По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

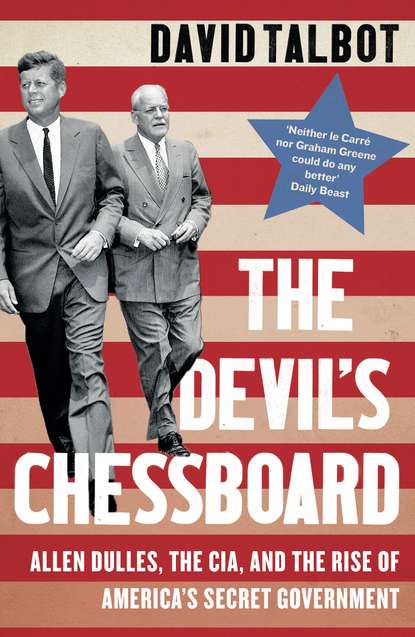

The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Like Dulles, McKittrick was not popular with Roosevelt and his inner circle. FDR’s Treasury secretary, Henry Morgenthau Jr., developed a deep loathing for McKittrick, whom Morgenthau’s aide, Harry Dexter White, called “an American [bank] president doing business with the Germans (#litres_trial_promo) while our American boys are fighting the Germans.” The Roosevelt administration moved to block BIS funds in the United States, but McKittrick hired Foster Dulles as legal counsel, who successfully intervened on the bank’s behalf.

Morgenthau was outraged when McKittrick made a business trip to the United States in winter 1942 and was warmly feted by Wall Street. Dozens of powerful financiers and industrialists—including the executives of several corporations, such as General Motors and Standard Oil, that had profited handsomely from doing business with the Nazis—gathered for a banquet in McKittrick’s honor at New York’s University Club on December 17.

Morgenthau tried to prevent McKittrick from returning to BIS headquarters in Switzerland on the grounds that the bank was clearly aiding the Nazi war effort. The banker later sniffed about the “nasty crew in the Treasury (#litres_trial_promo) at the time … I was very suspect because I talked to Italians and talked to Germans—and I said that they had behaved very well. I [refused to denounce them as] villains of the worst sort.” Allen Dulles came to McKittrick’s rescue, deftly pulling strings on the banker’s behalf, and in April 1943 he finally boarded a transatlantic flight to Europe.

Dulles and McKittrick continued to work closely together for the rest of the war. In the final months of the conflict, the two men collaborated against a Roosevelt operation called Project Safehaven that sought to track down (#litres_trial_promo) and confiscate Nazi assets that were stashed in neutral countries. Administration officials feared that, by hiding their ill-gotten wealth, members of the German elite planned to bide their time after the war and would then try to regain power. Morgenthau’s Treasury Department team, which spearheaded Project Safehaven, reached out to the OSS and BIS for assistance. But Dulles and McKittrick were more inclined to protect their clients’ interests. Moreover, like many in the upper echelons of U.S. finance and national security, Dulles believed that a good number of these powerful German figures should be returned to postwar power, to ensure that Germany would be a strong bulwark against the Soviet Union. And during the Cold War, he would be more intent on using Nazi loot to finance covert anti-Soviet operations than on returning it to the families of Hitler’s victims.

Dulles realized that none of his arguments against Project Safehaven would be well received by Morgenthau. So he resorted to time-honored methods of bureaucratic stalling and sabotage to help sink the operation, explaining in a December 1944 memo to his OSS superiors that his Bern office lacked “adequate personnel (#litres_trial_promo) to do [an] effective job in this field and meet other demands.”

McKittrick demonstrated equal disdain for the project, and his lack of cooperation proved particularly damaging to the operation, since BIS was the main conduit for the passage of Nazi gold. “The Treasury [Department] kept sending sleuth hounds (#litres_trial_promo) over to Switzerland,” he complained years later. “The only thing they were interested in was where was Hitler putting his money, and where [Hermann] Goering was putting his money, and [Heinrich] Himmler, and all the rest of the big boys in Germany. But I, myself, am convinced that those fellows were not piling up money for the future.”

While Allen Dulles was using his OSS post in Switzerland to protect the interests of Sullivan and Cromwell’s German clients, his brother Foster was doing the same in New York. By playing an intricate corporate shell game (#litres_trial_promo), Foster was able to hide the U.S. assets of major German cartels like IG Farben and Merck KGaA, the chemical and pharmaceutical giant, and protect these subsidiaries from being confiscated by the federal government as alien property. Some of Foster’s legal origami allowed the Nazi regime to create bottlenecks in the production of essential war materials—such as diesel-fuel injection motors that the U.S. military needed for trucks, submarines, and airplanes. By the end of the war, many of Foster’s clients were under investigation by the Justice Department’s antitrust division. And Foster himself was under scrutiny for collaboration with the enemy.

But Foster’s brother was guarding his back. From his frontline position in Europe, Allen was well placed to destroy incriminating evidence and to block any investigations that threatened the two brothers and their law firm. “Shredding of captured Nazi (#litres_trial_promo) records was the favorite tactic of Dulles and his [associates] who stayed behind to help run the occupation of postwar Germany,” observed Nazi hunter John Loftus, who pored through numerous war documents related to the Dulles brothers when he served as a U.S. prosecutor in the Justice Department under President Jimmy Carter.

If their powerful enemy in the White House had survived the war, the Dulles brothers would likely have faced serious criminal charges for their wartime activities. Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, who as a young lawyer served with Allen in the OSS, later declared that both Dulleses were guilty of treason.

But with Franklin Roosevelt gone from the arena, as of April 1945, there was not enough political will to challenge two such imposing pillars of the American establishment. Allen was acutely aware that knowledge was power, and he would use his control of the country’s rapidly expanding postwar intelligence apparatus to carefully manage the flow of information about him and his brother.

FDR announced the Allied doctrine of “unconditional surrender” at the Casablanca Conference with British prime minister Winston Churchill in January 1943. The alliance’s third major leader, Soviet premier Joseph Stalin, was unable to attend the conference because he was still contending with the horrific Nazi siege of Stalingrad. The Red Army would finally prevail at the Battle of Stalingrad, and the epic victory shifted the war’s momentum against the Third Reich. But the costs were monumental. The Soviet Union lost over one million soldiers during the struggle for Stalingrad—more than the United States would lose during the entire war.

The Casablanca Conference, held January 12–23, 1943, at a barbed wire–encircled hotel in Morocco, would sorely aggrieve the missing Russian leader by concluding that it was too soon to open a second major front in France. But Roosevelt’s unconditional surrender declaration, which took Churchill by surprise, was FDR’s way of reassuring Stalin that the Americans and British would not sell out the Soviet Union by cutting a separate peace deal with Nazi leaders.

The Casablanca Conference was a major turning point in the war, sealing the fate of Hitler and his inner circle. As Roosevelt told the American people in a radio address following the conference, by taking an uncompromising stand against the Third Reich, the Allies made clear that they would not allow Hitler’s regime to divide the antifascist alliance or to escape justice for its monumental crimes. “In our uncompromising policy (#litres_trial_promo),” said Roosevelt, “we mean no harm to the common people of the Axis nations. But we do mean to impose punishment and retribution in full upon their guilty, barbaric leaders.”

With his close ties to Germany’s upper echelons, Dulles considered the unconditional surrender declaration a “disaster” and was quick to let his Nazi contacts know what he thought about it. Shortly after the Casablanca Conference, Dulles sat down one wintry evening with an agent of SS leader Heinrich Himmler, an oily Mittel-European aristocrat who had flitted in and out of Dulles’s social circle for many years. Dulles received his guest, who was known as “the Nazi prince,” at 23 Herrengasse, treating him to good Scotch in a drawing room warmed by a fire. The Casablanca Declaration had clearly unnerved Himmler’s circle by making it clear that there would be no escape for the Reich’s “barbaric leaders.” But Dulles took pains to put his guest’s mind at rest. The Allies’ declaration, Dulles assured him, was “merely a piece of paper (#litres_trial_promo) to be scrapped without further ado if Germany would sue for peace.”

Thus began Allen Dulles’s reign of treason as America’s top spy in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Maximilian Egon von Hohenlohe, the Nazi prince, was a creature of Europe’s war-ravaged landed aristocracy. Prince Max and his wife, a Basque marquesa, had once presided over an empire of properties stretching from Bohemia to Mexico. But two world wars and global economic collapse had stripped Hohenlohe of his holdings and reduced him to playing the role of Nazi courier. The prince had first met Dulles in Vienna in 1916, when they were both young men trying to make a name for themselves in diplomatic circles. During the 1930s, after he fell into the less refined company of the SS thugs who had taken over Germany, Hohenlohe popped up as an occasional guest of Allen and Clover in New York.

Hohenlohe was just one more member of the titled set who saw advantages to Hitler’s rise, and was quite willing to overlook its unpleasant side, which the prince explained away as rank-and-file Nazi Party excesses that would inevitably be sorted out. The Hohenlohe family was filled with ardent Nazi admirers. Perhaps the most bizarre was Stephanie von Hohenlohe (#litres_trial_promo), who became known as “Hitler’s princess.” A Jew by birth, Stephanie found social position by marrying another Hohenlohe prince. In the years before the war, she became one of Hitler’s most tireless promoters, helping to bring British press magnate Lord Rothermere into the Nazi fold. Stephanie took Hitler’s handsome, square-jawed adjutant Fritz Wiedemann as a lover and laid big plans for their rise to the top of the Nazi hierarchy. But it was not to be. Jealous of her favored position with Hitler, SS rivals plotted against her, spreading stories about her Jewish origins. Her aunt died in a concentration camp, and Stephanie was forced to flee Germany.

But Prince Max suffered no such fall from grace. He roamed Europe, feeling out British and American diplomats on a possible deal that would sacrifice Hitler but salvage the Reich. Wherever he went, Hohenlohe got a brusque reception. British foreign secretary Anthony Eden warned against even speaking with the prince: “If news of such a meeting (#litres_trial_promo)became public … the damage would far exceed the value of anything the prince could possibly say.” American diplomats in Madrid, who were also approached by Hohenlohe, dismissed him as a “flagrant” liar (#litres_trial_promo) and a “totally unscrupulous” schemer whose overriding concern was “to protect his considerable fortune.”

Dulles brushed aside these concerns; he had no compunctions about meeting with his old friend. The truth is, he felt perfectly at ease in the company of such people. Before the war, Dulles had been an occasional guest of Lord and Lady Astor at Cliveden, the posh couple’s country home along the Thames that became notorious as a weekend retreat for the pro-Nazi aristocracy. (There is no getting around this unwelcome fact: Hitler was much more fashionable in the social settings that men like Dulles frequented—in England as well as the United States—than it was later comfortable to admit.)

Royall Tyler (#litres_trial_promo), the go-between who set up the Bern reunion between Dulles and Hohenlohe, was cut from similar cloth. Born into Boston wealth, Tyler traipsed around Europe for most of his life, collecting Byzantine art, marrying a Florentine contessa, and playing the market. The multilingual Tyler and his titled wife led a richly cultured life, with Tyler haunting antique shops and private collections in search of Byzantine treasures and restoring a château in Burgundy where he showed off his rare books and art. “Traveling with Tyler,” noted London OSS chief David Bruce, “is like taking a witty, urbane, human Baedeker as a courier.” The contessa, who was equally sophisticated, moved in artistic and literary circles. She was at the bedside of Edith Wharton in 1937 when the novelist expired at her villa outside Paris.

Tyler was another one of those refined men who glided smoothly across borders and did not think twice about doing business with Nazi luminaries. During the war, he moved to Geneva to dabble in banking for the Bank for International Settlements. Tyler’s virulent anti-Semitism made him a congenial colleague when the Reich had business to conduct in Switzerland. Well connected in the enemy camp, Tyler was among the first people whom Dulles sought out after arriving in Switzerland.

Now Dulles and Hohenlohe, and their mutual friend Royall Tyler, were gathered amiably around the OSS man’s fireplace at 23 Herrengasse. Dulles broke the ice (#litres_trial_promo) by recalling old times with Prince Max in Vienna and New York. Then the men quickly got down to business—trying to determine whether a realpolitik deal could be struck between Germany and the United States that would take Hitler out of the equation but leave the Reich largely intact. As they spun out their visions for a postwar Europe, there was much common ground. Dulles and Hohenlohe clearly saw the Soviet Union as the enemy, with a strong Germany as a bastion against the Bolshevik and Slavic menace. The two old friends also agreed that there was probably no room for the Jewish people in postwar Europe, and certainly they should not return to positions of power. Dulles offered that there were some in America who felt the Jews should be resettled in Africa—an old dream of Hitler’s: the Führer had once fantasized about sending the pariah population to Madagascar.

The two men were too worldly to engage in any emotional discussion about the Holocaust. Dulles put the prince at ease by telling him that he “was fed up with hearing from all the outdated politicians, emigrants and prejudiced Jews.” He firmly believed that “a peace had to be made in Europe in which all of the parties would be interested—we cannot allow it to be a peace based on a policy of winners and losers.”

Instead of Roosevelt’s “unconditional surrender,” in which the Nazi leadership would be held accountable for their crimes against humanity, Dulles was proposing a kind of no-fault surrender. It was a stunningly cynical and insubordinate gambit. The pact that Dulles envisioned not only dismissed the genocide against the Jews as an irrelevant issue, it also rejected the president’s firmly stated policy against secret deal making with the enemy. The man in the White House, clinging to his anti-Nazi principles, was clearly one of those “outdated politicians” in Dulles’s mind. While boldly undermining his president, Dulles had the nerve to assure Hohenlohe that he had FDR’s “complete support.”

The fireplace meeting was, in fact, a double betrayal—Dulles’s of President Roosevelt, and the Nazi prince’s of Adolf Hitler. Hovering over the tête-à-tête (#litres_trial_promo) at 23 Herrengasse was the presence of Heinrich Himmler. He was the Reich’s second most powerful man, and he dared to think he could become number one. With his weak chin, caterpillar mustache, and beady eyes gazing out from behind wire-rim glasses, Himmler looked less an icon of the master race than an officious bank clerk. The former chicken farmer and fertilizer salesman inflated himself by claiming noble heritage and was given to explorations of the occult and other flights of fantasy. But Himmler was a steely opportunist and he ruthlessly outmaneuvered his rivals, rising to become Hitler’s indispensable deputy and the top security chief for the Nazi empire.

It was Himmler whom the Führer had entrusted with the Final Solution, their breathtaking plan to wipe the Jewish people from the face of the earth. It was Himmler who had the nerve to justify this plan, standing before his SS generals in October 1943 and assuring them that they had “the moral right to destroy this people which wanted to destroy us,” to pile up their “corpses side by side” in monuments to the Reich’s power. As Hannah Arendt later observed, Himmler was the Nazi leader most gifted at solving the “problems of conscience” that sometimes nagged the Reich’s executioners. With his “winged words,” as his diligent administrator of death, Adolf Eichmann, put it, Himmler transformed his men’s gruesome work into a grand and secret mission that only the SS elite were capable of fulfilling. “The order to solve the Jewish question, this was the most frightening an organization could ever receive,” Himmler told the leaders of his killing teams. He knew how to appeal to his men’s sense of valor and vanity, telling them, “To have stuck it out and, apart from exceptions caused by human weakness, to have remained decent, that is what has made us hard. This is a page of glory in our history which has never been written and is never to be written.”

And, in the end, it was Himmler who—despite his long enchantment with the Hitler cult—had the brass to consider replacing his Führer when he realized that the war could not be won militarily. Prince Max was only one of the emissaries Himmler dispatched across Europe to seek a separate peace deal with the United States and England. At one point, Himmler even recruited fashion designer Coco Chanel (#litres_trial_promo), bringing her to Berlin to discuss strategy.

Himmler knew he was playing a very dangerous game, letting Hitler know just enough about his various peace feelers, but not enough to arouse suspicion. Dulles, too, understood that he was playing with fire by defying presidential orders. After receiving a warning from Washington about the perils of fraternizing with Hohenlohe, Dulles sent back a cagey reply, cabling that he realized the prince was a “tough customer and extreme caution required,” but he might prove “useful.” Dulles did not find it necessary to inform his superiors just how deeply involved he was with Himmler’s envoy.

Dulles and Tyler met with Hohenlohe on several other occasions over the next few weeks, from February into April. And even as late as November 1943, Dulles continued to forward to Washington Prince Max’s reports on Himmler’s frame of mind. Dulles regarded the prince as a serious enough collaborator to give him a secret OSS code number, 515.

In the end, Dulles’s machinations with Hohenlohe went nowhere. President Roosevelt was very much in control of the U.S. government, and his uncompromising position on Nazi capitulation was still firmly in place. When OSS chief Wild Bill Donovan informed the president about the Himmler peace initiatives, FDR made it clear that he remained adamantly opposed to cutting any deals with the Nazi high command. As long as that was presidential policy, there was nothing Dulles could do but bide his time and maintain his secret lines to the enemy.

Despite Heinrich Himmler’s elusive quest to cut a deal with the Allies, he never lost faith in Dulles (#litres_trial_promo). On May 10, 1945, just days after the war ended, Himmler set out from northern Germany with an entourage of SS faithful, heading south toward Switzerland—and the protection of the American agent. He was disguised in a threadbare blue raincoat and wore a patch over one eye, with his trademark wire-rims stashed in his pocket. But Himmler never made it to his rendezvous with Dulles. The SS chief and his retinue were captured by British soldiers as they prepared to cross the Oste River. While in custody, Himmler cheated the hangman by biting down on a glass capsule of cyanide.

Even if Himmler had made it to Switzerland, however, he would not have found sanctuary. He was too prominent a face of Nazi horror for even Dulles to salvage. But the American spy would come to the rescue of many other Nazi outlaws from justice.

2 (#ucb0e78d6-37f6-5f62-8467-92bd478b818a)

Human Smoke (#ucb0e78d6-37f6-5f62-8467-92bd478b818a)

Neither Allen, Foster, nor their three sisters were ever as devout as their father, the Reverend Allen Macy Dulles, who presided over a small Presbyterian flock in Watertown, New York, a sleepy retreat favored by New York millionaires near Lake Ontario. But the siblings always regarded the family’s summer vacations on nearby Henderson Harbor as some kind of heaven. The huge lake and its sprinkling of islands held countless adventures for the children. The boys would rise early (#litres_trial_promo) in the morning and, in the company of a lean, laconic fishing guide, set off in a skiff, stalking the waters for the lake’s delicious smallmouth black bass. At noon, they would ground their little sailboat on one of the islands and cook their catch over a driftwood fire. The fish was fried in crackling pork fat, served with corn and potatoes, and washed down with black coffee. Years later, they would recall these summer feasts as among the best meals of their lives.

Reverend Dulles was not a man of means, and he had difficulty supporting his family on his modest churchman’s salary. His illustrious father-in-law, the luxuriantly bewhiskered John Watson Foster, who had served briefly as secretary of state under President Benjamin Harrison and then established himself as one of Washington’s first power attorneys, was a beneficent presence in the family’s life. Reverend Dulles sometimes resented his dependence on the old man’s generosity. But the whole family thrived during their summer idylls on Lake Ontario, cozily squeezed into a big, red, clapboard cottage that had been built by Grandfather Foster. Their lakeside life was rustic—the house had no electricity and they had to pump their water. But it all seemed enchanted to the children.

There were picnics and moonlight sails, and on the Fourth of July the children would put small candles in paper balloons (#litres_trial_promo) and set them floating in the air, watching as the golden lanterns drifted over the glittering water toward Canada. In the early evenings, Eleanor—the next oldest sibling after Allen—liked to sit on the family’s dock and watch the clouds gather over the lake, casting red and pink shafts on the darkening water. “I never feared hell (#litres_trial_promo) and I thought heaven would be like Henderson but more so,” she mused in her later years.

Eleanor was exceedingly bright and curious, and she refused to resign herself to the prim, petticoat world to which girls of her generation were supposed to confine themselves. When the boys and men would go fishing, she would sometimes plunk herself down in the middle of the boat. When robed Chinese dignitaries and other exotic figures from her grandfather’s diplomatic forays would pay visits to Henderson Harbor, she would be certain to listen in on their conversations. Eleanor’s intelligence and determination would take her far, as she followed her brothers into the diplomatic corps, where she would eventually take over the State Department’s German desk during the critical years after World War II. But, as a brainy woman in a thoroughly male arena, she was always something of an outsider. Even her brothers were often perplexed about how to handle her. With her dark, wiry hair and thick eyeglasses, she considered herself the ugly duckling in the family. Her slightly askew status in the Dulles constellation seemed to heighten her powers of observation, however. Eleanor often had the keenest eye when it came to sizing up her family, especially her two brothers.

Allen loomed large in her life. She attached herself to him at an early age, but she learned to be wary of his sudden, explosive mood shifts. Most people saw only Allen’s charm and conviviality, but Eleanor was sometimes the target of his inexplicable eruptions of fury. Her infractions were often minor. Once Allen flew into a rage over how closely she parked the car to the family house. His moods were like the dark clouds that billowed without warning over Lake Ontario. Later in life, Eleanor simply took herself? “out of his orbit to avoid the stress and furor that he stirred in me.”

Allen was darker and more complex than his older brother, and his behavior sometimes mystified his sister. One summer incident (#litres_trial_promo) during their childhood would stick with Eleanor for the rest of her life. Allen, who was nearly ten at the time, and Eleanor, who was two years younger, had been given the task of minding their five-year-old sister Nataline. With her blond curls and sweet demeanor, Nataline—the baby in the family—was usually the object of everyone’s attention. But that day, the older children got distracted as they skipped stones across the lake’s surface from the family’s wooden dock. Suddenly, Nataline, who had retrieved a large rock to join in the game, went tumbling into the water, pulled down by the dead weight of her burden. As the child began floating away toward the lake’s deep, cold waters, her pink dress buoying her like an air balloon, Eleanor began screaming frantically. But Allen, who by then was a strong swimmer, was strangely impassive. The boy just stood on the dock and watched as his little sister drifted away. Finally, as if prompted by Eleanor’s cries, he, too, began yelling. Drawn by the uproar, their mother—who was recovering in bed from one of her periodic, pounding migraines—came flying down the dock and, plunging into the water, rescued little Nataline.

Throughout his life, Allen Dulles was slow to feel the distress of others. As a father, his daughter Joan would recall, Dulles seemed to regard his children with a curious remoteness, as if they were visitors in his house. Even his son and namesake Allen Jr. made little impact on him when he excelled in prep school and at Oxford, or later, in the Korean War, when the young man was struck in the head by a mortar shell fragment and suffered brain damage. Clover Dulles called her cold and driven husband “The Shark.”

Allen did not take after his father. Reverend Dulles, a product of Princeton University and Germany’s Göttingen University, was a scholarly, meditative type. While his children explored the wilds of Lake Ontario, he was likely to be sequestered in his upstairs study with his Sunday sermon. The minister was a compassionate man (#litres_trial_promo). While walking home one frigid day, he took off his coat and gave it to a man shivering in the street. On another occasion, he risked expulsion from the Presbyterian Church for performing a marriage for a divorced woman.

It was her mother, Eleanor would recall, who ran the family. Edith Foster Dulles was (#litres_trial_promo) “a doer (#litres_trial_promo),” the kind of woman who “believed in action.” Eleanor would remember her cracking the whip on her father. “Now, Allen,” she would tell her husband, “you’ve been working on that book for five or six years. Don’t you think it’s good enough? Let’s publish it.”

The reflective pastor was less of an influence on his sons than their mother and grandfather. The Dulles boys were drawn to the men of action who called on Grandfather Foster, men who talked about war and high-stakes diplomacy, men who got things done. Foster and Allen both lacked their father’s sensitive temperament. Like Allen, Foster felt little empathy for those who were weak or vulnerable. He understood that there was misfortune in the world, but he expected people to put their own houses in order.

Foster’s callousness came into stark (#litres_trial_promo) relief during the Nazi crisis in Germany. In 1932, as Hitler began his takeover of the German government, Foster visited three Jewish friends, all prominent bankers, in their Berlin office. The men were in a state of extreme anxiety during the meeting. At one point, the bankers—too afraid to speak—made motions to indicate a truck parked outside and suggested that it was monitoring their conversation. “They indicated to him that they felt absolutely no freedom,” Eleanor recalled.

Foster’s reaction to his friends’ terrible dilemma unnerved his sister. “There’s nothing that a person like me can do in dealing with these men, except probably to keep away from them,” he later told Eleanor. “They’re safer, if I keep away from them.” Actually, there was much that a Wall Street power broker like John Foster Dulles could have done for his endangered friends, starting with pulling strings to get their families and at least some of their assets out of Germany before it was too late.

Throughout her life, Eleanor wrestled with her brothers’ cold, if not cruel, behavior. A family loyalist to the end, she generally tried to give her brothers the most charitable interpretation possible. But sometimes the brothers strained even her sisterly charity. The same year that Foster sidestepped the urgent concerns of his Jewish friends in Berlin, Eleanor informed him that she intended to marry David Blondheim, the man she had been in love with ever since meeting him in Paris in 1925. Blondheim was a balding, middle-aged linguistics professor at Johns Hopkins University—with “a very sensitive mouth (#litres_trial_promo),” in Eleanor’s estimation, “and clear, brown eyes.” He was also a Jew. Eleanor’s parents had given Blondheim their approval, calling him “charming,” after meeting him and Eleanor for dinner during a visit to Paris. But by 1932, Reverend Dulles was dead and Foster was head of the family. And he had a different perspective on the mixed marriage that his sister and her fiancé finally felt brave enough to attempt.

Foster wrote Eleanor a letter, asking her if she realized “the complications of marrying a Jew”—and helpfully pointing out a dozen such problems. Her brother’s letter stunned and infuriated (#litres_trial_promo) Eleanor, who by then was in her midthirties and not in need of her brother’s counsel in such matters. She promptly replied, but, not wanting to directly defy her imposing brother, she sent the letter to his wife, Janet. In her letter, Eleanor made it clear that Foster need not trouble himself with her life’s “complications” and that, in the future, she would simply “go my own way.”

Years later, Eleanor tried to explain away her brother’s behavior. He was not motivated by anti-Semitism, she insisted. He was just a product of his social and professional milieu. In his circles, she explained, people would say, “We can’t have too many Jews (#litres_trial_promo) in this club” or “We can’t have too many Jews in this firm.” Foster simply saw this attitude as a fact of life, Eleanor observed—“just like the climate.”

In 1934, the fragile Blondheim (#litres_trial_promo), distressed by the growing cataclysm in Europe and private demons, sunk into depression and killed himself, sticking his head into the kitchen oven. Reasserting himself as paterfamilias, Foster swept back into the deeply shaken life of his sister and took charge. The suicide must, of course, be hushed up. And Eleanor must instantly shed the dead man’s name, or she would be haunted by it in years to come. Eleanor dutifully complied with Foster’s direction and the name Blondheim was purged from the Dulles family record, as if the brilliant man with the sensitive mouth and clear, brown eyes had never existed. The fact she was about to give birth to Blondheim’s son was a bond that Foster could never make disappear.