По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

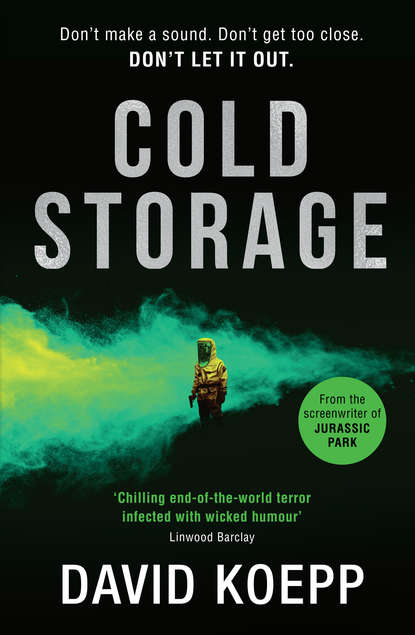

Cold Storage

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Hero thought about that for a second. “Good question.” She opened the file on the table in front of her and started talking.

Six hours later, she stopped.

WHAT ROBERTO KNEW ABOUT WESTERN AUSTRALIA COULD FIT INTO A very small book. More of a flyer, really: one page and with large type. Hero told them they were going to a remote township called Kiwirrkurra Community, in the middle of the Gibson Desert, about 1,200 kilometers east of Port Hedland. It had been established a decade earlier as a Pintupi outstation, part of the Australian government’s ongoing attempts to allow and encourage Aboriginal groups to move back to their traditional ancestral lands. They’d been mistreated and cleared out of those same territories for decades, most recently in the 1960s as a result of the Blue Streak missile tests. You can’t very well be living on land that we want to blow up. It’s unhealthy.

But by the midseventies the tests were over, political sensitivities were on the rise, and so the last of the Pintupi had been trucked back to Kiwirrkurra, which wasn’t even the middle of nowhere, but more like a few hundred miles outside the very outer rim of nowhere. But there they lived, all twenty-six Pintupi, as peaceful and happy as human beings can be in a stifling desert without power, telephone lines, or any connection to modern society. They rather liked being cut off, in fact, and the elders in particular were pleased with their return to their ancestral lands.

And then the sky fell.

Not all of it, Hero explained. Just a chunk.

“What was it?” Roberto asked. He’d been holding eye contact with her throughout the brief history so far, and don’t think for a second Trini didn’t notice. In fact, she was glaring at Roberto, as if psychically willing him to stop.

“Skylab.”

Now Trini turned her head and looked at Hero. “This was in ’79?”

“Yes.”

“I thought that fell into the Indian Ocean.”

Hero nodded. “Most of it did. The few pieces that hit land fell just outside a town called Esperance, also in Western Australia.”

“Close to Kiwirrkurra?” Roberto asked.

“Nothing is close to Kiwirrkurra. Esperance is about two thousand kilometers away and has ten thousand residents. It’s a metropolis by comparison.”

“What happened to the pieces that fell in Esperance?”

Hero turned to the next section of her notes. The pieces that fell in Esperance had been, rather enterprisingly, scooped up by the locals and put in the town’s museum—formerly a dance hall, but quickly converted to the Esperance Municipal Museum & Skylab Observatorium. Admission was four dollars, and for that you could see the largest oxygen tank from the orbiter, the space station’s storage freezer for food and other items, some nitrogen spheres used by its attitude control thrusters, and a piece of the hatch the astronauts would have crawled through during their visits. A number of other chunks of unrecognizable debris were also put on view, including a piece of sheet metal that rather suspiciously had the word SKYLAB neatly lettered in undamaged bright red paint across its middle.

“For years NASA assumed that was all that would ever be found, as the rest of it either burned up on re-entry or is at the bottom of the Indian Ocean,” Hero continued. “After five or six years, they figured anything else on land would have turned up by then or was somewhere uninhabitable.”

“Like Kiwirrkurra,” Roberto offered.

She nodded and turned another page.

“Three days ago, I got a call from the NASA Space Biosciences Research Branch. They’d gotten a message, relayed through about six different government agencies, that someone was calling from Western Australia because ‘something had come out of the tank.’”

“What tank?”

“The extra oxygen tank. The one that fell on Kiwirrkurra.”

Trini sat forward. “Who called from Western Australia?”

Hero looked down at her notes. “He identified himself as Enos Namatjira. He said he lived in Kiwirrkurra and his uncle had found the tank in the dirt five or six years earlier. Uncle had heard about the spaceship that crashed, so he moved it in front of his house and kept it there as a souvenir. But now there was something wrong with it, and he was getting sick. Quickly.”

Roberto frowned, trying to piece it together. “How did this guy know what number to call?”

“He didn’t. He started with the White House.”

“And it got through to NASA?” Trini was incredulous. Such efficiency was unheard of.

“It took him seventeen calls, and he had to drive thirty miles to get to the phone every time, but yes, he finally got through to NASA.”

“He was determined,” Roberto said.

“He was, because by that time, people were dying. They finally put him in touch with me about a day and a half ago. I do work for NASA sometimes, inspecting their re-entry vehicles to make sure they’re clear of any foreign bioforms, which they always are.”

“But you think this time something came back?” Trini asked.

“Not quite. This is where it gets interesting.”

Roberto leaned forward. “I think it’s pretty interesting already.”

Hero smiled at him. Trini tried not to roll her eyes.

Hero continued. “The tank was sealed, and I highly doubt that it could bring anything back from space that it wasn’t sent up with. I went through all the Skylab files, and on the last resupply it seems this particular oxygen tank had been sent up not for O

circulation, but solely for attachment to one of the outer pod arms. There was a fungal organism inside the tank, a sort of cousin of Ophiocordyceps unilateralis. It’s a cool little parasitic fungus that can adapt from one species to another. Known to survive extreme conditions, a bit like Clostridium difficile spores. You know those?”

They looked at her blankly. Knowledge of Clostridium difficile was not a requirement in their line of work.

“Well, they’re pernicious. They can survive anywhere—inside a volcano, bottom of the sea, outer space.”

They just looked at her, taking her word for it. She went on. “Anyway. The sample in the tank was part of a research project. The fungus had some peculiar growth properties and they wanted to see how it was affected by conditions in space. Remember, it was the seventies, orbital space stations were going to be the next big thing, so they needed to develop effective antifungal medications for the millions of people who were going to go live up there. But they never got the chance.”

“Because Skylab crashed.”

“Right. So, after five or six years sitting outside in front of Enos Namatjira’s uncle’s house, the tank started to rust. Uncle wanted to spruce it up a little bit, make it shiny and new again, maybe people would pay to come see it. He tried to remove the rust, but it was resistant. According to Enos, his uncle tried a number of different cleaners, finally using a folkloric solution: cutting a potato in half, pouring dish soap on it, and rubbing it on the surface of the tank.”

“Did it work?”

“Yep. The rust came off easily, and the thing shined up. A few days later, Uncle got sick. He started to behave erratically, not making a great deal of sense. He climbed onto the roof of his house and refused to come down, and then his body started to swell uncontrollably.”

“What the hell happened?” Trini asked.

“From this point forward, everything I say is hypothesis.”

She paused. They waited. Whether Dr. Martins was aware of it or not, she knew how to tell a story. They were transfixed.

“I believe the chemical combination that Uncle used dripped through microfissures in the tank’s exterior and landed inside, where the dormant Cordyceps fungus was rehydrated.”

“With the potato stuff?” Roberto wondered. Didn’t sound very hydrating.

She nodded. “The average potato is seventy-eight percent water. But the fungus wasn’t just rehydrated; it was given pectin, cellulose, protein, and fat. And a nice place to grow. The average temperature in the Western Australian desert at this time of year is well over a hundred degrees Fahrenheit. Inside the tank, it’s probably closer to a hundred thirty. Deadly for us, but perfect for a fungus.”

Trini wanted to get to the point. “So, you’re saying the thing came back to life?”