По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

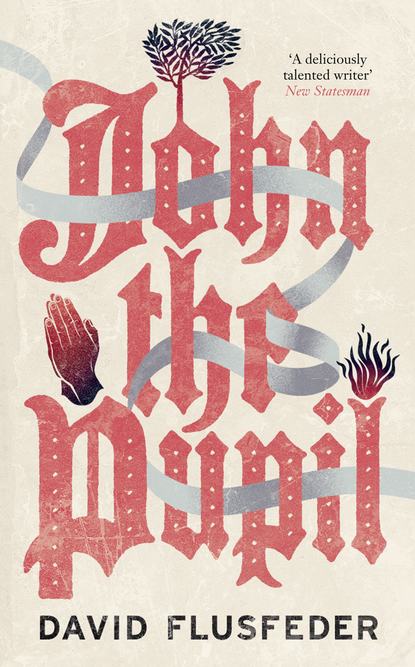

John the Pupil

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

What is in your bag? the man said. Treasures, I expect.

None that you would recognise, I said.

We will not pay, Brother Bernard said.

Then you will not pass, the man said.

Brother Bernard lifted the man away from the ground as if he was shaking a fallen leaf, and coins rolled out of his scrip, and the throng at first did not know how to respond to this turn of events. But when Brother Bernard had hurled the man into one of the guards with the staves, and was already moving to the other, who hesitated, as if he could not decide whether to set upon him or flee, members of the crowd were scratching around on the ground for the fallen coins, and Brother Bernard was advancing upon the second guard, who made his decision, to flee, and we watched him run, and then Brother Bernard said, in his usual tone of plain announcement,

We should go on.

We went on.

In Rule Three of our Order, the blessed Saint Francis counsels, admonishes and begs his brothers that when we travel about the world, we should not be disputatious, contend with words, or criticise others, but rather should be gentle, peaceful and unassuming, courteous and humble, speaking respectfully to all as is due. Behold, he says, I send you as a sheep in the midst of wolves. Be therefore wise as serpents and as simple as doves.

Of the three of us, only Brother Andrew’s behaviour in the matter of the toll men was without sin. The Cathedral rose above us, as we made our slow process towards it through elbows and shoulders of pilgrims, and Brother Bernard denied that he had behaved improperly.

It was right, he said.

When Brother Bernard takes a position he is unyielding.

Those men were demons, he said.

We must give greater penance, I said.

You do as your conscience tells you and I shall do likewise, he said.

I had not been prepared for such multitudes. Brother Andrew thrust himself for safety between me and Brother Bernard. We were the sick, we were lepers and cripples, madmen, peasants, noblemen, pilgrims, all come to visit the relics of the saint. Beggars outside, preaching monks, merchants selling badges of the shrine.

Guard your bags, said a kindly-looking man on my left.

I carry three bags across my shoulders. In one are the necessities for my journey. In the second is space for the treasures I am to gather along the way, and the package my Master gave me that is only to be opened when we meet despair. The third bag is the scrip in which I carry my Master’s Great Work. Alerted by the kindly man’s warning, my hand went immediately to the third bag. I felt no stranger’s hand, the seal was untouched.

There are cutpurses everywhere, the kindly man said.

He was not a monk, and nor was he a nobleman, because his costume was ragged and worn. He looked like someone who worked on the land, but a labourer on the land would not have spoken in Latin. His tunic was extraordinary: on the worn thread were pinned dozens of lead badges in the shape of saints and stars.

Even here?

Especially here. You have not been to Canterbury before?

We have been to nowhere before.

They call me Simeon the Palmer.

I am John the Pupil. My companions are Brother Bernard and Brother Andrew.

You are making penance?

This was the first encounter I had had on my journey in which I felt greeted with tenderness. There was something about Simeon the Palmer, his wise eyes, the steadiness of his hand on my arm, his odour of violets, that made me yearn to tell him about my childhood and my father’s goats and life in the friary and my loneliness and my learning, and my mission and my Master, so that he should know to love him as much as I do.

We are making pilgrimage.

As am I. I go to Rome and then Compostela and on to the Holy Land.

You must carry a heavy burden of sins.

Most of them are not my own.

As we processed to the Cathedral gate, Simeon the Palmer explained to me that his occupation is to make pilgrimage on behalf of men who have a weight of sins, the desire to expiate them, and the money to pay someone else to do so on their behalf.

You make the pilgrimage and you perform the penance and your hirer stays at home and the consequence is that he is shrived?

That is how it works.

The world is a strange place.

Simeon the Palmer offered to make penance for us. You could divest your load on to me, he said.

I had not been prepared for the magnificence of the Cathedral, the glory of it, its size, the frescoes on the walls, the holy blaze of the windows. Brother Andrew and I made confession and washed our hands and the three of us were directed towards the foot of the stairs up to the martyr’s shrine, where we removed our shoes and joined the procession of those who have been afflicted, by deformity or disease or riches, because we are all equal in sin.

We kissed the floor, we climbed the stairs on our hands and knees. A registrar sat with a book of miracles beside the shrine. Two Cathedral monks stood watch over the pile of jewels and money left by previous penitents. We had nothing to offer except our devotion and humility. Master Roger warns that men devoting themselves to holiness must try to avoid the short direct rays emanating from delectable things, such as women and food and riches. Prostrate at the martyr’s shrine, I thought I detected an avaricious shine in Brother Bernard’s eyes, a hungry vacuity mirroring the glistening of the jewels.

After we climbed back down and reclaimed our shoes and received the blessing for our pilgrimage, we were outside the Cathedral gate again and Simeon the Palmer was with us, pinning a new badge on to his tunic.

Paradise knocks on your door, a beggar said holding out his hand towards us, but seeing the look in Brother Bernard’s eyes he quickly withdrew it again and turned his attention to other pilgrims.

My Master has placed a lonely burden on me. My companions believe that this is a pilgrimage of penance, so that is what it will have to be, for sins of pride and avarice and concupiscence. They do not know the purpose of our journey.

Saint Germanus’s Day

Germanus began every meal by swallowing ashes. He never ate wheat or vegetables, drank no wine and did not flavour his food with salt. Germanus gave all his wealth away to the poor, lived with his wife as brother and sister, and for thirty years subjected his body to the strictest austerity. He spread ashes on his bed, whose only covering was a hair shirt and a sack. Such was his life that if there had not been any ensuing miracles, and there were many miracles, his holiness alone would have admitted him to the order of the saints.

•

I related the life and miracles of Saint Germanus and we stood by the boats at Dover with hands outstretched. Paradise knocks on your door, Brother Bernard said. Brother Andrew is not yet used to mendicancy. He was shy, his eyes downcast, his cheeks reddening. All the same, it was he who received the greatest alms. A pious captain gave us passage on his boat, in exchange for our consenting to lead a service after the boat had got under way, and a promise not to impede or obstruct or beg from the passengers and crew.

Brother Andrew stood on the prow as we waited for the boat to take to sea. Brother Bernard, who shows an aversion to water, sat in the stern wrapped inside his cloak. Brother Andrew and I watched the passengers climb on board, the pilgrims and merchants, and a great lord, whose passage demanded a retinue of servants and the transport of a score of horses, and carts overlaid with barehide, their wheels bound with iron, and boxes made of iron and wood, and barrels of wood, and bags made of leather and canvas.

The lord’s chamberlain oversaw the loading of his master’s goods. He was a man of powerful build, who roared out orders to his underlings who followed his instructions as if on pains for their lives.

They are like soldiers obeying their general, I said to Brother Bernard, trying to rouse him from his dolour.

When did you ever see a soldier? Brother Bernard said.

It is true. I have never seen a soldier, or a lion, or a feast on a great man’s table, or a demon or an angel or a nun or a unicorn or a bride or a Jew. But before I set out on this journey I had never seen a cathedral or a man who made a living expiating other men’s sins, and neither had I seen a great lord. This one was a man of small stature and sharp visage. He watched his chamberlain issuing the orders and drank from a small flask.

Maybe it was this, the possibility of all things now that I am upon this journey, or maybe it was the sight of Brother Andrew stretched forward on the prow, his arms fully extended, his body leaning into the breeze, or maybe it was the gentle motion of the boat rocking beneath me, that I felt touched by something forgotten from long ago, and was suddenly lifted, exhilarated, incorporeal, yet alive with the acuity of my senses.