По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

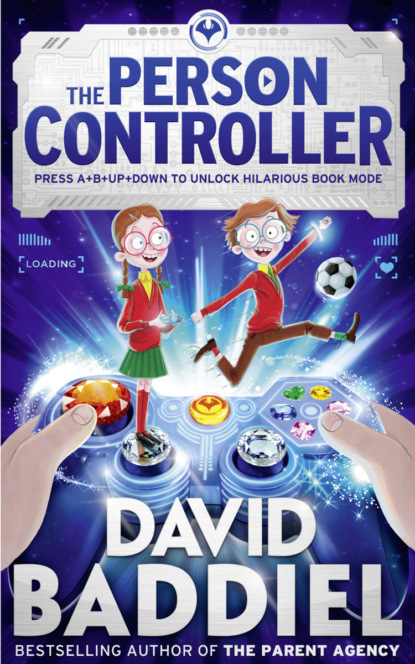

The Person Controller

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Fred looked away, embarrassed.

Even though he didn’t mind at all that his sister was better than him at video games, he did mind people at school making fun of him for it. Which some did. Not because Ellie had told everyone, but because Eric, at Bracket Wood’s last parent-teacher evening, when asked by their form teacher, Miss Parr, what he thought Ellie’s particular talents were, had said: “Video games. You’d have thought that would’ve been the boy, but no, she’s the one with the magic fingers!!”

Unfortunately, Eric’s voice was very loud and booming, and everyone in their form room – and most of the rest of the school – had heard.

“In fact, Fred, you’re probably even worse at video games than you are at actual games!” said Isla.

“Yeah! Actual games!” said Morris.

“Like …” said Isla, turning to Morris.

There was a pause.

“What?” said Morris.

“I thought you might say this bit,” said Isla.

Morris frowned. “What bit?”

“The bit about which games he’s rubbish at …? Like, give some examples?”

Morris looked blank.

“Oh, come on, Morris!” said Isla. “Do you have any idea how hard it is to always drive the bullying? To have to come up with all the clever things to say to humiliate other children? Frankly, I’m starting to think you’re just a passenger in what we’re doing here.”

Morris frowned again. Then he frowned some more. Finally, his face cleared. “Football!” he said, clicking his fingers.

“Yes! Well done, Morris! Yeah! What are you worse at, Fred – FIFA or football? You could hardly be worse at FIFA – because I’ve never seen anyone so bad at football!”

“Yeah, so bad at football!” said Morris.

“Oh, shut up!” said Ellie, getting up to face the bullies.

“Yeah, shut up!” said Fred, getting up and facing them too. He had had enough.

Because football meant a lot to Fred. He wanted more than anything to be in the Bracket Wood First XI. He wanted to be in the Bracket Wood First XI and score the winning goal in the final of the Bracket Wood and Surrounding Area Inter-school Winter Trophy. Ever since he was old enough, he had gone to the school trials for the team. And every year he hadn’t got in. Every year something had gone wrong.

Let’s just take a moment out from the main story to look at the last time Fred went to one of the trials for the school football team.

(#ulink_b22f9d64-e13a-5831-b676-e19dbc9619b5)

This was last year, when Fred was in Year Five. For the trial, Fred had spent all his pocket money on a new pair of football boots. Bright yellow ones. Marauders. Fred was totally convinced that they were going to make all the difference (to the fact that he hadn’t been picked on any of the three preceding years).

Unfortunately, Eric and Janine had never taught Fred how to tie his shoelaces properly.

So what normally happened was that every morning, before school, Ellie would tie Fred’s school shoes very, very tightly with a triple bow. And that would be fine; they would stay tied for the whole day.

But, before the school team trial, Fred had asked Ellie to tie his Marauders with just a single bow. Because a triple bow, he thought, would be too bulky and make it very difficult – for example – when the ball came to him on the edge of the penalty area to bend it round five defenders into the top right-hand corner (not something he had ever done, but he was sure he was going to this time).

“Really?” said Ellie, kneeling down by the touchline of the school pitch. I say school pitch. And touchline. Bracket Wood was a good school – more or less – but its school pitch was a muddy triangle in the local park and its touchline was the concrete path around it.

“Really,” said Fred. “A single knot.” And ran on. And, as his laces came untied, tripped over. Into some mud.

And then ran backwards and forwards to the touchline throughout the game so that Ellie could retie his shoelaces.

He did stop doing that eventually. Because, after the fifth time, Ellie said: “If you’re not going to let me tie a triple knot, I’m not tying them at all any more!!” and went to sit on the roundabout in the playground six metres away.

After which Fred had to ask the referee, Mr Barrington, to tie his shoelaces. Bracket Wood was a good school – more or less – but its sports teacher was Mr Barrington, who was sixty-seven and wore glasses with lenses thicker than a rhinoceros’s foot.

So after Mr Barrington had sighed very heavily and bent down on one knee in the mud to tie up Fred’s shoelaces – and after it had taken him three minutes to get up again, during which time four goals were scored that never got recorded – he made a point of running (well, staggering) away every time Fred approached him.

Fred didn’t know what to do. His boots kept on coming off. Briefly, he even wished his mum or dad was there, which was something he didn’t often wish for.

Then, eventually, Ellie came back from the playground and Fred let her tie the Marauder shoelaces into a triple bow. Two minutes later, the ball came to him on the edge of the penalty area.

“Come on, Fred!” shouted Ellie. “Hit it!”

Fred focused on the ball. He ran towards it, confident now that his shoelaces were not going to come undone. He hit the ball square in the middle of his left boot.

Square in the middle of his triple bow.

So the ball went almost nowhere near his actual foot. It went almost entirely near the big knot of his shoelace. Fred, to be fair, had been right. A bow that size was too bulky. Which wasn’t much comfort to him as the ball spun backwards over his head, hitting Mr Barrington full in the face. “Ow!!!” said Mr Barrington, as his rhino-foot-lens glasses flew off his face and into the mud.

Everyone apart from Fred laughed, loud and long. Fred himself just turned and walked off, knowing that he certainly wasn’t going to get into the school team this time.

Now let’s go back to the main story.

(#ulink_3b808e55-885e-5326-b86d-384db07c97ff)

So that’s why Isla and Morris making fun of his footballing ability did touch a nerve with Fred. And why he told them to shut up.

It felt good, saying shut up. It felt, to Fred, that the time had come to stand up and be counted, and he had stood up and been counted. He had said: This much and no more. He had drawn a line in the sand and told the bullies not to cross it.

And that feeling – that he had stood up and been counted, that he had said this much and no more, that he had drawn a line in the sand and told the bullies not to cross it – was certainly some small comfort to Fred as Morris proceeded to give him a dead leg, an elbow drill and a wedgie.

(#ulink_01dc56ea-287d-5a16-a96d-d1dee2da65d8)

“I feel really bad,” said Ellie, trying to help Fred out of the dustbin. (Isla and Morris’s last move, a classic bit of bullying, was to plonk Fred in the computer-room bin bottom first, so that his legs stuck out like wheelbarrow handles.)

“Don’t feel really bad,” said Fred.

“What did you say?” said Ellie.

“I said …” said Fred, trying hard this time not to groan as he said it, “don’t feel really bad.”

“But I’m your sister.” She grabbed hold of his legs and pulled. “And just because I’m a girl shouldn’t mean that I can’t protect you from the bullies and …”

As she spoke, her weight finally pulled her brother – and the bin attached to his bum, looking not unlike a snail’s shell – forward. Two seconds later, the bin clattered to the floor, popping Fred out as it went. He picked himself up.