По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

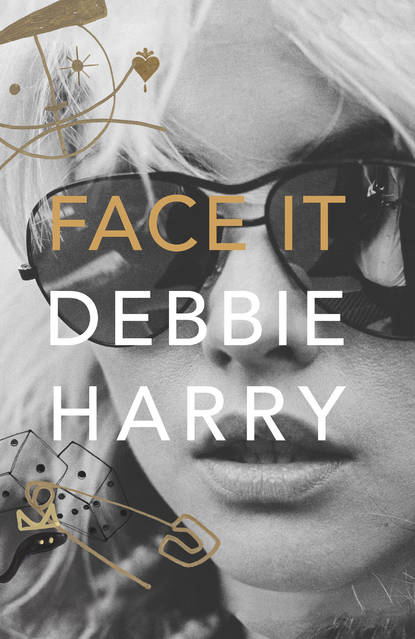

Face It: A Memoir

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Then I saw a blind ad in the New York Times looking for a secretary. It turned out to be for the British Broadcasting Corporation. This was my first link to what would become a long, lovely relationship with Great Britain. They gave me the job on the strength of the sensational letter that my uncle helped me write. Once they had me, they realized that I wasn’t very good at what I was supposed to do, but they kept me anyway and I grew into the job. I learned to operate a telex machine. I also met some interesting people—Alistair Cooke, Malcolm Muggeridge, Susannah York—who came into the office/studio for radio interviews.

Plus, I met Muhammad Ali. Well, not exactly met him. “Cassius Clay is coming in to do a TV interview,” they said, so I snuck around the corner and wow, I saw this big, beautiful man walk into the TV studio and close the door. It was a soundproofed room with a small window way up high, so I decided, being athletic, that I was going to grab the windowsill and pull myself up and watch the taping. But, as I pulled myself up, my feet kicked the wall with a thud. In a flash, Ali’s head whipped round and he stared right at me. He nailed me and I was transfixed. He’d responded with the animal instinct and lightning reflexes of the supreme champion he was . . . I quickly dropped down to the floor, shocked and excited by the primal exchange. I could have gotten into trouble, particularly if they had already started to record, but fortunately no one else in the room had even noticed.

The offices for the BBC New York were in the International Building at Rockefeller Center, directly across from the monumental St. Patrick’s Cathedral. When I was working at the BBC, I believe Fifth Avenue was a two-way street, and the traffic was immense. A block south of the cathedral was Saks Fifth Avenue. In front of the International Building was and still is the enormous bronze statue of Atlas holding up the world. Behind it is Rockefeller Plaza, where the skating rink and the big Christmas tree are located during the holidays. During the summer the rink becomes an outdoor café. Directly behind the rink is the NBC building, with the Warner Bros. offices nearby too.

Strolling past the store windows and through the canyons of buildings was always interesting, and I made it a point to go over to visit one of my favorite characters, “Moondog.” This tall, bearded old man with his horned Viking helmet was a vision. He stood on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifty-Third in his long reddish cape holding his spearlike pole, selling booklets of his poetry. Moondog now has his own Wikipedia page, but back then few people who walked past him knew who the fuck he was. Most people steered clear of or didn’t even notice him—just another crazy “weirdo” to avoid or blank out.

Some thought he was an eccentric, blind, homeless man, but he was much more. Moondog was also a musician. He had an apartment uptown but kept his image and his privacy closely guarded. He designed instruments and also recorded, and he became adored by most New Yorkers. A beloved fixture, a true New York character who sometimes recited his poems to the businessmen and tourists hurrying past him. He was freaky but he was fondly called the Viking guy—even if no one knew about all his artistic achievements.

And then there were the more sinister types: the silent men in black selling small newspapers or booklets. They were serious, intense, kind of scary, which made them all the more intriguing, of course. They called themselves “the Process”—short for the Process Church of the Final Judgment—and were scary but compelling in their intensity. Never alone, they stood in groups on the midtown corners in their quasimilitary black uniforms.

Scientology wasn’t so well-known at the time, but cults, communes, and radical religious movements would come and go all the time. I wasn’t aware completely of Scientology or the Process Church, but I respected the commitment it took for these guys to stand and deliver in midtown to a straight bunch of bros. They roamed around downtown as well, among much more sympathetic audiences in the West and East Village.

It was a business, it was a religion, it was a cult; maybe it still is but I don’t think they call it the Process anymore.

I had come to the city to be an artist, but I wasn’t painting much, if at all. In many ways I was really still a tourist, just experiencing the place, having adventures, and meeting people. I experimented with everything imaginable, attempting to figure out who I was as an artist—or if I even was one. I sought out everything New York had to offer, everything underground and forbidden and everything aboveground, and threw myself into it. I wasn’t always smart about it, admittedly, but I learned a lot and came out the other side and kept on trying.

Drawn to music more and more, I didn’t have to go far to hear it. The Balloon Farm, later called the Electric Circus, was on my street, St. Mark’s Place, between Second and Third. The old building the shows were held in had some serious history: from mob hangout, to Ukrainian nursing home, to Polish community hall, to the Dom restaurant. The whole neighborhood was Italian, Polish, and Ukrainian. Every morning, on my way to work, I would see the women in babushkas with their buckets of water and brooms, washing the sidewalks clean of whatever went on the night before. A ritual carryover from the old country.

Trying to keep time at the Mudd Club.

Allan Tannenbaum

One evening, as I walked past the Balloon Farm, the Velvet Underground was playing, so I went inside and into this brilliant explosion of color and light. It was so wild and beautiful, with a set designed by Andy Warhol, who was also doing the lights. The Velvets were fantastic. John Cale brilliant, with his droning, screeching electric viola; proto-punk Lou Reed with his hypercool, drawling delivery and sneering sexuality; Gerard Malanga, gyrating around with his whip and leathers; and the deep-voiced Nico, this haunting, mysterious Nordic goddess . . .

Another time, I saw Janis Joplin play at the Anderson Theater. I loved the physicality and the sensuality of her performance—how her whole body was in the song, how she would grab the bottle of Southern Comfort on the piano and take a huge slug and belt out her lines with crazed Texan soul. I’d never seen anything like her onstage. Nico had a very different approach to performing; she just stood there, still as a statue, as she sang her somber songs—much like the famed jazz singer Keely Smith, with the same stillness but a different kind of music.

I would go see musicals and underground theater. I bought Backstage magazine and I’d take notes on all the auditions and then join the endless lines of hopefuls who, along with me, never got past first base. There was also a strong jazz scene on the Lower East Side with haunts like the Dom, the renowned Five Spot Cafe, and Slugs’. At Slugs’, in particular, you’d get to hear luminaries like Sun Ra, Sonny Rollins, Albert Ayler, and Ornette Coleman—and find yourself at a table next to Salvador Dalí. I met a few of the musicians. I remember showing up and sitting in on a couple of loose, “happening”-like gatherings, the Uni Trio and the Tri-Angels—free, abstract music where I sang a bit or chanted and banged some percussion instrument or other. That was the same thing we did in the First National Uniphrenic Church and Bank. The leader was a guy from New Jersey named Charlie Simon who later christened himself Charlie Nothing. He made sculptures out of cars that he called “dingulators” that you could play like guitars. He also wrote a book called The Adventures of Dickless Traci, a detective novel with a weird sense of humor, but that was later. He was multidimensional in music, art, and literature—a free spirit who was more beat than hippie. And he made me curious. I liked the curiosity because I was curious myself. If any other guy had come along and played me a track from a Tibetan temple with men giggling and growling in the background, I would have liked him too.

The sixties were the age of happenings. It was also the time of a great New York loft scene where so many of these wonderful parties and happenings took place. The lofts down below Canal Street and in Soho were former manufacturing spaces and most were illegal living, but they were very cheap, $75 or $100 a month, so all the artists rented these enormous two-thousand-square-foot spaces. That’s where we played our anti-music music. Charlie played saxophone. Sujan Souri, a jolly, Buddha-bellied Indian man who was a philosophy student, tapped away on the tablas, and Fusai, a countrywoman to Yoko Ono, sort of sang in a very high voice. I don’t know if I banged sticks together or screamed; probably both. Our drummer, Tox Drohar, was wanted for something somewhere—and I surmised he was hiding out, which forced him to change his name and disappear. And then he left to go live with his girlfriend in a little shack in the Smoky Mountains on the great Cherokee reservation.

My boss at the BBC told me I had two weeks’ vacation. I wasn’t allowed to choose the dates and they gave me two weeks in August. It was the hottest, most awful time of summer. Phil Orenstein was an artist working in plastic who made inflatable pillows, furniture, and bags with silk-screened paintings on them. He needed help assembling the straps on some of the bags. So, there I was, in this little plastics factory, tying knots and cutting the ends off with a hot knife. But the fumes from the plastic in that heat were unbelievable. I was seeing spots. I think I lost a piece of my mind from doing it.

But I had those two weeks off, so Charlie Nothing and I decided to take my saved-up $300 and go visit Tox and his very, very pregnant girlfriend, Doris, in Cherokee, North Carolina. We drove down and stayed there for a week and managed to spend my $300. I went back to the BBC covered in mosquito bites, still seeing spots from the plastic fumes and too much pot. But it was a fair exchange: the Smoky Mountains were magnificent and I would have never gone to Cherokee on my own and sat around in rocking chairs with old-timer Indians as they chewed tobacco and spat juice into paint cans.

In 1967, the First National Uniphrenic Church and Bank released an album, The Psychedelic Saxophone of Charlie Nothing, on John Fahey’s record label Takoma. But I had left by then. I also quit the BBC, which I felt was too time consuming. I got a job at Jeff Glick and Ben Schawinski’s Head Shop on East Ninth Street—the first-ever head shop in New York City. Pipes, posters, bongs, black-light bulbs, tie-dyed T-shirts, incense, the usual stuff, only then it was unusual. Right next door was a peculiar storefront with filthy windows plastered with button cards yellowed from age. The crone who had the store lived in the back. Wrapped in her shawl, she looked like an image from a fairy tale. Veselka, which translates to “rainbow,” is a no-frills, twenty-four-hour-a-day Ukrainian eatery next door. When the old woman eventually died they incorporated her store, enlarging their restaurant. The Head Shop was just around the corner from my apartment on St. Mark’s place, so no commute, and it was fun. All the downtown people, the uptown people—in fact, everyone—came in there and it was a really good scene. The Head Shop was an ideal place to meet people who were looking to break some rules.

Ben’s father was a Bauhaus painter and Ben was a sculptor, furniture designer, and builder, easygoing, very cute, and a ladies’ man. We had started going out and we were pretty interested in each other. Eventually he met these guys from California who had a commune, in Laguna Beach I think. He made all these plans to move out there and be with these people and he wanted me to go with him. I really liked him, but I couldn’t drop everything and blindly follow him. I was still working on music and I was really upset that he wanted me to just throw everything away and go with him. For a while I didn’t know if I had made a mistake or not. Well, a few years later he ended up coming back. He’d had this very fancy Volkswagen bus that he had fitted out beautifully—but as soon as he got out there the van sadly got lost in a mudslide.

One day two handsome, long-haired leather boys strode into my domain—two rebels without a cause. These pierced puppies pressed up against the counter, asking to buy rolling papers and flirting like crazy. I liked the older one, whose name I can’t remember now because he was sweet natured, on the shy side, easy to talk to. The other one, the intense one, just stood staring at me, adding the occasional quip, trying to be funny. That one’s name was Joey Skaggs. Joey came back to the shop a few days later without his friend. It was Valentine’s Day and he had come to see the girl with the heart-shaped lips.

He invited me over to his big funky loft on Forsyth Street below Houston. Joey was truly a man for all seasons. He had three bikes that he kept upstairs, real heavy-duty motorcycles, one of them a Moto Guzzi, one of them British; how he got them up those stairs I don’t know. He was also a performance art hustler. One of his more famous shows was on Easter Sunday in Central Park’s Sheep Meadow, when he carried a gigantic cross on his back and dragged it around the park during a peace rally. He had that Christlike look with his long hair and thin body, though the leather pants and biker boots were a bit of a stretch. He made the papers posing atop a large boulder at the edge of the field, draped with his cross, à la Christ on the way to Golgotha.

Joey had a friend who was a filmmaker. I can’t remember his name either, but he was very handsome. One day Joey invited me over and when I walked in, Joey grabbed me and started tearing off my clothes, kissing me, fondling my breasts, playing with my pussy. Then he threw me down on his bed. He got me really hot and I reached to yank off his pants. But he wouldn’t let me. He backed off, stood up, and out from the shadows slunk this dude with a movie camera. There I was, naked, spread, and very wet—and suddenly this thing, this all-seeing eye, is wiggling toward me, voyeur attached. Well, that was a rush. I felt shocked, furious, betrayed, and disrespected, but I was also very turned on. I wanted to knock his teeth in and fuck him at the same time. Scream, cry, get dressed, or go for it? I tried to be cool, silly me. I finally climbed onto a small pedestal and posed like a statue. All of this is on film somewhere. Don’t ask me what happened to the footage. Absorbed into the cosmic ether of the sixties, I suppose.

This was all pretty typical for Joey, actually, who’s maintained himself as a professional media prankster ever since. I’ve had a few laughs at his antics over the years: his fake ad for a dog brothel, which got covered by ABC and won them an Emmy; his Hair Today company, which marketed a new kind of hair implant—using whole scalps from the dead; his fake SEXONIC sex machine, which he claimed had been impounded at the Canadian border; his Bullshit Detector Watch (which flashed, mooed, and shat). And so much more . . .

I can still remember Joey’s loft. That part of the Lower East Side wasn’t gentrified at all in the sixties; it was Alphabet City, gangland, dangerous. So, whenever I went there, after turning the corner off of well-lit Houston onto dark and narrow Forsyth, I’d run down the street and into the building and up those wooden stairs, the darkest, scariest staircase of them all, and I’d arrive at Joey’s breathless from running and climbing. He probably thought I was just hot for him and couldn’t wait. Which was also true.

Then Paul Klein, the husband of a very close friend of mine from high school, Wendy Weiner, invited me to join them in making some music. We would sit around and sing songs together and I would harmonize. It began casually but eventually evolved into a band, the Wind in the Willows, named after the classic children’s book by Kenneth Grahame. I got the job, for what it was worth, as backup singer. Wendy and Paul were Freedom Riders who went to Mississippi to register black people to vote. Stokely Carmichael, who was the organizer of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, told them, “You can’t share a room in Mississippi without being married and expect not to be arrested,” and so they got married. When they came back they moved to the Lower East Side and we resumed our friendship. I knew I wanted to be a performer—I was still vague on what kind, but at least I knew that.

Paul was a bearded, folky, big bear of a man. He sang and played a little guitar and he was another likeable hustler. It was the age of everyone looking for the golden opportunity and in the midsixties, record companies were working their own major game: so loaded with cash, they’d put bands up in houses and give them money to live on and to record. A kind of patronage system. And if the music didn’t sell, then fine, they had an excuse for a write-off.

Traffics in Saccharine Details

Painting by Robert Williams

The Purposed Mysteries, Fears and Terrifying Experiences of Debbie Harry

Remedial title: The Jersey Towhead Who

Eventually there were eight or nine people in the Willows after Paul kept adding and adding. Peter Brittain, who also played guitar and sang, was married to another of my closest friends since childhood, Melanie. There was a double bass player, Wayne Kirby, who was from Paterson, where both my grandmothers lived, and had left to study at Juilliard. There was a woman named Ida Andrews, also from Juilliard, who was a real pistol and played oboe, flute, and bassoon. We had keyboards and a vibraphone and strings. It was sort of like a small orchestra. A kind of baroque folk music but with these percussive things going on. I played finger cymbals, tamboura, and tambourine. Our producer Artie Kornfeld also played bongos. More famously he went on to create the Woodstock Festival with Michael Lang. We had two drummers, Anton Carysforth and Gil Fields. There was also a very sweet and good-hearted man named Freddy Ravola, whom we called our “spiritual adviser,” because of his positivity. He worked as our roadie. Not that we did many shows.

In the summer of ’68 we released our debut album, Wind in the Willows. It was my first time on a record. I sang lead on one song, “Djini Judy,” but aside from that I was like wallpaper, something pretty to stand in the back in my hippie clothes and with my long brown hair parted in the middle, going “Oooooo.” Artie Kornfeld, who produced the album, was working at Capitol Records as their “vice president of rock” and seemed to have boundless company money to spend on us. It was not a quick album to make. Apparently, Capitol was going to give us a big push. All I can recall is playing one big show in Toronto, opening up for a Platters cover band, the Great Pretenders, or something like that. But what I do clearly remember is Paul encouraging all the band members “to get closer to each other” with some helpful doses of acid and free love. Ha! Nice ploy. But I did not drink the Kool-Aid.

I did go to Woodstock with my friend Melanie and her husband, Peter, and that was a massive mud pit. Torrential rain. People were covered with mud and jumping into the stream to wash it off. So, we bailed and moved our tent to higher ground. Which was great, until we were forced to move again in the middle of the night, to make room for a helicopter landing place.

I remember there was this group called the Hog Farm from San Francisco who set up a soup kitchen and they were feeding everyone, and I do mean everyone. Hundreds of thousands of people. Amazing. I just walked around on my own, seeing all the people, meeting some of them, watching bands, and waiting for Jimi Hendrix to play.

I quit the Wind in the Willows. I enjoyed performing; I even wrote something for the second album entitled “Buried Treasure.” The album was never released and apparently the tapes are lost. I wouldn’t bother looking for them. I left because of big musical differences and bigger personal differences and because the band never played. And I wasn’t in control, I was just a decorative asset in the band and I outgrew it. And I knew that I wanted to do something that was more rock.

When the Wind in the Willows and I parted company, I moved in with the last drummer that was in the band, Gil Fields. He was a strange-looking guy with a great big Afro and startling blue eyes. He was completely bonkers but an incredible drummer, a prodigy who had been playing drums since he was four years old. I gave up my apartment on St. Mark’s Place and decided to get rid of everything and just have one suitcase of belongings and a tamboura and a tiny TV that my mother had given me. I moved into Gil’s place at 52 East First Street. I needed a job and it was Gil who suggested I try to get a job at Max’s Kansas City. He said, “Well it’s this place where everybody hangs out, Max’s, have you heard of it?” “No.” “Well it’s up on Park Avenue South right near Union Square.” I had never really worked as a waitress before, except in a diner in New Jersey when I was in high school. But the owner, Mickey Ruskin, gave me a job.

The very first time I did heroin was with Gil. He was nervous and hyperthyroid and excitable—he was a wreck. If ever there was anybody that needed heroin, it was Gil. I remember his tapping out this tiny little line of gray powder. And we snorted it up. And I felt a kind of rush I’d never felt before. And I thought, Oh, this is so nice, so relaxing, aah, I don’t have to think about things, and it was so delicious and delightful. For those times when I wanted to blank out parts of my life or when I was dealing with some depression, there was nothing better than heroin. Nothing.

Max’s Kansas City was the place to be seen. That was another fabulous time in New York, no end of creativity and characters, and most of downtown seemed to wind up in Max’s. I worked the four-till-midnight shift and other times seven thirty until it closed. James Rado and Gerome Ragni would be in the back room every afternoon, writing the musical Hair. Little by little, as the day turned into night, the crowd got wilder and freakier. Andy Warhol would always come in with his people and take over the back room. I saw Gerard Malanga and Ultraviolet, who had been Salvador Dalí’s lover and was now a Warhol superstar; Viva, another Warhol superstar; Candy Darling, a stunning transgender actress; the flamboyant Jackie Curtis; Taylor Mead; Eric Emerson; Holly Woodlawn; and so many others. Whatever you were doing, you couldn’t help but stop and stare at Candy. Edie Sedgwick was around sometimes, and Jane Forth, another of the Factory’s It Girls.

There were Hollywood stars too—James Coburn; Jane Fonda. And rock stars—Steve Winwood; Jimi Hendrix; Janis Joplin, who was lovely and a big tipper. So many of them. I served dinner to Jefferson Airplane two days before they left for Woodstock.

And then there was Mr. Miles Davis. He sat back against the banquette along the outside wall upstairs, like a black king. No way he could have known this little white waitress was a musician too—and maybe she didn’t know either at that point . . .

Why did they seat him in my section—not the one at the end of the earth but the one on the other side of the moon? The section that overlooked what often became the stage, late at night. The tables against the wall were slightly raised on a low step-up platform. He came there with a stunning white woman, a blonde as I remember.

I came up to their table in my little black miniskirt, my black apron, and my T-shirt, with my long hippie hair au naturel—limping from a terribly infected foot injury. The blister and my slashed Achilles were so painful I had to wear these clunky backless sandals which were absurd for work, but I was young enough that it didn’t matter.

Would they care for drinks? She spoke, he was silent, still as a dead calm, statuesque with his ebony skin shining softly in the dim red light of the upstairs back room. He had his own light, glowing, shimmering, alive with his thoughts. Would they like to eat? He remained silent while she ordered for both of them. I don’t know if he ate his dinner. I couldn’t bring myself to watch him chew, but I did see him bend forward as if to take a bite of his steak.

At about this time, it started to get busy and I had to keep limping along—and couldn’t indulge in watching Miles having dinner on a two-top, upstairs at Max’s. Why the hell they sat him up there, I’ll never know.

All these people, all doing in their own way what I had dreamed of doing and had come here to do—and I was waiting on them. It was frustrating but helpful in a way, because I was on shaky ground back then, probably hypersensitive to criticism, and I guess it helped toughen me up. It was hard work physically and some days were rougher than others, but I think it was one of the best times of my life, all in all. Very colorful.

But Max’s was about more than just bringing people food or cocktails; it was all such a big flirtation, such a scene. Everybody who went there was checking out everybody else. One night, I did Eric Emerson, upstairs at Max’s, in the phone booth. My one-hour stand with a master of the game. Eric was one of the Warhol superstars and he was just striking—a musician in a muscular dancer’s body. After watching him dance and bound in one leap across the stage at the Electric Circus, Warhol cast him in Chelsea Girls. I was one of many who had flings with Eric. He was a piece of human art. He had such intense energy and fearlessness and he had more children than he could keep track of. He was also pretty stoned out.

Everybody on the scene did drugs. That’s how it was back then, part of your social life, part of the creative process, chic and fun and really just there. No one thought about the consequences; I can’t remember if any of us even knew the consequences. It may sound strange when you’re talking about drugs, but it was a more innocent time. They weren’t doing scientific studies and setting up methadone clinics; if you wanted to do drugs you did drugs and if you got hung up or got sick, you were on your own. Curiosity was a big factor too—drugs were another new experience to check out.

There was this man who came into Max’s one time—it was late afternoon—Jerry Dorf. He was an older guy, very handsome, and there were all these pretty girls around him. He was flirting with me like mad. So, we got to talking and I think I was complaining about working at Max’s, so he said, “Well, why don’t you come with me to California? You can stay at my house in Bel Air.” Ha! Another man who wants me to drop everything and go with him to California. “Oh no,” I said, “I’m not so sure about that.” At that time I had a sitar and I was studying a bit with my teacher, Dr. Singh. But Jerry and I started fooling around. He was loaded. He bought me some clothes from Gucci. “You have to dress well to travel,” he said.

I quit my job at Max’s abruptly—which Mickey Ruskin never forgave me for; he was very pissed at me because by that point I had become one of his better waitresses—and I went with Jerry. I stayed in his house, but I never felt comfortable. It wasn’t even a month, but it seemed like forever. Then Jerry’s girlfriend found out that I was living there. She had run away with a rock band, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and was living with them in the desert, but now came running home. So I got moved over into the Hotel Bel-Air. It was nice, but I was lonely. I know a lot of people in Los Angeles today, but I knew no one then. So I said to Jerry, “Put me on a plane, I want to go home.” When I was back, I got back with Gil and I went to Max’s and asked Mickey for a job. “No way,” he said. So that’s when I became a Playboy bunny.