briefly reunited in 1954? ‘Our joy at being together again was indescribable,’ he recalls in his autobiography. ‘The long year of waiting, of penance and solitude, seemed to have passed in a twinkling … our feelings for one another had not changed.’ We must take his word for it. By now they had only one more year to go until the Princess’s twenty-fifth birthday, when she would be free to marry without her sister’s consent.

The next year, Townsend returned from his unofficial exile, prompting fresh speculation that marriage bells would soon be ringing. ‘COME ON MARGARET!’ ran the Daily Mirror headline, imploring her to ‘please make up your mind!’

Once again, everybody, high and low, had an opinion on the matter. Harold Macmillan noted, ‘It will be a thousand pities if she does go on with this marriage to a divorced man and not a very suitable match in any case. It cannot aid and may injure the prestige of the Royal Family.’ Mass-Observation’s Nella Last entertained similar misgivings, while her husband was resolutely against the match. ‘Mrs Atkinson came in. She had got me some yeast,’ Mrs Last recorded in her diary. ‘She said idly, “Looks as if you’re going to be right, that Princess Margaret will marry Townsend – seen the paper yet?” We discussed it. We both felt “regret” she couldn’t have married a younger man. Mrs Atkinson too has “principles” about divorce that I lack. We just idly chatted, saying any little thing that came into our minds, for or against the match. I wasn’t prepared for my husband’s wild condemnation or his outburst about my far too easy-going way of looking at things! I poached him an egg for tea.’ By now, the nation as a whole seemed to have swung behind the idea of the marriage. A Gallup poll discovered that 59 per cent approved of it, and 17 per cent disapproved, with the remainder claiming indifference.

On 1 October the new prime minister, Sir Anthony Eden (himself on his second marriage), informed the Princess that it was the view of the cabinet that if she decided to go ahead with the marriage, she would have to renounce her royal rights, and forgo her income.

Townsend and Margaret were reunited once more on the evening of 13 October. ‘Time had not staled our accustomed, sweet familiarity,’ Townsend recalled, fancily. But after a fortnight of press attention, things no longer seemed quite so straightforward. ‘We felt mute and numbed at the centre of this maelstrom.’

Ten days later, the Princess went to lunch at Windsor Castle with her sister, her mother and the Duke of Edinburgh. According to the Queen’s well-connected biographer Sarah Bradford, the Queen Mother grew tremendously steamed up, declaring that Margaret ‘hadn’t even thought where they were going to live’. Prince Philip, ‘with heavy sarcasm’, replied that it was ‘still possible, even nowadays, to buy a house’. At this, the Queen Mother ‘left the room, angrily slamming the door’.

Towards the end of his life, Lord Charteris* (#ulink_ad64034d-7a7a-58e5-823f-01d99591bbdd) voiced misgivings about the Queen Mother’s behaviour throughout the Townsend affair. ‘She was not a mother to her child. When the Princess attempted to broach the subject her mother grew upset, and refused to discuss it.’

After this fraught lunch, the imperilled couple spoke on the phone. The Princess was, according to Townsend, ‘in great distress. She did not say what had passed between herself and her sister and brother-in-law. But, doubtless, the stern truth was dawning on her.’

The following day, The Times ran an editorial arguing against the marriage, on the grounds that the Royal Family was a symbol and reflection of its subjects’ better selves; vast numbers of these people could never be persuaded that marriage to a divorced man was any different from living in sin. Townsend himself regarded this argument as ‘specious’, and would never have allowed it to sway him. But, he claimed, ‘my mind was made up before I read it’.

That afternoon, he ‘grabbed a piece of paper and a pencil’, and ‘with clarity and fluency’ began to write a statement for the Princess. ‘I have decided not to marry Group Captain Townsend,’ it began. With that, he went round to Clarence House and showed her the rough piece of paper. ‘That’s exactly how I feel,’ she said.

‘Our love story had started with those words,’ he recalled in old age. ‘Now, with the same sweet phrase, we wrote finis to it … We both had a feeling of unimaginable relief. We were liberated at last from this monstrous problem.’

* (#ulink_1c883d11-a31d-5585-b3c1-92c80ac2d418) 1913–99. Assistant private secretary to HM Queen Elizabeth II, later private secretary, and later still Provost of Eton. Aged eighty-one, and imagining he was speaking off the record, he gave an interview to the Spectator in which he called the Queen Mother ‘a bit of an ostrich’, the Prince of Wales ‘such a charming man when he isn’t being whiny’, and, most memorably, the Duchess of York ‘a vulgarian, vulgar, vulgar, vulgar’.

26 (#ubebacbea-06c5-570e-9c15-1d256ab24093)

How does a fairy-tale romance turn into a monstrous problem? ‘I had offended the Establishment by falling in love with the Queen’s sister,’ was the Group Captain’s simple explanation. But was it sufficient?

In Time and Chance, Townsend declares that ‘It was practically certain that the British and Dominions parliaments would agree – but on condition that Princess Margaret was stripped of her royal rights and prerogatives, which included accession to the throne, her royal functions and a £15,000 government stipend due on marriage – conditions which, frankly, would have ruined her. There would be nothing left – except me, and I hardly possessed the weight to compensate for the loss of her privy purse and prestige. It was too much to ask of her, too much for her to give. We should be left with nothing but our devotion to face the world.’

When Time and Chance was published in 1978, it enjoyed a largely respectful reception, most critics commending the tact with which its author covered his relationship with Princess Margaret. ‘Balanced and charitable’, read a typical review.

But one critic broke ranks. Alastair Forbes was a cousin of President Roosevelt, the uncle of the future US secretary of state John Kerry, and a friend of the well-connected, among them Cyril Connolly, Randolph Churchill, the Grand Duke Vladimir of Russia, the Duke and Duchess of Kent, and Prince and Princess Paul of Yugoslavia. He was, however, seen as trouble by some of the more prominent royal households: Princess Margaret used to refer to him as ‘that awful Ali Forbes’, while Queen Elizabeth II was once heard to yell, ‘Will you please put me DOWN!’ as he lifted her up during a Highland reel.

Like many of the most energetic stately-home guests, he traded in gossip, usually about those with whom he had just been staying. His fruity tales were peppered with nicknames, often based around puns. For instance, he retitled Temple de la Gloire, Oswald and Diana Mosley’s home outside Paris, ‘The Concentration of Camp’; Essex House, the home of James and Alvilde Lees-Milne, became ‘Bisex House’.

Forbes was long rumoured to be some sort of non-specific spy, either for the CIA or MI6, or possibly both at the same time. His whole life was to some extent swathed in mystery, much of it of his own making. Sustained by a private income, he dabbled in politics and journalism and, in his sixties, took to reviewing books for the Times Literary Supplement and the Spectator. His prose had a Firbankian quality, its long, elegantly rambling sentences choc-a-bloc with foreign phrases, ribald asides, Byzantine names, incautious allegations and forensic examinations of abstruse questions such as ‘Did the Duke of Windsor have pubic hair?’

He had a morbid side to his character. At funerals, some detected an air of triumph emanating from him as friends, enemies and chance acquaintances were lowered into the soil. He was also something of an early bird at deathbeds, pen at the ready to transcribe any last words. It was death that brought his competitive streak to the surface: he had, for instance, made it his mission to be the last man to see Diana Cooper alive.* (#litres_trial_promo)

Forbes was an egalitarian, in that he was as rude to the highest-born as to the lowest. Perhaps more so: he once dismissed Jesus Christ’s Sermon on the Mount as being on a par with the mottoes contained in Christmas crackers. His review of Peter Townsend’s autobiography, published under the heading ‘The Princess and the Peabrain’, followed this cock-snooking impulse. Throughout the piece he portrayed Townsend as an upstart – ‘What might be pardonable as the dream of an assistant housemaid was entirely unsuitable for an assistant Master of the Household’ – and his memoir as yet another attempt to cover the tracks of his social climbing. Rejecting the Townsend version of himself as a victim of love and circumstance, Forbes poured scorn over his every excuse and explanation:

‘How to consummate this mutual pleasure was the problem,’ writes the author in his best Monsieur Jordain style. You don’t say! His imagination, he adds, never at a loss for a cliché, ‘boggled at the prospect of my becoming a member of the Royal Family’. Boggled perhaps, but no more than it had been Mittyishly boggling away on the back burner for years. ‘All we could hope was that with time and patience, some solution might evolve.’ Meanwhile, he neither felt the slightest conscientious compulsion to resign from a position whose trust he had so weakly betrayed, his perverted taste for risk overcoming his sense of duty and gratitude to his Royal employers of eight years, nor did he feel able to say, after the fashion of those pretty inscribed Battersea enamel boxes: ‘I love too well to kiss and tell.’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: