По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

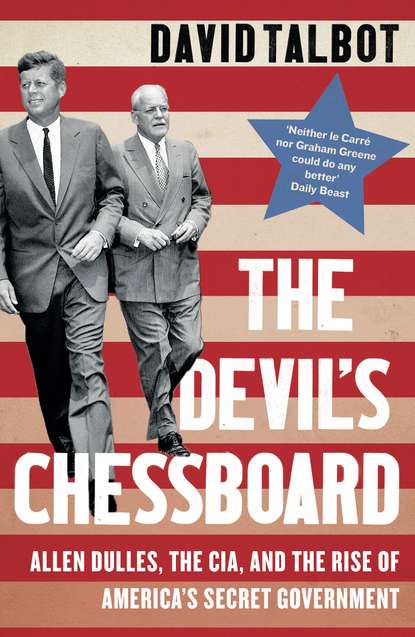

The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Goering’s evasion of the gallows proved wise. The following morning, the ten remaining men who had been sentenced to death filed one by one into a gymnasium adjacent to the courtroom, where three black-painted wooden scaffolds awaited them. With its cracked plaster walls and glaring lighting, the gymnasium—which had hosted a basketball game just days before between U.S. Army security guards—provided a suitably bleak backdrop. The chief hangman, a squat, hard-drinking Army master sergeant from San Antonio named John C. Woods, was an experienced executioner, with numerous hangings to his credit. But, due to sloppiness or ill will, the Nuremberg hangings were not professionally carried out.

The drop was not long enough (#litres_trial_promo), so some of the condemned dangled in agony at the end of their ropes for long stretches of time before they died. Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel, Hitler’s war minister and the second-highest-ranking soldier after Goering to be tried at Nuremberg, suffered the longest, thrashing for a full twenty-four minutes. When the dead men were later photographed, they looked particularly ghoulish, since the swinging trapdoors had smashed and bloodied their faces as the men fell—another flaw, or intentional indignity, in the execution process.

Julius Streicher, defiant to the end, screamed a piercing “Heil Hitler!” as he began climbing the thirteen wooden steps of the scaffold. As the noose was placed around his neck, he spat at Woods, “The Bolsheviks will hang you one day.” The short drop failed to kill him, too, and as Streicher groaned at the end of his rope, Woods was forced to descend from the platform, grab his swinging body, and yank sharply downward to finally silence him.

After the first executions, the American colonel in charge asked for a cigarette break. The soldiers on the execution team paced nervously around the gymnasium, smoking and speaking somberly among themselves. But after it was all over, Woods pronounced himself perfectly satisfied. “Never saw a hanging go off any better,” he declared.

The hangman never expressed any doubt about his historic role at Nuremberg. “I hanged those ten Nazis … and I am proud of it,” he said after the executions. A few years later, Woods accidentally electrocuted himself while repairing faulty machinery at a military base in the Marshall Islands.

The sectors of Germany occupied by the United States and its allies tried to quickly forget the war. Hollywood musicals and cowboy adventures—and their escapist German equivalents—flooded the movie theaters in West Germany. But in the Soviet-controlled East, there was a cinematic effort, though generally party-directed and heavy-handed, to force the German people to confront the nightmare and its consequences. In the early postwar period, there was a barrage of such dark movies, known as Trümmerfilme, or “rubble films.” One of the more artful rubble films (#litres_trial_promo), Murderers Among Us, grappled disturbingly with the Nazi ghosts that still haunted Germany. Produced in 1946 by DEFA, the Soviet-run studio in East Berlin, Murderers Among Us was directed by Wolfgang Staudte, a once-promising young filmmaker who had made his own moral compromises in order to continue working during Hitler’s rule. Staudte’s film reverberates with guilt.

In the film, Dr. Hans Mertens, a German surgeon who had served with the Wehrmacht, returns to Berlin after the war. The city is a monument to rubble; it seems to have been deconstructed stone by stone, brick by brick. Staudte needed no studio back lot or special effects. Demolished Berlin was his sound stage. Dr. Mertens, who wants to forget everything he has witnessed during the war, wanders drunk and obliterated through the city’s ruins. But his past won’t release him. He comes across his former commander, Captain Bruckner, a happily shallow man who, despite the atrocities he ordered during the war, has returned to a prosperous life in Berlin as a factory owner.

“Don’t look so sad,” Bruckner tells the doctor as the two men pick their way through the rubble one day in search of a hidden cabaret. “Every era offers its chances if you find them. Helmets from saucepans or saucepans from helmets. It’s the same game. You must manage—that’s all.”

Dr. Mertens’s bitterness deepens as he observes Berlin being profitably revived by the very men who destroyed it. One day, fortified by drink, he comes across a lively nest of vermin, scurrying about in the rubble. “Rats,” he says to himself. “Rats everywhere. The city is alive again.”

By the end of the film, Mertens has emerged from his drunken anesthesia and has begun to consider a path of action. How do you make a better world after a reign of terror like Hitler’s? Should he kill a man like Bruckner? Should he try to bring him to justice?

Murderers Among Us ends on a hopeful, if fanciful, note. Mertens imagines Bruckner behind bars—no longer looking smug, but stricken. “Why are you doing this to me?” he screams, as images of his victims float ghostlike around him.

When the movie was produced, the first Nuremberg trial was still under way, and it looked to the world as if justice would indeed prevail. But as the years went by, a surprising number of men like Bruckner not only escaped justice but thrived in the new Germany. Thanks to officials like Dulles, many Bruckners shimmied free from their cages. The rats were everywhere.

4 (#ulink_6d4ec59e-8ea4-54cc-9b54-bd9c3b4e6d79)

Sunrise (#ulink_6d4ec59e-8ea4-54cc-9b54-bd9c3b4e6d79)

Allen Dulles’s most audacious intervention on behalf of a major Nazi war criminal took place in the waning days of the war. The story of the relationship between Dulles and SS general Karl Wolff—Himmler’s former chief of staff and commander of Nazi security forces in Italy—is a long and tangled one. But perhaps it’s best to begin at a particularly dire moment for Wolff, in the still-dark early morning hours of April 26, 1945, less than two weeks before the end of the war in Europe.

That morning, soon after arriving at the SS command post in Cernobbio, a quaint town nestled in the foothills of the Italian Alps on the shores of Lake Como, Wolff was surrounded by a well-armed unit of Italian partisans. The partisans had established positions around the entire SS compound, a luxurious estate that had been seized by the Nazis from the Locatelli family, a wealthy dynasty of cheese manufacturers. With only a handful of SS soldiers standing guard outside his villa, Wolff had no way to break through the siege and his capture seemed imminent. As chief of all SS and Gestapo units in Italy, Wolff was well known to the Italian resistance, who blamed him for the reprisal killings of many civilians in response to partisan attacks on Nazi targets, as well as for the torture and murder of numerous resistance fighters. If he fell into the partisans’ hands, the SS commander was not likely to be treated charitably.

At age forty-four, the tall, fair-haired, blue-eyed Wolff carried himself with the supreme self-confidence of a man who had long been paraded around by the Nazi high command as an ideal Aryan specimen. A former advertising executive, Wolff understood the power of imagery. His climb through the Nazi Party ranks had been paved by his Hessian bearing, his imperial, hawk-nosed profile, and the erect figure he cut in his SS dress uniform. Himmler, the former chicken farmer, drew confidence from Wolff’s suave presence and fondly called him “Wolffie.” The SS chief made Wolff his principal liaison to Hitler’s headquarters, where he also quickly became a favorite.

Hitler enjoyed showing off Wolff at his dinner parties and made sure that the SS-Obergruppenführer was by his side during the war’s tense overture, when German forces invaded Poland and Hitler prepared to join his troops at the front. “To my great and (#litres_trial_promo), I openly admit, joyful surprise, I was ordered to the innermost Führer headquarters,” Wolff proudly recalled as an old man. “Hitler wanted to have me nearby, because he knew that he could rely on me completely. He had known me for a long time, and rather well.”

But in April 1945, encircled by his enemies at the Villa Locatelli, Wolff was far from these glory days. The desperation of his situation was underlined the following day when Benito Mussolini, Italy’s once all-powerful Duce, whose status had been reduced to that of Wolff’s ward, was captured by partisans at a roadblock on the northern tip of Lake Como while fleeing with his dwindling entourage for Switzerland. Taken to the crumbling but still grand city hall in the nearby lakeside village of Dongo, Mussolini was assured he would be treated mercifully. “Don’t worry (#litres_trial_promo),” the mayor told him, “you will be all right.”

A horde of partisans and curious townspeople crowded into the mayor’s office, to fire questions at the man who had ruled Italy for over two decades. Mussolini answered each question thoughtfully. In the final months of his life, he had grown increasingly reflective and resigned to his fate. He spent more time reading—his tastes ranged from Dostoyevsky and Hemingway to Plato and Nietzsche—than dealing with governmental affairs. “I am crucified (#litres_trial_promo) by my destiny,” Mussolini had told a visiting Italian army chaplain in his final days.

When his captors asked him why he had allowed the Germans to exact harsh retributions on the Italian people, Mussolini mournfully explained that it was beyond his power. “My hands were tied (#litres_trial_promo). There was very little possibility of opposing General [Albert] Kesselring [field commander of the German armed forces in Italy] and General Wolff in what they did. Again and again in conversations with General Wolff, I mentioned that stories of people being tortured and other brutal deeds had come to my ears. One day Wolff replied that it was the only means of extracting the truth, and even the dead spoke the truth in his torture chambers.”

In the end, Mussolini found no mercy. He and his mistress, Claretta Petacci, who insisted on sharing his fate, were machine-gunned and their bodies were put on display in Milan’s Piazzale Loreto. Mussolini’s body was subjected to particular abuse by the large, frantic crowd in the square; one woman fired five shots into Il Duce’s head—one for each of her five dead sons. The bodies were then strung up by their feet from the overhanging girders of a garage roof, where they were subjected to further indignities. When he heard about Mussolini’s grotesque finale, Hitler—who, near the end, had told the Duce that he was “perhaps the only friend I have in the world”—ordered that his own body be burned after he killed himself.

General Wolff knew that he, too, faced a merciless end if he fell captive at Villa Locatelli. But unlike Mussolini, the SS commander had a very dedicated and powerful friend in the enemy camp.

At eleven in the morning on April 26, Allen Dulles received an urgent phone call in his Bern office from Max Waibel, his contact in Swiss intelligence. Waibel reported that Karl Wolff was surrounded by partisans at Villa Locatelli and “there was a great danger (#litres_trial_promo) they might storm the villa and kill Wolff.”

The SS general was the key to Dulles’s greatest wartime ambition: securing a separate peace with Nazi forces in Italy before the Soviet army could push into Austria and southward toward Trieste. With the Communists playing a dominant role in the Italian resistance, Dulles knew that blocking the advance of the Red Army into northern Italy was critical if Italy was to be prevented from falling into the Soviet orbit after the war. Dulles and his intelligence colleagues had been secretly meeting with Wolff and his SS aides since late February, trying to work out a separate surrender of German forces in Italy that would save the Nazi officers’ necks and win the OSS spymaster the glory that had eluded him throughout the war.

The negotiations for Operation Sunrise, as Dulles optimistically christened his covert peace project, were a highly delicate dance. Exposure could spell disaster for both men. According to Wolff, during their diplomatic courtship, Dulles identified himself as a “special representative (#litres_trial_promo)” and “a personal friend” of President Roosevelt—neither of which was true. In fact, by negotiating with the SS general, Dulles was clearly violating FDR’s emphatic policy of unconditional surrender. Just days before Wolff was trapped at Villa Locatelli, Dulles had been expressly forbidden by Washington from continuing his contacts with Wolff.

Meanwhile, the SS commander’s secret diplomatic efforts both dovetailed and competed with the numerous other Nazi peace initiatives coming Dulles’s way, including that of his boss, Heinrich Himmler, who was also shrewd enough to realize that the German war effort was doomed and he along with it, unless he managed to cut his own deal. Even the Führer himself was toying with the idea of how he might save the Reich by splitting the Allies and winning a favorable peace settlement. In his backroom dealing with Dulles, Wolff at times found himself an emissary of the Nazi high command and at other times a traitorous agent working at cross-purposes to save his own skin.

But with Wolff now surrounded by Italian resistance fighters at Villa Locatelli, his end seemed near—and with it, all the painstaking and duplicitous efforts undertaken by the two men over the previous two months on behalf of Operation Sunrise. Dulles had too much at stake to let his happen. Alerted to Wolff’s predicament, he flew into action, mounting a rescue party to cross the border and reach the villa before it was too late.

Dulles knew that risking brave men to save a Nazi war criminal’s life—in the interests of his own unsanctioned peace mission—was an act of brazen insubordination that could cost him his intelligence career. So, to give himself cover, Dulles arranged for his loyal subordinate, Gero von Schulze-Gaevernitz, to oversee the rescue.

Dulles later related the story with typical bonhomie—but, as was often the case, his glib delivery masked a darker tale. “I told Gaevernitz that under the strict orders (#litres_trial_promo) I had received, I could not get in touch with Wolff … Gaevernitz listened silently for a moment. Then he said that since the whole [Operation Sunrise] affair seemed to have come to an end, he would like to go on a little trip for a few days. I noticed a twinkle in his eye, and as he told me later, he noticed one in mine. I realized, of course, what he was going to do, and that he intended to do it on his own responsibility.”

When it came to saving Wolff, Gaevernitz shared his boss’s zeal. Gaevernitz was the handsome scion of an illustrious European family and a relative of the Stinnes family, whose fortune had helped finance Hitler’s political rise. The Gaevernitzes had broken from the Nazis early on, and Dulles helped funnel their money to safe havens outside of Germany, as he did for many wealthy Germans, including those who remained loyal to the Nazi regime, before and during the war. Dulles and Gaevernitz were also tied together by their political views—they both believed that “moderate” members of Hitler’s regime must be salvaged from the war’s wreckage and incorporated into postwar plans for Germany. By the extremely generous standards of Dulles and Gaevernitz, even Karl Wolff qualified as one such redeemable Nazi.

After being dispatched by Dulles, Gaevernitz, accompanied by the Swiss secret agent Waibel, jumped on an Italy-bound train, arriving at the Swiss border town of Chiasso late that evening. There they met one of Dulles’s top agents, Don Jones, a man well known to the Italian resistance fighters in the border area as “Scotti.” Gaevernitz thought that Scotti, a man who risked his life each day fighting SS soldiers, would balk at the idea of saving the general who commanded them. But Scotti gamely agreed to lead the mission.

And so, as midnight approached, a convoy of three cars set off toward the western shore of Lake Como. One vehicle carried OSS agent Scotti and three Swiss intelligence operatives, the second was filled with Italian partisans, and the third conveyed two SS officials Dulles had recruited to ease the convoy’s passage through German-controlled areas. It was one of the most bizarre missions in wartime Europe: a joint U.S.-German rescue effort organized for the benefit of a high-ranking Nazi general.

As the convoy crawled through the dark toward the lake, partisans opened fire on the cars. Scotti bravely jumped out of his vehicle and stood in the headlights, praying that the resistance soldiers would recognize him and stop shooting. Fortunately, one did. There was more gunfire and even a grenade attack as they continued their journey, but finally, the odd rescue team arrived at the Villa Locatelli. After talking their way past the partisans’ blockade as well as the SS guard, they entered the villa and found General Wolff in full SS uniform, as if he had been expecting them all along. He offered the rescue party some of the vintage Scotch he kept for special occasions, volunteering that the whiskey had been expropriated from the British by Rommel during the North African campaign.

It was after two in the morning when the caravan arrived safely back in Chiasso with their special passenger, who had changed into civilian clothes for the journey and was slumped low in the backseat of the middle car. Gaevernitz was anxiously awaiting the rescue team’s return in the dingy railroad station café. He had no intention of greeting Wolff in public. But when the SS general heard that Dulles’s aide was there, he bounded over to him and shook his hand. “I will never forget what you have done (#litres_trial_promo) for me,” Wolff declared.

Dulles and Gaevernitz would learn that the SS man had a strange sense of gratitude. In the coming years, Wolff would become a millstone around their necks.

Later that morning, an exhausted Gaevernitz, who had not been out of his clothes all that night, took a train to his family’s lovely villa in Ascona, on Lake Maggiore, so he could enjoy a long sleep. At the railway station in Locarno, where he stopped for breakfast, he listened to the 7:00 a.m. radio broadcast, which was filled with news of Mussolini’s capture and other dramatic bulletins from the Lake Como area. Gaevernitz kept expecting to hear news of General Wolff’s rescue by a U.S.-led team of commandos; he was determined that his boss’s name must be kept out of the story.

“It would have made a lovely headline (#litres_trial_promo) in the papers,” Gaevernitz later mused in his diary. “‘German S.S. General Rescued From Italian Patriots by American Consul’!!! Poor Allen!! I really felt I had to spare him this [embarrassment].”

It took Wolff several more days of high-stakes diplomacy before his maneuvers finally resulted in the surrender of German forces on the Italian front on May 2, 1945. By then, Hitler was dead, the German military machine had all but collapsed, and it was just six days before the capitulation of all Axis forces in Europe. In the end, Operation Sunrise saved few lives and had little impact on the course of the war. It did succeed, however, in creating a new set of international tensions that some historians would identify (#litres_trial_promo) as the first icy fissures of the Cold War.

The Dulles-Wolff maneuvers aggravated Stalin’s paranoid disposition. While he was still alive, Roosevelt, whom Stalin genuinely liked and trusted, was able to reassure the Soviet leader that the United States had no intention of betraying an alliance forged in blood. But after FDR’s death, Stalin’s fears of a stab in the back at Caserta—where the surrender on the Italian front was signed by German and American military commanders—only grew more intense. His suspicions were not unfounded. After the separate peace was declared at Caserta, some German divisions (#litres_trial_promo) in Italy were told not to lay down their arms but to get ready to begin battling the Red Army alongside the Americans and British.

Even Roosevelt’s successor, Harry S. Truman, who would become a dedicated Cold Warrior, took a dim view of Operation Sunrise and tried unsuccessfully to shut it down. Truman later wrote in his memoir (#litres_trial_promo) that Dulles’s unauthorized diplomacy stirred up a tempest of trouble for him during his first days as president.

Operation Sunrise would become Allen Dulles’s creation myth, the legend that loomed over his entire intelligence career. For the rest of his life, the spymaster would energetically work the publicity machinery on “the secret surrender,” generating magazine articles and more than one book and attempting to turn the tale into a Hollywood thriller. It was, according to the story that Dulles assiduously spun throughout the rest of his life, a feat of daring personal diplomacy. Time magazine—which, under the ownership of his close friend Henry Luce, could always be counted on to give Dulles good press—trumpeted Operation Sunrise as “one of the most stunning triumphs (#litres_trial_promo) in the history of secret wartime diplomacy.” The reality, however, was far from triumphant.

Karl Wolff was Allen Dulles’s kind of Nazi. Like Hitler and Himmler, Dulles admired Wolff’s gentlemanly comportment and found him “extremely good-looking.” He struck Dulles as a man with the right sort of pedigree, the type of trustworthy fellow with whom he could do business.

Wolff liked to present himself as a high-level administrator who was unsullied by the more inhumane operations of his government. He was not one of the Nazi Party’s vulgar anti-Semites, he would later insist. He took pride in rescuing the occasional prominent Jewish prisoner from the Gestapo dungeons—a banker, a tennis celebrity, for instance. Eichmann sneeringly referred to Wolff as one of the “dandy officers of the SS (#litres_trial_promo), who wore white gloves and didn’t want to know anything about what’s going on.”

Wolff was a financially savvy fixer, a man whom the Nazi hierarchy could rely on to get things done. After serving with distinction as a young army officer on the western front during World War I, Wolff originally pursued a career in banking, before going into advertising. But his ambitions in both fields were thwarted by Germany’s postwar economic crash. His decision to join Hitler’s rapidly growing enterprise, where he rose quickly through the ranks, was more of a professional decision than an ideological one. There were unlimited opportunities in the Nazi movement for a polished blond warrior like Wolff.

His business background gave Wolff cachet in the SS, where such skills were in short supply. It was Wolff who was put in charge of Himmler’s important “circle of friends,” a select group of some three dozen German industrialists and bankers who supplied the SS with a stream of slush money. “Himmler was no businessman (#litres_trial_promo) and I took care of banking matters for him,” Wolff later recalled. In return for their generosity, the corporate donors were given special access to pools of slave labor. They were also invited to attend high-level government meetings and special Nazi Party ceremonies. It was said that Wolff took such good care of the wealthy contributors at the 1933 Nuremberg rally that they were pampered more than the Führer himself. On other occasions, the privileged circle of friends was even taken on private tours of the Dachau and Sachsenhausen concentration camps, escorted by Himmler and Wolff. Presumably the SS shut down the camps’ crematoria during the distinguished guests’ visits to spare them the unpleasant stench.

In pursuing the Sunrise peace pact, Dulles and Wolff harbored similar political motives. Both viewed the Soviet army’s advance into Western Europe as a catastrophe. But they also shared business interests. Throughout the war, Dulles had used his OSS command post in Switzerland to look out for Sullivan and Cromwell business clients in Europe. Stopping the war before these clients’ manufacturing and power plants in industrial northern Italy were destroyed was a priority for both men.

Under the terms of Operation Sunrise, Wolff specifically agreed not to blow up the region’s many hydroelectric plants, which generated power from the water roaring down from the Alps. Most of these installations were owned by a multinational holding company called Italian Superpower Corporation (#litres_trial_promo). Incorporated in Delaware in 1928, Italian Superpower’s board was evenly divided between American and Italian utility executives, and by the following year the power company was swallowed by a bigger, J. P. Morgan–financed cartel. The ties between Italian Superpower and Dulles’s financial circle were reinforced when, toward the end of the war, the spymaster’s good friend—New York banker James Russell Forgan—took over as his OSS boss in London. Forgan was one of Italian Superpower’s directors.

Dulles concluded that Wolff was, in effect, a member of his international club—a man with similar views, connections, and willingness to do business. Neither man was particularly interested in the clash of ideas or human tragedies associated with the war. They were fixed on the calculus of power; each understood the other’s intense ambition. Operation Sunrise was for both of them a bold, high-wire career move.

After he decided that Wolff was a dependable partner, Dulles went to great lengths to rehabilitate the SS commander’s image. In his reports back to OSS headquarters, he framed Wolff in the best possible light: he was a “moderate” (#litres_trial_promo) and “probably the most dynamic [German] personality in North Italy.” Although some U.S. and British intelligence officials suspected that Wolff was serving as an agent of Hitler and Himmler and trying to drive a wedge between the Allies, Dulles insisted that the German general was acting heroically and selflessly to bring peace to Italy and to spare its land, people, and art treasures from a final, scorched-earth conflagration.