По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

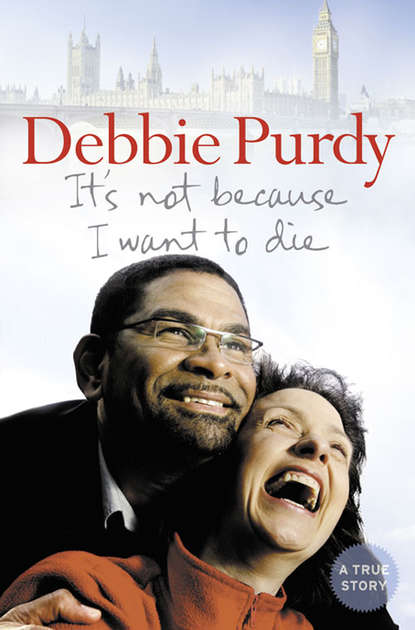

It’s Not Because I Want to Die

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘The consultant will study the images and discuss the results with you. He has to interpret them.’

I knew they had found something. They must have. Why else had it only taken a few minutes? But they wouldn’t tell me.

I was due to travel up to Yorkshire the next day to see the therapist I’d been referred to, but I rang my neurologist first.

‘Should I go to Yorkshire?’ I asked, and explained the situation.

‘No, come in to see me tomorrow morning at ten to nine, before surgery starts.’

That’s when I knew for sure that they’d found something. I spent the night imagining the worst and trying to talk myself round. My aunt and uncle drove me to the hospital the next morning and at my request they waited outside in the car park. I wanted to face this on my own.

‘So what is it?’ I asked as I sat down, more nervous than I was when I sat my O levels – and that’s saying something.

The consultant looked grave. ‘When I first saw you, I thought you had MS.’

I waited for the other shoe to drop.

‘And it is MS.’

It’s normally hard to shut me up, but I couldn’t think of a single thing to say. The consultant continued that he was going to refer me for a lumbar puncture so that he could definitely rule out a couple of other things, but said he was convinced it was multiple sclerosis. He had been pretty sure from my gait when I first walked into his office, and the MRI scan had backed up his instinct. We made an appointment to talk again after I’d had the lumbar puncture.

I left his office and walked back down to the car park, where my aunt and uncle were waiting, and still I couldn’t speak. I got into the car and stared at them wordlessly with an overwhelming sense that my life had just changed for ever.

Then I rejected it. He had to be wrong. Please, God, he simply had to be.

Chapter 3 ‘Can I Scuba-Dive?’ (#ulink_b9f8d3e3-60e4-5ed4-8e7f-b93408787455)

The only thing I knew about multiple sclerosis was that it was not a good illness to have. All I could think of was a poster I’d seen of a girl with her spine torn out and the legend ‘She wishes she could walk away from this picture too.’ Did that mean I wouldn’t be able to walk any more? That’s when I began to get upset. I couldn’t bear it if I ended up in a wheelchair.

I was in a complete state when I rang my best friend, Vera, a Viking from Oslo. ‘My life is over,’ I wailed. ‘Omar won’t want to go out with me any more. No man will. My friends won’t want to be my friends any more because I’ll be stuck at home and I won’t be able to go out. No one will want to know me. I’ll be useless.’ I must have sounded shrill and tearful.

Vera listened to my rant and then breathed deeply. I could feel her shifting her position to give the verbal equivalent of the slap you deliver to a hysterical woman.

‘You idiot! You can’t think very much of your friends if you think that. If I told you I had MS, would you stop being my friend?’

‘No, but—’

‘Well, how dare you even think I would stop being your friend just because you’ve got some disease! You wouldn’t abandon me, so why would I abandon you? Stop wallowing in it. Grow up and get on with your life!’

I felt myself start. The result was pretty much as if she had indeed delivered a heavy slap: the shock brought me back to reality. This wasn’t a romantic game, it was reality, and I was going to have to get used to it. I don’t like to admit it, but if things are out of my control I have a tendency towards self-pity. If anything was going to drive people away, it would be that, not the diagnosis. I rang a few of my more pragmatic friends to sound them out. I didn’t want people who would gush with sympathy. I wanted facts.

‘Don’t worry,’ one friend told me. ‘They’ve got a cure for it now.’ A drug called beta-interferon had been all over the news recently. ‘If you start taking it early enough, it’s got a really high success rate.’

How long had I had the disease, though? When had I first noticed my legs were getting weaker? Lots of memories flooded my brain. I thought back to when I was learning to waterski in Hong Kong in 1988, seven years earlier, and I hadn’t been able to stand up in the water. We’d tried over and over again, but I hadn’t been able to rise elegantly from the water, so I’d sat on a jetty and they’d towed me off from there. I remember feeling frustrated. Had that been an early symptom of MS, or was it just me being clumsy and impatient? (My MS has probably been unfairly blamed for many failings over the years, but if I’ve got to put up with the disease I may as well.)

I phoned other friends. Some told me they knew people with MS whose lives were barely affected. They still walked, held down jobs, had children and you’d never know they were ill except that they occasionally got a bit tired. That was comforting – that’s what I wanted to hear. I’d hoped it was a brain tumour because I’d imagined that, once treated, I’d get back to my normal self without any further repercussions, but I reckoned I could cope with a mild dose of MS that was controlled by taking this new miracle-drug, beta-interferon.

I phoned my old friend Mike. He was living in Vienna but happened to be in Paris, and he said, ‘Come out for the weekend. We’ll take your mind off things.’

We strolled along the Seine, stopping for coffee whenever my legs got tired and I started staggering. Passersby gave me scathing looks, thinking I was drunk, and I wondered if this was something I’d have to get used to.

‘Hello? Since when have you worried about what other people think?’ Mike teased.

In the evenings we went to piano bars and listened to chanteuses singing of unfaithful lovers and lost chances. It was good to be in another place, distracted from what was going to happen to me in the coming week, never mind the coming years. Mike had just broken up with his partner, the mother of his son, so we talked about that at length and didn’t dwell on my diagnosis. The only advice he gave me was about practical things, like making sure I had the insurance policy on my mortgage on my Bradford house sorted out before the diagnosis was official. Did I even have an insurance policy? I hadn’t a clue.

‘Are your savings in a high-interest, easy-access account?’ he asked.

‘What savings?’ Didn’t he know me at all? I wasn’t the kind of girl who had savings. I lived for today, spending every penny as I earned it and sometimes even before.

Still, I pretended to take note of all Mike’s nuggets of wisdom. It was good to focus on hard facts rather than speculate about the disease, and I was glad he was taking this approach and not smothering me in sympathy.

On Monday morning, after my weekend in Paris, I flew back into Gatwick Airport at 9 a.m. and jumped on a train straight to the hospital, only making it on time for my lumbar-puncture appointment because of the one-hour time difference between France and England.

The procedure was straightforward. I lay on my side on a hospital bed and curled up in a foetal position so that the doctor could stick a needle into my spine and extract some spinal fluid for testing. I was fine for the rest of the day, but the following morning I woke early feeling like I had the worst hangover of my life, with a God-awful, teeth-grinding headache that lasted for days. (I don’t object to a hangover if I deserve it, but this was just unfair.) Not everyone reacts like this to lumbar punctures, I hasten to add. More than 80 per cent of patients feel fine afterwards. Just my luck to be in the wrong percentage.

I made up a list of questions to take to my next appointment with the consultant a few days later and tried to compose myself. I wanted to come across as intelligent and able, the kind of person he would be glad to have as a patient. I wouldn’t break down or become hysterical; I’d be rational, logical and calm.

‘Are you absolutely sure it’s MS?’ I asked first, a germ of hope still lingering that he might have got it wrong. ‘Isn’t there anything else it could be?’

‘I could see the scleroses in your MRI and the lumbar puncture confirmed that it wasn’t anything else,’ he said.

‘What are “scleroses”?’ I hoped this wasn’t a dumb question.

‘Your central nervous system is like the wiring in your house. All electric cables have plastic round them to make sure that when you switch on an appliance the current just goes down the wire from the mains to the appliance. If you have a break in that plastic coating, the current leaks out and the appliance doesn’t work.’

I nodded. That made sense so far.

‘In the central nervous system the equivalent of the plastic surround is a fatty tissue called myelin. When there is damage to the myelin, it’s called a sclerosis. This disease is called multiple sclerosis because there are several places where the myelin has degenerated.’

‘How many?’

‘Different people have different degrees of the disease. If they just have a few small scleroses in unimportant areas, they might never notice any symptoms. If they have big scleroses in important areas, they will have more problems.’

‘Like not being able to walk?’

‘Like not being able to walk.’

I took a deep breath. ‘So what are my scleroses like?’

‘Not too bad. We’ll just have to wait and see how things progress.’

That was something. At least he hadn’t said, ‘Huge, gigantic, massive.’

‘I’ve heard about this drug beta-interferon. Should I start taking it straight away?’

‘I’m afraid you’re not a suitable candidate for beta-interferon,’ he said, dashing one of my pet hopes. ‘There’s a type of MS called relapsing-remitting and research suggests this drug may reduce the frequency of relapses, but I think you have another type called primary progressive. You’ve shown a pattern of mild but continuous symptoms, rather than severe episodes followed by periods of remission.’

‘Is that better?’ I wanted to ask, but didn’t. I had a feeling it wasn’t. I didn’t like the sound of the word ‘progressive’. Instead I asked, ‘What’s going to happen?’