По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

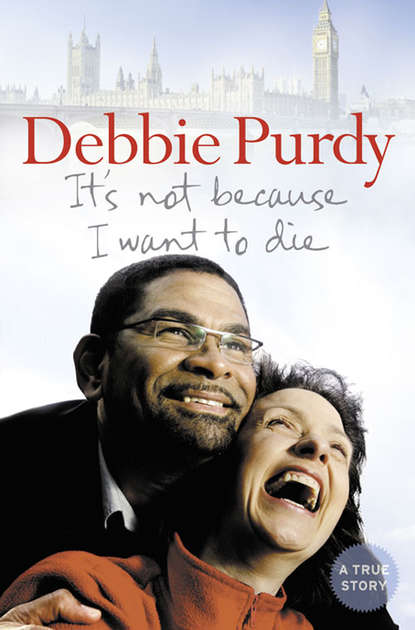

It’s Not Because I Want to Die

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No, not really. I’m fine, thanks.’ I realised I didn’t want Omar to see me on a date. I had been proclaiming disinterest

for a couple of weeks, but my reluctance to let him see me with another man spoke volumes and I had to admit, to myself at least, that this charming enigma was burrowing his way under my skin.

My date came over to sit beside me and slipped his arm around my shoulders. Immediately I jumped up. ‘Must go and chat to someone,’ I gabbled. ‘I’ll be back in a minute.’

The poor man didn’t know what was going on. Every time he tried to lay a finger on me, I’d quickly check whether we were in Omar’s line of sight from the stage, and if we were I’d jump up manically and find someone else to talk to. I made sure we weren’t alone, inviting everyone I knew to join us at our table. By the end of the evening my poor date had certainly got the message that I wasn’t interested in him romantically – either that or he had concluded that I was deeply neurotic.

I didn’t talk to Omar that night because he was working and we’d left by the time he came off stage, but several times I saw him watching me with a confused expression. For my part, that was the night I finally accepted that I was hugely attracted to him. Latin musician or not, I was going to have to go out with this man. It didn’t look as though I had a choice.

The next day when I got home from work at the adventure travel company, Belinda said to me, ‘You’ll never guess what! He called. Several times.’

‘Omar? He called here? What did he say?’ Belinda didn’t speak any Spanish either, so I knew it couldn’t have been a long chat.

‘He said, “Party. Tonight,” and he left the address. That was all.’

A mutual friend of ours was having a party that evening and Omar had phoned to make sure I would be there. I think I blushed I was so pleased. ‘What do you reckon?’

‘Oh, Debbie, for goodness’ sake, just go for it and save us all the hassle. Please.’

I grinned. That’s exactly what I planned to do.

The party was at the home of an American guy and he’d set up a barbecue on his balcony. It was late when I got there and the main room was heaving with people. I stood in the entrance, peering around to see who I knew, and locked eyes with someone staring straight back at me: Omar. He hurried over.

‘You came,’ he said in English. ‘That’s good.’

He got me a drink and Rolando came over to translate for a while so we could have a slightly more sophisticated conversation than our usual monosyllables. When Omar went to the barbecue to get some food, I took the opportunity to ask Rolando a question that had been on my mind: was Omar married? I pointed at Rolando’s wedding finger and motioned a ring. He shook his head, but I wanted to double-check, given my distrust of Latinos, musicians and men in general, so I asked Rolando directly.

He frowned and scratched his cheek before saying, ‘I’m not sure. He’s never mentioned anything about a wife. We just play together. We aren’t close. Sorry – I can’t help you there.’

I later found out that Omar and Rolando had been best friends for fifteen years and knew all there was to know about each other. Rolando hadn’t wanted to answer my question in case he contradicted something that Omar had told me, so he’d just avoided it. It was the same for all the band members: they would have laid down their lives for each other. They were a long way from home, and they depended on each other, so economy with the truth over romantic interludes was second nature. It was behaviour like this that gave Latin musicians their reputation (but they also have a reputation for steadfast loyalty, and that’s true as well).

I circulated, chatting to people I knew, while Omar hovered by my side doing his bodyguard impression. As the party broke up, we went back to Harry’s Bar and I knew that I was happy with Omar beside me. Everyone was watching us and wondering, Will they? Won’t they? because his pursuit of me was good gossip in our orbit.

In the early hours of the morning he walked me home to my flat and I was amused because he did that gentlemanly thing of constantly moving so that he was between me and the road. I tried to explain to him that the tradition derived from days when ladies didn’t want their beautiful gowns to get splashed by passing carriages, which was hardly likely to be a problem in modern-day Singapore. First of all, I had left my beautiful gown at home, and secondly, the roads were bonedry. I’m not sure he understood my explanation, delivered in a mixture of French, English and sign language, like an elaborate game of charades.

Shortly after that he kissed me for the first time, which was nice. More than nice. He remained a perfect gentleman, though, dropping me back at the flat I shared with Belinda and Tetsu, and asking if he could see me the next evening. He gave me his phone number and taught me how to greet the person who answered the phone: ‘Quiero hablar con mi mulato lindo.’ I repeated the phrase until I could say it to his satisfaction, and we kissed one last time before he headed off down the road, turning to give me a wave as he left my sight.

He and the band members loved it when I phoned the next day – I thought I was greeting them and commenting on the wonderful day; in fact I was asking to speak to ‘my beautiful mulatto’!

Nevertheless, the next night I was right there when Omar played his set at Fabrice’s and he gazed straight at me as he sang many of the numbers. When he was introducing the band, he went through all their names, then at the end said, ‘Allì tienes a la mujer que tiene mi corazón encadenado,’ and I knew without being told what that meant. I had his heart in chains. From then on he said it every night I was there.

The evening after we’d slept together for the first time, he walked off stage in the middle of the Cuban Boys’ set and came over to kiss me, which was incredibly romantic. Our friends in the audience cheered and clapped. I blushed, because I embarrass easily, but I loved it at the same time.

Neither of us had much money, but it didn’t matter – we were living in a beautiful city, had some great friends, and both of us had jobs that we loved and would have paid for the privilege of doing. We had the added advantage of being welcome guests at most of the places we wanted to go. (It seems silly, but business is business and I was more welcome than Omar because I could publicise the venue.) We would talk in odd words and phrases we’d picked up of each other’s language, supplemented by whole sentences when Rolando or someone else was around to translate for us. After the Cuban Boys’ set at Fabrice’s, we would go for breakfast at the market or pick up some food from the 7-Eleven in Orchard Road, then walk home together in the early morning light. It was lovely, despite the fact that I sometimes had to go straight to work without any sleep.

I had a book of Chinese horoscopes in my room and Omar asked me when my birthday was, then worked out that I was born in the Year of the Rabbit, so from then on he called me ‘Rabbit’. That was his pet name for me. He was born in the Year of the Ox, so I didn’t do the same.

We had a fantastic two weeks together, full of music and city lights (and I guess the food and wine didn’t hurt the atmosphere). At the beginning of March a neurology appointment I had booked in Brighton meant I had to go to England. Omar and the band were going to Indonesia for a month to do some gigs at a club in Jakarta.

As we parted on that night in early March, he said to me, ‘See you in a month, Rabbit.’

My life was perfect. I was doing things I loved in a new and exciting city, and I’d just met someone who made the sunniest day a little brighter. I was living a dream, but I didn’t really realise how lucky I was. I took it all for granted. I guess I felt entitled to everything life could offer. As I boarded the plane, I couldn’t wait to get back and carry on living my wonderful life.

Chapter 2 Wading through Honey (#ulink_7d593648-8893-5eeb-a633-2ca1117a34f3)

The reason I had a neurology appointment was because I’d been noticing my body behaving a bit strangely over the last year or so. There were lots of little things – nothing major – but they seemed to indicate something odd was going on.

The weirdest incident had been in August 1994, when I’d collapsed in the street back in Yorkshire, where I lived at the time. I’d spent the day walking around Leeds city centre with an American friend called Greg, who was thinking of moving to the UK and wanted to explore what kind of work he might be able to get. We’d walked for miles into recruitment companies and coffee shops. Greg needed to get a feel for the city as well as the jobs. On the way back, when we were only a couple of hundred yards from my home in Bradford, all of a sudden my legs gave way beneath me and I collapsed on the pavement.

‘What’s going on? Did you trip?’ Greg stretched out an arm to help me.

‘I don’t know.’ I grabbed his hand and tried to pull myself up, but my legs wouldn’t take my weight: they were weak and unresponsive. ‘Isn’t that strange?’ I felt silly more than anything else. Greg was super-fit, and although I knew I’d been getting a bit out of condition, I hadn’t thought it was quite that bad.

‘Can’t you get up?’

‘I just need to rest a while and then I’ll be fine.’ At least, I hoped I would.

‘Try again,’ Greg coaxed me, concerned and more than a little embarrassed to be seen with a woman who was sitting in the gutter on a busy main road. People passing clearly thought I was drunk.

I summoned all my strength, clung on to Greg’s arm and tried to haul myself up, but my legs still wouldn’t support my weight. An image of the Billy Connolly sketch in which he imitates a Glaswegian ‘rubber drunk’ flashed through my head. I had rubber legs, it seemed, without a drop of booze having passed my lips.

‘It’s no use,’ I said. ‘We’ll have to call a cab.’

Greg seemed glad to be given something to do. Before long he was helping me into the back of a local cab. Two minutes later Greg and the driver got me into the house by holding me on either side and more or less carrying me until I was ensconced in an armchair in my front room.

‘You have to see a doctor,’ Greg insisted. ‘That shouldn’t happen. Shall I phone for someone?’

‘If you want to do something useful,’ I told him, ‘make a cup of tea.’ A universal British cure-all.

We sat and drank our tea and talked about the job opportunities Greg had found, and a few hours later my legs seemed to be back to normal, so I brushed aside all his nagging about doctors and tests and making a fuss. I’m an arrogant sod and prided myself on my physical prowess. I’d completed several parachute jumps, skied, played netball for my county team and learned to waterski off Hong Kong, so a day’s walking shouldn’t have fazed me.

Over the next couple of weeks, though, I gave it some more thought, wondering what was going on and whether I needed to do anything about it. I’d noticed a few other odd things. For example, I was a keen horse-rider, but now it took me quite a lot of effort to get my foot in the stirrup and swing myself up on to the horse. I’d always had a good seat, which you achieve by using your thigh muscles to hold your position on the saddle, but recently I’d been a bit like a sack of potatoes being bounced around as the horse cantered across the field.

Then there was my eyesight. I’d noticed that words were getting slightly blurred on the page. Curiously, it seemed to get worse when I was too hot. I figured that everyone’s eyesight deteriorates as they get older, but I was only 31. Should it be starting that early?

Having lived all over the world, I’d been back in the UK for almost four years before I moved to Singapore in September 1994 and I blamed the British climate for many of my symptoms. I’d put on a bit of weight, so that could have been one factor, but I mostly blamed the sedentary indoor life I’d been leading. When I was out in the Far East, I was always rushing around waterskiing, swimming or cycling. On Christmas Day we would spit-roast a turkey on the beach, decorate palms with tinsel and splash around in the surf. Back in cold, rainy Bradford, Christmas meant eating far too much, drinking more than was good for you and falling asleep in front of the TV.

I had come back to the UK in 1990 to help look after my mum. She had been ill for several years and my sisters had been shouldering the responsibility. I felt it was time that I shared it. When Mum died in 1992, it came as an incredible shock, despite the fact that we’d all known she was ill. It was nice to get close to my family again and I’d planned on staying for a bit, but I was beginning to feel old, putting on weight and generally feeling ‘not right’.

Then, in 1994, a friend of mine, a singer called Mildred Jones, called to invite me out to Singapore, where she had a contract at the piano bar in the Hilton Hotel. She said I could stay with her and she would introduce me to people who would help me to find work.

It was an irresistible offer and I took less than a nanosecond to reply. ‘Sure. I’m on my way.’

I found people to look after the house I owned in Bradford and booked a plane ticket for 24 September. Before I left, I decided to pay a quick visit to my GP just to be on the safe side.

I sat down in his surgery and let the words pour out. ‘I’ve been a bit out of sorts recently. I’m sure it’s partly grieving for Mum, but also I’ve put on some weight that I need to lose, and living in the UK doesn’t really suit me. I prefer a hot climate and an outdoor lifestyle. Anyway, I’m solving it by moving out to Singapore next week. What do you think?’

‘That all sounds very sensible,’ the doctor said, a bit bowled over by the speed at which I can talk when I get going.