По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

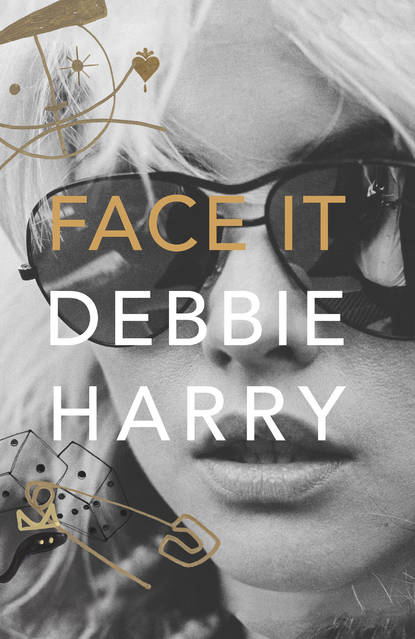

Face It: A Memoir

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

My dad went there to work, but I went there for fun. Once a year, my maternal grandmother would take me to the city to buy me a winter coat at Best & Co., a famous, conservative, old-style department store. Afterward we’d go to Schrafft’s on Fifty-Third Street and Fifth Avenue. This old-fashioned restaurant was almost like a British tearoom, where well-dressed old ladies sat primly sipping from china cups. Very proper—and a refuge from the city bustle.

At Christmastime my family would go to see the tree in Rockefeller Center. We’d watch the skaters at the skating rink and look at the department store windows. We weren’t sophisticated city-goers, coming to see a show on Broadway; we were suburbanites. If we did go to a show it would be at Radio City Music Hall, although we did go to the ballet a couple of times. That’s probably what fostered my dream of being a ballerina—which didn’t last. But what did last was how excited and intrigued I was about performance and the whole thing of being onstage. Though I loved the movies, my reaction to those live shows was physical—very sensual. I had the same reaction to New York City and its smells and sights and sounds.

One of my favorite things as a kid was heading down to Paterson, where both my grandmothers lived. My father liked to take the back roads, winding through all the little streets in the slum areas. And much of Paterson was very old and neglected at that time, pre-gentrification, full of migrant workers who’d come to find jobs in the factories and the silk-weaving mills. Paterson had earned the title “Silk City.” The Great Falls of the Passaic River drove the turbines that drove the looms. Those falls had stared me in the face throughout my childhood, thanks to the Paterson Morning Call. On its masthead at the top of its front page sat a pen-and-ink drawing of the billowing waters.

Dad would always drive real slow down River Street, because it teemed with people and activity. There were gypsies who lived in the storefronts; there were black people who’d come up from the South. They dressed in brilliant clothing and wrapped their hair in do-rags. For a little girl from a white-on-white, middle-to-lower-middle-class burb, this was an eyeful. Wonderful. I would be hanging out the window, crazed with curiosity, and my mother would be snapping, “Get back in the car! You’re going to get your head chopped off!” She’d have rather not driven down River Street, but my dad was one of those people who like to have their secret way. Yay for Dad!

I find it mysterious now, how little was ever revealed, within our family, about my father’s side. Nobody talked about them, what they did, or how they came to be in Paterson. I remember, when I was much older, quizzing my dad about what his grandfather did for a living. He said he was a shoemaker or maybe a shoe repairman from Morristown, New Jersey. I guess he was too low-class for anyone in the family, my father included, to want to be associated with him. Which was kind of tragic, I thought. But my father would remark on how very fortunate his father had been to keep his job all through the Great Depression, selling shoes on Broadway in Paterson. They’d had money coming in when so many, many people were unemployed.

My mother’s family’s Silk City was far more elitist. Her father had had his own seat on the stock exchange before the crash and owned a bank in Ridgewood, New Jersey. So they must have been quite wealthy at some point. When my mother was a child, they would sail to Europe and visit all the capitals on a grand tour, as they used to call it. And she and her siblings all had college educations.

Granny was a Victorian lady, elegant, with aspirations of being a grande dame. My mother was her youngest child. She’d had her rather late in life, which was a cause for arched eyebrows and whispered innuendo within her politely scandalized circle. So when I knew her, she was already quite old. She had long white hair that reached to her waist. Every day Tilly, her Dutch maid, laced her into a pink, full-length corset. I loved Tilly. She had worked for Granny from the time she emigrated to America—first as my mother’s nanny and then as Granny’s cleaner, cook, and gardener. She lived in the house on Carol Street in a beautiful little attic room whose windows opened to the sky. Across the hall, in the storage part of the attic, there were dusty trunks full of curious stuff. I spent many a wonderful hour poking and rummaging through the frayed gowns and yellowed paper and torn photos and dusty books and strange spoons and faded lace and dried flowers and empty perfume bottles and old dolls with china heads. Then finally, breaking into my reverie, a worried call from below. I would close the door softly and slip away. Until next time.

My dad’s first real job after graduating high school was with Wright Aeronautical, the airplane manufacturer, during World War II. His next was with Alkan Silk Woven Labels, who had a mill in Paterson. When I was a little girl and he had to visit the plant, he would take me along with him. I took the tour of the mill many times, but I never once heard what the tour guide said because the looms were so fierce and loud.

The looms really did loom. They were the size of our house, holding thousands and thousands of colored threads in suspension while the shuttles at the bottom zoomed back and forth. At the confluence of all the threads, ribbons would appear and curl out, yard upon yard of silk clothing labels. My father would take these to New York and, like his father before him, play his own small part on the furthest peripheries of the fashion world.

As for me, I loved fashion for as long as I can remember. We didn’t have much money when I was growing up and a lot of my clothes were hand-me-downs. On rainy days when I couldn’t go out I would open up my mother’s wooden blanket chest. The chest was stuffed with clothes she’d picked up from friends or that had been discarded. I would dress up and trot around in shoes and gowns and whatever else I could lay my grubby little hands on.

Television, oh, television. Glowing, ghostly seven-inch screen, round as a fishbowl. Set in a massive box of a thing that would’ve dwarfed a doghouse. Maddening electronic hum. Reception through this bent antenna. Some days good, some days rotten—when the signal flickered and skipped and scratched and rolled.

There wasn’t a whole lot to watch, but I watched it. On Saturday mornings at five A.M. I would be sitting on the floor, eyes glued to the test pattern, black and white and gray, mesmerized, waiting for the cartoons to start. Then came wrestling and I watched that too, thumping the floor and groaning, my anxiety levels soaring at this biblical battle of good vs. evil. My mom would holler and threaten to throw the goddamned thing out if I was going to get that worked up. But wasn’t that the point of it, getting all goddamned worked up?

I was an early and true devotee of the magic box. I even loved watching the picture reduce to a small white dot, then vanish, when you turned the set off.

When baseball season started, Mom would lock me out of the house. My mother, oddly, was a rabid baseball fan, and I mean rabid. She adored the Brooklyn Dodgers. They used to go to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn and watch the games when I was small. So I was always frustrated that I’d be locked outside for a baseball game. But I was a pest, I suppose—with a big mouth to boot.

My mother also liked opera, which she listened to on the radio when it wasn’t baseball season. As far as listening to music, we didn’t have much of a record collection though—a couple of comedy albums and Bing Crosby singing Christmas carols. My favorite was the compilation album I Like Jazz!, with Billie Holiday and Fats Waller and all these different bands. When Judy Garland launched into “Swanee,” I would burst into sobs every time . . .

I had a little radio too, a cute brown Bakelite Emerson that you had to plug in, with a light on the top and a funny old dial with art deco numbers like a sunburst behind it. I would glue my ear to the tiny speaker, listening to crooners and the big band singers and whatever music was popular at the time. Blues and jazz and rock were yet to come . . .

On summer evenings, a drum-and-bugle corps would practice in the parade ground just beyond the woods. These men, the Caballeros, would gather after work. They were just starting out and couldn’t afford uniforms, so they wore big navy-surplus bell-bottoms, white shirts, and Spanish bolero hats. They only knew how to play one song, which was “Valencia.” They would march back and forth all evening and sometimes they would dance, and you could hear the music drifting up from out of the woods. My room was up in the eaves of the house with little dormer windows, and I would sit on the floor with the windows open and listen. My mother would say, “If I hear that song one more time, I’m gonna scream!” But it was brass and snare and loud and I loved it.

There were so few distractions then, before I started school, and I had so much time for daydreaming. I remember having psychic experiences as a little girl too. I heard a voice from the fireplace talking to me, telling me some kind of mathematical information, I think, but I have no idea what it meant. I would have all sorts of fantasies. I fantasized about being captured and tied up and then rescued by—no, I didn’t want to be saved by the hero, I wanted to be tied up and I wanted the bad guy to fall madly in love with me.

And I would fantasize about being a star. One sun-drenched afternoon in the kitchen, I sat with my aunt Helen as she sipped at her coffee. I could feel the warm light playing on my hair. She paused with the cup at her lips and gave me an appraising stare. “Hon, you look like a movie star!” I was thrilled. Movie star. Oh, yes!

When I was four years old, my mom and dad came to my room and told me a bedtime story. It was about a family who chose their child, just like, they said, they had chosen me.

Sometimes I’ll catch my face in a mirror and think, that’s the exact same expression my mother or father used to have. Even though we looked nothing like each other and came from different gene pools. I guess it’s imprinted somehow, through intimacy, through shared experience over time—which I never had with my birth parents. I’ve no idea what my birth parents look like. I tried, many years later, when I was an adult, to track them down. I found out a few things, but we never met.

The story my parents told me about how I was adopted made it sound like I was someone special. Still, I think that being separated from my birth mother after three months and put into another home environment put a real inexplicable core of fear in me.

Fortunately, I wasn’t tossed into God knows what—I’ve had a very, very lucky life. But it was a chemical response, I think, that I can rationalize now and deal with: everybody was trying to do the best they could for me. But I don’t think I was ever truly comfortable. I felt different; I was always trying to fit in.

And there was a time, there was a time when I was always, always afraid.

2 (#ulink_3c2dac46-c13e-59e2-a4a5-a27ea71fd9c8)

Pretty Baby, You Look So Heavenly (#ulink_3c2dac46-c13e-59e2-a4a5-a27ea71fd9c8)

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

One visit, when I was a baby, my doctor gave me a lingering look. And then he turned in his white coat, grinned at my parents, and said, “Watch out for that one, she has bedroom eyes.”

My mother’s friends kept urging her to send my photo to Gerber, the baby food company, because I was a shoo-in, with my “bedroom eyes,” to be picked as a Gerber baby. My mother said no, she wasn’t going to exploit her little girl. She wanted to protect me, I suppose. But even as a little girl, I always attracted sexual attention.

Jump-cut to 1978 and the release of Louis Malle’s Pretty Baby. After seeing the movie, I wrote “Pretty Baby” for the Blondie album Parallel Lines. Malle’s star was the twelve-year-old Brooke Shields, who played a kid living in a whorehouse. Nudes scenes abounded. The movie created a firestorm of controversy regarding child pornography at the time. I met Brooke that year. She had been in front of the camera since she was eleven months old, when her mother got her a commercial for Ivory Soap. At age ten, with her mother’s consent, she posed naked and oiled up in a bathtub for the Playboy Press publication Sugar and Spice.

One time, when I was around eight years old, I was put in charge of Nancy, a little girl of four or five, whom my mother was watching for the afternoon for her friend Lucille. I was to walk Nancy over to the municipal pool, which was about two blocks from my house, and my mother was going to join us there. I guided Nancy down the busy thoroughfare that bordered the end of the town, holding her little hand for safety. It was a seriously hot day, the bright hard sun bouncing up off the sidewalk at us. We turned a corner and were about to pass this parked car, with its passenger window rolled all the way down. From inside came this voice: “Hey, little girl, do you know where such-and-such is?” A messy-looking, rather nondescript older man, with washed-out and faded hair . . . He had a map over his lap, or maybe it was a newspaper. He was asking all kinds of questions and directions, and his one hand was moving around underneath the paper. Then the paper slid off and out popped his penis. He had been playing with it. I felt like a fly on the edge of a spiderweb. This wave of panic flushed through my body . . .

I freaked and fled to the pool, dragging Nancy along, her tiny feet trying to keep up. I rushed up to my teacher, Miss Fahey, who was at the entrance, making sure that everyone had their pool pass. I was really upset, but I just couldn’t tell her about this creep showing me his penis. I said, “Miss Fahey, please watch Nancy, I have to go home,” and I ran back. My mother was beside herself. She called the police. They came screeching up to the house and my mother and I rode around town in the back of the squad car, trying to spot the pervert. I was so small, I couldn’t see over the back of the seat. I just sat there as we rode around and around, peering over the seat as best I could, my heart pounding and pounding.

Well, that was an awakening. My first indecent exposer, although my mother said there were others. Once, we were stalked at the Central Park Zoo by a man in a trench coat who kept flapping it open. Because of their frequency, over time, these kinds of incidents started to feel almost normal.

For as long as I can remember I always had boyfriends. My first kiss was given to me by Billy Hart. How sweet to be initiated by a boy with such a name. I was stunned, alarmed, angry, pleased, excited, and enlightened. Maybe I didn’t realize all of this at the time and I probably couldn’t have put it into words; nevertheless, I was confused and conflicted. I ran home to tell my mother what had happened. She gave me a mysterious smile and said it was because he liked me. Well, up to that point I had liked Billy too, but now I was embarrassed and got all shy around him. We were very young, maybe five or six years old.

And then there was Blair. Blair lived up the street and our mothers were friends, so he and I sometimes played together. This one time, we went up to my room and we ended up sitting cross-legged on the floor, Indian style, facing each other and taking a good look at each other’s “things.” This was innocent too. I was about seven and he was maybe eight and we were curious. I’ve always been curious. Well, Blair and I must have been quiet for too long because our mothers came in and we got caught. They were more embarrassed than angry, being longtime friends, but Blair and I were never encouraged to play with each other again.

My parents held to traditional family values. They stayed married for sixty years, holding on through all the ups and downs, and they ran a tight ship at home. We went to the Episcopalian church every Sunday and my family was very much involved in all the church activities and its social life. Which may have been why I was in the Girl Scouts and was definitely why I was in the church choir. Fortunately, I really enjoyed singing, so much so that I won a silver cross when I was eight for “perfect attendance.”

I guess it’s not really until you approach your teens that you get all these doubts and questions about religion. I must have been twelve when we stopped going to church. My father had had a big falling-out with the rector or the minister. Anyway, by that time I was in high school and probably much too busy to go to choir practice.

I hated the whole process of arriving at a new school. It wasn’t the school itself. It was just a little local school, fifteen or twenty kids in each grade, and I wasn’t afraid of studying; I’d learned the alphabet before kindergarten. First, for some reason, I would get incredibly anxious about being late. Maybe I needed approval that badly. However, my bigger problem was separation—being separated from my parents. Abandonment. It was traumatic. I would be a nervous wreck. My legs would turn to jelly and I struggled to climb the stairs. I guess somewhere in my subconscious, a scene was playing on a loop of a parent leaving me somewhere and never coming back. That feeling never really went away. To this day, when the band separates at the airport and we all go our different ways, I still get that gut reaction. Separation. I hate parting with people and I hate goodbyes.

Things were changing at home. At the age of six and a half, I had a baby sister. Martha was not adopted; my mother gave birth to her after a really rough pregnancy. Around five years before she adopted me, my mom had had another baby girl, Carolyn, premature I think, who died of pneumonia. There was a boy too, whom she miscarried. Then a drug came along that helped her go to term. Martha was premature, but she survived. My father said her head was smaller than the palm of his hand.

You might have thought that the arrival of another pretty baby in my house—and one that actually came from my mom—might have triggered my insecurity and abandonment fears. Well, at first I was probably a little disturbed by not being the complete focus of all my mother’s attention, but more than anything else I loved my sister. I was always very protective of her because she was so much younger than me. My father called me his beauty and my sister his good luck, because when she was born his fortunes changed.

Sean Pryor

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

I scared my parents one morning. It was probably the weekend and they were sleeping in a little bit. Martha had woken up and was crying for her bottle. So, I slipped down to the kitchen and heated up the bottle, which I had watched my mother do so many times, and I brought it upstairs and gave it to her. My parents freaked when they discovered what I was up to, convinced that I was scalding her. But there Martha was, happily chomping down on that nipple . . . So, I found myself with a new job, which became my morning contribution to all the many routines in our Hawthorne home.

Hawthorne was the center of my universe then. We never left. I didn’t understand about finances as a young child and I didn’t grasp that there wasn’t much money and my parents were trying to save up to buy a house. All I knew was that I had a powerful yearning to travel. I was so curious and restless all the time. I loved it when we would all pile into the car and drive to the beach on our vacations, which almost always meant visiting family.

One year—I must have been eleven or twelve—we went on vacation to Cape Cod. We were staying in a rooming house with my aunt Alma and uncle Tom, my dad’s brother. My cousin Jane was a year older than me and we had lots of laughs, giggling and playing together. One particular day, while our parents were downstairs, we sat in front of the mirror fixing our hair, as we loved to do. But this time, we called down and said we were going for a walk. As soon as we were far enough away, we took out our stolen pile of lipstick and eye makeup and carefully transformed ourselves into these hot-looking babes. We probably looked like two nubile characters from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. We stopped at a stand to buy some lobster rolls, then strolled on down the street, admiring our reflections in the shop windows. But we weren’t the only ones admiring ourselves: these two men approached us and started to come on to us. They were way, way older than us. Both in their late thirties, we would discover. Pretending to have no idea that we were actually preteens, they invited us out that night and said they’d meet us at our place. Of course, we were not going to tell them our address, but we played along and said we’d come back and meet them somewhere else.

That night, our faces scrubbed clean, we were in bed playing cards and wearing our baby-doll pajamas when there was a knock on the door. It must have been eleven o’clock. Without our noticing, the two guys had followed us home and they were there to pick us up. I think by then our parents had enjoyed a few cocktails and they just thought it was hilarious. So, they threw open the bedroom door and there we were, children. It turned out that we didn’t get into too much trouble. It also turned out that one of our suitors was a very famous drummer, Buddy Rich. I later discovered that, besides being a close friend of Sinatra’s, Buddy had been married at the time to a showgirl named Marie Allison. They remained together until his death from a brain tumor at age sixty-nine, in 1987. Shortly after his visit, a large envelope arrived in the family mailbox. Inside was an autographed, eight-by-ten black-and-white glossy of my Buddy, who was once hailed as “the greatest drummer who ever drew breath.”

Interestingly, Buddy Rich returned as a presence in my life decades later, when some of my close colleagues in the British rock scene—like Phil Collins, John Bonham, Roger Taylor, and Bill Ward—would count Buddy as their greatest influence . . . My life has so often circled back on itself in these intricately obscure ways.

There was a whole lot going on that year, now that I look back on it. It was the year I made my stage debut. It was a sixth-grade school production of Cinderella’s Wedding. They didn’t give me the part of Cinderella, but I was the soloist who sang at her wedding to the prince. The song I sang was “I Love You Truly,” a big ballad featured in the movie It’s a Wonderful Life. When I came onstage I had the worst stage fright—all those eyes staring at me, kids, teachers, parents; my mom and dad were there with my sister, Martha. But I pulled it together. I just wasn’t a natural performer or a big personality. I think I had a big personality inside, but I didn’t have one on the outside; I was very shy. Whenever the teacher would come up to me and say, “You were so good!” my misfit mind added an unspoken, “Not really, have you lost your mind?”

My experience with ballet wasn’t really much better. Like a lot of little girls, I wanted to be a ballerina. I’d been exposed to Margot Fonteyn and other wonderful dancers by my mother, who’d had a cultured childhood and wanted me to have some of that experience. But in ballet class I always felt very self-conscious because I was convinced I was too fat, which I wasn’t at all. I had an athletic body. But I wasn’t birdlike and delicate like all the little girls who looked so cute and perfect and like each other in their little tutus. I felt that I fucked the whole thing up by being so chubby and standing out.

The biggest thing that happened that year was that my family finally bought that little house and we moved. Our new neighborhood was not much different from our old one and it was not very far away. But it was in another school district, which meant that I had to switch schools. It was not easy being the new kid in sixth grade. I didn’t know anybody there, apart from two girls I knew from Girl Scouts. I had no friends. Even more startling, Lincoln School had a whole different curriculum, which was much more focused on academics than my old school, so I had a lot of work to do to catch up. But there was a silver lining to this very dark cloud, I told myself. Which was: no more Robert.