По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

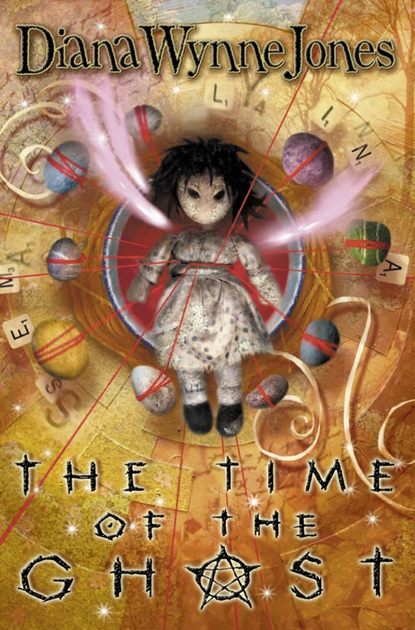

The Time of the Ghost

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“What’s wrong with him?” said Cart, looking up. Her blurry look was stronger when she was reading. It was as if she had faded into her book.

“His lunch, probably,” said Imogen. “You’re always fussing about that wretched animal.”

“Well, he’s my dog – or supposed to be,” said Cart. “I show a natural concern.”

“You show total, besotted devotion,” declared Imogen.

“I don’t! Why do you talk like a book all the time?” retorted Cart.

“It’s you that does that,” said Imogen. “You’re a walking dictionary.”

Cart went back to her book. Imogen stared stormily at the yellow piano. Sally tried to muster courage to attract their attention. She knew why she could not. They were both bigger than she was. Though why it should matter to me in this state, I can’t imagine, she said to herself.

Cart looked up again. “Isn’t it peaceful? I suppose it’s because the boys are in lessons. It’s hard on them breaking up a week after us, isn’t it?”

“No,” said Imogen. “I could use the music room if School term was over.”

“No you couldn’t,” said Cart. “Mrs Gill told me there’s a Course for Disturbed Children as soon as term ends. They’re coming to overrun the place on Tuesday.”

“Oh my Lord!” Imogen looked up at the ceiling and twiddled her mauve beads, faster and faster, so that they clattered viciously. “I hate the way we never get any holidays! It’s not fair!”

Oh, thought Sally. Her bodiless mind became clearer. Her parents kept a school – or rather, she seemed to think, they kept School House of a large boys’ boarding school. Yes, that was it. The girls went to quite a different school, some miles away. Oh dear! said Sally. She had been very silly looking for her class in the boys’ school. She was glad no one had known. Why had she not remembered she had broken up already? Because she had lived in the boys’ school all her life, she supposed, and it was much more real to her than her own. And Cart had supplied another memory: School was never empty. Almost as soon as the boys went home, more children came for courses. There were, as Imogen said, never any holidays.

Next second, Sally found herself jumping to attention. Her movement made Oliver raise his head and rumble unhappily. Cart said, “I feel really envious of Sally – a horrible yellow envy, like the colour of that piano. Why did we agree it should be her? Why Sally?”

“That’s why it’s so quiet, of course,” said Imogen.

“So it is!” said Cart, sitting forward as if Imogen had made a truly exciting discovery. “No whining and grumbling.”

“No arguing and quarrelling,” agreed Imogen, stretching as if she was suddenly very comfortable. “No stream of remarks about squalor. No tidying up.”

“No hysterics and crashing about,” said Cart. “No criticisms. I sometimes feel I could bear all the rest of Sally if she wasn’t always going on about the way we speak and walk and dress and so on.”

“The thing about her that really annoys me,” said Imogen, “is her beastly career, and the way she’s always on about it. She’s not the only one with a career to think of.”

There was a slight pause. “Well – no,” said Cart.

Sally looked from one to the other, wondering which she hated most. She had just decided it was Imogen, when Cart started again.

“No – it’s Sally’s pose of being good and sweet that drives me up the wall, now I think. And, if I venture the slightest criticism of Phyllis or Himself, she springs to their defence. She can’t seem to believe they’re not the most perfect parents anyone could have.”

Well, I think they are! Sally shouted. Neither of them heard her. Without question, it was Cart she hated most.

“That’s not quite fair, Cart,” Imogen said. She exuded justice and fair-mindedness. Sally remembered she always wanted to hit Imogen when she went like this. “Sally,” Imogen explained seriously, “truly does think this family is perfect. She loves her father and mother, Cart.”

Imogen’s saintly tone maddened Cart as well as Sally. Cart’s large face took on a blur of pink. Her eyes glared like holes in a mask. She roared, louder than Fenella, so that the windows buzzed, “Don’t you give me that nonsense!” and flung herself at Imogen. Oliver saw her coming just in time and lumbered to his feet to get out of the way. But Imogen, with the speed of long practice, catapulted off the sofa in front of him. Oliver was forced towards Sally, and he did not like that. He growled. But he also wagged his tail and lowered his head in Sally’s direction as he growled, because he could not understand what made her so peculiar.

Imogen and Cart took no notice. They dodged round Oliver, howling insults. And Sally forgot this was not the usual threesome quarrel and screamed unheard insults also. Talk about arguing and quarrelling! Talk about hysterics! And you can talk about careers, Imogen! How dare you criticise me behind my back!

“I think Oliver’s gone mad at last,” Fenella’s largest voice boomed behind them. Fenella was standing in the doorway, looking portentous.

Cart and Imogen – and Sally too – looked at the growling, wagging Oliver. “Well, he never did have any brain,” Imogen said.

“There really is something wrong with him, I think,” Cart said anxiously.

“I’ll tell you something else wrong,” said Fenella. “The black hen is still missing. I counted all the hens and looked everywhere. It’s gone.”

“There must be a fox,” said Cart. “I told you.”

“I didn’t mean that,” Fenella said meaningly.

“Then what did you mean?” said Cart.

Imogen said, “Cart, she’s tied her hair in knots. Look.”

Fenella dismissed this with magnificent scorn. “Of course Cart knows. It’s all part of the Plan.” Imogen, at this, looked surprisingly humble. “I meant the hen and Oliver.”

“You mean Oliver’s eaten it!” Cart exclaimed. She rushed to Oliver and tried anxiously to open his mouth. This was impossible. Oliver, as well as being very large, very strong and utterly thick, was also rather more obstinate than a donkey. He never did anything he did not want to, and he did not want his mouth open just then.

“I don’t think you’d be able to see the hen, even down Oliver,” Imogen objected.

“But he might have feathers on his teeth,” Cart gasped, wrenching at Oliver’s muzzle. It could have held two hens easily. “Think of the row there’ll be!”

“Then it’s better not to know,” said Imogen.

“If you’re ready to listen to me – I didn’t mean that,” Fenella said, and, still very portentous, she turned in a swirl of crooked green sack and marched away.

“Then what was it about?” Cart said to Imogen.

Imogen spread her hands. “Fenella being Fenella.” She raised her hands to the ceiling. “Oh why am I cursed with sisters?”

“You’re not the only one!” snarled Cart.

Sally left them beginning another quarrel and drifted miserably out into the orchard. The hens, like Oliver, seemed to know she was there. They were all gathered pecking at some corn near the gate, which Fenella must have put down so that she could count them, but they ran away chanking and squawking as Sally floated through the bars of the gate. Sally stared after their striding yellow legs and the brown sprays of tail-feathers jerking away from her in the grass. Silly things. But, as far as she could tell, the black one was indeed missing. She felt she ought to have known. She knew those hens as well as she knew her sisters.

That was the funny thing about being disembodied. Her mind did not seem to know anything properly until she was shown it. Drifting in and out among the trees, where hundreds of little pointed green apples lurked under the broad leaves, Sally tried to recall all the things she had been shown. Somewhere, surely, she must have been given a clue to what had made her like this – an inkling of what had happened at least. Well, she knew she lived in a school. She had three horrible sisters, who thought she was horrible too – or two of them did. Here, Sally broke off to argue passionately with the air.

I’m not like that! I’m not hysterical and I don’t go on about my career. I’m not like Imogen. They’re just seeing their own faults in me! And I don’t grumble and criticise. I’m ever so meek and lowly really – sort of gentle and dazed and puzzled about life. It’s just that I’ve got standards. And I do think Mother and Himself are perfect. I just know they are. So there!

But before all that started, hadn’t Cart shown that she and Imogen knew where Sally was supposed to be? They had. Cart had envied Sally – envied! That was rich! They were certainly not worried about her – but that proved nothing. Sally could not see either of those two worrying about anyone but themselves. But if Cart envied her, why should Sally have this feeling that there had been an accident? A mistake – something had gone wrong – there had been an accident—

Before Sally was aware, the balloon of panic had blown itself up inside her again. She whirled away on it, tumbling and rolling …

When at last it subsided, she found herself drifting along the paths of a slightly unkempt kitchen garden. She gave a shiver of guilt. This too was a forbidden place. There was, she remembered, a perfectly beastly gardener called Mr McLaggan, who hit you unpleasantly hard if he caught you, and shouted a lot whether he caught you or not. All the same, as she drifted past a hedge of gooseberry bushes, Sally had a firm impression that she and the others often came here, in spite of Mr McLaggan. Those same bushes, where a big red gooseberry or so still lingered among the white spines, had been raided when the gooseberries were apple green and not much larger than peas. And they had picked raspberries too, in a raid with the boys.

Sally saw Mr McLaggan down the end of a path, hoeing fiercely, and prudently drifted away through a brick wall. There was a wide green playing field on the other side of the wall. Very distantly, small white figures were engaged in the ceremony of cricket.

I think, Sally said uncertainly, I think I like watching cricket.