По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

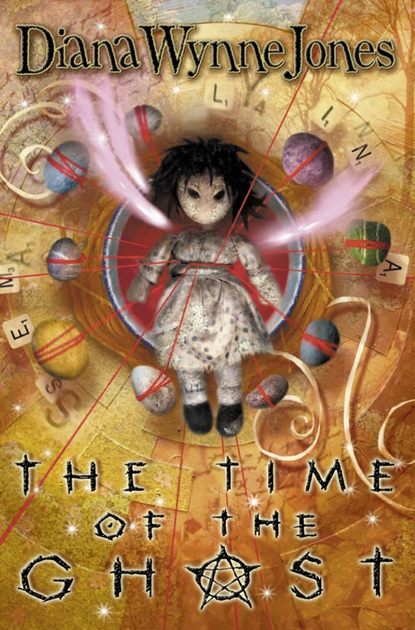

The Time of the Ghost

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Oh, all right.”

There were sounds of movement in the next room – sounds like a heavy creature with six legs. The creature came in about level with Sally’s head. It looked like two people under an old grey hearthrug.

It’s only Oliver, Sally told herself quickly. She found she had backed almost into the passage again. Seeing Oliver suddenly often had that effect on people. Oliver was probably an Irish wolfhound, but he was larger than a donkey, and blurred and misshapen all over. He looked like a bad drawing of a dog. And he was almost impossibly huge. Oliver wouldn’t hurt a fly, Sally told herself firmly.

Nevertheless, it was alarming the way Oliver shambled straight towards the passage door and Sally. His huge heavy-breathing head – more like a bear’s head or a wild boar’s – came level with Sally’s non-face and sniffed loudly. His shaggy clout of tail swung, once, twice. A distant whining came from somewhere in his huge throat. Then, even more distant, a rumbling grew inside his shaggy chest. He stepped backwards, still rumbling, and sideways, and his tail dropped and curled between his legs. He could not seem to take his great blurred eyes off the place where Sally was. The whine kept breaking out on the rumble and then giving way to a growl again.

“Whatever’s the matter with Oliver?” Charlotte said from the door of the living room.

Charlotte was just as much of a shock to Sally as Oliver had been. She was built on the same massive scale. Like Oliver, she was huge and blurred. Blurred fair hair stuck out round her head. A blurred face, like a poor photograph of angel Phyllis, floated in the hair. She was the size of a tall fat woman, and cased in a dress that had clearly been designed for a little girl. There was about her, blurred and vast, the feeling of a powerful personality which, like her lumping body, had somehow got itself cased in the mind of a little girl. She was carrying a book folded round one finger. “Oliver’s scared stiff!” she said.

“I know,” said Fenella. Oliver was trembling now, rattling the things on the table.

Nobody bothered with Oliver after that, because the door behind Sally crashed open. Sally was barged aside like a kite in a stiff wind, and Imogen stormed in.

“Mr Selwyn turned me out of the music rooms again!” Imogen yelled. “It’s impossible! How am I going to perfect my art? How shall I ever be famous like this?”

“You could win a screaming competition,” Fenella suggested. “Except that I’d beat you.”

“You little—” Imogen turned on Fenella, at a loss for words. “You Thing! And why are you wearing that green sack? It looks terrible!”

“I made her that green sack,” Charlotte said, advancing on Imogen and looming a little. And so she had, Sally remembered. Fenella’s clothes had been handed down three people before they reached Fenella, and they had all fallen to pieces. It was a pity, Sally thought, looking at the sack, that Cart was so very bad at sewing. It was not even a straight green sack. It puckered one side and drooped the other. The neck sort of looped over Fenella’s skinny chest.

Imogen realised her mistake and tried to apologise. “It was only an insult,” she explained, “chosen at random to express my feelings. I was thinking about my musical career.”

Which was typical Imogen, Sally thought, in the dim, remembering way she had been noticing everything so far. Imogen had set her heart on being a concert pianist. Very little else mattered to her. Sally looked at Imogen. Imogen, like Charlotte, was tall and fair, but, unlike Cart, Imogen was an unblurred version of Phyllis and very pretty indeed. This was unfair on Cart and Fenella, and unfair on Sally too, because Imogen was bigger and cleverer than Sally, and over a year younger.

What a hateful family I’ve got! Sally thought suddenly. Why did I come back here?

Oliver meanwhile, seeing that nobody noticed him, passed his great nose gently over the table. The butter was coaxed from under the newspaper, deftly magnetised, and slid away inside Oliver. This seemed to help Oliver get over the phenomenon of Sally a little. He advanced towards her, trembling a little, whining slightly, and gingerly swishing his tail.

“What is the matter with that dog?” said Imogen.

“We don’t know,” said Fenella.

All three of Sally’s sisters stared at her, and not one of them saw her.

(#ulink_021c2c72-b8df-5721-b4af-f48d8f65cf52)

Their name was Melford, Sally suddenly remembered. They were Charlotte, Selina, Imogen and Fenella Melford. But she still did not know what she was doing here in this state.

Perhaps I came back here to get revenged, she thought.

It was rather a horrible thought and one, Sally hoped, that would not have come to her in the ordinary way. But no one could deny that this was not the ordinary way. They were all three looking at her and she hated them all: big formless Cart in that babyish blue dress, and self-centred Imogen – it was a mark of Imogen’s character, it seemed to Sally, that Imogen had somehow got hold of a bright yellow trouser suit which would have fitted Cart better. On Imogen, it was so large that the top half hung in downward folds like a curtain, and the bottom half was in crosswise folds like two yellow concertinas. Imogen had great trouble in not treading on the ends of the trousers all the time. And she had evidently felt the suit needed brightening up. She was wearing mauve plastic beads and orange lipstick. As for Fenella, Sally thought angrily, she looked just like the little Thing Imogen had called her. Those knob-knees were like joints in the legs of insects, and for antennae she had those two knots of her hair.

I hate them so much I’ve come back to haunt them, Sally decided.

At that, the whirl of misty notions – which was all Sally’s nonexistent head seemed able to hold – took a sharp turn in the opposite direction and almost stopped. This is a dream after all, she told herself tremulously.

But was it? Where had Sally come back from, after all? She had no idea, except that there had been some kind of accident.

Oh good gracious, am I dead? Sally cried out. I’m not dead, am I? she asked her sisters.

It did no good. Unaware that anyone was asking them anything, they all went back to their own concerns. Then all at once it became very important to Sally that they should know she was there. It was even more important to her than the reason why she was here. She was sure at least one of them could explain everything, if only they knew she was here to be explained to.

Tenella! she shouted. Fenella, after all, had almost known she was there.

But Fenella climbed from the draining board, through the open window, and jumped down outside. Sally fluttered after her, towards the sink. Oliver followed, whining uneasily, but gave up with a huge sigh when Sally sailed away through the window after Fenella.

Fenella was walking this way and that through the orchard when Sally caught up with her. She seemed to be making sure nobody else was there.

There is someone, Sally said, coming to a halt in a clump of nettles in front of Fenella. Look! There’s me.

Fenella walked straight past her, frowning. Fenella’s frown was the one thing about her that was like Phyllis. It gave Fenella the angel look too – a fallen angel. “Weaving spiders come not near,” Fenella said to the air beyond Sally and walked on. She came to the hut made of old chairs and knelt down in front of the opening in the soggy carpet. At once, she became a large-fronted dwarf again, with spindly arms. The spindly arms stretched towards the hut. “Come forth, Monigan. Come forth and meet thy worshipper,” Fenella intoned. “Thy worshipper kneeleth here with both arms outstretched. Come forth! She never does come forth, you know,” she remarked to the air above Sally.

I know, Sally said impatiently. The Monigan game had gone on far too long, it seemed to her. She knew she had thought it was pretty boring when Cart first invented the Worship of Monigan a year ago. Fenella, listen, look! Notice me!

“Monigan, thou hast but one worshipper these days,” Fenella intoned, unheeding. “Thou hadst better look out, Monigan, or I shall go away too. Then where wouldst thou be? Come forth, I say to thee. Come forth!”

Fenella! Please! said Sally.

But Fenella simply swayed around on her knees, intoning. “Come forth! Monigan, thou mightst do me a favour and come forth just this once. Canst thou not understand how boring thou art, just sitting there? Come forth!”

It would teach you if she did! Sally said, unheard and soundless. Then she had an idea. If she could flip a latch and barge a door, she might be able to move something as light as a rag doll, if she tried very hard. Fenella would notice that at least. Sally drifted to the hut and ducked in through the old carpet.

She only had the part of her that seemed to be head and shoulders inside it, but even that was almost too much. It was dank and stifling in there. And it smelt. Sally had a moment’s wonder that she should mind a smell so much, when she seemed to have no real nose to smell with. But I can hear and see too, she thought. Mostly what I can’t do is feel. She could not feel the sopping carpet, though she could smell the mildew on it, and smell Monigan herself, leaning soggily against the table leg at the back of the hut. There was a sharp mushroom smell from the pale yellow grass. But the worst smell came from the four or five little dishes in front of Monigan. The stuff was too rotten for Sally to tell what it had once been, but it smelt worse than the school kitchen. In front of the dolls’ plates, someone had carefully planted three black feathers upright in the pale grass.

Hm, said Sally. I wonder if Fenella is the only worshipper. Or did she do that?

She leant further in to push Monigan. She did not want to in the least. Monigan was hideous. A year in the wet hut had turned the rag face livid grey, and fungus had puckered it until it looked like a maggot. The rest of Monigan was misshapen before she went into the hut. One time, Cart, Sally, Imogen and Fenella had each seized an arm or a leg – Sally could not remember whether it had been a quarrel or a silly game – and pulled until Monigan came to pieces. Then Cart, in terrible guilt, had sewed her together again, as badly as she had sewed Fenella’s green sack, and dressed her in a pink knitted doll’s dress. The dress was now maggot grey. To make it up to Monigan for being torn apart, Cart had invented the Worship of Monigan.

Sally did not like to go near Monigan, but she made one halfhearted attempt to push her. But she had forgotten how a rag doll, sitting in the wet, soaks up moisture like a sponge. Monigan was too heavy to move. Gladly, Sally came up out of the hut. It was unbearable in there.

“I shall go and check the hens now,” Fenella remarked to the air, as Sally emerged.

No – notice me first! Sally cried out.

Fenella simply unfolded her insect legs and went wandering off. “Spotted snakes with double tongue,” Sally heard her say. “I wonder, do goddesses know how boring they are?”

Sally left her to it and went to find Cart or Imogen. They were both in the living room. Sally drifted in there, with Oliver anxiously trudging behind her.

“Can’t you play this piano?” Cart was saying. She had one hand keeping her place in her book and the other vaguely pointing to the old upright piano against the wall.

Imogen and Sally both looked at the piano, Imogen with contempt, Sally as if she had never seen it before. It was a cheap, yellowish colour and very battered. Its yellow keys looked like bad teeth. Sally could see nobody ever used it because of the heaps of papers, books and magazines all over it. There was a box of paints on the bass end, with a paste pot full of painty water balanced crookedly among the black notes. A painting was propped on the yellow music-stand – a surprisingly good painting of Fenella standing in a blackberry bush. Sally wondered who had done it.

“Play that!” Imogen said contemptuously. “I’d rather play a xylophone compounded of dead men’s bones!” She collapsed her full yellow length on a dirty sofa, which gave off a loud twang of springs as she landed. “My career is in ruins,” she said. “Was Myra Hess ever tormented in this way? I think not.”

Why does she talk like a book all the time? Sally wondered irritably. Cart seemed busy with her reading again. Since there seemed little chance of either of them noticing her, Sally roosted dejectedly on the back of an armchair. Oliver, seeing her settled, flopped down himself with a deep groan and lay like a heaped up hearthrug. But he was not asleep. Every so often he whined and turned one morbid eye in Sally’s direction.